by Rich Horton

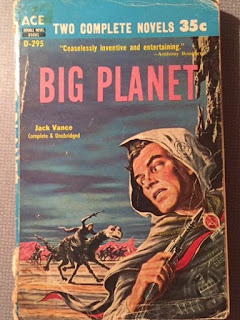

I'm dipping again into my reserve of Ace Double reviews written a long time ago, as I haven't finished my latest Old (non)-Bestseller. But this book seems important to me, as it's by one of SF's greatest writers, and it features a couple of fairly interesting early works. Also, as I have lost my web host for my home page, and haven't found a new one yet, it's nice to get some of the older posts back online.

Jack Vance (real name John Holbrook Vance) was born in 1916, and died in 2013. He was one of the most original of SF writers, and had a remarkably characteristic prose style. He has been one of my favorite writers for a long time.

|

| (Cover by Ed Emshwiller) |

Somehow right from the beginning Don Wollheim decided that Jack Vance books should be backed with Jack Vance books. Did he think Vance so individual an author, so unique in appeal, that he was best marketed as a unit? At any rate, this is the first of 7 Ace Doubles (not counting reprints and repairings) to feature Vance, and all but one of them had Vance on both sides. This book features two novels originally printed in single issues of Standard Magazines/Better Publications pulps: Big Planet in the September 1952 Startling Stories, and Slaves of the Klau, under the title "Planet of the Damned", in the December 1952 Space Stories. Both original magazine publications were full-length novels, in fact, both were longer than the subsequent book versions. Big Planet was abridged for its hard cover publication by Avalon in 1957, and this shorter version is the one reprinted in this Ace Double. It is a bit over 50,000 words long, while the magazine publication was at least 60,000 words. Slaves of the Klau is more like 42,000 words in this edition, and it was somewhat over 50,000 words in the magazine. The original versions of each were restored in the Underwood-Miller limited editions of 1978 and 1982 respectively, with Slaves of the Klau retitled Gold and Iron. (Its third title.) For the Vance Integral Edition Vance's original, darker, ending to Gold and Iron was restored (I'm not sure if that's the case with the Underwood-Miller book.) I have also read somewhere that a longer manuscript version of Big Planet, cut for first publication, was later lost -- I'm not sure if that's true, or if that's someone's garbled version of the the way it was cut for the early book editions.

Big Planet is one of Vance's best remembered early novels, and justifiably so. He had not yet quite developed his mature prose style (except for much of The Dying Earth), but traces of it definitely shine through in this book. And his delight in inventing odd societies is fully evident, as well as his usual hint of misogynism. (The latter present too in Slaves of the Klau.) Moreover, while Big Planet is to some extent a travelogue (one of Vance's most preferred modes), it also has a decently constructed plot with a satisfactory resolution.

Big Planet is a very large metal poor planet, fully inhabitable by humans. It has become a sort of repository for misfits tired of the regimented life on Earth, and a vast array of oddball groups have settled there over the centuries. The lack of long distance communications, and the sheer size of the planet, have meant that most societies have stayed fairly independent and isolated. But now it appears that one ruler, the Bajarnum of Beaujolais, has designs on conquering a large part of the planet. A new commission has been sent from Earth, led by Claude Glystra, to try to stop the Bajarnum, who is actually an Earthman named Charley Lysidder. But their ship is sabotaged, and they crashland near Beaujolais, but 40,000 miles from the Earth Enclave.

Glystra and his fellow survivors decide to try to make it to the Enclave -- but they have only local transport for their journey. Joined by a beautiful local girl, they begin the long journey. The novel, then, consists of this perilous trip, during which member after member of the group meets his death. They encounter some of the Bajarnum's soldiers amid a forest inhabited by men living in treehouses, nomadic raiders, a dangerous river crossing menaced by a plesiosaur-like monster, a town called Kirstendale with a delightful economic system that seems to allow everyone to live in luxury, an elevated sail-propelled sort of train (an idea he reused in one of his much later Anome books), and finally the Oracle of Myrtlesee. Glystra quickly realizes that one of their number must be a traitor, but who he cannot guess.

|

| (Cover by Ed Valigursky) |

Slaves of the Klau is not as good, and indeed it is surely one of Vance's least-known novels. Though I still enjoyed it fairly well. As the story opens, Earth is occupied, very benignly, by a few members of the Lekthwan race, a very humanoid (to the point of being typically beautiful, if unusually colored) people who have given humans the benefits of some of their advanced tech. But Roy Barch, an employee of one of the Lekthwan administrators, is suspicious -- he believes the Lekthwan influence, even if well-intended, will stunt Earth's development. He is also somewhat hopelessly under the spell of the beautiful daughter of his employer. One night he takes her on a date -- resulting only in frustration as she makes it clear that she regards him as a hopeless primitive -- but on returning to the Lekthwan estate he finds all the residents murdered. He and Komeitk Lelianr, the Lekthwan girl, are rounded up by the attackers, the brutish Klau. It seems the Klau are evil slavers, trying to take over the galaxy, and given only token resistance by the virtuous but ineffective races such as the Lekthwan.

The course of the rest of the story is predictable -- upon arriving at the slave planet, Roy finds a way to escape with "Ellen" (as he calls Komeitk Lelianr), despite her ennui and her conviction that resistance is hopeless. After hooking up with a grubby bunch of escapees, Roy eventually hatches a desperate plan to make a spaceship from scratch and head back to Earth. Vance elaborates this rather routine plot pretty well -- Roy's efforts are far from fully successful according to his plans -- though they do end up having the desired effect; and Komeitk Lelianr doesn't immediately jump into Roy's arms. It's not a great novel at all, but it's enjoyable in the terms of early 50s pulp SF, and it prefigures later Vance pretty well, particularly in the character of Komeitk Lelianr, who is the standard late Vance aloof, superior, woman. The only departure is that at the end she comes back to Roy (admittedly somewhat hesitantly), while in later Vance she would have been more likely to meet a bitter end. (And I don't know how his preferred version, Gold and Iron, ends, but I suspect this is one aspect that changes.)

I read Big Planet in that Ace edition when it hit the spinner rack in my hometown and became a Vance fan for life.

ReplyDeleteOne of my favorite ACE Doubles features THE LAST CASTLE on one side and THE DRAGON MASTERS on the other side. Classic Jack Vance!

ReplyDeleteI found Big Planet to be rather overrated.

ReplyDeleteBTW, if you think Jack Vance was a misogynist, you should read Abercrombie Station.

My preference would be to say that Vance's novels often showed a hint of misogyny in the treatment of the females leads, to to claim that he himself was a misogynist. (Just for the record.) This is particularly obvious is the depiction of the game Hussade in the three Alastor Cluster novels.

DeleteAnd, yes, I've read "Abercrombie Station", and its sequel "Cholwell's Chickens". The depiction of Jean Parlier certainly could be seen as misogynist in flavor, yes.

This isn't, I would argue, a bad thing as long as the implication isn't that all women are like Kometk Lolianr or like Jean Parlier, and I wouldn't say that's the implication to take from Vance's oeuvre. (In at least one of the Alastor novels the depiction of the fate of the women in the Hussade games is very uncomfortable, but that's also, I think, to be seen as an indication of the terrible nature of the society in question.)

So you consider the creation of a strong individualistic heroine like Jean Parlier as an act of misogyny? Incredible.

ReplyDeleteFor your information: both Big Planet and Slaves of the Klau, in that Ace Double, are severely abridged from their original appearances in Startling Stories and Space Stories, as we discovered when preparing them for the VIE. In the case of Big Planet, even character names are changed for no apparent reason (well, in one case the reason is known, thanks to Norma Vance: Heinzelman the Hellhorse was changed to Atman the Scourge because it was feared the former would be taken for Jewish!).

The main changes to Planet of the Damned, yielding Slaves of the Klau, had the effect of emasculating the character of Komeitk Lelianr and extirpating her relationship with Barch: she doesn't exactly jump into his arms--that would not be in character--but she does carry his child. That the version in Space Stories is as Vance originally intended it is confirmed by the Ace setting copy, now in the possession of the Vance estate, which retains the author's text while exposing the editor's blue pencil.

The only mass market editions of these stories that are as Vance originally wrote them are those published by Spatterlight Press, which reflect the VIE's restorations and, in the case of Gold and Iron, the evidence of the manuscript mentioned above.

Your mention of the misuse of women in hussade indicates that you understand that an author may depict aspects of a society of which he does not approve. This is especially true of Vance, who very rarely judges what he depicts. He pays his readers the compliment of assuming they are capable of making up their own minds.