Readercon 2023

Readercon is a Science Fiction convention focused on the written word. I had intended to come to it for a long time, but various things intervened, most obviously in recent years the pandemic. This year I finally made it. One reason is that I had an official (of sorts) role -- I am a member of the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award jury, and that award is presented at Readercon.

Thursday

Readercon is held in the Boston area, lately in Quincy, a suburb to Boston's south. As it happens, my father was born in Massachusetts, in Hadley in the west central part of the state. I decided to come in on Thursday and head out to Hadley to see the house Dad grew up in. Jim Cambias, an SF writer I've known for a number of years, also lives in that area, and he had recommended a used book store in Hadley, Grey Matter. I stopped first at my Dad's old house -- I had visited it a couple of times when my Nana was still alive, in 1969 and 1973. (Also in 1960, when my Poppy was also alive, but I don't remember that!) The house is, remarkably, still there, though as the picture here shows, maybe not in such great condition. Right across the street is Hopkins Academy -- where Nana taught and Dad went to school. Founded in 1664!

Then I went on to Grey Matter, and met up with Jim. It is indeed an excellent used book store, and I bought severeal books (Cather's Song of the Lark, Charlotte Bronte's Villette, a few more.) Jim had invited my to dinner at his house, and he went home to start cooking. To give him some time, I headed to Easthampton, and Kelly Link and Gavin Grant's bookstore, Book Moon. I bought another book (Prodigies, by Angelica Gorodischer) and chatted with Kelly and Gavin for a while.

Dinner (lamb with chickpeas) was wonderful. Jim's wife Diane Kelly and their son Robert were there as well, and the conversation was excellent too, touching on such things as Diane's yeoman efforts to introduce her students to classic movies. Then I headed to Quincy -- I had a 9 o'clock panel, on The Trashy and the Sublime, that is, Highbrow vs. Lowbrow literature. (I suppose the general consensus is that historically that distinction has been so class-marked as to be all but meaningless; which is a good observation. That said, I still believe there is a worthwhile distinction -- I don't think that Dan Brown and George Eliot, just as an example, are on a similar level, just because Brown sold a whole lot of books.) Fellow panelists were Gillian Daniels, Emma J. Gibbin, and Yves Meynard.

After the panel I spent a nice time talking to Greg Feeley, whom I have known for some time both online and in-person, Neil Clarke (same), and Michael Dirda, who I have known online for a while but was delighted to meet for the first time in person. And then I finally checked into my hotel room! (I got to the con with no time to spare to, you know, put my suitcase in my bedroom, before the panel.)

Friday

My only official obligation on Friday was the announcement of the Cordwainer Smith award, part of the opening ceremonies (at 10 PM!) So the rest of the day was free, for panels, food, book shopping, etc.

I decided to do breakfast at the hotel (the nearest restaurants required driving, unless you were Scott Edelman.) It was (as expected) pretty routine, and overpriced. I did take the time to go through the dealers' room. As you might hope, it's very book-focused at Readercon. I didn't buy a whole lot. (Well, I'll show a picture of all the books I got later on. Remember -- some were free!) Much of the day ended up in extended conversations. Which is really the point of a con anyway!

I did attend the panel on the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, featuring co-editor John Clute (who has been with the Encyclopedia since the first print edition in 1979) and managing editor Graham Sleight. The panel focussed on the recent transition to the Fourth Edition -- the first two editions (1979 and 1993) were print, in 2011 they went online with the support of Gollancz, in 2021 the Fourth Edition was established, independently. This is truly a fundamental resource, one I check constantly, and the work of maintaining it is literally endless. They rely primarily on contributions, and I do recommend you visit the site and contribute if you can. (It's pretty easy!) John and Graham told a lot of stories, discussed their methods, problems, focus. It was a wholly interesting panel.

I also looked in on Jim Kelly's Kaffeeklatsch, and as it wasn't quite full, I joined it. Jim is always great to talk to -- we had several occasions for (all too brief) chats throught the con.

Dinner was at the hotel restaurant again, this time with Greg Feeley and his wife Pamela. I think this was the first time I've met Pam in person. We had a good conversation -- in many ways a continuing part of an ongoing conversation with Greg that last the whole con. As Greg put it, we "settled everyone's hash". The dinner -- was fine, but, of course, overpriced. Ah, yes, hotel restaurants.

Maybe this is the time to sneak in an announcement. One of the subjects that came up with multiple folks over the weekend was, well, the state of publishing. Given my age, and the age of many of my friends, the state of publishing for older writers is an issue. And -- well, it's affected me. Not because of my age, I hasten to add -- more, I think, a general malaise in the market for short fiction in print. My Best of the Year anthology series, which has run since 2006, 16 years worth through 2021 (19 books), has been, at least temporarily, discontinued. The 2021 book was electronic only -- pandemic supply issues (and pandemic personal issues, too) were a big reason. But my publisher, for various reasons, hasn't been ready to publish subsequent issues, and finally pulled the plug recently. This is a blow, needless to say. And it's a wider concern. Jonathan Strahan's BOTY has also been discontinued. Neil Clarke's continues, for now, as does John Joseph Adams' "Best American" book (a different, and quite valuable, beast.) And Allen Kaster has been doing a very solid series of books for a few years -- but I don't think his books get wide distribution. I think there's still a place for an anthology like mine -- SF and Fantasy -- and I hope to find a way to continue it, either with another publisher, or by some other avenue.

Having said that, I note that lots of great fiction is not finding a publisher. And -- for quite understandable reasons -- many of the authors who have lost their publishers are older. That doesn't mean their books aren't excellent -- it just means that publishers aren't getting in on the ground floor of an exciting career, they are instead publishing the last few books of a distinguished career. And perhaps that doesn't excite them as much. And now -- I hope this won't embarrass him -- I'll mention a novel Greg Feeley has written, Hamlet the Magician. I have had the chance to read an excerpt, and I have to say -- it's wonderful. It truly is. If the potential of that excerpt is maintained (and I don't see why it wouldn't be) this could be a true Fantasy classic. But ... it hasn't found a publisher. Let's just say -- I live in hope, and it's something I look forward to sometime reading in its full form.

Okay, enough of that industry talk! On to the Cordwainer Smith Award. It was exciting to give this in person. Ann VanderMeer and I presented it, representing the jury (the other two members, Steven H Silver and Grant Thiessen, were not present.) The winner is Josephine Saxton. I give a fuller acount here.

Immediately following was a new Readercon "Meet the Prose" event. In the past this was just a gathering, where fans and prose mingled. This year they tried a sort of "speed dating" format -- three pros sat at a table, and fans in groups of three sat in for a few minutes. I confess I was skeptical and didn't sign up myself (in part because I don't think I'm enough of a "pro" that folks would want to "meet" me) -- but by all accounts it was quite successful. I spent some time chatting with folks in the con space, and some time at the bar -- or at the nice outdoor patio space, but didn't stay too late.

Saturday.

This was my heavy panel schedule day. I had a very good night's sleep, and skipped breakfast -- I really wasn't hungry. I went to the con space at 11 and watched the panel about Arthur Machen. I've been aware of Machen for a long time, but have never tried him. But this panel really convinced me I should try him -- and indeed, I have a copy of The Great God Pan/The Hill of Dreams on its way to me! The panelists were Michael Cisco, Elizabeth Hand, Michael Dirda, The Joey Zone, and Henry Wessells. It occurs to me that there is a mode of horror that works for me -- Robert Aickman, Thomas Ligotti, Kelly Link, and, yes, Elizabeth Hand. Perhaps my avoidance of horror is based on the slasher stuff I remember from the late '90s (and some of the super low-end magazines I reviewed for Tangent!) Anyway, Machen sounds totally worth a look.

My three panels were at 3, 6, and 8. The first was Non-Narrative Fiction -- that is, stories told through things like emails, blog posts, FAQs, found objects, etc. (And letters!) My fellow panelists were MJ Cunniff, Sarah Pinsker, and Ken Schneyer. We had a good discussion citing examples of those stories, reasons why to use that sort of storytelling strategy, and so on. I moderated -- I hope moderately. I think it went well.

Next was The Works of D. G. Compton -- who was the previous Cordwainer Smith Award winner. Readercon practice is to discuss the award winner at length at the con following the award. I moderated again. Fellow panelists were Brett Cox, Steve Popkes, and Greg Feeley. We each covered one of his novels at some length, and mentioned a few more. Novels mentioned were The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe (and its sequel Windows), Chronocules, Ascendancies, and Farewell, Earth's Bliss. I mentioned David's new novel, And Here's Our Leo. Compton is a remarkable and original novelist, who really should be read more widely.

My third panel was on Bodice Ripping, Hard Boiling, and other Improbable Literary Joys. The idea was to discuss clichés that are basically impossible, or, any lazy use of improbable or impossible or incorrect science (or history) in a story. Unfortunately a couple of panelists dropped out in advance because they wouldn't be able to make the convention, and another got sick and had to leave. So I was the only one left! I did the only thing I could, and asked the audience to help, and they came through excellently.

I didn't do breakfast, as I said, and there wasn't really time for dinner. But I did have a nice lunch, again at the hotel. I ate with Greg and Pam Feeley again, and also met for the first time a long-time Facebook friend, Hyson Concepcion. Also along were Steve Dooner, and (I hope I get the name right) Tom Olivieri. We had a good talk, about many subjects, a lot centered around teaching issues, as most everyone there was a teacher. (I'm not, but my family is chock-full of them -- my grandmother, my mother, my wife, my daughter, my daughter-in-law -- even my Dad taught community college classes on how to pass the state sanitation test for restaurant folks for years.) One big subject was AI, and students cheating via AI.

This time I stayed out pretty late, had some drinks and talked to lots of people, mostly on the patio. In particular I spent a long fun time talking with Sheila Williams.

Sunday.

Sunday was a light day. I did sleep late -- a good thing (especially as events turned out!) I didn't eat much, though I did have a cannoli provided by Scott Edelman. (Of course I said it would be better if I took the gun and left the cannoli.) (And alas I missed the donuts Scott brought the previous day.) The only panel I attended was a reading, by Rick Wilber, who I'm always glad to see, partly because he has St. Louis roots and indeed grew up just a couple of miles from where I have lived for the past nearly 30 years, and attended church at Mary Queen of Peace, very close to my house indeed. (Walking distance, actually, though a longish walk.) Rick read an intriguing time travel tale about a Scottish politician from the near future traveling back in time to about 210 A.D. and meeting (well, more than just meeting!) the Emperor Septimius Severus.

Oh, and I also checked in at the Serial Fiction panel, mainly to get a chance to talk to Kate Nepveu, a veteran of the glory days of Usenet, especially rec.arts.sf.written. It was neat seeing her. I also talked for a while with another rasfw vet, Paula Lieberman.

Other than that, more conversations, mostly farewells. I did talk for some time to my friends Claire Cooney and Carlos Hernandez, who made me insanely jealous telling of seeing the new production of Sweeney Todd on Broadway. Sweeney Todd is one of my favorite musicals (maybe my favorite), and I've seen it twice in St. Louis, at the Opera Theatre and at the Muny (two diametrically opposite venues!) -- plus of course I've seen the movie. This new production seems tremendous.

The meat of the weekend, of course, was conversation. That's what makes a con! I'll try to list everyone I spoke with, some old friends, some new -- but I know I'll forget some. (I really should either take notes or write these things immediately I come home!) So -- I talked with Greg and Pam Feeley, Michael Dirda, Neil Clarke, Mark Pitman, Barney Dannelke, Claire Cooney, Carlos Hernandez, Sarah Smith, Rick Wilber, Jim Kelly, Ken Schneyer, Hyson Concepcion, Steve Dooner, Tom Olivieri, John Clute, Elizabeth Hand (all too briefly), Kate Nepveu, Paula Lieberman, Sheila Williams, Gary Wolfe, Dale Haines, Ann VanderMeer, Ellen Datlow, Jeffrey Ford, Sally Kobee, Joseph Berlant, Peter Halasz, Henry Wessells, Sarah Pinsker, Alexander Jablokov, A. T. Greenblatt (all too briefly), Charlie Jane Anders, Annalee Newitz (both too briefly as well!), Diane Martin, Ellen Kushner, Eileen Gunn, Elizabeth Bear, Yves Meynard, Gillian Daniels, Gwynne Garfinkle, Michael Swanwick, Greer Gilman, Robert Redick, Arula Ratnakar, Scott Andrews, Scott Edelman, Zig Zag Clayborne. And Greg Bossert!

There were some people I hoped to see but didn't quite connect with: Matthew Kressel, Arley Sorg, Chris Brown, Karen Heuler, Christopher Mark Rose, Filip Hadar Drnovsek Zorko, John Wiswell, Robert Kilheffer, Nikhil Singh, Eric Schaller, Benjamin Rosenbaum. There was one other person I would have dearly dearly loved to meet -- he was listed among the participants, but I don't know if he made it: Eugene Mirabelli.

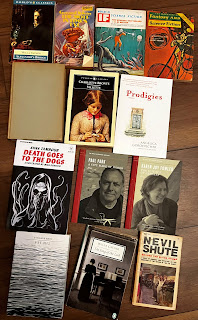

Oh, and I bought some books, and I got some for free. I'll just post a picture! I guess I should mention the titles: the blank one is

Tales of Adventurers, by Geoffrey Household. There's

Alexander's Bridge and

The Song of the Lark, by Willa Cather;

The Mote in Time's Eye, by Gerard Klein; issues of

If and

F&SF;

Villette, by Charlotte Bronte;

Prodigies, by Angelica Gorodischer;

Death Goes to the Dogs, by Anna Tambour; Outspoken Writers books by Karen Joy Fowler and Paul Park;

The Sea, by John Banville (cleverly shown upside down in the picture!) and

Beyond the Black Stump, by Nevil Shute.

Then came the trip home. Well. As you may have heard, there's been some rain recently in the Northeast. Lots of rain. And there was a lot on Sunday. I started getting messages from Southwest Airlines that there might be delays at the airport. I called them, and it looked like the flight I was taking would be delayed by three hours out of Boston. It connected through Chicago Midway. That flight was delayed too -- but only by one hour. You can do the math and see that I wasn't going to make that connection. It looked like I had two options ... stay in Boston for another day and catch a flight out at ... 7:30 PM Monday. Or catch the flight to Chicago, miss my connection, and sleep in the airport and catch an early flight the next morning. I even called my brother Pat, who lives in the city, to see if I could stay with him instead of the airport, but there were, er, complications!

I decided to head to the airport, and see what would happen. I got there, turned in the rental car, and got in Southwest's full service line. People in front of me had similar problems. One woman -- who looked like she might be from Germany -- spent 15 minutes at the counter, and suddenly the Southwest rep told her -- seeming surprised -- that he had a solution! She looked ecstatic, then rushed off to catch her new flight. The next was a family of three -- two adults and their young adult daughter. They seemed to be scheduled on the same flight to Chicago as I was, with similar connection problems. It looked like maybe the daughter could be put on a flight, but there wasn't room for all three. They left, disappointed. I went up to the counter, started to explain my problem, and the rep said, let me handle it. And within a minute or so he found a seat on a supposedly full nonstop flight to St. Louis. It was supposed to leave at 6:55 (and it was already 6:30 or so) but no problem, it was delayed a few hours. I was delighted to take it!

So I went through security, and to the gate, and the flight was leaving at 11:10 or so, getting in to St. Louis after 1:00 AM. Hey, that beats sleeping at Midway Airport and not getting to St. Louis until early the next morning! So I tried to get some dinner -- went to a pizza place in the airport which as soon as I walked up announced it was closed. The other restaurant had an enormous line. So I settle for a frankly terrible sandwich at a "New England Market" or something. And I sat in the lounge for a few hours. I did get to talk to a youth hockey team from Ottawa. I had actually seen a couple of them in the hotel, and they had said they were Blues fans (because the Senators are so bad.) They were in Boston for a tournament, and now were heading to St. Louis for another tournament. Nice kids, and they got my Letterkenny references instantly.

Finally time came for the flight. The flight attendant was nervous as we boarded -- weather was coming to St. Louis, and if we didn't get there in time we might have been diverted to Indianapolis. But, thankfully, we got in just in time. There was thunder and lightning -- but mostly to the south. Mary Ann picked me up, I went home -- and slept in my own bed!

Bottom line is simple -- this was a wonderful convention, I'm thrilled to have gone, the weekend was great fun -- and it's just so cool to be connected to my SF community after the years of the pandemic.

.jpg)