I prepared this for an April 1 book group presentation at Left Bank Books in St. Louis. For those coming to this from Patti Abbott's Friday's Forgotten Books, I'm not really suggesting it's forgotten (if perhaps a bit eclipsed by Little, Big and by Aegypt). And it certainly isn't old, nor, alas, a bestseller.

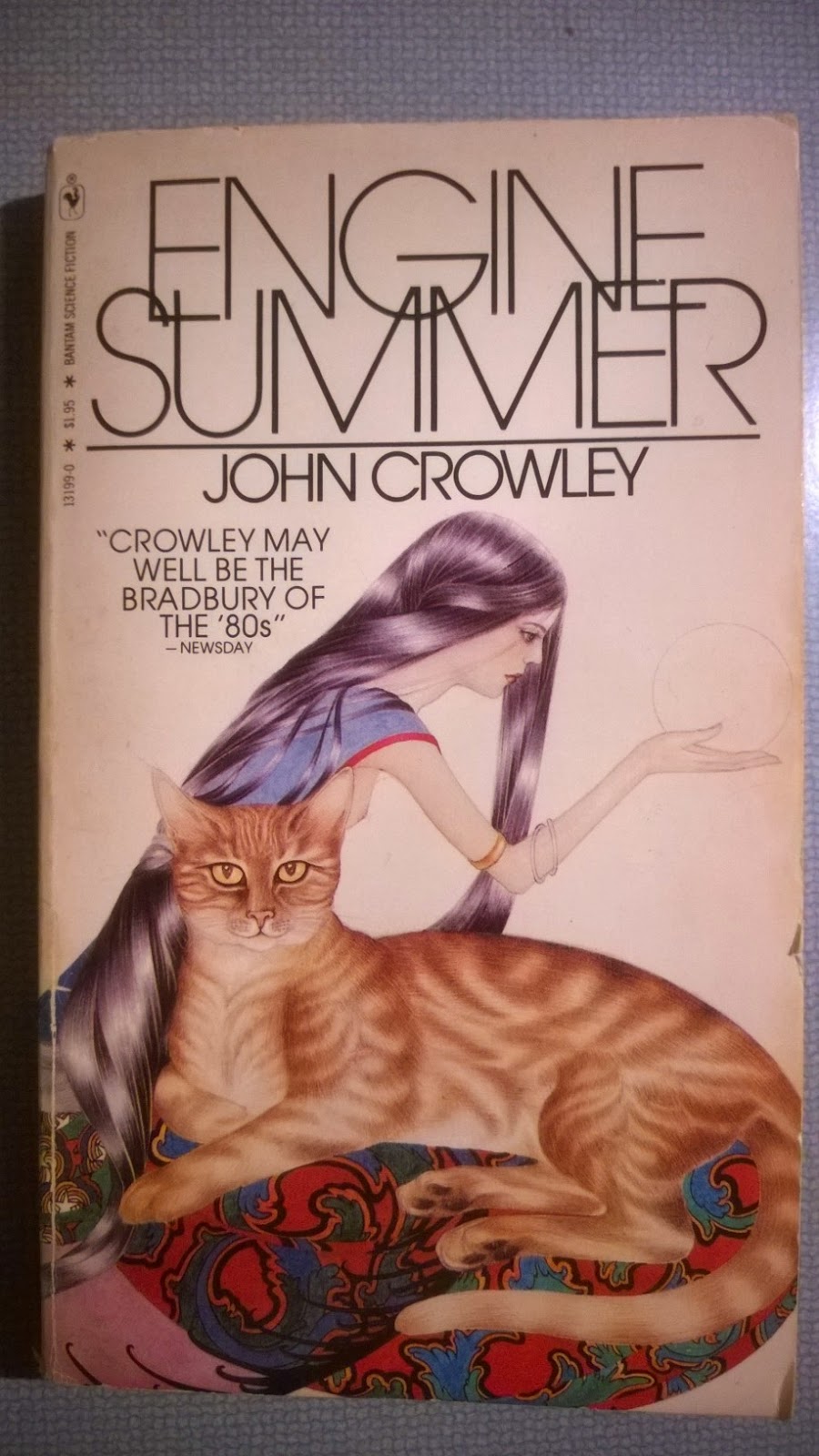

Engine Summer, by John Crowley

Doubleday, 1979

an appreciation by Rich Horton

"Ever after. I promise. Now close

your eyes." So ends John Crowley's Engine Summer, one of my

favorite SF novels of all time. I think that's one of the most

affecting last lines I've ever read, but I have to admit, on its own,

its impact is pretty minimal. Probably that's a feature of great last

lines ... they are great because of what came before. So, what came

before?

Well, first, two previous novels: The

Deep (1975), and Beasts (1976). I found The Deep not long after its

publication, and, expecting nothing much, was really impressed.

Beasts probably got more notice, but though I thought it just fine,

it wasn't as mysterious and original (to my mind) as its predecessor.

Then came Engine Summer, which just detonated in my soul. Apparently

it was Crowley's fourth novel, Little, Big (1981), which detonated in

everyone else's soul, however. I don't want to denigrate that lovely

book, but it is still Engine Summer which is first among his books in

my heart. (Crowley followed up Little, Big with the four volume

Aegypt sequence (which had a difficult path to print) and two

unrelated novels, The Translator and Four Freedoms. Neither should

his short fiction be forgotten: the novellas "Great Work of

Time" and "The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines",

as well as the short stories "Snow" and "Gone",

are thoroughly magnificent, and almost everything else he has

published is nearly as good.)

But I digress. (Snakes' hands, maybe.

Which is an Engine Summer reference.) What is Engine Summer, then? In

a way it is a bildungsroman set in a society which has abandoned even

the possibility of a bildungsroman. In another way it is a

post-apocalyptic elegy, resembling at a distance perhaps Edgar

Pangborn's Davy. It is impossibly bittersweet, and at some level I

can't say why, except everytime I finish it I am in tears. Perhaps

the question is, tears for what, or who? For the main character, Rush

that Speaks, who has lost his love? For the main character, who is

doomed to endless repetition of his story, never knowing how it ends?

For the person the tale is told to (either in the story, or, I

suppose, me), who lives in a world separate from Rush That Speaks'

world, a fragile and isolated world, a world, it would seem, doomed

by its reliance on high technology. For humankind?

The story hinges importantly on its

frame ... it opens with the narrator, in conversation with another

person, denying that he was asleep – he has only closed his eyes.

He opens them, above the clouds, below the sky, talking to an angel,

who asks him for his story. "Shall I begin by being born? Is

that a beginning?". How those lines resonate when the story is

over!

The narrator is a young man named Rush

That Speaks, who grew up in a commune of sorts called Little Belaire.

The first section tells of his young life in Little Belaire, of his

Mbaba (his mother's mother), who raised him, and of his cord (Palm

cord) and his mother and father ... The customs of Little Belaire,

which seem long established and little-changing, are introduced. He

meets a girl named Once a Day (the names of characters in this story

are one of its many wonders), and falls in love with her (over years)

and she leaves to join the wandering Dr. Boots' List. I have of

course elided a great deal.

We slowly gather a bit about this

future ... it is centuries (probably) after an apocalypse called the

Storm. (This is never clearly described, but it seems more an

infrastructure collapse than the result of a war or of an overt

catastrophe.) Most people died, but the Long League of Women had been

planning how to cope for a long time, and they, it seems, enforced

some sort of return to living lightly on the Earth for the survivors.

It's never clear how many people survived, but quite few. Little

Belaire seems to be the descendant of a group, Big Belaire, that came

together towards the close of industrial civilization, before

eventually leaving their home (in a city?) to wander (a time they

call "When We Wandered") until somehow founding Little

Belaire. They call people in their history with important stories to

tell "Saints". And along the way, Rush That Speaks decides

he wants to become a Saint. The people of Little Belaire have one

critical characteristic: they are Truthful Speakers (a Heinlein

allusion?): "they say what they mean, and they mean what they

say".

This being a bildungsroman of

sorts, Rush must leave his home. And so he does, first spending a

year or so with an hermit who Rush thinks might be a Saint, a man

called Blink. Then he wanders further, trying to find Dr. Boots'

List, the group Once a Day joined. There are other wonders: the

Planters, source of the unearthly psychotropic fungus that Little

Belaire harvests and sells; the mystery of the silver glove and the

ball; the mystery of the letter from Dr. Boots; the avvengers; and

the Four Dead Men. And, of course, the question of where (and who?)

Rush That Speaks is as he tells his story.

The story is magnificently written, not

in any ostentatious way, but supremely gracefully. The choices of

names, as I've said, are lovely. The simple descriptions of things –

some familiar to us, some new – are beautiful; and we see things

like "Road" newly as Rush That Speaks describes them. And

the mysteries are made – if not clear, at least perceptible – in

good time, and in a very satisfying way.

Engine Summer is one of my favorite SF

novels of all time, and this reread reinforced my view. (Not a new

view – my votes in the Locus Poll of a few years ago for Best SF

Novels of the 20th Century are public record, and Engine

Summer was on my Top Ten list.) It is heartbreaking in one sense but

arguably nothing terribly bad happens to Rush That Speaks (except the

girl he loves goes away – but to how many teenagers does that

happen, anyway?) It is suffused with a sense of loss, but its world

could possibly be called utopian (from some angles, anyway).