|

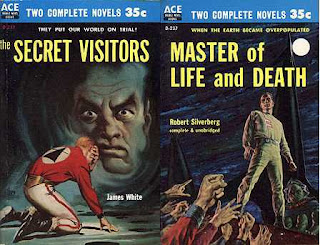

| (Covers by ? and Ed Emshwiller) |

The Secret Visitors is about 49,000 words long. It is James White's first novel. White also did a great deal of fanwriting, and he continued this throughout his life. I've read the samples collected in the NESFA book The White Papers, and he was a simply wonderful fan writer. He was also a fine pro writer. His career began with "Assisted Passage", in the January 1953 New Worlds. He was of course most famous for his long series of stories and novels about an interstellar hospital, Sector General, and as such he was noted for his aliens and their curious medical problems.

I've enjoyed a great deal of the work of both writers. Unfortunately, they were not yet fully developed at the time of writing these two novels, and neither story is really very good. The Silverberg novel is explicitly called "complete & unabridged" on the cover, which makes me wonder if there was another longer edition of the White novel. I can't find any evidence of an earlier edition, however. I see a later Ace edition by itself, a UK Digit edition, and a UK New English Library edition, on Abebooks. Some of the Abebooks listings call it a "Doctor Lockhart Adventure", leading me to wonder if there were sequels. Does anyone know?

One more point about Silverberg. I previously have listed particularly prolific Ace Double authors, but I have forgotten Silverberg. I could advance the excuse that he wrote many of his Doubles under pseudonyms (Calvin Knox most often, but also Ivar Jorgenson and David Osborne), but that's not the real reason. The real reason I didn't list him is that I forgot to think of him as an Ace Double author. But he was -- in his early, "hack", career. He wrote, as far as I can tell, 13 Ace Double halves, in 12 different books.

Master of Life and Death is an exemplar, it seems to me, of several features of SF of the 50s and 60s. For one thing, it is a strikingly didactic novel -- in this case on the subject of overpopulation. For another thing, it features what I believe is really the standard political future of SF of that period. This future, perhaps surprisingly, was not capitalist in nature, it was not (at least not overtly) America-dominated. Instead, the "default" state of world governance as of X years in the future (X could be 50 or 200 or 300), in 1960 or so, as described by SF, consisted of the United Nations in control, with a basically socialist (though rarely very detailed) economy. All this seems to me, in rereading many older stories, to be accepted all but without thought. That was simply the way things were going to be. There was nothing pro-Soviet about this -- indeed, if there was a backstory (there isn't in the book at hand) it might detail how wicked the Soviets were, until they were subsumed peacefully under the world government.

But economy, to be sure, isn't what Master of Life and Death is about. Though it must be said that the implied economic underpinning to this novel is naive and simplistic -- much like the political underpinning, and the scientific underpinning. It is, indeed, not a very good novel, hardly thought out at all. Though also told with a certain efficiency -- not exactly energy or verve, but efficiency, professionalism -- that makes it a fast read, and a book that holds the attention for the brief time it takes to read, if no longer.

The book is told in third-person but from the POV of Ray Walton, as the book opens the Assistant Administrator of the six-week-old Department of Population Equalization, or Popeek. The job of Popeek, in the horribly overpopulated world of 2232, is to balance population stresses. Reality Check #1 -- what is Silverberg's estimate of the horrible, insupportable, population level which we will have finally reached 275 years in the book's future? 7 billion. What is the current world population [as of my writing this review, 15 or so years ago], only 46 years in the book's future, according to the US Census Bureau? 6.3 billion. This doesn't invalidate the book, but it does speak to a certain failure of imagination. (I'm a bit cruel to him -- this failure of imagination was essentially universal at this time in the '50s.)

What does Popeek do, then? It moves people from overpopulated areas to sparsely populated areas. (Indeed, one of the first things we see Walton do is sign an order to move several thousand people from Belgium to Patagonia. The book doesn't consider the logistics of this.) Also, it arranges for unsuitable people to be euthanized -- babies with defects such as a potential to become tubercular, and old people who have become a burden on society. A familiar idea, but not really handled very well here. Anyway, Walton is confronted by a great poet, a favorite of Walton himself, who begs for the life of his young son. Walton secretly adjusts the records to save the boy's life, but his action is detected by his malcontent brother, whom Walton has given a job at Popeek. Now Walton is under his brother's thumb. Then an assassin kills Walton's boss, and Walton suddenly is in charge of all of Popeek.

He finds himself struggling with his own guilt, with his brother's threats, with internal problems in the department, and with three secret projects authorized by the former director: an immortality serum, terraformation of Venus, and FTL travel to allow colonization of nearby planets. The first is of course a disaster in an already overpopulated world. The second is apparently close to success -- but nothing has been heard from the planet Venus in, oh, a few days. The third is also close to success -- indeed, a ship has already been sent exploring! (Here though is another example of not thinking things through -- Silverberg details a plan to send ships to a potential habitable planet each carrying 1000 people, until a billion people have been moved. OK, suppose somehow ships can be built and launched at the rate of 1 per day -- how long would it take to move 1,000,000,000 people? Over 2700 years! Similar problems, really, would affect the use of Venus or any other "local" planet as a bleeder valve for excess population.)

Walton finds himself driven, in a ridiculously short time (the action of the book takes some 9 days) to absurdly evil actions to maintain his power, quash opposition, and push through the actions he feels necessary. It is ambiguous at times whether he is really after power or sincerely trying to do good. I felt for a while that Silverberg was trying for a tragic look at a good man corrupted. I felt for another while that he was trying for a satiric over the top look at an exaggerated regime of population control. But neither really comes off. And the book stumbles to a disappointing close, with "aliens ex machina" to solve some of the problems (though to be fair with a slightly unexpected ending twist).

Not a good book. The action is implausible, the general setup implausible, the science is dodgy, and the ending rushed and unsatisfactory.

The Secret Visitors also has serious problems, though in sum I enjoyed the story a bit more. It opens with Doctor John Lockhart, a WWII veteran, on a curious British Intelligence mission to prevent an upcoming war. His job is to identify when a mysterious old man is about to die, and to get to him in time for a last minute interrogation. When he does so, the man gibbers in an unknown language, and the Intelligence types seem rather eager to conclude that he is an alien. Before long there seem to be several factions of aliens to deal with, including a beautiful girl, several of these dying old men, and a crew at a hotel in Northern Ireland (not coincidentally, I'm sure, White's home).

The Intelligence people soon make there way to this hotel, and they learn that an evil alien travel agency is fomenting war on Earth in order that the planet, the most beautiful by far in the Galaxy (apparently because it is the only planet with axial tilt!), be maintained conveniently unspoiled for alien tourism. (It should be noted that the aliens generally seem to be fully human -- basically Spanish.) The beautiful girl is trying to smuggle evidence of this perfidy to the Galactic Court in order that the agency can be stopped. For this she needs the help of some humans -- and she seems particularly interested in the help of Lockhart. But is she telling the truth?

This setup is so extravagantly silly as to almost make the book impossible to continue with. And it isn't helped when White can't seem to decide if his method of interstellar travel involves time dilation or not (there's a man from two centuries in the past as a result of one space trip, but on the other hand this impending war seems possible to stop in short order via a round trip to the capitol planet and back.) And there is the absurd bit that Earth's medical science is so advanced compared to the aliens that Lockhart is treated almost like a god. (But the aliens have an immortality treatment -- that, it turns out, for unconvincing reasons, is WHY their medical science stinks.) And there's the part about Earth music being so superior that the aliens are reduced to tears of joy and admiration by an amateur harp player.

Still, there are good parts, such as the alien Grosni, who live partly in hyperspace. Lockhart, in a segment recalling White's Sector General series, must treat a sick Grosni. The story spirals outward from the beginning premise, leading to an action-packed but again not very convincing conclusion, with it must be said a fairly clever final resolution to the final battle. It's by no means a good novel, and I don't think it could possibly sell today, but it is in many places pleasant and imaginative entertainment.

I guess "Revolt on Alpha C" was generally considered a weak effort, but it is one of the brightest memories of my Golden Age. I bought it from the Scholastic Book Service in the fourth grade (age 10) with saved lunch money. It helped make me a fan. I also read "Master of Life and Death" a little later and liked it, too. But if I read them again today, my opinion would probably be the same as yours. Which is why I'm not going to. I treasure the memories.

ReplyDelete