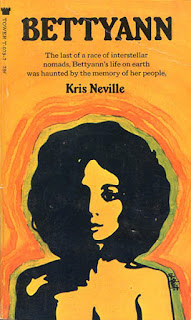

Kris Neville (1925-1980) had one of the interesting disappointing careers in the field. He was a native of Carthage, MO, home of Belle Starr and the great baseball pitcher Carl Hubbell and the far from great (indeed criminal) Missouri Attorney General William Webster, but NOT related to "North Carthage", the fictional town where Gillian Flynn's bestseller Gone Girl is set. (Carthage is near Joplin, entirely across the state from the Mississippi, on which North Carthage is said to sit.)) Thus Neville is the second Missourian in a row I've covered. He lived most of his adult life in California, and began publishing short fiction in 1949, and quickly made an impact, most notably with "Bettyann" (1951), but also "Hunt the Hunter" (1951) and "The Toy" (1952) among others. He also published perhaps a half-dozen novels, the last of which, Run, the Spearmaker, has only been published in Japan, except for an excerpt in the Riverside Quarterly. (It was co-written with his wife Lil, as were other late stories.) The novels were mostly expansions or fixups of earlier stories, and made little impact.

There is little question that he could have had a significant career. Why didn't he? Barry Malzberg, who collaborated with him on two stories and carried on an extensive correspondence, says that this was partly due to frustrated ambition -- the field, perhaps most of all its editors, were not ready to publish work of the ambition he desired. Another reason could be that he had a very good job, a technical writer and an expert on epoxies, which he seems to have liked and in which he was highly respected. Sometimes we readers forget that much as we want to see promising writers keep at it, there are other, equally rewarding, careers, and it's not our call what a given person chooses to do with their life. (I think of P. J. Plauger sometimes in this context.)

Astounding, March 1951

"Casting Office", by "Henderson Starke" (Kris Neville) is set just where it says -- in a casting office. The Actors seem pretty upset with the latest play, and the Critics are hammering it. The Author is peeved. It doesn't take long to figure out what's really going on, and what the "play" really is. Campbell calls it a fantasy, kind of by way of apology to Astounding's readers. There are some cute bits, but it goes on a bit long, and the central twist idea is so clear from the start that I think the story spends too much time acting like the reader can't guess.

Galaxy, June 1951

"Hunt the Hunter" is set on a distant planet where the leader of the human race (I assume) is hunting the mysterious "farn beast". He has roped in as guides two businessmen who have apparently previously visited the planet and bagged a farn beast. Meanwhile, an alien force is supposed to be nosing around the planet. The main viewpoint characters are the two businessmen, who make their resentment of the leader clear -- and who feel even worse when the leader decides to use one of them as bait. The bulk is the story is fairly familiar cynical comedy about bad and worse people variously bumbling around and mistreating each other ... and then the ending, quite literally, springs a little trap. Nice story, not a classic but solid work.

Avon Science Fiction and Fantasy Reader, April 1953

"As Holy and Enchanted" is another story Kris Neville wrote under the name "Henderson Starke". A lonely, ordinary, man name Nick likes to walk in the part on Sundays, representing a more peaceful and natural break from his usual life in the city and work in a shop (perhaps a machine shop?) One Sunday at a fountain he happens across lovely girl name Mona, who seems enchanted by him, and they spend the day together, eating at restaurants and such. Nick falls for her immediately, and she seems intrigued by him -- but the reader, of course, knows right away what sort of creature (or spirit) she is, so the ending is never in doubt. A nicely done bittersweet piece.

(This story appears, of course, on my list of stories with titles taken from "Kubla Khan".)

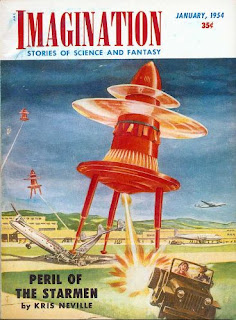

Imagination, January 1954

The cover story (illustrated rather garishly by W. E. Terry) is "Peril of the Starmen", by Kris Neville. Earth is visited by aliens, and we (the readers) learn immediately that their plan is to blow up the planet. (Apparently they subscribe to the logic that I think I saw stated in Charles Pellegrino and George Zebrowski's The Killing Star -- once a species is capable of space flight they are a potential danger, so the smart thing to do is destroy them first.) Of course, the aliens' message is one of peace. One of the aliens, however, begins to have doubts. Set against the aliens' plans is conflict in the US government. Some are eager to welcome the aliens, but another faction, led by a Senator from Missouri who might be described in contemporary terms as "Trumpian", wants nothing to do with the aliens. In essence, they are right, but for totally wrong reasons. The premise is intriguing, but the story goes on a bit too long, mostly turning on an implausible love story between the doubtful alien and the Senator's sister.

9 Tales of Space and Time, 1954

"Overture" is the direct sequel to "Bettyann". (The two stories were combined, presumably with additional material, into a novel in 1970, and another story, "Bettyann's Children", written with Lil Neville, appeared in 1973.) (Obviously, spoilers for "Bettyann" follow.) The story opens with Bettyann, having left the ship in which her alien relatives were planning to take her away, using her shapechanging ability to fly back to her true home, in Southwest Missouri. She must now come to terms with her newly revealed alien abilities, and somehow explain to her parents why she suddenly left Smith College. She becomes obsessed with the idea of making a difference -- perhaps by using her powers to heal people, and she also begins to fall for the much older local doctor. Not much else really happens -- a couple of minor health crises, her young love, her relationship with her adoptive parents -- but the story is very nicely told, sweet, well-written.

Galaxy, October 1968

Kris Neville's "Thyre Planet" is a bit more serious, if not entirely so. The story has two foci, and I'm not sure they work together. On the one hand it's a fairly broad satire of the executive personality, almost Dilbertian in spots, as Mr. Bellflower, a very well-trained expert executive, is hired by Thyre planet to solve the reliability problem with their transport booths, which were left by the natives of Thyre, who have all disappeared. So Bellflower's strategies are shown, which proved to be more based on establishing a power base and keeping the money flowing than actually solving the problem. Thus, a solution to the problem is the worst thing that could happen -- despite the fact that thousands of people a year are lost in the transport booths. The other focus is of course the problem -- and its solution, which is fairly clever, if, I think easily guessable. I liked both aspects of the story, but they seem to sit a little uneasily together.

F&SF, December 1970

"The Reality Machine", by Kris Neville, is a brief, dark, satire that follows an advisor to the President as he tries to brief him on the progress of the title machine, which we eventually learn, really is altering reality. The story seems darkly prescient in presenting an advisor who despite some apparent competence defers entirely to his worthless President; and a President who is happy to deny reality. How did Neville know?

Universe 3, 1974

Kris Neville's "Survival Problems" is, somewhat like "The Reality Machine", a dark satire on American politics. It mainly follows a successful scientist at a Mortuary institute, an expert in preserving people after their death, who wins a lottery to get life extension (at the cost of slowing one's brain processes so they become very stupid.) But first he must deal with crises at his job ... and then it becomes necessary to preserve the President himself ... the story runs on long enough to make the mordant points it wants to make, without really developing a plot -- which is OK, I suppose, because Neville doesn what he wants in its space.

Imagination, January 1954

|

| (Cover by W. E. Terry) |

9 Tales of Space and Time, 1954

|

| (Cover by W. Thut) |

Galaxy, October 1968

Kris Neville's "Thyre Planet" is a bit more serious, if not entirely so. The story has two foci, and I'm not sure they work together. On the one hand it's a fairly broad satire of the executive personality, almost Dilbertian in spots, as Mr. Bellflower, a very well-trained expert executive, is hired by Thyre planet to solve the reliability problem with their transport booths, which were left by the natives of Thyre, who have all disappeared. So Bellflower's strategies are shown, which proved to be more based on establishing a power base and keeping the money flowing than actually solving the problem. Thus, a solution to the problem is the worst thing that could happen -- despite the fact that thousands of people a year are lost in the transport booths. The other focus is of course the problem -- and its solution, which is fairly clever, if, I think easily guessable. I liked both aspects of the story, but they seem to sit a little uneasily together.

F&SF, December 1970

"The Reality Machine", by Kris Neville, is a brief, dark, satire that follows an advisor to the President as he tries to brief him on the progress of the title machine, which we eventually learn, really is altering reality. The story seems darkly prescient in presenting an advisor who despite some apparent competence defers entirely to his worthless President; and a President who is happy to deny reality. How did Neville know?

Universe 3, 1974

Kris Neville's "Survival Problems" is, somewhat like "The Reality Machine", a dark satire on American politics. It mainly follows a successful scientist at a Mortuary institute, an expert in preserving people after their death, who wins a lottery to get life extension (at the cost of slowing one's brain processes so they become very stupid.) But first he must deal with crises at his job ... and then it becomes necessary to preserve the President himself ... the story runs on long enough to make the mordant points it wants to make, without really developing a plot -- which is OK, I suppose, because Neville doesn what he wants in its space.