Potential Hugo nominations for the 1958 Hugos (stories from 1957)

I made a post on Facebook about possible Hugo nominations for stories published in 1957 -- a year that was not well represented in Hugo history, due to the vagaries of changing Hugo eligibility rules, radically different Hugo categories from year to year, including no fiction Hugos in 1957, and a generally cavalier attitude towards the whole process. That post engendered a lot of productive comments, and I figured I'd make an updated version to preserve it on my blog. Thanks to Andrew Breitenbach, David Merrill, Gary Farber, Piet Nel, and Paul Fraser (among others) for suggestions for further stories, and for productive suggestions for more details about Hugo history.

Wandering through the history of the Hugos in the 1950s -- a chaotic time, with no well established rules, with constantly changing award categories, with a con committee, in one case, refusing to give fiction awards at all ... I realized that no stories from 1957 won a Hugo. (The 1958 Hugo for short story went to "Or All the Seas With Oysters", by Avram Davidson (Galaxy, May 1958) and the Hugo for -- get this -- "Novel or Novelette" went to "The Big Time", by Fritz Leiber, a novel (albeit very short) that was serialized in Galaxy, March and April 1958. In 1957, no Hugos for fiction were given.

I note as well that Richard A. Lupoff's excellent anthology What If?, Volume 1, selected "alternate Hugos" for the years 1952 through 1958, and his choice from 1957 was "The Mile-Long Spaceship", by Kate Wilhelm.

So, what the heck -- here's my list of proposed fiction nominees from 1957. In my first post for this year, before I had decided to extend the posts through the 1950s, I used the categories Novel, Novelette, and Short Story, and I only listed my five story nomination suggestion. I'm revising it so that for each year I am using the contemporary four short fiction categories, and adding mention of other possible nominees. That said, all the stories I listed in "Novelette" were actually novelettes ... though I mentioned "The Last Canticle" as a good candidate that I had passed over because it's part of A Canticle for Leibowitz.

Novel:

Citizen of the Galaxy, by Robert A. Heinlein

The Black Cloud, by Fred Hoyle

Wasp, by Eric Frank Russell

On the Beach, by Nevil Shute

The Midwich Cuckoos, by John Wyndham

Other possibilities:

Doomsday Morning, by C. L. Moore

Atlas Shrugged, by Ayn Rand

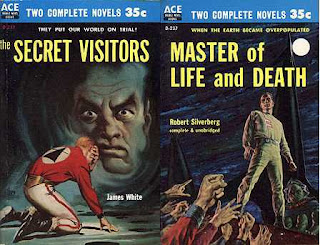

"The Dawning Light", by "Robert Randall" (Robert Silverberg and Randall Garrett)

I would vote for Citizen of the Galaxy among this selection.

Atlas Shrugged, it can be argued, is the most commercially successful, and most famous, SF novel of 1957. Doomsday Morning was C. L. Moore's last novel. The Silverberg/Garrett novel is pretty fun, if slight, the second of two they wrote for Astounding about the planet Nidor.

(By the way, The Naked Sun, by Isaac Asimov, is often cited as a 1957 novel, but its serialization in Astounding ended in December 1956. The same is true of Heinlein's The Door Into Summer, serialized in F&SF.)

Note that four of my suggested novel nominees (all except Heinlein) were born and raised in the UK (Shute moved to Australia in 1950.) Had this nomination list been real (unlikely) and had the Heinlein been replaced by Atlas Shrugged (even more unlikely) all five nominees would have been born and raised outside the US. (Rand immigrated from the Soviet Union at the age of 21.)

Novella:

"Profession", by Isaac Asimov (Astounding, July)

"The Night of Light", by Philip José Farmer (F&SF, June)

"The Last Canticle", by Walter M. Miller, Jr. (F&SF, February)

"The Lineman", by Walter M. Miller, Jr. (F&SF, August)

"Lone Star Planet", by H. Beam Piper and John J. McGuire (Fantastic Universe, March)

Other Possibilities:

"Get Out of my Sky", by James Blish (Astounding, January and February)

"Nuisance Value", by Eric Frank Russell (Astounding, January)

My vote in this category goes to Asimov's "Profession", really a quite strong novella. "The Last Canticle" would be the other possibility. If, as I assume, "The Night of Light" is the first version of Farmer's novel Night of Light -- it's the first version of perhaps Jimi Hendrix' favorite novel. As for "Get Out of my Sky", it's extremely frustrating. The first part is wonderful -- then Blish realized he was trying to sell to Campbell, and ruined it with an idiotic psi-based twist.

Novelette:

"Call Me Joe", by Poul Anderson (Astounding, April)

"The Queer Ones", by Leigh Brackett (Venture, March)

"Wilderness", by Zenna Henderson (F&SF, January)

"The Dying Man" aka "Dio", by Damon Knight (Infinity, September)

"Omnilingual", by H. Beam Piper (Astounding, February)

"It Opens the Sky", by Theodore Sturgeon (Venture, November)

Other possibilities:

"Brake", by Poul Anderson (Astounding, August)

"Ideas Die Hard", by Isaac Asimov (Galaxy, October)

"The Tunesmith", by Lloyd Biggle, Jr. (If, August)

"Nor Iron Bars", by James Blish (Infinity, November)

"All the Colors of the Rainbow", by Leigh Brackett (Venture, November)

"The Menace from Earth", by Robert A. Heinlein (F&SF, August)

A strong category, I think. My vote goes to "The Queer Ones", a fairly little known Brackett story, but very good.

Short Story:

"Hunting Machine", by Carol Emshwiller (Science Fiction Stories, May)

"Journeys End", by Poul Anderson (F&SF, February)

"The Men Return", by Jack Vance (Infinity, July)

"The Man Who Traveled in Elephants", by Robert A. Heinlein (Saturn, October)

"Manhole 69", by J. G. Ballard (New Worlds, November)

"Affair with a Green Monkey", by Theodore Sturgeon (Venture, May)

Other possibilities:

"Let's Be Frank", by Brian W. Aldiss (Science Fantasy, June)

"The Long Remembering", by Poul Anderson (F&SF, November)

"Build-Up" aka "The Concentration City", by J. G. Ballard (New Worlds, January)

"Forever Stenn" aka "The Ridge Around the World", by Algis Budrys (Satellite, December)

"The War is Over", by Algis Budrys (Astounding, February)

"Help! I am Dr. Morris Goldpepper", by Avram Davidson (Galaxy, July)

"Featherbed on Chlyntha", by Miriam Allen de Ford (Venture, November)

"The Lady Was a Tramp", by "Rose Sharon" (Judith Merril) (Venture, March)

"Mark Elf", by Cordwainer Smith (Paul M. A. Linebarger) (Saturn, May)

"Eithne", by "Idris Seabright" (Margaret St. Clair) (F&SF, July)

"Warm Man", by Robert Silverberg (F&SF, May)

"The Mile-Long Spaceship", by Kate Wilhelm (Astounding, April)

"The Men Return", is my choice among these short stories, one of my favorite shorter Vance stories. Of the less familiar stories here, I recommend a look at Walter Tevis' clever "The Ifth of Oofth", and Kate Wilhelm's first significant story, "The Mile-Long Spaceship". I also love, though it's kind of clunky, Algis Budrys' "The War is Over", which just wowed me when I read it as a teen.

I note, too, that the "Big Three" (Astounding, Galaxy, F&SF) are represented only by a novella, two novelettes and one short story among my "nominees". (And, to be fair, one novel.)

Other notes about 1958: it was the only year of the Hugos in which the winners did not get a rocket ship -- the award this year was a plaque. Also, 1958 was the last year in which there was not a codified process by which a fan vote selected a set of nominees, followed by a general vote for the Hugo.