The Creatures of Man, by Howard L. Myers

a review by Rich Horton

Is this book forgotten? Perhaps not -- it was only published in 2003. But the author was all but forgotten until his work was resurrected by Eric Flint and Guy Gordon. They have since pubished another collection, The Reign of Infinity, with his novel Cloud Chamber and a few more stories. Here's what I wrote back in 2003:

Eric Flint (often with the help of Guy Gordon) has been putting out a series for Baen books of collections of stories by older authors, now mostly forgotten. He began with a series of several books by James Schmitz, which when they get around to reissuing The Witches of Karres will have returned all of Schmitz's published stories to print. He has also put together collections by Randall Garrett, Christopher Anvil, Keith Laumer, Murray Leinster, and Tom Godwin. All these authors have long stopped writing, and all but Anvil (real name Harry Crosby) are dead. [Crosby (aka Anvil) died in 2009, after I wrote the first version of this.] All but Laumer were also primarily associated with Astounding/Analog and John W. Campbell. (Laumer published stories in Analog under Ben Bova's editorship, but I don't know of any he sold to Campbell.) (Well, Leinster was prolific enough that you couldn't say he was "primarily" associated with Astounding -- but he did publish a lot there.)

While I've found these collections to be of variable quality (I like the Schmitz books a lot, for instance, but the one Anvil book I read was rather poor), I do think the project as a whole is admirable. Flint has resurrected a lot of competent adventure-style SF of the 50s and 60s -- rarely great stuff but often quite enjoyable. I must admit, though, that I was surprised by his latest project -- a collection of stories by Howard L. Myers, also known as Verge Foray. I knew the name Foray as an Analog writer of the late 60s -- I didn't know the name Myers at all. I had an image of "Verge Foray" as the ultimate "late Campbell" writer. Offhand he didn't seem to me a writer much in need of resurrection. That said, I have to admit I'd read very little of his work -- a couple of Analog stories that seemed psi-obsessed to me, in line with one of Campbell's most annoying hobbyhorses.

So I picked up a copy of The Creatures of Man, ready to give Myers a fair try. This book includes 19 stories, a good portion of his total output. Another 5 or 10 stories and one novel (Cloud Chamber) exist. Myers was born in 1930, and published a story in Galaxy in 1952 ("The Reluctant Weapon" -- a pretty good piece, actually, one of the best in the book). He published nothing more until 1967, when "Lost Calling", as by "Verge Foray", appeared in Analog. He was quite prolific over the next few years, publishing a passel of stories in Analog as well as a few in Amazing, Fantastic, F&SF, If, and Galaxy. He died only 41 years of age in 1971. His stories kept appearing through 1974 -- his last, "The Frontliners", appeared in the July 1974 issue of Galaxy -- the issue just preceding the first one I ever saw. The novel did not come out until 1977. I can only assume that he left a pile of unsold stories which his mother (I'm guessing, but he seems to have been living with his mother when he died) kept marketing. All told, an interesting, and rather sad, career arc. Flint and Gordon assert that had he had the chance to continue developing, he'd have been a major author. I'm not so sure -- the later stories do not seem particularly to show an arc of improvement, though to be fair he may not have quite "finished" those that appeared after his death. I will say that he had some interesting ideas, though his prose was pedestrian, and his characters, especially the women, were totally unconvincing.

How was the book? It's a tale of two halves. The first half has some nice stuff. As I've mentioned, "The Reluctant Weapon", a story about a lazy superweapon abandoned by a long lost Galactic race, and its encounter with a backwoods Earthman, is a pretty fair effort. "Fit for a Dog" is a biting story of an ecologically challenged future earth and the evolved superdogs that inhabit it. "All Around the Universe" is not bad either, about a dilettantish man in the very far future, when the economy depends on "Admiration Points", and his search for a mysterious planet. It's both fairly witty and nicely imagined. And several more stories in the first half of the book betray a pretty fair SFnal imagination.

The second half of the book is devoted to a cycle of stories Flint has dubbed "The Chalice Cycle". Most of these are part of Myers' so-called "Econo-War" series, which began in Analog and concluded (long after his death) in Galaxy. These are set in a post-scarcity future in which two human federations of worlds are engaged in a mostly-nonviolent (with exceptions) "war". The idea is that even though people's needs are easily met, so ordinary competition for resources is unnecessary, people will stagnate without some sort of meaningful struggle -- hence, the "econo-war". The stories' setting reminded me (in a contrasting way) of Iain Banks's Culture, enough so to make me wonder if they weren't among the stories that Banks has said he was reacting to when he devised that setting. At any rate, Myers's take on things seems almost uber-Campbellian.

The various Econo-War stories involve the two sides in the War coming up with technological advances, giving first one side then the other a temporary advantage. There are some cute SFnal ideas involved, mainly the way people travel through space -- naked, with some implanted tech to provide protection, inertial suppression, and breathing, etc. However, I was mostly unconvinced -- I think one story in the setting would have been plenty -- the eventual 6 seemed tedious.

There are two pendant stories. One, "The Earth of Nenkumal", is more a "magic goes away" story -- it's a novella from Fantastic in 1974 that is set in the long past on Earth, when magic is being suppressed by the evil efforts of the "God-Warriors" -- a long period in which religion will take the place of magic, with concomitant misery, is forthcoming, and the hero, a repentant God-Warrior, is recruited to help one of the last magicians hide a powerful good luck charm for eventual use when magic returns. It's an OK story, with a decent twist at the end, but I was severely bothered by the sexual politics. It opens with a gang-bang on a table in a bog-standard fantasy pub -- fully consensual on the woman's part (she's a barmaid), but icky to me nonetheless. (The idea is that in the utopian magic world people are so unhungup about sex they just do it all the time, in public, with pretty much anyone.) It may be totally unfair of me to say this, but when you hear that the writer of such a scene was still living with his mother at age 41 you are hardly surprised. Towards the end the hero rapes a woman who soon after is grateful to him for having done so and asking for more. Ickier still, she is sexually mature but less than ten years old mentally. Perhaps I should have been speculating along with the author about such enlightened non-standard sexual mores, but I couldn't really play along.

The last story is "Questor", and it's about an Econo-War participant who lands on Earth looking for a fabled object which will give the holder good luck. Apparently this is the object hidden in "The Earth of Nenkumal", linking all those stories together. Well, OK, but I really think the link unnecessary and silly. However, "Questor" taken alone is actually a decent story, and interestingly it predates all the other "Econo-War" stories.

(Just to complain a bit more about Myers's sexual politics, the last Econo-War story features a mutated super girl who spends the story looking for a similarly mutated superman with whom to have kids. It wasn't actively offensive like the rape stuff in "The Earth of Nenkumal", but it was cringe-inducing in its portrayal of the woman's attitudes.)

So, in sum, I can't strongly recommend The Creatures of Man. It's an uneven book, with some OK stuff, some promising stories. Nothing I'd call a lost classic, but some pretty fine stuff. On the other hand, plenty of pedestrian stuff, and some downright icky stuff. I'm unconvinced by the editors' argument that Myers had the potential to be a top writer in the field, but I'll allow that if he could have developed his skills he had a decent imagination and he might have done some pretty good work.

Thursday, November 7, 2019

Birthday Review: Stories of Rahul Kanakia

Today is Rahul Kanakia's birthday. He's been publishing SF short fiction since 2006, and while I saw that story, "Butterfly Jesus Saves the World", in the second issue of an interesting small magazine, Fictitious Force, I confess I don't remember it. (Fictitious Force was also interesting for its unusual form factor -- very tall -- somewhat like Rahul, perhaps, though I haven't met him in person.) I started noticing his work early this decade, and the four reviews I present before are of stories that really impressed me, particularly "Empty Planets", one of the finest SF short stories of this decade, and to my mind a sadly underappreciated one. For the past few years he has been focussing on YA novels, it seems, with his first, Enter Title Here, having appeared in 2016, and his second, We Are Totally Normal, due in 2020.

Locus, December 2015

Lightspeed's November issue is a strong one. Rahul Kanakia's “Here is My Thinking on a Situation That Affects Us All” has one of the more original ideas I've seen in a while – not original as in mind-blowing or weird so much as in just taking an unexpected, and fairly logical, look at some some SF tropes from a slant angle. It's told by a spaceship that was buried in the Earth's core by aliens for millions of years, and which has finally emerged. It has a mission – for its makers – and it will not be deviated from it – at least, not much. The spaceship is effectively portrayed as truly non-human, and yet the story becomes something of a love story, though not in any expected way.

Locus, March 2016

Even better is Rahul Kanakia’s “Empty Planets” (Interzone, January-February), my pick for the best story in this young year. David is a child of a family of “shareholders” on the Moon far in the future. Most of his class use their economic heft either to earn procreation rights or to while away their lives in neurological loops, but he decides to pursue “Non Mandatory Studies”, even though the Machine that rules human society assures him he’s not smart enough to contribute anything special. There he meets another sort of outcast, Margery, a “recontactee” from a generation ship that the AI rescued. Margery is particularly intelligent, and she wants to study the potentially intelligent gas clouds of Altair III. David and Margery become close, and in a personal sense their lives follow a conventional story pattern. But nothing I’ve said even hints at the powerful, profound core of this story. The far future setting is pleasant but lonely – no other intelligent species has been found, the Machine seems to be shepherding humanity to extinction (in the gentlest way), and the only important question is “what does it all mean?” Which is, isn’t it, always the most important question? Achingly lovely, truly thought-provoking, sad but not sad. Kanakia has been doing nice work for some time, but this story seems a real milestone.

Locus, April 2018

Lightspeed’s February issue includes a fine and pointed fantasy by Rahul Kanakia, “A Coward’s Death”, about an all-powerful Emperor conscripting the first sons of his subjects to work on a massive statue. The moral is simple – his rule is unjust, but resistance, as they say, is futile. Nonetheless, one young man in the narrator’s village resists. The tale is lightly told but mordant, and effective.

Locus, June 2018

The 12 April issue of Beneath Ceaseless Skies includes a nice piece from Rahul Kanakia, “Weft”, told by a magic user named Thread, who with his two companions is charged with hunting down people who have gained potentially dangerous magical powers and eliminating them. The current subject is a cook’s daughter, and the question arises, what has she done to deserve extermination? Why not let her go? But can they get away with that? And is it really a good idea? All interestingly posed questions.

Locus, December 2015

Lightspeed's November issue is a strong one. Rahul Kanakia's “Here is My Thinking on a Situation That Affects Us All” has one of the more original ideas I've seen in a while – not original as in mind-blowing or weird so much as in just taking an unexpected, and fairly logical, look at some some SF tropes from a slant angle. It's told by a spaceship that was buried in the Earth's core by aliens for millions of years, and which has finally emerged. It has a mission – for its makers – and it will not be deviated from it – at least, not much. The spaceship is effectively portrayed as truly non-human, and yet the story becomes something of a love story, though not in any expected way.

Locus, March 2016

Even better is Rahul Kanakia’s “Empty Planets” (Interzone, January-February), my pick for the best story in this young year. David is a child of a family of “shareholders” on the Moon far in the future. Most of his class use their economic heft either to earn procreation rights or to while away their lives in neurological loops, but he decides to pursue “Non Mandatory Studies”, even though the Machine that rules human society assures him he’s not smart enough to contribute anything special. There he meets another sort of outcast, Margery, a “recontactee” from a generation ship that the AI rescued. Margery is particularly intelligent, and she wants to study the potentially intelligent gas clouds of Altair III. David and Margery become close, and in a personal sense their lives follow a conventional story pattern. But nothing I’ve said even hints at the powerful, profound core of this story. The far future setting is pleasant but lonely – no other intelligent species has been found, the Machine seems to be shepherding humanity to extinction (in the gentlest way), and the only important question is “what does it all mean?” Which is, isn’t it, always the most important question? Achingly lovely, truly thought-provoking, sad but not sad. Kanakia has been doing nice work for some time, but this story seems a real milestone.

Locus, April 2018

Lightspeed’s February issue includes a fine and pointed fantasy by Rahul Kanakia, “A Coward’s Death”, about an all-powerful Emperor conscripting the first sons of his subjects to work on a massive statue. The moral is simple – his rule is unjust, but resistance, as they say, is futile. Nonetheless, one young man in the narrator’s village resists. The tale is lightly told but mordant, and effective.

Locus, June 2018

The 12 April issue of Beneath Ceaseless Skies includes a nice piece from Rahul Kanakia, “Weft”, told by a magic user named Thread, who with his two companions is charged with hunting down people who have gained potentially dangerous magical powers and eliminating them. The current subject is a cook’s daughter, and the question arises, what has she done to deserve extermination? Why not let her go? But can they get away with that? And is it really a good idea? All interestingly posed questions.

Thursday, October 31, 2019

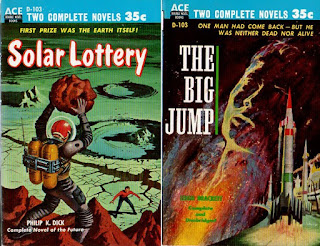

Ace Double Reviews, 115: Solar Lottery, by Philip K. Dick/The Big Jump, by Leigh Brackett

Ace Double Reviews, 115: Solar Lottery, by Philip K. Dick/The Big Jump, by Leigh Brackett (#D-103, 1955, 35 cents)

a review by Rich Horton

I bought a copy of this Ace Double for a surprisingly good price -- Philip Dick's work often costs more than I'm happy paying. I have different editions of both books, but this seemed like a book worth having. So I'm assembling an Ace Double review from my previous reviews of these novels independently.

It is a pretty significant book for an Ace Double -- two major writers, each of who would surely have been a Grand Master had they not died too soon. Each have writing credits on major SF movies, Dick of course for the original novel behind Blade Runner (and for quite a few other films of varying quality), and Brackett for the first version of the screenplay of The Empire Strikes Back. They are very different writers, but each very important in their own way.

Solar Lottery was Philip Dick's first novel, and this 1955 Ace Double was its first edition. (There was a UK hardcover a year later retitled World of Chance.) It seems to be reasonably well regarded but I must say I found it a mess. It's set in a future in which the leader of the Solar System is chosen by lottery. The current leader, Quizmaster Verrick, has held the position for 10 years, even though assassins are selected by lot to try to kill him. Most of society is controlled by corporations that rate people, theoretically according to their abilities. People swear allegiance to individuals or corporations. As the novel opens, Ted Benteley is at last able to legally escape his allegiance to his corporation, and he travels to Batavia (now Djakarta, of course) in Indonesia, seat of the government, to try to work for the Quizmaster. Unbeknownst to him, however, a new Quizmaster has just been selected, an "unclassified" named Leon Cartwright. Benteley is fooled into swearing direct allegiance to the old Quizmaster.

Cartwright has long been a Prestonite, devotee of the mad theories of John Preston, who believed in a tenth planet beyond Pluto called Flame Disc. Cartwright has just supervised the launch of a spaceship intended to reach Flame Disc, and his only hope of his new Quizmaster position is to buy time for the ship to reach Flame Disc before Solar authorities stop it. As soon as he becomes Quizmaster, Verrick sets in place a plan to fix the lottery for the assassin, and to use a remote controlled android as the next assassin. This, along with a clever scheme to sequentially control the android with different people, will allow his assassin to evade the telepathic protectors of the Quizmaster.

So it's kind of a wild, uncontrolled, mix of elements, some clever, some interesting, some just loony. The plot sort of reels along, as Ted is shanghaied to being one of the assassin's controllers, and also as he fools around with an ex-telepath girl now working for Verrick, while his true destiny, natch, is to work with Cartwright and become the next Quizmaster, hopefully in so doing restoring sanity to Earth's government. Everywhere traces of Dick's impressive imagination, as well as various of his obsessions, are clear -- but nowhere do things cohere, nowhere to they make even the weird sense that Dick made in his better novels.

The Big Jump was first published in the February 1953 issue of Space Stories, and this Ace Double was its first book publication. It is some 42,000 words, and I believe the book and magazine versions are essentially the same. It's a curious sort of book, spending much of its length in Brackett's "hard-boiled" mode, and for that portion its not very successful. But right toward the end it effectively switches to her high-romantic mode, and that brief portion is rather nice.

Arch Comyn is a spaceship construction worker. He hears that somebody has completed "the Big Jump" -- travelled to another star. He learns that his close friend Paul Rogers was on the crew. However, details about the expedition have been suppressed. Comyn hears a rumor that the survivors are hidden in a hospital on Mars owned by the Cochrane Company (which built the spaceship involved). Comyn makes his way to Mars and rather implausibly barges into the Cochrane complex, and finds the hospital room with the one survivor, Captain Ballantyne. Ballantyne is dying, but Comyn hears him say just a bit -- a hint about "transuranics". Then Ballantyne dies, and Comyn is in the custody of the Cochrane Company, who try to beat his secret out of him. Eventually they let him go, and he heads back to Earth, concerned that the secret of what Ballantyne found on a planet of Barnard's Star will be of altogether too much interest to several parties. And indeed, Comyn detects a tail -- but then he sees Cochrane heiress Sydna Cochrane on TV, making a toast to Ballantyne and hinting that a visit from Comyn would be welcome.

Soon Comyn is confronting Sydna, though not before shaking two separate tails, one of whom tries to kill him. Sydna, who is 100% pure Lauren Bacall (remember, this is Brackett in her "tough guy thriller" mode), convinces Comyn to follow her to the Cochrane complex on Luna. Once there, Comyn to his horror sees what's left of Ballantyne -- even though he is dead, his body somehow still lives mindlessly. Before long, he is a) having an affair with Sydna, and b) pushing to join the second expedition to Barnard's Star. After some more hijinks (another assassination attempt), Comyn and a few Cochranes (and some redshirts) are on their way to Barnard's Star. One of the "Cochranes" is William Stanley, a weaselly cousin-by-marriage who lusts after Sydna despite his married state. Stanley reveals that he has stolen the lost logs of the Ballantyne expedition, and he uses this vital knowledge to negotiate controlling interest in the prospective Transuranic company.

Then they arrive at Barnard's Star, and the novel changes tone entirely, to something transcendental, much more reminiscent of the best of Brackett's planetary romances. The other members of the first expedition are found, living in a primitive state with the presumptive natives of the planet. (Natives who seem to be fully humanoid for no reason at all!) Comyn finds his friend Paul Rogers, who refuses to return to Earth. It seems that beings called the Transuranae, composed of transuranic elements, have conferred immortality and freedom from conflict and want on the inhabitants of this planet. So once again we confront the choice -- intellect, striving, knowledge vs. bliss and contentment. (Cf. countless other SF stories, such as "The Milk of Paradise" by Tiptree.) It's no surprise what Comyn chooses (or has chosen for him), but Brackett presents the alternatives in her most evocative style, and really this final section is quite effective.

It's not one of Brackett's best works, but in the end it's decent stuff. The first part, however, is full of plot holes and implausibilities. As well as plain silly stuff like the horror everyone feels at seeing the quasi-living Ballantyne -- still twitching after his death. Spooky, maybe, but not the stuff of Lovecraftian horror as Brackett would have us believe.

a review by Rich Horton

|

| (Covers by Ed Valigursky and Robert E. Schulz) |

It is a pretty significant book for an Ace Double -- two major writers, each of who would surely have been a Grand Master had they not died too soon. Each have writing credits on major SF movies, Dick of course for the original novel behind Blade Runner (and for quite a few other films of varying quality), and Brackett for the first version of the screenplay of The Empire Strikes Back. They are very different writers, but each very important in their own way.

Solar Lottery was Philip Dick's first novel, and this 1955 Ace Double was its first edition. (There was a UK hardcover a year later retitled World of Chance.) It seems to be reasonably well regarded but I must say I found it a mess. It's set in a future in which the leader of the Solar System is chosen by lottery. The current leader, Quizmaster Verrick, has held the position for 10 years, even though assassins are selected by lot to try to kill him. Most of society is controlled by corporations that rate people, theoretically according to their abilities. People swear allegiance to individuals or corporations. As the novel opens, Ted Benteley is at last able to legally escape his allegiance to his corporation, and he travels to Batavia (now Djakarta, of course) in Indonesia, seat of the government, to try to work for the Quizmaster. Unbeknownst to him, however, a new Quizmaster has just been selected, an "unclassified" named Leon Cartwright. Benteley is fooled into swearing direct allegiance to the old Quizmaster.

Cartwright has long been a Prestonite, devotee of the mad theories of John Preston, who believed in a tenth planet beyond Pluto called Flame Disc. Cartwright has just supervised the launch of a spaceship intended to reach Flame Disc, and his only hope of his new Quizmaster position is to buy time for the ship to reach Flame Disc before Solar authorities stop it. As soon as he becomes Quizmaster, Verrick sets in place a plan to fix the lottery for the assassin, and to use a remote controlled android as the next assassin. This, along with a clever scheme to sequentially control the android with different people, will allow his assassin to evade the telepathic protectors of the Quizmaster.

So it's kind of a wild, uncontrolled, mix of elements, some clever, some interesting, some just loony. The plot sort of reels along, as Ted is shanghaied to being one of the assassin's controllers, and also as he fools around with an ex-telepath girl now working for Verrick, while his true destiny, natch, is to work with Cartwright and become the next Quizmaster, hopefully in so doing restoring sanity to Earth's government. Everywhere traces of Dick's impressive imagination, as well as various of his obsessions, are clear -- but nowhere do things cohere, nowhere to they make even the weird sense that Dick made in his better novels.

The Big Jump was first published in the February 1953 issue of Space Stories, and this Ace Double was its first book publication. It is some 42,000 words, and I believe the book and magazine versions are essentially the same. It's a curious sort of book, spending much of its length in Brackett's "hard-boiled" mode, and for that portion its not very successful. But right toward the end it effectively switches to her high-romantic mode, and that brief portion is rather nice.

Arch Comyn is a spaceship construction worker. He hears that somebody has completed "the Big Jump" -- travelled to another star. He learns that his close friend Paul Rogers was on the crew. However, details about the expedition have been suppressed. Comyn hears a rumor that the survivors are hidden in a hospital on Mars owned by the Cochrane Company (which built the spaceship involved). Comyn makes his way to Mars and rather implausibly barges into the Cochrane complex, and finds the hospital room with the one survivor, Captain Ballantyne. Ballantyne is dying, but Comyn hears him say just a bit -- a hint about "transuranics". Then Ballantyne dies, and Comyn is in the custody of the Cochrane Company, who try to beat his secret out of him. Eventually they let him go, and he heads back to Earth, concerned that the secret of what Ballantyne found on a planet of Barnard's Star will be of altogether too much interest to several parties. And indeed, Comyn detects a tail -- but then he sees Cochrane heiress Sydna Cochrane on TV, making a toast to Ballantyne and hinting that a visit from Comyn would be welcome.

Soon Comyn is confronting Sydna, though not before shaking two separate tails, one of whom tries to kill him. Sydna, who is 100% pure Lauren Bacall (remember, this is Brackett in her "tough guy thriller" mode), convinces Comyn to follow her to the Cochrane complex on Luna. Once there, Comyn to his horror sees what's left of Ballantyne -- even though he is dead, his body somehow still lives mindlessly. Before long, he is a) having an affair with Sydna, and b) pushing to join the second expedition to Barnard's Star. After some more hijinks (another assassination attempt), Comyn and a few Cochranes (and some redshirts) are on their way to Barnard's Star. One of the "Cochranes" is William Stanley, a weaselly cousin-by-marriage who lusts after Sydna despite his married state. Stanley reveals that he has stolen the lost logs of the Ballantyne expedition, and he uses this vital knowledge to negotiate controlling interest in the prospective Transuranic company.

Then they arrive at Barnard's Star, and the novel changes tone entirely, to something transcendental, much more reminiscent of the best of Brackett's planetary romances. The other members of the first expedition are found, living in a primitive state with the presumptive natives of the planet. (Natives who seem to be fully humanoid for no reason at all!) Comyn finds his friend Paul Rogers, who refuses to return to Earth. It seems that beings called the Transuranae, composed of transuranic elements, have conferred immortality and freedom from conflict and want on the inhabitants of this planet. So once again we confront the choice -- intellect, striving, knowledge vs. bliss and contentment. (Cf. countless other SF stories, such as "The Milk of Paradise" by Tiptree.) It's no surprise what Comyn chooses (or has chosen for him), but Brackett presents the alternatives in her most evocative style, and really this final section is quite effective.

It's not one of Brackett's best works, but in the end it's decent stuff. The first part, however, is full of plot holes and implausibilities. As well as plain silly stuff like the horror everyone feels at seeing the quasi-living Ballantyne -- still twitching after his death. Spooky, maybe, but not the stuff of Lovecraftian horror as Brackett would have us believe.

Saturday, October 26, 2019

In Memoriam, Michael Blumlein

Rudy Rucker has reported that Michael Blumlein has died, aged 71. I didn't know Blumlein, though I reprinted his exceptional 2012 story "Twenty-Two and You" in The Year's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy: 2013 Edition. But I have been intrigued by his work since discovering his 1986 story, "The Brains of Rats". (We reprinted "The Brains of Rats" at Lightspeed here.) So I will memorialize him in the way I have: by remembering his stories, via things I've written about them, for Locus and for my pre-Locus SFF Net newsgroup.

Also, he has a new novel, or long novella, out this year from Tor.com. It's called Longer, and I missed it earlier but will get it it now.

F&SF Summary, 2000

"Fidelity: a Primer" (September) just struck me as charming and somehow "true". I really liked it. I think as things stand now it's my favorite novelette of the year,

And the following, from a discussion about the definition of SF:

[Gordon van Gelder here brings up "Fidelity: a Primer", a Michael Blumlein F&SF story from 2000, one of my favorite stories of that year. The story is at best only barely SF (I thought is was, but I agree that you could read it differently). But, Gordon suggests, it is important to the success of the story that the reader suspect that it might turn out to be SF. I.e., the venue affects reader expectations, and thus affects the typical reading of the story, possibly in important ways. Interesting, though I admit to being made uneasy by the implication that "Fidelity: a Primer" would be a lesser story if published in the New Yorker.]

2001 Recommended Reading

And Michael Blumlein's "Know How, Can Do" (F&SF, December) combines some clever wordplay -- clever but also thematically meaningful -- with a quite original story about a real scientific idea with real consequences, and real, if decidedly odd, characters facing loss.

Locus, July 2008

The cover story for F&SF in July is a novella from the always interesting Michael Blumlein. “The Roberts” concerns a brilliant architect whose workaholic ways lay waste to his love life. He hits upon a creepy solution – designing his own lover – but this too has pitfalls. It’s a nice story, but a bit too obvious in its working out, and it lacks the shocking originality that characterizes Blumlein’s best work.

Flurb Summary, 2008

My favorite story was Michael Blumlein's "The Big One" (#6), only barely fantastical, indeed almost Carveresque at times, about four men who knew each other in high school fishing much later in life, with lots of, well, life issues impending.

Locus, March 2012

Also first-rate is “Twenty-Two and You”, by Michael Blumlein (F&SF, March-April), which quite plausibly addresses the idea of genetic fixes for inherited diseases. Here a young couple wants to have children, but family history suggests that pregnancy might be very risky for the wife. So she has her genome sequenced, and learns the bad news. But it is possible in this near future to change your genome … but the genome is a complicated thing. This is a nice example of a story with no villains, indeed no fools, but still sadness. An excellent piece of pure science fiction in the sense that it closely examines the effects of scientific change on real people.

Locus, January 2014

Just one magazine to cover this month, the last F&SF of 2013. The longest story is “Success”, by Michael Blumlein, one of our most interesting and original writers. Alas, this story, about a brilliant scientist who goes, it seems mad, never really came to life for me. Dr. Jim, the central character, is cured, after a fashion, and marries again, a long-suffering woman, also an academic. He is working on his life's work, a book about the gene, the epigene, and the paragene, while she is pursuing tenure in a more ordinary fashion. Dr. Jim also battles something, or someone, mysterious in the basement, and becomes obsessed with building something in the backyard, to his wife's eventual disgust … leading to a reversal of fortunes, perhaps … Blumlein is never uninteresting, but as I aid, here he doesn't really – forgive me – succeed.

Also, he has a new novel, or long novella, out this year from Tor.com. It's called Longer, and I missed it earlier but will get it it now.

F&SF Summary, 2000

"Fidelity: a Primer" (September) just struck me as charming and somehow "true". I really liked it. I think as things stand now it's my favorite novelette of the year,

And the following, from a discussion about the definition of SF:

[Gordon van Gelder here brings up "Fidelity: a Primer", a Michael Blumlein F&SF story from 2000, one of my favorite stories of that year. The story is at best only barely SF (I thought is was, but I agree that you could read it differently). But, Gordon suggests, it is important to the success of the story that the reader suspect that it might turn out to be SF. I.e., the venue affects reader expectations, and thus affects the typical reading of the story, possibly in important ways. Interesting, though I admit to being made uneasy by the implication that "Fidelity: a Primer" would be a lesser story if published in the New Yorker.]

2001 Recommended Reading

And Michael Blumlein's "Know How, Can Do" (F&SF, December) combines some clever wordplay -- clever but also thematically meaningful -- with a quite original story about a real scientific idea with real consequences, and real, if decidedly odd, characters facing loss.

Locus, July 2008

The cover story for F&SF in July is a novella from the always interesting Michael Blumlein. “The Roberts” concerns a brilliant architect whose workaholic ways lay waste to his love life. He hits upon a creepy solution – designing his own lover – but this too has pitfalls. It’s a nice story, but a bit too obvious in its working out, and it lacks the shocking originality that characterizes Blumlein’s best work.

Flurb Summary, 2008

My favorite story was Michael Blumlein's "The Big One" (#6), only barely fantastical, indeed almost Carveresque at times, about four men who knew each other in high school fishing much later in life, with lots of, well, life issues impending.

Locus, March 2012

Also first-rate is “Twenty-Two and You”, by Michael Blumlein (F&SF, March-April), which quite plausibly addresses the idea of genetic fixes for inherited diseases. Here a young couple wants to have children, but family history suggests that pregnancy might be very risky for the wife. So she has her genome sequenced, and learns the bad news. But it is possible in this near future to change your genome … but the genome is a complicated thing. This is a nice example of a story with no villains, indeed no fools, but still sadness. An excellent piece of pure science fiction in the sense that it closely examines the effects of scientific change on real people.

Locus, January 2014

Just one magazine to cover this month, the last F&SF of 2013. The longest story is “Success”, by Michael Blumlein, one of our most interesting and original writers. Alas, this story, about a brilliant scientist who goes, it seems mad, never really came to life for me. Dr. Jim, the central character, is cured, after a fashion, and marries again, a long-suffering woman, also an academic. He is working on his life's work, a book about the gene, the epigene, and the paragene, while she is pursuing tenure in a more ordinary fashion. Dr. Jim also battles something, or someone, mysterious in the basement, and becomes obsessed with building something in the backyard, to his wife's eventual disgust … leading to a reversal of fortunes, perhaps … Blumlein is never uninteresting, but as I aid, here he doesn't really – forgive me – succeed.

Thursday, October 24, 2019

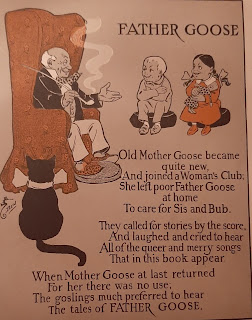

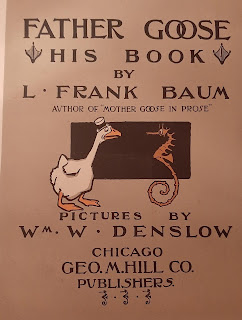

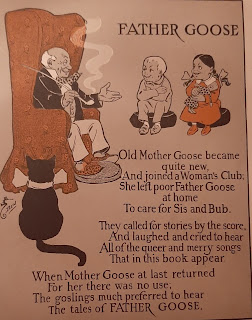

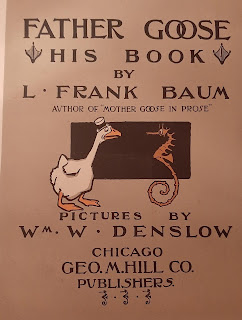

Old Bestseller: Father Goose: His Book, by L. Frank Baum

Old Besteller: Father Goose: His Book, by L. Frank Baum, illustrated by W. W. Denslow

a review by Rich Horton

I found this book at an estate sale, and it looked intriguing. Turns out nice copies are very valuable. My copy isn't exactly nice, but it's in tolerable shape for a book from 1899. It was definitely a bestseller, a major one, I think. My copy was the third printing, 15000 copies, in November 1899. The first edition (September 1899) was 5700 copies, the second, in October, was 10,000 copies.

You all know Lyman Frank Baum, I trust. He was born in 1856 and died in 1919. His early adult life was financially rather a mess, with a series of not terribly successful ventures in poultry breeding, acting, and sales. He moved from New York to South Dakota (which became, more or less, the Kansas of The Wizard of Oz) then to Chicago. While in Chicago he published a children's book called Mother Goose in Prose (1897), illustrated by Maxwell Parrish(!), that was fairly successful. This led to the book at hand, Father Goose, which was the bestselling children's book of 1899. And in 1900 he published The Wizard of Oz, and we know where that went! (Though, despite its enormous success, Baum's financial incompetence, and his grandiose theatrical plans, led to later money problems.) W. W. Denslow, the illustrator of Father Goose, also illustrated (and shared copyright in) the first couple of Oz books, which led to a nasty breakup when they quarreled over credit.

Baum, anyway, eventually found his way to California. He wrote about 16 Oz books and several other fantasies. He was involved in multiple musical productions of Oz related work, and some plays, and early movies, often to his financial detriment. He also reputedly designed parts of the Hotel Del Coronado, on an island near San Diego. After his death, other authors, most notably Ruth Plumly Thompson, continued the Oz series.

(For what it's worth -- fairly little -- I worked with a guy name Francis Baum for a while a number of years ago. He seemed nonplussed by allusions to Oz.)

As for Father Goose: His Book? Well, what it purports to be is "modern" verses in the style of the Mother Goose rhymes. Is it successful? To my ears, not really. The poems seem mostly a bit labored, and the conceits not terribly interesting. Part of the problem is some horribly racist bits -- the piece about the n-word boy is all but impossible to read today, and the stories about Chinamen and the Irish aren't much better. But if we ascribe those to not exactly hostile, just insensitive, views of the time the book was written, still, the poems just aren't much fun. That's not entirely fair -- one in three, maybe, are kind of cute. But never, really, lasting. The Mother Goose rhymes endure -- and deservedly so. And these are forgotten -- deservedly so too, I'd say.

As for Father Goose: His Book? Well, what it purports to be is "modern" verses in the style of the Mother Goose rhymes. Is it successful? To my ears, not really. The poems seem mostly a bit labored, and the conceits not terribly interesting. Part of the problem is some horribly racist bits -- the piece about the n-word boy is all but impossible to read today, and the stories about Chinamen and the Irish aren't much better. But if we ascribe those to not exactly hostile, just insensitive, views of the time the book was written, still, the poems just aren't much fun. That's not entirely fair -- one in three, maybe, are kind of cute. But never, really, lasting. The Mother Goose rhymes endure -- and deservedly so. And these are forgotten -- deservedly so too, I'd say.

(But for all that, The Wizard of Oz is remembered, and absolutely deservedly so!)

Finally, I must mention the pictures, by W. W. Denslow. And these really are quite nice. As noted above, the original Oz illustrations were also by Denslow, and they are very fine as well. Finally, I should mention that this book is hand-lettered, quite well, by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

Finally, I must mention the pictures, by W. W. Denslow. And these really are quite nice. As noted above, the original Oz illustrations were also by Denslow, and they are very fine as well. Finally, I should mention that this book is hand-lettered, quite well, by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

a review by Rich Horton

I found this book at an estate sale, and it looked intriguing. Turns out nice copies are very valuable. My copy isn't exactly nice, but it's in tolerable shape for a book from 1899. It was definitely a bestseller, a major one, I think. My copy was the third printing, 15000 copies, in November 1899. The first edition (September 1899) was 5700 copies, the second, in October, was 10,000 copies.

You all know Lyman Frank Baum, I trust. He was born in 1856 and died in 1919. His early adult life was financially rather a mess, with a series of not terribly successful ventures in poultry breeding, acting, and sales. He moved from New York to South Dakota (which became, more or less, the Kansas of The Wizard of Oz) then to Chicago. While in Chicago he published a children's book called Mother Goose in Prose (1897), illustrated by Maxwell Parrish(!), that was fairly successful. This led to the book at hand, Father Goose, which was the bestselling children's book of 1899. And in 1900 he published The Wizard of Oz, and we know where that went! (Though, despite its enormous success, Baum's financial incompetence, and his grandiose theatrical plans, led to later money problems.) W. W. Denslow, the illustrator of Father Goose, also illustrated (and shared copyright in) the first couple of Oz books, which led to a nasty breakup when they quarreled over credit.

Baum, anyway, eventually found his way to California. He wrote about 16 Oz books and several other fantasies. He was involved in multiple musical productions of Oz related work, and some plays, and early movies, often to his financial detriment. He also reputedly designed parts of the Hotel Del Coronado, on an island near San Diego. After his death, other authors, most notably Ruth Plumly Thompson, continued the Oz series.

(For what it's worth -- fairly little -- I worked with a guy name Francis Baum for a while a number of years ago. He seemed nonplussed by allusions to Oz.)

As for Father Goose: His Book? Well, what it purports to be is "modern" verses in the style of the Mother Goose rhymes. Is it successful? To my ears, not really. The poems seem mostly a bit labored, and the conceits not terribly interesting. Part of the problem is some horribly racist bits -- the piece about the n-word boy is all but impossible to read today, and the stories about Chinamen and the Irish aren't much better. But if we ascribe those to not exactly hostile, just insensitive, views of the time the book was written, still, the poems just aren't much fun. That's not entirely fair -- one in three, maybe, are kind of cute. But never, really, lasting. The Mother Goose rhymes endure -- and deservedly so. And these are forgotten -- deservedly so too, I'd say.

As for Father Goose: His Book? Well, what it purports to be is "modern" verses in the style of the Mother Goose rhymes. Is it successful? To my ears, not really. The poems seem mostly a bit labored, and the conceits not terribly interesting. Part of the problem is some horribly racist bits -- the piece about the n-word boy is all but impossible to read today, and the stories about Chinamen and the Irish aren't much better. But if we ascribe those to not exactly hostile, just insensitive, views of the time the book was written, still, the poems just aren't much fun. That's not entirely fair -- one in three, maybe, are kind of cute. But never, really, lasting. The Mother Goose rhymes endure -- and deservedly so. And these are forgotten -- deservedly so too, I'd say.(But for all that, The Wizard of Oz is remembered, and absolutely deservedly so!)

Finally, I must mention the pictures, by W. W. Denslow. And these really are quite nice. As noted above, the original Oz illustrations were also by Denslow, and they are very fine as well. Finally, I should mention that this book is hand-lettered, quite well, by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

Finally, I must mention the pictures, by W. W. Denslow. And these really are quite nice. As noted above, the original Oz illustrations were also by Denslow, and they are very fine as well. Finally, I should mention that this book is hand-lettered, quite well, by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.Friday, October 18, 2019

Birthday Review: Short Fiction of Charles Stross

Charlie Stross turns 55 today (damn kids!), so it's a good time for a look at his short fiction!

Locus, February 2002

Asimov's also features the latest of Charles Stross' stories about Manfred Macx, genius information entrepreneur in a frenetic near-Singularity future. In "Tourists", Manfred's enhanced glasses, and attached memory, are stolen, and he finds himself essentially unable to cope. Fortunately, his lover Annette and his AI cat Aineko are soon on his track, and there is a chance for a solution, involving alien tourists, lobsters, and avatars of a dead man. I don't think this is the best of Stross' Macx stories -- perhaps the idea density which has been so impressive throughout the series is losing some impact -- but it is another solid outing by one of the most impressive of Britain's "Radical Hard SF" clade.

Locus, June 2002

The latest of Charles Stross's Manfred Macx stories is "Halo" (Asimov's, June), stepping forward a generation to focus on Manfred's daughter, Amber. Amber has sold herself into slavery to herself, in order to escape the clutches of her mother, Manfred's villainous ex-wife, the IRS agent Pamela. But Mom finds a way to get at Amber even in the Jupiter system. How can Amber deal with this latest threat? As with earlier Macx stories, the real meat is in the tossed-off details of life as we approach a Vingean singularity, and in the clever touch Stross displays in describing his high-tech future and its economics – such as an asteroid taking on the personality of Barney ("I love you, you love me, it's the law of gravity …"). Beyond the jokes and tech Stross has a bigger story to tell in this series, and "Halo" advances the overall arc an intriguing bit.

Locus, October 2002

The other novella, perhaps even stronger, is the latest and to date longest of Charles Stross' Manfred Macx stories, "Router" (Asimov's, October). Manfred's daughter Amber, the Queen of the Ring Imperium (a monarchy located around Jupiter), has sent virtual copies of herself and her court on a lightsail-propelled ship to a brown dwarf. She and her people hope to find a router there for interstellar communication (based on information they have gleaned from the "lobsters" of the very first story in the series). She is also dealing with another lawsuit from her estranged mother – luckily the local laws of her monarchy apply, including trial by combat. And back home in the inner Solar System, humanity is close to a Vingean singularity. This story, as with all of Stross' recent stories, is just brimming with, put most simply, Very Cool Ideas, and it also still manages to have likeable characters, a clever and involving plot, and an intriguing resolution opening up nicely to the next story in the sequence. (How Stross will keep upping the ante as the series continues, though, I surely don't know!)

Locus, January 2003

The December offering from Sci Fiction begs comparison with "Junk DNA", if only because both stories are collaborations by writers noted for madcap near future extrapolation. "Jury Service", by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow, concerns a man who is selected to serve on a "jury" evaluating, for safety and utility, some tech downloaded from post-singularity, all the while worrying about a bio-hazard that seems to have infected him. The plot is twisty and interesting and frenetic, and the heart of the story, the depiction of wacky future tech and social adjustments to that tech, is neat stuff.

Locus, December 2003

The December Asimov's features two more novellas. Charles Stross's "Curator" is the latest in his Accelerando series, following Manfred Macx and his descendants as humanity goes through a Vingean Singularity. This story introduces Manfred's grandson Sirhan. Sirhan is waiting for his "mother" Amber to return from her trip to the Router, an alien installation at another star. He plans to claim all her assets as child support, even though he is really the child of another, now dead, version of Amber. Manfred's long-estranged first wife has her own plans for her family. While of course Aineko the cat has other ideas. It's more of the same fascinating stuff as the earlier stories in the series, but it doesn't work quite as well. I think this is because this story seems more a transition, more part of an eventual novel, less self-contained. Still, the wit and audacious inventiveness that we expect from Stross remain.

Locus, February 2004

DAW's "monthly magazine" of themed anthologies offers a reliable if seldom exciting source of new SF and Fantasy. 2003 closes with Mike Resnick's New Voices in Science Fiction: 20 short stories by new writers (variably defined: from complete unknowns like Paul Crilley to well-established writers like Kage Baker and Susan R. Mathews). For the most part the stories seem more promising than outstanding. A high point is Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross's "Flowers From Alice", a very clever story of posthuman marriage with a delightful ending twist.

Locus, August 2004

I mentioned Emswhiller's story from the second issue of Argosy, dated May-June. I think the magazine is successfully straddling genres according to its apparent ambition. Besides the Emshwiller story there is a fine mystery by O'Neil DeNoux, a nice humorous Lucifer Jones piece from Mike Resnick, and a very enjoyable wild pair of novellas from Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross. Their 2002 Sci Fiction novella "Jury Service" is reprinted, followed by a brand new story, "Appeals Court", that follows directly from the first. Our hero, Huw, carrying an Ambassador from the post-Singularity "Cloud" of uploaded intelligences, makes his way willy-nilly to a much-changed U.S. There he finds primitive Baptists, petroleum trees, a hypercolony of flesh-eating ants, and another Church promoting lots of sex. And he hasn't escaped Judge Judy either ... Like the first story, it's full of whipcrack smart satire and wild speculation – fun stuff.

Locus, October 2004

With Charles Stross, still often called a "hot new writer" though he has been publishing almost as long as McHugh, we can segue neatly from September to October-November at Asimov's, as these issues see the final two stories of his acclaimed Accelerando sequence. "Elector" (second to last) is set on Saturn, where the remnants of relatively normal humanity, including a number of resurrected people based on historical figures, live in an artificial habitat. Amber Macx believes that the "Vile Offspring", humankind's descendants, running on "computronium" in the inner System, will soon destroy Saturn, so she is running for office, with a platform advocating escape on a starship. Sirhan, for whom Amber is an "eigenmother" (his mother was another version of Amber), regards her candidacy with some suspicion, especially as he suspects her of throwing a loose woman, Rita, at him. Manfred Macx, reincarnated, shows up as well. The final story is "Survivor", set decades later in a new human system built around a brown dwarf, using hacked alien "Router" technology. Sirhan and Rita have a son, Manni, who has some secrets of his own, which become significant when the artificial cat Aineko returns, wanting to close a long ago bargain. Both stories are enjoyable, though I think I liked "Survivor" more. "Elector" is denser with ideas but thin as a story – "Survivor", with the advantage of being the last in the series, comes to some real, and interesting, conclusions about Galactic society and the pitfalls of the Singularity.

Locus, April 2006

Probably best of all in One Million A. D. is Charles Stross’s “Missile Gap”, which at first blush seems to violate the anthology’s guidelines: it is set in roughly the present day, though on a rather altered Earth. But not to worry! At any rate this Earth is sufficiently weird to hold one’s interest no matter how far in the future the story is set! It seems to have been moved, as of 1962, to an enormous disk, with escape velocity such that space travel is impossible. But the Cold War continues, sort of. The story follows an American effort to colonize a dangerous new continent, and a Soviet effort to explore the disk using an Ekranoplane – a very large seaplane. Disturbing discoveries are made by both groups, which might lead to more understanding of what has happened to Earth. But a third thread follows a shadowy spy, who it turns out has quite a different agenda to pursue, one with rather stark implications for humanity as a whole.

Locus, May 2006

Indeed Stross and Wolfe provide two of the better stories in Baen's Universe's first issue. Stross’s “Pimpf” is a short novelette about the Laundry, the secret agency at the heart of his novel The Atrocity Archive. In this case Bob Howard has to deal with a new employee getting lost in a computer game, as well as menacing Human Resources types.

Locus, December 2006

Oh look – it’s 2007 already! At any rate, here is the January 2007 Asimov’s. The cover story is a very fun outing from Charles Stross called “Trunk and Disorderly”, a new entry in the shortish list of stories about “Elephants in Spaaace!” The elephant this time is a pet dwarf mammoth foisted on the narrator, Ralph, by his sister. Ralph is a member of the Dangerous Drop Club, and he is planning a drop from orbit to the surface of Mars. So he is not at all pleased to have to deal with a mammoth – especially after his sex-robot has just left him, and as he tries to break in a new butler. The whole confection is, as might seem clear, a bit Wodehousian, with SFnal interest supplied by details such as various semi-mechanical characters, and by the new political organization of the Solar System which includes, for instance, an Emirate of Mars, and by plenty of Stross’s slick offhanded incluing of future brainstem kicks. The plot is breakneck enough, involving a scheme to overturn the Emir, but plot hardly matters here – what matters is the fun we have getting to the end.

Locus, February 2010

Story collections often have good new stories as well. Indeed, often novellas, as with Charles Stross’s Wireless, an excellent collection throughout, that closes with a brilliant time travel novella, “Palimpsest”. Pierce is recruited from something like our time by agents of the Stasis, an organization a bit like Asimov’s Eternity, devoted to preserving Earth and humanity across time and until the end of time. Stross extrapolates dizzyingly from this concept, showing us multiple histories of humanity, and multiple futures for the Solar System (and indeed Galaxy), and clever and chilling means of enforcement of Stasis, and inevitably the other side, the opponents. Pierce is given a real life (or lives) with emotional weight, and real decisions to make. The Asimov reference is purposeful – I have no doubt Stross had The End of Eternity in mind when writing this story – but the story is its own.

Locus, February 2002

Asimov's also features the latest of Charles Stross' stories about Manfred Macx, genius information entrepreneur in a frenetic near-Singularity future. In "Tourists", Manfred's enhanced glasses, and attached memory, are stolen, and he finds himself essentially unable to cope. Fortunately, his lover Annette and his AI cat Aineko are soon on his track, and there is a chance for a solution, involving alien tourists, lobsters, and avatars of a dead man. I don't think this is the best of Stross' Macx stories -- perhaps the idea density which has been so impressive throughout the series is losing some impact -- but it is another solid outing by one of the most impressive of Britain's "Radical Hard SF" clade.

Locus, June 2002

The latest of Charles Stross's Manfred Macx stories is "Halo" (Asimov's, June), stepping forward a generation to focus on Manfred's daughter, Amber. Amber has sold herself into slavery to herself, in order to escape the clutches of her mother, Manfred's villainous ex-wife, the IRS agent Pamela. But Mom finds a way to get at Amber even in the Jupiter system. How can Amber deal with this latest threat? As with earlier Macx stories, the real meat is in the tossed-off details of life as we approach a Vingean singularity, and in the clever touch Stross displays in describing his high-tech future and its economics – such as an asteroid taking on the personality of Barney ("I love you, you love me, it's the law of gravity …"). Beyond the jokes and tech Stross has a bigger story to tell in this series, and "Halo" advances the overall arc an intriguing bit.

Locus, October 2002

The other novella, perhaps even stronger, is the latest and to date longest of Charles Stross' Manfred Macx stories, "Router" (Asimov's, October). Manfred's daughter Amber, the Queen of the Ring Imperium (a monarchy located around Jupiter), has sent virtual copies of herself and her court on a lightsail-propelled ship to a brown dwarf. She and her people hope to find a router there for interstellar communication (based on information they have gleaned from the "lobsters" of the very first story in the series). She is also dealing with another lawsuit from her estranged mother – luckily the local laws of her monarchy apply, including trial by combat. And back home in the inner Solar System, humanity is close to a Vingean singularity. This story, as with all of Stross' recent stories, is just brimming with, put most simply, Very Cool Ideas, and it also still manages to have likeable characters, a clever and involving plot, and an intriguing resolution opening up nicely to the next story in the sequence. (How Stross will keep upping the ante as the series continues, though, I surely don't know!)

Locus, January 2003

The December offering from Sci Fiction begs comparison with "Junk DNA", if only because both stories are collaborations by writers noted for madcap near future extrapolation. "Jury Service", by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow, concerns a man who is selected to serve on a "jury" evaluating, for safety and utility, some tech downloaded from post-singularity, all the while worrying about a bio-hazard that seems to have infected him. The plot is twisty and interesting and frenetic, and the heart of the story, the depiction of wacky future tech and social adjustments to that tech, is neat stuff.

Locus, December 2003

The December Asimov's features two more novellas. Charles Stross's "Curator" is the latest in his Accelerando series, following Manfred Macx and his descendants as humanity goes through a Vingean Singularity. This story introduces Manfred's grandson Sirhan. Sirhan is waiting for his "mother" Amber to return from her trip to the Router, an alien installation at another star. He plans to claim all her assets as child support, even though he is really the child of another, now dead, version of Amber. Manfred's long-estranged first wife has her own plans for her family. While of course Aineko the cat has other ideas. It's more of the same fascinating stuff as the earlier stories in the series, but it doesn't work quite as well. I think this is because this story seems more a transition, more part of an eventual novel, less self-contained. Still, the wit and audacious inventiveness that we expect from Stross remain.

Locus, February 2004

DAW's "monthly magazine" of themed anthologies offers a reliable if seldom exciting source of new SF and Fantasy. 2003 closes with Mike Resnick's New Voices in Science Fiction: 20 short stories by new writers (variably defined: from complete unknowns like Paul Crilley to well-established writers like Kage Baker and Susan R. Mathews). For the most part the stories seem more promising than outstanding. A high point is Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross's "Flowers From Alice", a very clever story of posthuman marriage with a delightful ending twist.

Locus, August 2004

I mentioned Emswhiller's story from the second issue of Argosy, dated May-June. I think the magazine is successfully straddling genres according to its apparent ambition. Besides the Emshwiller story there is a fine mystery by O'Neil DeNoux, a nice humorous Lucifer Jones piece from Mike Resnick, and a very enjoyable wild pair of novellas from Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross. Their 2002 Sci Fiction novella "Jury Service" is reprinted, followed by a brand new story, "Appeals Court", that follows directly from the first. Our hero, Huw, carrying an Ambassador from the post-Singularity "Cloud" of uploaded intelligences, makes his way willy-nilly to a much-changed U.S. There he finds primitive Baptists, petroleum trees, a hypercolony of flesh-eating ants, and another Church promoting lots of sex. And he hasn't escaped Judge Judy either ... Like the first story, it's full of whipcrack smart satire and wild speculation – fun stuff.

Locus, October 2004

With Charles Stross, still often called a "hot new writer" though he has been publishing almost as long as McHugh, we can segue neatly from September to October-November at Asimov's, as these issues see the final two stories of his acclaimed Accelerando sequence. "Elector" (second to last) is set on Saturn, where the remnants of relatively normal humanity, including a number of resurrected people based on historical figures, live in an artificial habitat. Amber Macx believes that the "Vile Offspring", humankind's descendants, running on "computronium" in the inner System, will soon destroy Saturn, so she is running for office, with a platform advocating escape on a starship. Sirhan, for whom Amber is an "eigenmother" (his mother was another version of Amber), regards her candidacy with some suspicion, especially as he suspects her of throwing a loose woman, Rita, at him. Manfred Macx, reincarnated, shows up as well. The final story is "Survivor", set decades later in a new human system built around a brown dwarf, using hacked alien "Router" technology. Sirhan and Rita have a son, Manni, who has some secrets of his own, which become significant when the artificial cat Aineko returns, wanting to close a long ago bargain. Both stories are enjoyable, though I think I liked "Survivor" more. "Elector" is denser with ideas but thin as a story – "Survivor", with the advantage of being the last in the series, comes to some real, and interesting, conclusions about Galactic society and the pitfalls of the Singularity.

Locus, April 2006

Probably best of all in One Million A. D. is Charles Stross’s “Missile Gap”, which at first blush seems to violate the anthology’s guidelines: it is set in roughly the present day, though on a rather altered Earth. But not to worry! At any rate this Earth is sufficiently weird to hold one’s interest no matter how far in the future the story is set! It seems to have been moved, as of 1962, to an enormous disk, with escape velocity such that space travel is impossible. But the Cold War continues, sort of. The story follows an American effort to colonize a dangerous new continent, and a Soviet effort to explore the disk using an Ekranoplane – a very large seaplane. Disturbing discoveries are made by both groups, which might lead to more understanding of what has happened to Earth. But a third thread follows a shadowy spy, who it turns out has quite a different agenda to pursue, one with rather stark implications for humanity as a whole.

Locus, May 2006

Indeed Stross and Wolfe provide two of the better stories in Baen's Universe's first issue. Stross’s “Pimpf” is a short novelette about the Laundry, the secret agency at the heart of his novel The Atrocity Archive. In this case Bob Howard has to deal with a new employee getting lost in a computer game, as well as menacing Human Resources types.

Locus, December 2006

Oh look – it’s 2007 already! At any rate, here is the January 2007 Asimov’s. The cover story is a very fun outing from Charles Stross called “Trunk and Disorderly”, a new entry in the shortish list of stories about “Elephants in Spaaace!” The elephant this time is a pet dwarf mammoth foisted on the narrator, Ralph, by his sister. Ralph is a member of the Dangerous Drop Club, and he is planning a drop from orbit to the surface of Mars. So he is not at all pleased to have to deal with a mammoth – especially after his sex-robot has just left him, and as he tries to break in a new butler. The whole confection is, as might seem clear, a bit Wodehousian, with SFnal interest supplied by details such as various semi-mechanical characters, and by the new political organization of the Solar System which includes, for instance, an Emirate of Mars, and by plenty of Stross’s slick offhanded incluing of future brainstem kicks. The plot is breakneck enough, involving a scheme to overturn the Emir, but plot hardly matters here – what matters is the fun we have getting to the end.

Locus, February 2010

Story collections often have good new stories as well. Indeed, often novellas, as with Charles Stross’s Wireless, an excellent collection throughout, that closes with a brilliant time travel novella, “Palimpsest”. Pierce is recruited from something like our time by agents of the Stasis, an organization a bit like Asimov’s Eternity, devoted to preserving Earth and humanity across time and until the end of time. Stross extrapolates dizzyingly from this concept, showing us multiple histories of humanity, and multiple futures for the Solar System (and indeed Galaxy), and clever and chilling means of enforcement of Stasis, and inevitably the other side, the opponents. Pierce is given a real life (or lives) with emotional weight, and real decisions to make. The Asimov reference is purposeful – I have no doubt Stross had The End of Eternity in mind when writing this story – but the story is its own.

Birthday Review: Iron Sunrise, by Charles Stross

Today is Charles Stross's birthday. I plan to put together a look at his short fiction later, but for the morning, how about this review of one of his early novels.

Iron Sunrise is a sequel to Charles Stross's 2003 novel Singularity Sky. Sequel isn't a precise term here -- Singularity Sky resolved its story quite well, and this novel is set in the same universe and features the two main characters of the previous novel in important roles, but the main conflict is completely new. Stross wrote one other novelette in this universe ("Bear Trap"), and he now declares himself finished. It's an interesting setup, and could certainly profitably be mined for further stories, but he seems to feel it has become a bit shopworn, and a bit outdated. Anyway, he has a fecund imagination, and his other ongoing work (The Atrocity Archives, Accelerando, The Family Trade) certainly shows that he will not lack for interesting settings.

Iron Sunrise is a sequel to Charles Stross's 2003 novel Singularity Sky. Sequel isn't a precise term here -- Singularity Sky resolved its story quite well, and this novel is set in the same universe and features the two main characters of the previous novel in important roles, but the main conflict is completely new. Stross wrote one other novelette in this universe ("Bear Trap"), and he now declares himself finished. It's an interesting setup, and could certainly profitably be mined for further stories, but he seems to feel it has become a bit shopworn, and a bit outdated. Anyway, he has a fecund imagination, and his other ongoing work (The Atrocity Archives, Accelerando, The Family Trade) certainly shows that he will not lack for interesting settings.

I was tempted, when I first wrote this, to defer entirely to Charles Oberndorf's review in a recent New York Review of Science Fiction. Oberndorf, it seemed to me, captured the strengths and weaknesses of the book very well. So I recommend you read it if you can -- but I'll do something quick here as well.

The story opens as "a nondescript McWorld named Moscow" is dying -- its sun having been detonated by some enemy. They immediately blame a rival world, New Dresden, and automatic defenses launch a reprisal. But is New Dresden really to blame? And even if they are, is there any point to destroying yet another system?

One of the refugees fleeing the effects of the Moscow disaster is a teenager named Victoria Strowger, who calls herself Wednesday. Guided by her imaginary friend, she tracks down a mysterious piece of information on her home station before leaving. Her friend is named Herman -- which reveals to any reader of Singularity Sky that "he" is in fact an agent of the Eschaton, a post-singularity intelligence which aims to protect its existence by severely prohibiting certain atrocities and especially causality violations. Even in her new home, Wednesday realizes that she is a target -- for reasons she doesn't really understand. So she escapes on a ship heading to -- New Dresden.

A variety of other people are also involved. The coming attack on New Dresden is something the UN wishes to prevent, and the agent assigned to the problem is Rachel Mansour, heroine of Singularity Sky. She and her husband Martin Springfield end up on the same ship with Wednesday. So does a veteran political blogger named Frank. And so too are representatives of a vile group of Nazis-in-Space(tm). It appears this last group may have something to do with the problems at both Moscow and New Dresden. They are determined enemies of the Eschaton. And they have a special interest in Wednesday, and whatever she may have learned ...

It's a fast moving and fun story, with plenty of pretty neat ideas. It's a bit more smoothly written than Singularity Sky. It resolves intelligently and fairly satisfyingly -- perhaps there is just a hint of the over-convenient about the conclusion. Oberndorf's review also points out, quite sensibly, that Stross's imagination, so fecund at times, fails him at other times. One way is that all his worlds seem pretty bland (though this is actually explained by the terraforming action of the Eschaton). Another problem is the way Wednesday is portrayed -- as a pretty typical disaffected 90s goth girl, to a first approximation. In sum -- a good book, one of the better SF novels of the year, but no more than good.

Iron Sunrise is a sequel to Charles Stross's 2003 novel Singularity Sky. Sequel isn't a precise term here -- Singularity Sky resolved its story quite well, and this novel is set in the same universe and features the two main characters of the previous novel in important roles, but the main conflict is completely new. Stross wrote one other novelette in this universe ("Bear Trap"), and he now declares himself finished. It's an interesting setup, and could certainly profitably be mined for further stories, but he seems to feel it has become a bit shopworn, and a bit outdated. Anyway, he has a fecund imagination, and his other ongoing work (The Atrocity Archives, Accelerando, The Family Trade) certainly shows that he will not lack for interesting settings.

Iron Sunrise is a sequel to Charles Stross's 2003 novel Singularity Sky. Sequel isn't a precise term here -- Singularity Sky resolved its story quite well, and this novel is set in the same universe and features the two main characters of the previous novel in important roles, but the main conflict is completely new. Stross wrote one other novelette in this universe ("Bear Trap"), and he now declares himself finished. It's an interesting setup, and could certainly profitably be mined for further stories, but he seems to feel it has become a bit shopworn, and a bit outdated. Anyway, he has a fecund imagination, and his other ongoing work (The Atrocity Archives, Accelerando, The Family Trade) certainly shows that he will not lack for interesting settings.I was tempted, when I first wrote this, to defer entirely to Charles Oberndorf's review in a recent New York Review of Science Fiction. Oberndorf, it seemed to me, captured the strengths and weaknesses of the book very well. So I recommend you read it if you can -- but I'll do something quick here as well.

The story opens as "a nondescript McWorld named Moscow" is dying -- its sun having been detonated by some enemy. They immediately blame a rival world, New Dresden, and automatic defenses launch a reprisal. But is New Dresden really to blame? And even if they are, is there any point to destroying yet another system?

One of the refugees fleeing the effects of the Moscow disaster is a teenager named Victoria Strowger, who calls herself Wednesday. Guided by her imaginary friend, she tracks down a mysterious piece of information on her home station before leaving. Her friend is named Herman -- which reveals to any reader of Singularity Sky that "he" is in fact an agent of the Eschaton, a post-singularity intelligence which aims to protect its existence by severely prohibiting certain atrocities and especially causality violations. Even in her new home, Wednesday realizes that she is a target -- for reasons she doesn't really understand. So she escapes on a ship heading to -- New Dresden.

A variety of other people are also involved. The coming attack on New Dresden is something the UN wishes to prevent, and the agent assigned to the problem is Rachel Mansour, heroine of Singularity Sky. She and her husband Martin Springfield end up on the same ship with Wednesday. So does a veteran political blogger named Frank. And so too are representatives of a vile group of Nazis-in-Space(tm). It appears this last group may have something to do with the problems at both Moscow and New Dresden. They are determined enemies of the Eschaton. And they have a special interest in Wednesday, and whatever she may have learned ...

It's a fast moving and fun story, with plenty of pretty neat ideas. It's a bit more smoothly written than Singularity Sky. It resolves intelligently and fairly satisfyingly -- perhaps there is just a hint of the over-convenient about the conclusion. Oberndorf's review also points out, quite sensibly, that Stross's imagination, so fecund at times, fails him at other times. One way is that all his worlds seem pretty bland (though this is actually explained by the terraforming action of the Eschaton). Another problem is the way Wednesday is portrayed -- as a pretty typical disaffected 90s goth girl, to a first approximation. In sum -- a good book, one of the better SF novels of the year, but no more than good.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)