Alfred Coppel, born this date in 1921, wrote a number of stories in the late '40s and early '50s for the SF pulps, but mostly abandoned the field after 1956. There was one more story in If in 1969, and at the same time he expanded his enjoyable space opera novella "The Rebel of Valkyr" to the also enjoyable four volume YA Rhada series, beginning with The Rebel of Rhada, written as by "Robert Cham Gilman". In 1983 he published an alternate history of World War II, The Burning Mountain, in which the US has to invade Japan. Then in the '90s he published a well-received Space Opera trilogy, the Goldenwing Cycle, beginning with the novel Glory. In the mean time he was working in other fields, as he had from the beginning of his career, and he had one major bestseller, Thirty-Four East (1974). Coppel died in 2005.

Coppel's '50's SF was not terribly memorable for the most part, but quite professionally executed. I'm including the bits and pieces I've written about his stories. Alas, I don't have anything on my favorite, the gleefully silly "Rebel of Valkyr", which can be found in Brian W. Aldiss' excellent 1976 anthology Galactic Empires, Volume One. I can, however, reproduce the delightful cover of that issue! (I don't know who painted it, alas.)

Review of Super Science Fiction, November 1950

The other stories include a longish (8500 words) short story by Alfred Coppel. I quite enjoyed Coppel's Rhada series (as by "Robert Cham Gilman"): a YAish Space Opera set complete with horses in the holds of spaceships. These were based on a story from the Fall 1950 Planet Stories, "The Rebel of Valkyr", as by Coppel. Despite this Space Opera, much of Coppel's early 50s SF was more techy in nature, including the story to hand: "Star Tamer", in which a guy starts a "booster" business on the moon, and in an emergency comes up with a new orbit, dangerously close to the Sun, as the only way to get vaccine to Europa in time. (Good thing no teenaged girl stowed away!)

Review of Planet Stories, January 1951

"Task to Luna" by Alfred Coppel uses a variant on a plot I've seen before: Americans and Russians race to the Moon in order to establish a beachhead for Cold War purposes, only to find that the aliens who show up are a much greater menace.

Review of Cosmos, November 1953

Alfred Coppel's "The Guilty" is here to fulfill the official requirement that every issue of every SF magazine in the 50s have a Nuclear War story. This one is about the entire population of the US committing suicide in guilt over having obliterated the Soviet Union (even thought the Russians struck first). Very sanctimonious.

Review of Vortex, Volume 1, Number 1, 1953

Vortex was one of the worst SF magazines of all time. They published only two issues, in 1953. They may be best known for featuring Marion Zimmer Bradley's first two professional sales, in the second issue. The first issue notably featured three writers who made their reputations after leaving the SF field: Milton Lesser, who wrote mysteries as by Stephen Marlowe; S. A. Lombino, who wrote mysteries as by Evan Hunter and as by Ed McBain; and Alfred Coppel. (Both Lesser and Lombino eventually legally changed their names to their more prominent pseudonyms (Hunter in the case of Lombino, instead of McBain).)

[Here are Coppel's two stories.]

"Homecoming", by Alfred Coppel (9500 words) -- after a pointless nuclear war a man tries to return to his wife and kid, only to find them bombed out -- luckily for him he gets to trade up to a younger model, but virtuously only commits to her after mourning his wife. (My cynicism is unfair -- the story is well-enough done, its main weakness being a complete lack of surprises or any hint of originality.)

"Love Affair", by Derfla Leppoc (1100 words) -- a robot falls in love, sort of, with the last surviving human woman. Note the absurd pseudonym (Alfred Coppel spelled backwards), adopted apparently to disguise the fact that Coppel had two stories in the issue.

From a review of Fourth, edited by Gordon Van Gelder

Next is Alfred Coppel's "Mars is Ours" (F&SF, October 1954), a bitter extrapolation of the Cold War to Mars – as purely a 50s story as one could ask for, but still resonant.

Saturday, November 9, 2019

Friday, November 8, 2019

Birthday Review: The Precipice, and four short stories, by Ben Bova

Ben Bova turns 87 today -- and he's still actively writing, with his novel Earth having appeared this past July. (James Gunn is 96 and also actively publishing -- I can't think offhand of another still active SF writer as old.) Here is one review I did of his 2001 novel The Precipice, first in the Asteroid Wars series, as well as two very early stories (his first two, I believe), and two later stories that I reviewed in Locus.

The Precipice, by Ben Bova

Ben Bova's new novel, which on internal evidence seems to be related to his recent [Insert Name of Planet Here] series (officially called The Grand Tour), as well as to the Sam Gunn stories, and other Bova books (I had no idea!), is "The Precipice", just serialized in Analog. I believe the book version is due from Tor any time now. I haven't been reading Bova's novels lately, but I thought having the serial in front of me was a reasonable opportunity to try one. It's pretty much what you might expect -- a solid and fun adventure, with best-sellerish two-D characters, and some strident politics, pro-Space and anti-radical Environmentalism. The villains are really Evull -- they are caricatures. The heroes are a bit better, if not exactly wholly rounded -- but at least they have both good and bad points, indeed, at times they are rather stupid.

The book opens with the US (indeed the world) in environmental chaos, due to the Greenhouse Cliff (or the Precipice of the title) having been reached. But even though the Greens were right about the Greenhouse effect, they, along with other basically evil bureaucrats, resisted means of solving the Greehouse problem: mainly nuclear power, industrialization of space, and nanotech. One of the main heroes is Dan Randolph, the 60ish head of Astro Corporation, who is depicted in a rather unnecessary scene as trying to rescue the former US president, and his lover, Jane Scanwell, as she tries to help refugees from flooding and earthquakes in Memphis. The whole bit about his affair seemed wasted -- I suspect it might be tying up loose ends from earlier books.

Soon he is fielding a proposal from his slimy rival Martin Humphries, to try to develop a small fusion powerplant which will open up the resources of the asteroids to humanity, if it can be made to fit a spaceship. And we're off, as Dan's company, mostly on the Moon, rapidly (kind of like Tom Swift, only slightly more plausibly) develops said spaceship, while Dan appoints two women to be the pilots. One is our other protagonist, Pancho Lane, a savvy black woman with a mission to make enough money, by means fair or foul (but only slightly foul, she has standards), to be able to save her sister's life. The other woman is the incredibly beautiful Amanda (I forget her last name). And soon Dan and Pancho are fighting off threats from Humphries and the various regulators in a race to reach the Asteroids and claim some rocks in time to save Astro Corporation from bankruptcy, and also save the Earth.

It's a fast and enjoyable read, if you kind of ignore the broad characters (the main villain turns out be not just a slimy thieving corporate raider, not just a murderer, but naturally a sexual prevert with designs on Amanda too), and the conveniences such as an invisibility suit showing up just when needed. Certainly not great stuff, and not to everybody's taste, but fun.

Review of Amazing, February 1960

Finally, "The Long Way Back" was Ben Bova's first published short story, though a juvenile novel, The Star Conquerors, appeared from Winston in 1959. Bova ended up writing a great many science articles for Cele Goldsmith, and a few stories. This one is also post-apocalyptic, and somewhat didactic, and the hero is a middle-aged man who has been recruited to repair a power-satellite to beam power to a small enclave of survivors. His price is help investigating the ruins of the cities to recover more knowledge -- but he realizes that he has been betrayed: no one will help him, and in reality he doesn't have enough oxygen to survive the trip back to Earth. But should be betray the whole world? He finds a solution that will benefit the remaining survivors, but not in the way they had planned. The message is pretty solid, but the story is executed somewhat clumsily.

Review of Amazing, January 1962

Ben Bova’s “The Towers of Titan” turns out to be only his second published short story. (The first sale was also to Cele Goldsmith — “A Long Way Back,” Amazing, February 1960). He did publish a Winston Juvenile, The Star Conquerors, in 1959.

The Star Conquerors“The Towers of Titan” is a minor piece (and does not seem to have been reprinted except in one of the Sol Cohen super cheap reprint ‘zines.) Dr. Sidney Lee is a respected scientist who had a breakdown when confronted by the mystery of the mysterious towers on Titan – alien machinery that has been operating for a million years.

At last, he returns, kindling a relationship with a lovely woman scientist (who looks a bit like Carol Emshwiller according to the illustrations), and taking over leadership of the ongoing investigation, all the while convinced that the machines are the product of malevolent aliens. It ends with a sudden revelation about the machines’ purpose (that revelation in itself not too bad an idea).

Locus, June 2003

Ben Bova's "Sam and the Flying Dutchman" (Analog, June) is a Sam Gunn story. These are usually quite amusing, and this one delivers, as Sam flees marriage and tries to help a damsel in distress.

Locus, April 2005

The March Amazing Stories, #609, is available only in electronic form. I hope this magazine gets back on its print feet -- it's been a promising publication so far. This issue includes a Sam Gunn story from Ben Bova, "Piker's Peek", reliable entertainment from a veteran, as Sam inveigles a bitter rival into investing in a Lunar resort project.

The Precipice, by Ben Bova

Ben Bova's new novel, which on internal evidence seems to be related to his recent [Insert Name of Planet Here] series (officially called The Grand Tour), as well as to the Sam Gunn stories, and other Bova books (I had no idea!), is "The Precipice", just serialized in Analog. I believe the book version is due from Tor any time now. I haven't been reading Bova's novels lately, but I thought having the serial in front of me was a reasonable opportunity to try one. It's pretty much what you might expect -- a solid and fun adventure, with best-sellerish two-D characters, and some strident politics, pro-Space and anti-radical Environmentalism. The villains are really Evull -- they are caricatures. The heroes are a bit better, if not exactly wholly rounded -- but at least they have both good and bad points, indeed, at times they are rather stupid.

The book opens with the US (indeed the world) in environmental chaos, due to the Greenhouse Cliff (or the Precipice of the title) having been reached. But even though the Greens were right about the Greenhouse effect, they, along with other basically evil bureaucrats, resisted means of solving the Greehouse problem: mainly nuclear power, industrialization of space, and nanotech. One of the main heroes is Dan Randolph, the 60ish head of Astro Corporation, who is depicted in a rather unnecessary scene as trying to rescue the former US president, and his lover, Jane Scanwell, as she tries to help refugees from flooding and earthquakes in Memphis. The whole bit about his affair seemed wasted -- I suspect it might be tying up loose ends from earlier books.

Soon he is fielding a proposal from his slimy rival Martin Humphries, to try to develop a small fusion powerplant which will open up the resources of the asteroids to humanity, if it can be made to fit a spaceship. And we're off, as Dan's company, mostly on the Moon, rapidly (kind of like Tom Swift, only slightly more plausibly) develops said spaceship, while Dan appoints two women to be the pilots. One is our other protagonist, Pancho Lane, a savvy black woman with a mission to make enough money, by means fair or foul (but only slightly foul, she has standards), to be able to save her sister's life. The other woman is the incredibly beautiful Amanda (I forget her last name). And soon Dan and Pancho are fighting off threats from Humphries and the various regulators in a race to reach the Asteroids and claim some rocks in time to save Astro Corporation from bankruptcy, and also save the Earth.

It's a fast and enjoyable read, if you kind of ignore the broad characters (the main villain turns out be not just a slimy thieving corporate raider, not just a murderer, but naturally a sexual prevert with designs on Amanda too), and the conveniences such as an invisibility suit showing up just when needed. Certainly not great stuff, and not to everybody's taste, but fun.

Review of Amazing, February 1960

Finally, "The Long Way Back" was Ben Bova's first published short story, though a juvenile novel, The Star Conquerors, appeared from Winston in 1959. Bova ended up writing a great many science articles for Cele Goldsmith, and a few stories. This one is also post-apocalyptic, and somewhat didactic, and the hero is a middle-aged man who has been recruited to repair a power-satellite to beam power to a small enclave of survivors. His price is help investigating the ruins of the cities to recover more knowledge -- but he realizes that he has been betrayed: no one will help him, and in reality he doesn't have enough oxygen to survive the trip back to Earth. But should be betray the whole world? He finds a solution that will benefit the remaining survivors, but not in the way they had planned. The message is pretty solid, but the story is executed somewhat clumsily.

Review of Amazing, January 1962

Ben Bova’s “The Towers of Titan” turns out to be only his second published short story. (The first sale was also to Cele Goldsmith — “A Long Way Back,” Amazing, February 1960). He did publish a Winston Juvenile, The Star Conquerors, in 1959.

The Star Conquerors“The Towers of Titan” is a minor piece (and does not seem to have been reprinted except in one of the Sol Cohen super cheap reprint ‘zines.) Dr. Sidney Lee is a respected scientist who had a breakdown when confronted by the mystery of the mysterious towers on Titan – alien machinery that has been operating for a million years.

At last, he returns, kindling a relationship with a lovely woman scientist (who looks a bit like Carol Emshwiller according to the illustrations), and taking over leadership of the ongoing investigation, all the while convinced that the machines are the product of malevolent aliens. It ends with a sudden revelation about the machines’ purpose (that revelation in itself not too bad an idea).

Locus, June 2003

Ben Bova's "Sam and the Flying Dutchman" (Analog, June) is a Sam Gunn story. These are usually quite amusing, and this one delivers, as Sam flees marriage and tries to help a damsel in distress.

Locus, April 2005

The March Amazing Stories, #609, is available only in electronic form. I hope this magazine gets back on its print feet -- it's been a promising publication so far. This issue includes a Sam Gunn story from Ben Bova, "Piker's Peek", reliable entertainment from a veteran, as Sam inveigles a bitter rival into investing in a Lunar resort project.

Thursday, November 7, 2019

Forgotten Book: The Creatures of Man, by Howard Myers

The Creatures of Man, by Howard L. Myers

a review by Rich Horton

Is this book forgotten? Perhaps not -- it was only published in 2003. But the author was all but forgotten until his work was resurrected by Eric Flint and Guy Gordon. They have since pubished another collection, The Reign of Infinity, with his novel Cloud Chamber and a few more stories. Here's what I wrote back in 2003:

Eric Flint (often with the help of Guy Gordon) has been putting out a series for Baen books of collections of stories by older authors, now mostly forgotten. He began with a series of several books by James Schmitz, which when they get around to reissuing The Witches of Karres will have returned all of Schmitz's published stories to print. He has also put together collections by Randall Garrett, Christopher Anvil, Keith Laumer, Murray Leinster, and Tom Godwin. All these authors have long stopped writing, and all but Anvil (real name Harry Crosby) are dead. [Crosby (aka Anvil) died in 2009, after I wrote the first version of this.] All but Laumer were also primarily associated with Astounding/Analog and John W. Campbell. (Laumer published stories in Analog under Ben Bova's editorship, but I don't know of any he sold to Campbell.) (Well, Leinster was prolific enough that you couldn't say he was "primarily" associated with Astounding -- but he did publish a lot there.)

While I've found these collections to be of variable quality (I like the Schmitz books a lot, for instance, but the one Anvil book I read was rather poor), I do think the project as a whole is admirable. Flint has resurrected a lot of competent adventure-style SF of the 50s and 60s -- rarely great stuff but often quite enjoyable. I must admit, though, that I was surprised by his latest project -- a collection of stories by Howard L. Myers, also known as Verge Foray. I knew the name Foray as an Analog writer of the late 60s -- I didn't know the name Myers at all. I had an image of "Verge Foray" as the ultimate "late Campbell" writer. Offhand he didn't seem to me a writer much in need of resurrection. That said, I have to admit I'd read very little of his work -- a couple of Analog stories that seemed psi-obsessed to me, in line with one of Campbell's most annoying hobbyhorses.

So I picked up a copy of The Creatures of Man, ready to give Myers a fair try. This book includes 19 stories, a good portion of his total output. Another 5 or 10 stories and one novel (Cloud Chamber) exist. Myers was born in 1930, and published a story in Galaxy in 1952 ("The Reluctant Weapon" -- a pretty good piece, actually, one of the best in the book). He published nothing more until 1967, when "Lost Calling", as by "Verge Foray", appeared in Analog. He was quite prolific over the next few years, publishing a passel of stories in Analog as well as a few in Amazing, Fantastic, F&SF, If, and Galaxy. He died only 41 years of age in 1971. His stories kept appearing through 1974 -- his last, "The Frontliners", appeared in the July 1974 issue of Galaxy -- the issue just preceding the first one I ever saw. The novel did not come out until 1977. I can only assume that he left a pile of unsold stories which his mother (I'm guessing, but he seems to have been living with his mother when he died) kept marketing. All told, an interesting, and rather sad, career arc. Flint and Gordon assert that had he had the chance to continue developing, he'd have been a major author. I'm not so sure -- the later stories do not seem particularly to show an arc of improvement, though to be fair he may not have quite "finished" those that appeared after his death. I will say that he had some interesting ideas, though his prose was pedestrian, and his characters, especially the women, were totally unconvincing.

How was the book? It's a tale of two halves. The first half has some nice stuff. As I've mentioned, "The Reluctant Weapon", a story about a lazy superweapon abandoned by a long lost Galactic race, and its encounter with a backwoods Earthman, is a pretty fair effort. "Fit for a Dog" is a biting story of an ecologically challenged future earth and the evolved superdogs that inhabit it. "All Around the Universe" is not bad either, about a dilettantish man in the very far future, when the economy depends on "Admiration Points", and his search for a mysterious planet. It's both fairly witty and nicely imagined. And several more stories in the first half of the book betray a pretty fair SFnal imagination.

The second half of the book is devoted to a cycle of stories Flint has dubbed "The Chalice Cycle". Most of these are part of Myers' so-called "Econo-War" series, which began in Analog and concluded (long after his death) in Galaxy. These are set in a post-scarcity future in which two human federations of worlds are engaged in a mostly-nonviolent (with exceptions) "war". The idea is that even though people's needs are easily met, so ordinary competition for resources is unnecessary, people will stagnate without some sort of meaningful struggle -- hence, the "econo-war". The stories' setting reminded me (in a contrasting way) of Iain Banks's Culture, enough so to make me wonder if they weren't among the stories that Banks has said he was reacting to when he devised that setting. At any rate, Myers's take on things seems almost uber-Campbellian.

The various Econo-War stories involve the two sides in the War coming up with technological advances, giving first one side then the other a temporary advantage. There are some cute SFnal ideas involved, mainly the way people travel through space -- naked, with some implanted tech to provide protection, inertial suppression, and breathing, etc. However, I was mostly unconvinced -- I think one story in the setting would have been plenty -- the eventual 6 seemed tedious.

There are two pendant stories. One, "The Earth of Nenkumal", is more a "magic goes away" story -- it's a novella from Fantastic in 1974 that is set in the long past on Earth, when magic is being suppressed by the evil efforts of the "God-Warriors" -- a long period in which religion will take the place of magic, with concomitant misery, is forthcoming, and the hero, a repentant God-Warrior, is recruited to help one of the last magicians hide a powerful good luck charm for eventual use when magic returns. It's an OK story, with a decent twist at the end, but I was severely bothered by the sexual politics. It opens with a gang-bang on a table in a bog-standard fantasy pub -- fully consensual on the woman's part (she's a barmaid), but icky to me nonetheless. (The idea is that in the utopian magic world people are so unhungup about sex they just do it all the time, in public, with pretty much anyone.) It may be totally unfair of me to say this, but when you hear that the writer of such a scene was still living with his mother at age 41 you are hardly surprised. Towards the end the hero rapes a woman who soon after is grateful to him for having done so and asking for more. Ickier still, she is sexually mature but less than ten years old mentally. Perhaps I should have been speculating along with the author about such enlightened non-standard sexual mores, but I couldn't really play along.

The last story is "Questor", and it's about an Econo-War participant who lands on Earth looking for a fabled object which will give the holder good luck. Apparently this is the object hidden in "The Earth of Nenkumal", linking all those stories together. Well, OK, but I really think the link unnecessary and silly. However, "Questor" taken alone is actually a decent story, and interestingly it predates all the other "Econo-War" stories.

(Just to complain a bit more about Myers's sexual politics, the last Econo-War story features a mutated super girl who spends the story looking for a similarly mutated superman with whom to have kids. It wasn't actively offensive like the rape stuff in "The Earth of Nenkumal", but it was cringe-inducing in its portrayal of the woman's attitudes.)

So, in sum, I can't strongly recommend The Creatures of Man. It's an uneven book, with some OK stuff, some promising stories. Nothing I'd call a lost classic, but some pretty fine stuff. On the other hand, plenty of pedestrian stuff, and some downright icky stuff. I'm unconvinced by the editors' argument that Myers had the potential to be a top writer in the field, but I'll allow that if he could have developed his skills he had a decent imagination and he might have done some pretty good work.

a review by Rich Horton

Is this book forgotten? Perhaps not -- it was only published in 2003. But the author was all but forgotten until his work was resurrected by Eric Flint and Guy Gordon. They have since pubished another collection, The Reign of Infinity, with his novel Cloud Chamber and a few more stories. Here's what I wrote back in 2003:

Eric Flint (often with the help of Guy Gordon) has been putting out a series for Baen books of collections of stories by older authors, now mostly forgotten. He began with a series of several books by James Schmitz, which when they get around to reissuing The Witches of Karres will have returned all of Schmitz's published stories to print. He has also put together collections by Randall Garrett, Christopher Anvil, Keith Laumer, Murray Leinster, and Tom Godwin. All these authors have long stopped writing, and all but Anvil (real name Harry Crosby) are dead. [Crosby (aka Anvil) died in 2009, after I wrote the first version of this.] All but Laumer were also primarily associated with Astounding/Analog and John W. Campbell. (Laumer published stories in Analog under Ben Bova's editorship, but I don't know of any he sold to Campbell.) (Well, Leinster was prolific enough that you couldn't say he was "primarily" associated with Astounding -- but he did publish a lot there.)

While I've found these collections to be of variable quality (I like the Schmitz books a lot, for instance, but the one Anvil book I read was rather poor), I do think the project as a whole is admirable. Flint has resurrected a lot of competent adventure-style SF of the 50s and 60s -- rarely great stuff but often quite enjoyable. I must admit, though, that I was surprised by his latest project -- a collection of stories by Howard L. Myers, also known as Verge Foray. I knew the name Foray as an Analog writer of the late 60s -- I didn't know the name Myers at all. I had an image of "Verge Foray" as the ultimate "late Campbell" writer. Offhand he didn't seem to me a writer much in need of resurrection. That said, I have to admit I'd read very little of his work -- a couple of Analog stories that seemed psi-obsessed to me, in line with one of Campbell's most annoying hobbyhorses.

So I picked up a copy of The Creatures of Man, ready to give Myers a fair try. This book includes 19 stories, a good portion of his total output. Another 5 or 10 stories and one novel (Cloud Chamber) exist. Myers was born in 1930, and published a story in Galaxy in 1952 ("The Reluctant Weapon" -- a pretty good piece, actually, one of the best in the book). He published nothing more until 1967, when "Lost Calling", as by "Verge Foray", appeared in Analog. He was quite prolific over the next few years, publishing a passel of stories in Analog as well as a few in Amazing, Fantastic, F&SF, If, and Galaxy. He died only 41 years of age in 1971. His stories kept appearing through 1974 -- his last, "The Frontliners", appeared in the July 1974 issue of Galaxy -- the issue just preceding the first one I ever saw. The novel did not come out until 1977. I can only assume that he left a pile of unsold stories which his mother (I'm guessing, but he seems to have been living with his mother when he died) kept marketing. All told, an interesting, and rather sad, career arc. Flint and Gordon assert that had he had the chance to continue developing, he'd have been a major author. I'm not so sure -- the later stories do not seem particularly to show an arc of improvement, though to be fair he may not have quite "finished" those that appeared after his death. I will say that he had some interesting ideas, though his prose was pedestrian, and his characters, especially the women, were totally unconvincing.

How was the book? It's a tale of two halves. The first half has some nice stuff. As I've mentioned, "The Reluctant Weapon", a story about a lazy superweapon abandoned by a long lost Galactic race, and its encounter with a backwoods Earthman, is a pretty fair effort. "Fit for a Dog" is a biting story of an ecologically challenged future earth and the evolved superdogs that inhabit it. "All Around the Universe" is not bad either, about a dilettantish man in the very far future, when the economy depends on "Admiration Points", and his search for a mysterious planet. It's both fairly witty and nicely imagined. And several more stories in the first half of the book betray a pretty fair SFnal imagination.

The second half of the book is devoted to a cycle of stories Flint has dubbed "The Chalice Cycle". Most of these are part of Myers' so-called "Econo-War" series, which began in Analog and concluded (long after his death) in Galaxy. These are set in a post-scarcity future in which two human federations of worlds are engaged in a mostly-nonviolent (with exceptions) "war". The idea is that even though people's needs are easily met, so ordinary competition for resources is unnecessary, people will stagnate without some sort of meaningful struggle -- hence, the "econo-war". The stories' setting reminded me (in a contrasting way) of Iain Banks's Culture, enough so to make me wonder if they weren't among the stories that Banks has said he was reacting to when he devised that setting. At any rate, Myers's take on things seems almost uber-Campbellian.

The various Econo-War stories involve the two sides in the War coming up with technological advances, giving first one side then the other a temporary advantage. There are some cute SFnal ideas involved, mainly the way people travel through space -- naked, with some implanted tech to provide protection, inertial suppression, and breathing, etc. However, I was mostly unconvinced -- I think one story in the setting would have been plenty -- the eventual 6 seemed tedious.

There are two pendant stories. One, "The Earth of Nenkumal", is more a "magic goes away" story -- it's a novella from Fantastic in 1974 that is set in the long past on Earth, when magic is being suppressed by the evil efforts of the "God-Warriors" -- a long period in which religion will take the place of magic, with concomitant misery, is forthcoming, and the hero, a repentant God-Warrior, is recruited to help one of the last magicians hide a powerful good luck charm for eventual use when magic returns. It's an OK story, with a decent twist at the end, but I was severely bothered by the sexual politics. It opens with a gang-bang on a table in a bog-standard fantasy pub -- fully consensual on the woman's part (she's a barmaid), but icky to me nonetheless. (The idea is that in the utopian magic world people are so unhungup about sex they just do it all the time, in public, with pretty much anyone.) It may be totally unfair of me to say this, but when you hear that the writer of such a scene was still living with his mother at age 41 you are hardly surprised. Towards the end the hero rapes a woman who soon after is grateful to him for having done so and asking for more. Ickier still, she is sexually mature but less than ten years old mentally. Perhaps I should have been speculating along with the author about such enlightened non-standard sexual mores, but I couldn't really play along.

The last story is "Questor", and it's about an Econo-War participant who lands on Earth looking for a fabled object which will give the holder good luck. Apparently this is the object hidden in "The Earth of Nenkumal", linking all those stories together. Well, OK, but I really think the link unnecessary and silly. However, "Questor" taken alone is actually a decent story, and interestingly it predates all the other "Econo-War" stories.

(Just to complain a bit more about Myers's sexual politics, the last Econo-War story features a mutated super girl who spends the story looking for a similarly mutated superman with whom to have kids. It wasn't actively offensive like the rape stuff in "The Earth of Nenkumal", but it was cringe-inducing in its portrayal of the woman's attitudes.)

So, in sum, I can't strongly recommend The Creatures of Man. It's an uneven book, with some OK stuff, some promising stories. Nothing I'd call a lost classic, but some pretty fine stuff. On the other hand, plenty of pedestrian stuff, and some downright icky stuff. I'm unconvinced by the editors' argument that Myers had the potential to be a top writer in the field, but I'll allow that if he could have developed his skills he had a decent imagination and he might have done some pretty good work.

Birthday Review: Stories of Rahul Kanakia

Today is Rahul Kanakia's birthday. He's been publishing SF short fiction since 2006, and while I saw that story, "Butterfly Jesus Saves the World", in the second issue of an interesting small magazine, Fictitious Force, I confess I don't remember it. (Fictitious Force was also interesting for its unusual form factor -- very tall -- somewhat like Rahul, perhaps, though I haven't met him in person.) I started noticing his work early this decade, and the four reviews I present before are of stories that really impressed me, particularly "Empty Planets", one of the finest SF short stories of this decade, and to my mind a sadly underappreciated one. For the past few years he has been focussing on YA novels, it seems, with his first, Enter Title Here, having appeared in 2016, and his second, We Are Totally Normal, due in 2020.

Locus, December 2015

Lightspeed's November issue is a strong one. Rahul Kanakia's “Here is My Thinking on a Situation That Affects Us All” has one of the more original ideas I've seen in a while – not original as in mind-blowing or weird so much as in just taking an unexpected, and fairly logical, look at some some SF tropes from a slant angle. It's told by a spaceship that was buried in the Earth's core by aliens for millions of years, and which has finally emerged. It has a mission – for its makers – and it will not be deviated from it – at least, not much. The spaceship is effectively portrayed as truly non-human, and yet the story becomes something of a love story, though not in any expected way.

Locus, March 2016

Even better is Rahul Kanakia’s “Empty Planets” (Interzone, January-February), my pick for the best story in this young year. David is a child of a family of “shareholders” on the Moon far in the future. Most of his class use their economic heft either to earn procreation rights or to while away their lives in neurological loops, but he decides to pursue “Non Mandatory Studies”, even though the Machine that rules human society assures him he’s not smart enough to contribute anything special. There he meets another sort of outcast, Margery, a “recontactee” from a generation ship that the AI rescued. Margery is particularly intelligent, and she wants to study the potentially intelligent gas clouds of Altair III. David and Margery become close, and in a personal sense their lives follow a conventional story pattern. But nothing I’ve said even hints at the powerful, profound core of this story. The far future setting is pleasant but lonely – no other intelligent species has been found, the Machine seems to be shepherding humanity to extinction (in the gentlest way), and the only important question is “what does it all mean?” Which is, isn’t it, always the most important question? Achingly lovely, truly thought-provoking, sad but not sad. Kanakia has been doing nice work for some time, but this story seems a real milestone.

Locus, April 2018

Lightspeed’s February issue includes a fine and pointed fantasy by Rahul Kanakia, “A Coward’s Death”, about an all-powerful Emperor conscripting the first sons of his subjects to work on a massive statue. The moral is simple – his rule is unjust, but resistance, as they say, is futile. Nonetheless, one young man in the narrator’s village resists. The tale is lightly told but mordant, and effective.

Locus, June 2018

The 12 April issue of Beneath Ceaseless Skies includes a nice piece from Rahul Kanakia, “Weft”, told by a magic user named Thread, who with his two companions is charged with hunting down people who have gained potentially dangerous magical powers and eliminating them. The current subject is a cook’s daughter, and the question arises, what has she done to deserve extermination? Why not let her go? But can they get away with that? And is it really a good idea? All interestingly posed questions.

Locus, December 2015

Lightspeed's November issue is a strong one. Rahul Kanakia's “Here is My Thinking on a Situation That Affects Us All” has one of the more original ideas I've seen in a while – not original as in mind-blowing or weird so much as in just taking an unexpected, and fairly logical, look at some some SF tropes from a slant angle. It's told by a spaceship that was buried in the Earth's core by aliens for millions of years, and which has finally emerged. It has a mission – for its makers – and it will not be deviated from it – at least, not much. The spaceship is effectively portrayed as truly non-human, and yet the story becomes something of a love story, though not in any expected way.

Locus, March 2016

Even better is Rahul Kanakia’s “Empty Planets” (Interzone, January-February), my pick for the best story in this young year. David is a child of a family of “shareholders” on the Moon far in the future. Most of his class use their economic heft either to earn procreation rights or to while away their lives in neurological loops, but he decides to pursue “Non Mandatory Studies”, even though the Machine that rules human society assures him he’s not smart enough to contribute anything special. There he meets another sort of outcast, Margery, a “recontactee” from a generation ship that the AI rescued. Margery is particularly intelligent, and she wants to study the potentially intelligent gas clouds of Altair III. David and Margery become close, and in a personal sense their lives follow a conventional story pattern. But nothing I’ve said even hints at the powerful, profound core of this story. The far future setting is pleasant but lonely – no other intelligent species has been found, the Machine seems to be shepherding humanity to extinction (in the gentlest way), and the only important question is “what does it all mean?” Which is, isn’t it, always the most important question? Achingly lovely, truly thought-provoking, sad but not sad. Kanakia has been doing nice work for some time, but this story seems a real milestone.

Locus, April 2018

Lightspeed’s February issue includes a fine and pointed fantasy by Rahul Kanakia, “A Coward’s Death”, about an all-powerful Emperor conscripting the first sons of his subjects to work on a massive statue. The moral is simple – his rule is unjust, but resistance, as they say, is futile. Nonetheless, one young man in the narrator’s village resists. The tale is lightly told but mordant, and effective.

Locus, June 2018

The 12 April issue of Beneath Ceaseless Skies includes a nice piece from Rahul Kanakia, “Weft”, told by a magic user named Thread, who with his two companions is charged with hunting down people who have gained potentially dangerous magical powers and eliminating them. The current subject is a cook’s daughter, and the question arises, what has she done to deserve extermination? Why not let her go? But can they get away with that? And is it really a good idea? All interestingly posed questions.

Thursday, October 31, 2019

Ace Double Reviews, 115: Solar Lottery, by Philip K. Dick/The Big Jump, by Leigh Brackett

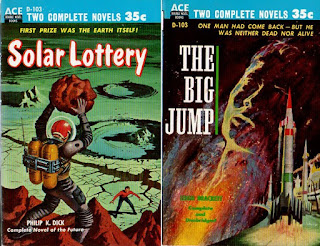

Ace Double Reviews, 115: Solar Lottery, by Philip K. Dick/The Big Jump, by Leigh Brackett (#D-103, 1955, 35 cents)

a review by Rich Horton

I bought a copy of this Ace Double for a surprisingly good price -- Philip Dick's work often costs more than I'm happy paying. I have different editions of both books, but this seemed like a book worth having. So I'm assembling an Ace Double review from my previous reviews of these novels independently.

It is a pretty significant book for an Ace Double -- two major writers, each of who would surely have been a Grand Master had they not died too soon. Each have writing credits on major SF movies, Dick of course for the original novel behind Blade Runner (and for quite a few other films of varying quality), and Brackett for the first version of the screenplay of The Empire Strikes Back. They are very different writers, but each very important in their own way.

Solar Lottery was Philip Dick's first novel, and this 1955 Ace Double was its first edition. (There was a UK hardcover a year later retitled World of Chance.) It seems to be reasonably well regarded but I must say I found it a mess. It's set in a future in which the leader of the Solar System is chosen by lottery. The current leader, Quizmaster Verrick, has held the position for 10 years, even though assassins are selected by lot to try to kill him. Most of society is controlled by corporations that rate people, theoretically according to their abilities. People swear allegiance to individuals or corporations. As the novel opens, Ted Benteley is at last able to legally escape his allegiance to his corporation, and he travels to Batavia (now Djakarta, of course) in Indonesia, seat of the government, to try to work for the Quizmaster. Unbeknownst to him, however, a new Quizmaster has just been selected, an "unclassified" named Leon Cartwright. Benteley is fooled into swearing direct allegiance to the old Quizmaster.

Cartwright has long been a Prestonite, devotee of the mad theories of John Preston, who believed in a tenth planet beyond Pluto called Flame Disc. Cartwright has just supervised the launch of a spaceship intended to reach Flame Disc, and his only hope of his new Quizmaster position is to buy time for the ship to reach Flame Disc before Solar authorities stop it. As soon as he becomes Quizmaster, Verrick sets in place a plan to fix the lottery for the assassin, and to use a remote controlled android as the next assassin. This, along with a clever scheme to sequentially control the android with different people, will allow his assassin to evade the telepathic protectors of the Quizmaster.

So it's kind of a wild, uncontrolled, mix of elements, some clever, some interesting, some just loony. The plot sort of reels along, as Ted is shanghaied to being one of the assassin's controllers, and also as he fools around with an ex-telepath girl now working for Verrick, while his true destiny, natch, is to work with Cartwright and become the next Quizmaster, hopefully in so doing restoring sanity to Earth's government. Everywhere traces of Dick's impressive imagination, as well as various of his obsessions, are clear -- but nowhere do things cohere, nowhere to they make even the weird sense that Dick made in his better novels.

The Big Jump was first published in the February 1953 issue of Space Stories, and this Ace Double was its first book publication. It is some 42,000 words, and I believe the book and magazine versions are essentially the same. It's a curious sort of book, spending much of its length in Brackett's "hard-boiled" mode, and for that portion its not very successful. But right toward the end it effectively switches to her high-romantic mode, and that brief portion is rather nice.

Arch Comyn is a spaceship construction worker. He hears that somebody has completed "the Big Jump" -- travelled to another star. He learns that his close friend Paul Rogers was on the crew. However, details about the expedition have been suppressed. Comyn hears a rumor that the survivors are hidden in a hospital on Mars owned by the Cochrane Company (which built the spaceship involved). Comyn makes his way to Mars and rather implausibly barges into the Cochrane complex, and finds the hospital room with the one survivor, Captain Ballantyne. Ballantyne is dying, but Comyn hears him say just a bit -- a hint about "transuranics". Then Ballantyne dies, and Comyn is in the custody of the Cochrane Company, who try to beat his secret out of him. Eventually they let him go, and he heads back to Earth, concerned that the secret of what Ballantyne found on a planet of Barnard's Star will be of altogether too much interest to several parties. And indeed, Comyn detects a tail -- but then he sees Cochrane heiress Sydna Cochrane on TV, making a toast to Ballantyne and hinting that a visit from Comyn would be welcome.

Soon Comyn is confronting Sydna, though not before shaking two separate tails, one of whom tries to kill him. Sydna, who is 100% pure Lauren Bacall (remember, this is Brackett in her "tough guy thriller" mode), convinces Comyn to follow her to the Cochrane complex on Luna. Once there, Comyn to his horror sees what's left of Ballantyne -- even though he is dead, his body somehow still lives mindlessly. Before long, he is a) having an affair with Sydna, and b) pushing to join the second expedition to Barnard's Star. After some more hijinks (another assassination attempt), Comyn and a few Cochranes (and some redshirts) are on their way to Barnard's Star. One of the "Cochranes" is William Stanley, a weaselly cousin-by-marriage who lusts after Sydna despite his married state. Stanley reveals that he has stolen the lost logs of the Ballantyne expedition, and he uses this vital knowledge to negotiate controlling interest in the prospective Transuranic company.

Then they arrive at Barnard's Star, and the novel changes tone entirely, to something transcendental, much more reminiscent of the best of Brackett's planetary romances. The other members of the first expedition are found, living in a primitive state with the presumptive natives of the planet. (Natives who seem to be fully humanoid for no reason at all!) Comyn finds his friend Paul Rogers, who refuses to return to Earth. It seems that beings called the Transuranae, composed of transuranic elements, have conferred immortality and freedom from conflict and want on the inhabitants of this planet. So once again we confront the choice -- intellect, striving, knowledge vs. bliss and contentment. (Cf. countless other SF stories, such as "The Milk of Paradise" by Tiptree.) It's no surprise what Comyn chooses (or has chosen for him), but Brackett presents the alternatives in her most evocative style, and really this final section is quite effective.

It's not one of Brackett's best works, but in the end it's decent stuff. The first part, however, is full of plot holes and implausibilities. As well as plain silly stuff like the horror everyone feels at seeing the quasi-living Ballantyne -- still twitching after his death. Spooky, maybe, but not the stuff of Lovecraftian horror as Brackett would have us believe.

a review by Rich Horton

|

| (Covers by Ed Valigursky and Robert E. Schulz) |

It is a pretty significant book for an Ace Double -- two major writers, each of who would surely have been a Grand Master had they not died too soon. Each have writing credits on major SF movies, Dick of course for the original novel behind Blade Runner (and for quite a few other films of varying quality), and Brackett for the first version of the screenplay of The Empire Strikes Back. They are very different writers, but each very important in their own way.

Solar Lottery was Philip Dick's first novel, and this 1955 Ace Double was its first edition. (There was a UK hardcover a year later retitled World of Chance.) It seems to be reasonably well regarded but I must say I found it a mess. It's set in a future in which the leader of the Solar System is chosen by lottery. The current leader, Quizmaster Verrick, has held the position for 10 years, even though assassins are selected by lot to try to kill him. Most of society is controlled by corporations that rate people, theoretically according to their abilities. People swear allegiance to individuals or corporations. As the novel opens, Ted Benteley is at last able to legally escape his allegiance to his corporation, and he travels to Batavia (now Djakarta, of course) in Indonesia, seat of the government, to try to work for the Quizmaster. Unbeknownst to him, however, a new Quizmaster has just been selected, an "unclassified" named Leon Cartwright. Benteley is fooled into swearing direct allegiance to the old Quizmaster.

Cartwright has long been a Prestonite, devotee of the mad theories of John Preston, who believed in a tenth planet beyond Pluto called Flame Disc. Cartwright has just supervised the launch of a spaceship intended to reach Flame Disc, and his only hope of his new Quizmaster position is to buy time for the ship to reach Flame Disc before Solar authorities stop it. As soon as he becomes Quizmaster, Verrick sets in place a plan to fix the lottery for the assassin, and to use a remote controlled android as the next assassin. This, along with a clever scheme to sequentially control the android with different people, will allow his assassin to evade the telepathic protectors of the Quizmaster.

So it's kind of a wild, uncontrolled, mix of elements, some clever, some interesting, some just loony. The plot sort of reels along, as Ted is shanghaied to being one of the assassin's controllers, and also as he fools around with an ex-telepath girl now working for Verrick, while his true destiny, natch, is to work with Cartwright and become the next Quizmaster, hopefully in so doing restoring sanity to Earth's government. Everywhere traces of Dick's impressive imagination, as well as various of his obsessions, are clear -- but nowhere do things cohere, nowhere to they make even the weird sense that Dick made in his better novels.

The Big Jump was first published in the February 1953 issue of Space Stories, and this Ace Double was its first book publication. It is some 42,000 words, and I believe the book and magazine versions are essentially the same. It's a curious sort of book, spending much of its length in Brackett's "hard-boiled" mode, and for that portion its not very successful. But right toward the end it effectively switches to her high-romantic mode, and that brief portion is rather nice.

Arch Comyn is a spaceship construction worker. He hears that somebody has completed "the Big Jump" -- travelled to another star. He learns that his close friend Paul Rogers was on the crew. However, details about the expedition have been suppressed. Comyn hears a rumor that the survivors are hidden in a hospital on Mars owned by the Cochrane Company (which built the spaceship involved). Comyn makes his way to Mars and rather implausibly barges into the Cochrane complex, and finds the hospital room with the one survivor, Captain Ballantyne. Ballantyne is dying, but Comyn hears him say just a bit -- a hint about "transuranics". Then Ballantyne dies, and Comyn is in the custody of the Cochrane Company, who try to beat his secret out of him. Eventually they let him go, and he heads back to Earth, concerned that the secret of what Ballantyne found on a planet of Barnard's Star will be of altogether too much interest to several parties. And indeed, Comyn detects a tail -- but then he sees Cochrane heiress Sydna Cochrane on TV, making a toast to Ballantyne and hinting that a visit from Comyn would be welcome.

Soon Comyn is confronting Sydna, though not before shaking two separate tails, one of whom tries to kill him. Sydna, who is 100% pure Lauren Bacall (remember, this is Brackett in her "tough guy thriller" mode), convinces Comyn to follow her to the Cochrane complex on Luna. Once there, Comyn to his horror sees what's left of Ballantyne -- even though he is dead, his body somehow still lives mindlessly. Before long, he is a) having an affair with Sydna, and b) pushing to join the second expedition to Barnard's Star. After some more hijinks (another assassination attempt), Comyn and a few Cochranes (and some redshirts) are on their way to Barnard's Star. One of the "Cochranes" is William Stanley, a weaselly cousin-by-marriage who lusts after Sydna despite his married state. Stanley reveals that he has stolen the lost logs of the Ballantyne expedition, and he uses this vital knowledge to negotiate controlling interest in the prospective Transuranic company.

Then they arrive at Barnard's Star, and the novel changes tone entirely, to something transcendental, much more reminiscent of the best of Brackett's planetary romances. The other members of the first expedition are found, living in a primitive state with the presumptive natives of the planet. (Natives who seem to be fully humanoid for no reason at all!) Comyn finds his friend Paul Rogers, who refuses to return to Earth. It seems that beings called the Transuranae, composed of transuranic elements, have conferred immortality and freedom from conflict and want on the inhabitants of this planet. So once again we confront the choice -- intellect, striving, knowledge vs. bliss and contentment. (Cf. countless other SF stories, such as "The Milk of Paradise" by Tiptree.) It's no surprise what Comyn chooses (or has chosen for him), but Brackett presents the alternatives in her most evocative style, and really this final section is quite effective.

It's not one of Brackett's best works, but in the end it's decent stuff. The first part, however, is full of plot holes and implausibilities. As well as plain silly stuff like the horror everyone feels at seeing the quasi-living Ballantyne -- still twitching after his death. Spooky, maybe, but not the stuff of Lovecraftian horror as Brackett would have us believe.

Saturday, October 26, 2019

In Memoriam, Michael Blumlein

Rudy Rucker has reported that Michael Blumlein has died, aged 71. I didn't know Blumlein, though I reprinted his exceptional 2012 story "Twenty-Two and You" in The Year's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy: 2013 Edition. But I have been intrigued by his work since discovering his 1986 story, "The Brains of Rats". (We reprinted "The Brains of Rats" at Lightspeed here.) So I will memorialize him in the way I have: by remembering his stories, via things I've written about them, for Locus and for my pre-Locus SFF Net newsgroup.

Also, he has a new novel, or long novella, out this year from Tor.com. It's called Longer, and I missed it earlier but will get it it now.

F&SF Summary, 2000

"Fidelity: a Primer" (September) just struck me as charming and somehow "true". I really liked it. I think as things stand now it's my favorite novelette of the year,

And the following, from a discussion about the definition of SF:

[Gordon van Gelder here brings up "Fidelity: a Primer", a Michael Blumlein F&SF story from 2000, one of my favorite stories of that year. The story is at best only barely SF (I thought is was, but I agree that you could read it differently). But, Gordon suggests, it is important to the success of the story that the reader suspect that it might turn out to be SF. I.e., the venue affects reader expectations, and thus affects the typical reading of the story, possibly in important ways. Interesting, though I admit to being made uneasy by the implication that "Fidelity: a Primer" would be a lesser story if published in the New Yorker.]

2001 Recommended Reading

And Michael Blumlein's "Know How, Can Do" (F&SF, December) combines some clever wordplay -- clever but also thematically meaningful -- with a quite original story about a real scientific idea with real consequences, and real, if decidedly odd, characters facing loss.

Locus, July 2008

The cover story for F&SF in July is a novella from the always interesting Michael Blumlein. “The Roberts” concerns a brilliant architect whose workaholic ways lay waste to his love life. He hits upon a creepy solution – designing his own lover – but this too has pitfalls. It’s a nice story, but a bit too obvious in its working out, and it lacks the shocking originality that characterizes Blumlein’s best work.

Flurb Summary, 2008

My favorite story was Michael Blumlein's "The Big One" (#6), only barely fantastical, indeed almost Carveresque at times, about four men who knew each other in high school fishing much later in life, with lots of, well, life issues impending.

Locus, March 2012

Also first-rate is “Twenty-Two and You”, by Michael Blumlein (F&SF, March-April), which quite plausibly addresses the idea of genetic fixes for inherited diseases. Here a young couple wants to have children, but family history suggests that pregnancy might be very risky for the wife. So she has her genome sequenced, and learns the bad news. But it is possible in this near future to change your genome … but the genome is a complicated thing. This is a nice example of a story with no villains, indeed no fools, but still sadness. An excellent piece of pure science fiction in the sense that it closely examines the effects of scientific change on real people.

Locus, January 2014

Just one magazine to cover this month, the last F&SF of 2013. The longest story is “Success”, by Michael Blumlein, one of our most interesting and original writers. Alas, this story, about a brilliant scientist who goes, it seems mad, never really came to life for me. Dr. Jim, the central character, is cured, after a fashion, and marries again, a long-suffering woman, also an academic. He is working on his life's work, a book about the gene, the epigene, and the paragene, while she is pursuing tenure in a more ordinary fashion. Dr. Jim also battles something, or someone, mysterious in the basement, and becomes obsessed with building something in the backyard, to his wife's eventual disgust … leading to a reversal of fortunes, perhaps … Blumlein is never uninteresting, but as I aid, here he doesn't really – forgive me – succeed.

Also, he has a new novel, or long novella, out this year from Tor.com. It's called Longer, and I missed it earlier but will get it it now.

F&SF Summary, 2000

"Fidelity: a Primer" (September) just struck me as charming and somehow "true". I really liked it. I think as things stand now it's my favorite novelette of the year,

And the following, from a discussion about the definition of SF:

[Gordon van Gelder here brings up "Fidelity: a Primer", a Michael Blumlein F&SF story from 2000, one of my favorite stories of that year. The story is at best only barely SF (I thought is was, but I agree that you could read it differently). But, Gordon suggests, it is important to the success of the story that the reader suspect that it might turn out to be SF. I.e., the venue affects reader expectations, and thus affects the typical reading of the story, possibly in important ways. Interesting, though I admit to being made uneasy by the implication that "Fidelity: a Primer" would be a lesser story if published in the New Yorker.]

2001 Recommended Reading

And Michael Blumlein's "Know How, Can Do" (F&SF, December) combines some clever wordplay -- clever but also thematically meaningful -- with a quite original story about a real scientific idea with real consequences, and real, if decidedly odd, characters facing loss.

Locus, July 2008

The cover story for F&SF in July is a novella from the always interesting Michael Blumlein. “The Roberts” concerns a brilliant architect whose workaholic ways lay waste to his love life. He hits upon a creepy solution – designing his own lover – but this too has pitfalls. It’s a nice story, but a bit too obvious in its working out, and it lacks the shocking originality that characterizes Blumlein’s best work.

Flurb Summary, 2008

My favorite story was Michael Blumlein's "The Big One" (#6), only barely fantastical, indeed almost Carveresque at times, about four men who knew each other in high school fishing much later in life, with lots of, well, life issues impending.

Locus, March 2012

Also first-rate is “Twenty-Two and You”, by Michael Blumlein (F&SF, March-April), which quite plausibly addresses the idea of genetic fixes for inherited diseases. Here a young couple wants to have children, but family history suggests that pregnancy might be very risky for the wife. So she has her genome sequenced, and learns the bad news. But it is possible in this near future to change your genome … but the genome is a complicated thing. This is a nice example of a story with no villains, indeed no fools, but still sadness. An excellent piece of pure science fiction in the sense that it closely examines the effects of scientific change on real people.

Locus, January 2014

Just one magazine to cover this month, the last F&SF of 2013. The longest story is “Success”, by Michael Blumlein, one of our most interesting and original writers. Alas, this story, about a brilliant scientist who goes, it seems mad, never really came to life for me. Dr. Jim, the central character, is cured, after a fashion, and marries again, a long-suffering woman, also an academic. He is working on his life's work, a book about the gene, the epigene, and the paragene, while she is pursuing tenure in a more ordinary fashion. Dr. Jim also battles something, or someone, mysterious in the basement, and becomes obsessed with building something in the backyard, to his wife's eventual disgust … leading to a reversal of fortunes, perhaps … Blumlein is never uninteresting, but as I aid, here he doesn't really – forgive me – succeed.

Thursday, October 24, 2019

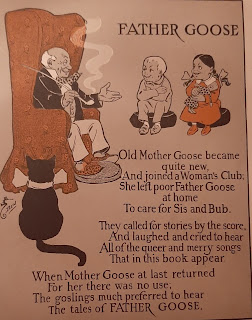

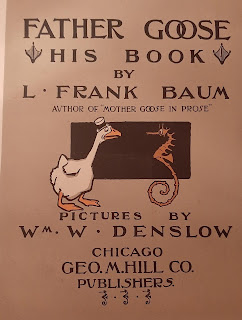

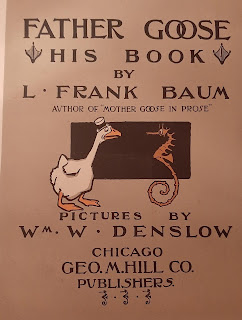

Old Bestseller: Father Goose: His Book, by L. Frank Baum

Old Besteller: Father Goose: His Book, by L. Frank Baum, illustrated by W. W. Denslow

a review by Rich Horton

I found this book at an estate sale, and it looked intriguing. Turns out nice copies are very valuable. My copy isn't exactly nice, but it's in tolerable shape for a book from 1899. It was definitely a bestseller, a major one, I think. My copy was the third printing, 15000 copies, in November 1899. The first edition (September 1899) was 5700 copies, the second, in October, was 10,000 copies.

You all know Lyman Frank Baum, I trust. He was born in 1856 and died in 1919. His early adult life was financially rather a mess, with a series of not terribly successful ventures in poultry breeding, acting, and sales. He moved from New York to South Dakota (which became, more or less, the Kansas of The Wizard of Oz) then to Chicago. While in Chicago he published a children's book called Mother Goose in Prose (1897), illustrated by Maxwell Parrish(!), that was fairly successful. This led to the book at hand, Father Goose, which was the bestselling children's book of 1899. And in 1900 he published The Wizard of Oz, and we know where that went! (Though, despite its enormous success, Baum's financial incompetence, and his grandiose theatrical plans, led to later money problems.) W. W. Denslow, the illustrator of Father Goose, also illustrated (and shared copyright in) the first couple of Oz books, which led to a nasty breakup when they quarreled over credit.

Baum, anyway, eventually found his way to California. He wrote about 16 Oz books and several other fantasies. He was involved in multiple musical productions of Oz related work, and some plays, and early movies, often to his financial detriment. He also reputedly designed parts of the Hotel Del Coronado, on an island near San Diego. After his death, other authors, most notably Ruth Plumly Thompson, continued the Oz series.

(For what it's worth -- fairly little -- I worked with a guy name Francis Baum for a while a number of years ago. He seemed nonplussed by allusions to Oz.)

As for Father Goose: His Book? Well, what it purports to be is "modern" verses in the style of the Mother Goose rhymes. Is it successful? To my ears, not really. The poems seem mostly a bit labored, and the conceits not terribly interesting. Part of the problem is some horribly racist bits -- the piece about the n-word boy is all but impossible to read today, and the stories about Chinamen and the Irish aren't much better. But if we ascribe those to not exactly hostile, just insensitive, views of the time the book was written, still, the poems just aren't much fun. That's not entirely fair -- one in three, maybe, are kind of cute. But never, really, lasting. The Mother Goose rhymes endure -- and deservedly so. And these are forgotten -- deservedly so too, I'd say.

As for Father Goose: His Book? Well, what it purports to be is "modern" verses in the style of the Mother Goose rhymes. Is it successful? To my ears, not really. The poems seem mostly a bit labored, and the conceits not terribly interesting. Part of the problem is some horribly racist bits -- the piece about the n-word boy is all but impossible to read today, and the stories about Chinamen and the Irish aren't much better. But if we ascribe those to not exactly hostile, just insensitive, views of the time the book was written, still, the poems just aren't much fun. That's not entirely fair -- one in three, maybe, are kind of cute. But never, really, lasting. The Mother Goose rhymes endure -- and deservedly so. And these are forgotten -- deservedly so too, I'd say.

(But for all that, The Wizard of Oz is remembered, and absolutely deservedly so!)

Finally, I must mention the pictures, by W. W. Denslow. And these really are quite nice. As noted above, the original Oz illustrations were also by Denslow, and they are very fine as well. Finally, I should mention that this book is hand-lettered, quite well, by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

Finally, I must mention the pictures, by W. W. Denslow. And these really are quite nice. As noted above, the original Oz illustrations were also by Denslow, and they are very fine as well. Finally, I should mention that this book is hand-lettered, quite well, by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

a review by Rich Horton

I found this book at an estate sale, and it looked intriguing. Turns out nice copies are very valuable. My copy isn't exactly nice, but it's in tolerable shape for a book from 1899. It was definitely a bestseller, a major one, I think. My copy was the third printing, 15000 copies, in November 1899. The first edition (September 1899) was 5700 copies, the second, in October, was 10,000 copies.

You all know Lyman Frank Baum, I trust. He was born in 1856 and died in 1919. His early adult life was financially rather a mess, with a series of not terribly successful ventures in poultry breeding, acting, and sales. He moved from New York to South Dakota (which became, more or less, the Kansas of The Wizard of Oz) then to Chicago. While in Chicago he published a children's book called Mother Goose in Prose (1897), illustrated by Maxwell Parrish(!), that was fairly successful. This led to the book at hand, Father Goose, which was the bestselling children's book of 1899. And in 1900 he published The Wizard of Oz, and we know where that went! (Though, despite its enormous success, Baum's financial incompetence, and his grandiose theatrical plans, led to later money problems.) W. W. Denslow, the illustrator of Father Goose, also illustrated (and shared copyright in) the first couple of Oz books, which led to a nasty breakup when they quarreled over credit.

Baum, anyway, eventually found his way to California. He wrote about 16 Oz books and several other fantasies. He was involved in multiple musical productions of Oz related work, and some plays, and early movies, often to his financial detriment. He also reputedly designed parts of the Hotel Del Coronado, on an island near San Diego. After his death, other authors, most notably Ruth Plumly Thompson, continued the Oz series.

(For what it's worth -- fairly little -- I worked with a guy name Francis Baum for a while a number of years ago. He seemed nonplussed by allusions to Oz.)

As for Father Goose: His Book? Well, what it purports to be is "modern" verses in the style of the Mother Goose rhymes. Is it successful? To my ears, not really. The poems seem mostly a bit labored, and the conceits not terribly interesting. Part of the problem is some horribly racist bits -- the piece about the n-word boy is all but impossible to read today, and the stories about Chinamen and the Irish aren't much better. But if we ascribe those to not exactly hostile, just insensitive, views of the time the book was written, still, the poems just aren't much fun. That's not entirely fair -- one in three, maybe, are kind of cute. But never, really, lasting. The Mother Goose rhymes endure -- and deservedly so. And these are forgotten -- deservedly so too, I'd say.

As for Father Goose: His Book? Well, what it purports to be is "modern" verses in the style of the Mother Goose rhymes. Is it successful? To my ears, not really. The poems seem mostly a bit labored, and the conceits not terribly interesting. Part of the problem is some horribly racist bits -- the piece about the n-word boy is all but impossible to read today, and the stories about Chinamen and the Irish aren't much better. But if we ascribe those to not exactly hostile, just insensitive, views of the time the book was written, still, the poems just aren't much fun. That's not entirely fair -- one in three, maybe, are kind of cute. But never, really, lasting. The Mother Goose rhymes endure -- and deservedly so. And these are forgotten -- deservedly so too, I'd say.(But for all that, The Wizard of Oz is remembered, and absolutely deservedly so!)

Finally, I must mention the pictures, by W. W. Denslow. And these really are quite nice. As noted above, the original Oz illustrations were also by Denslow, and they are very fine as well. Finally, I should mention that this book is hand-lettered, quite well, by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

Finally, I must mention the pictures, by W. W. Denslow. And these really are quite nice. As noted above, the original Oz illustrations were also by Denslow, and they are very fine as well. Finally, I should mention that this book is hand-lettered, quite well, by Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)