a review by Rich Horton

|

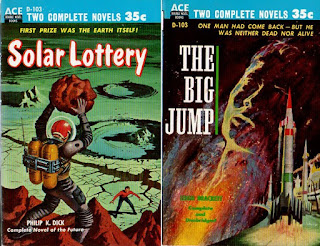

| (Covers by Ed Valigursky and Robert E. Schulz) |

It is a pretty significant book for an Ace Double -- two major writers, each of who would surely have been a Grand Master had they not died too soon. Each have writing credits on major SF movies, Dick of course for the original novel behind Blade Runner (and for quite a few other films of varying quality), and Brackett for the first version of the screenplay of The Empire Strikes Back. They are very different writers, but each very important in their own way.

Solar Lottery was Philip Dick's first novel, and this 1955 Ace Double was its first edition. (There was a UK hardcover a year later retitled World of Chance.) It seems to be reasonably well regarded but I must say I found it a mess. It's set in a future in which the leader of the Solar System is chosen by lottery. The current leader, Quizmaster Verrick, has held the position for 10 years, even though assassins are selected by lot to try to kill him. Most of society is controlled by corporations that rate people, theoretically according to their abilities. People swear allegiance to individuals or corporations. As the novel opens, Ted Benteley is at last able to legally escape his allegiance to his corporation, and he travels to Batavia (now Djakarta, of course) in Indonesia, seat of the government, to try to work for the Quizmaster. Unbeknownst to him, however, a new Quizmaster has just been selected, an "unclassified" named Leon Cartwright. Benteley is fooled into swearing direct allegiance to the old Quizmaster.

Cartwright has long been a Prestonite, devotee of the mad theories of John Preston, who believed in a tenth planet beyond Pluto called Flame Disc. Cartwright has just supervised the launch of a spaceship intended to reach Flame Disc, and his only hope of his new Quizmaster position is to buy time for the ship to reach Flame Disc before Solar authorities stop it. As soon as he becomes Quizmaster, Verrick sets in place a plan to fix the lottery for the assassin, and to use a remote controlled android as the next assassin. This, along with a clever scheme to sequentially control the android with different people, will allow his assassin to evade the telepathic protectors of the Quizmaster.

So it's kind of a wild, uncontrolled, mix of elements, some clever, some interesting, some just loony. The plot sort of reels along, as Ted is shanghaied to being one of the assassin's controllers, and also as he fools around with an ex-telepath girl now working for Verrick, while his true destiny, natch, is to work with Cartwright and become the next Quizmaster, hopefully in so doing restoring sanity to Earth's government. Everywhere traces of Dick's impressive imagination, as well as various of his obsessions, are clear -- but nowhere do things cohere, nowhere to they make even the weird sense that Dick made in his better novels.

The Big Jump was first published in the February 1953 issue of Space Stories, and this Ace Double was its first book publication. It is some 42,000 words, and I believe the book and magazine versions are essentially the same. It's a curious sort of book, spending much of its length in Brackett's "hard-boiled" mode, and for that portion its not very successful. But right toward the end it effectively switches to her high-romantic mode, and that brief portion is rather nice.

Arch Comyn is a spaceship construction worker. He hears that somebody has completed "the Big Jump" -- travelled to another star. He learns that his close friend Paul Rogers was on the crew. However, details about the expedition have been suppressed. Comyn hears a rumor that the survivors are hidden in a hospital on Mars owned by the Cochrane Company (which built the spaceship involved). Comyn makes his way to Mars and rather implausibly barges into the Cochrane complex, and finds the hospital room with the one survivor, Captain Ballantyne. Ballantyne is dying, but Comyn hears him say just a bit -- a hint about "transuranics". Then Ballantyne dies, and Comyn is in the custody of the Cochrane Company, who try to beat his secret out of him. Eventually they let him go, and he heads back to Earth, concerned that the secret of what Ballantyne found on a planet of Barnard's Star will be of altogether too much interest to several parties. And indeed, Comyn detects a tail -- but then he sees Cochrane heiress Sydna Cochrane on TV, making a toast to Ballantyne and hinting that a visit from Comyn would be welcome.

Soon Comyn is confronting Sydna, though not before shaking two separate tails, one of whom tries to kill him. Sydna, who is 100% pure Lauren Bacall (remember, this is Brackett in her "tough guy thriller" mode), convinces Comyn to follow her to the Cochrane complex on Luna. Once there, Comyn to his horror sees what's left of Ballantyne -- even though he is dead, his body somehow still lives mindlessly. Before long, he is a) having an affair with Sydna, and b) pushing to join the second expedition to Barnard's Star. After some more hijinks (another assassination attempt), Comyn and a few Cochranes (and some redshirts) are on their way to Barnard's Star. One of the "Cochranes" is William Stanley, a weaselly cousin-by-marriage who lusts after Sydna despite his married state. Stanley reveals that he has stolen the lost logs of the Ballantyne expedition, and he uses this vital knowledge to negotiate controlling interest in the prospective Transuranic company.

Then they arrive at Barnard's Star, and the novel changes tone entirely, to something transcendental, much more reminiscent of the best of Brackett's planetary romances. The other members of the first expedition are found, living in a primitive state with the presumptive natives of the planet. (Natives who seem to be fully humanoid for no reason at all!) Comyn finds his friend Paul Rogers, who refuses to return to Earth. It seems that beings called the Transuranae, composed of transuranic elements, have conferred immortality and freedom from conflict and want on the inhabitants of this planet. So once again we confront the choice -- intellect, striving, knowledge vs. bliss and contentment. (Cf. countless other SF stories, such as "The Milk of Paradise" by Tiptree.) It's no surprise what Comyn chooses (or has chosen for him), but Brackett presents the alternatives in her most evocative style, and really this final section is quite effective.

It's not one of Brackett's best works, but in the end it's decent stuff. The first part, however, is full of plot holes and implausibilities. As well as plain silly stuff like the horror everyone feels at seeing the quasi-living Ballantyne -- still twitching after his death. Spooky, maybe, but not the stuff of Lovecraftian horror as Brackett would have us believe.