Stories with Titles Taken from "Kubla Khan"

Many years ago on Usenet I put together (with help from other denizens of the great newsgroup rec.arts.sf.written) a list of stories which take their titles from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem "Kubla Khan". I believe this may be the poem (or, at least, relatively short poem) which has inspired the titles of more SF stories than any other. That list was on my old home page for a while, but has not been anywhere but on my hard drive since the demise of my old host, SFF.net. So I've decided to resurrect it here, just for fun. I've added a few new stories.

The list doesn't include a couple of ambiguous cases -- stories called "Demon Lover", for instance, nor one called "Floating Hair". It does include a couple instances where the story's title isn't a direct quote from the poem, but is clearly directly inspired by the poem. Also, the Raymond F. Jones story listed gets its title from Coleridge's preface to the poem discussing its origin, and why it's not "complete" (N.B.: I think it's plenty "complete", and that the Person from Porlock perhaps did us all a favor!) There are four based on "Down to a Sunless Sea", three called "Ancestral Voices", and two each called "In Xanadu" and "The Milk of Paradise". Doubtless there are some I have missed.

I've read several of these, and those I've read I've bolded.

Chris Amies, "Down to a Sunless Sea", 1994

Ray Bradbury, "A Miracle of Rare Device", 1962

Marion Zimmer Bradley, "Measureless to Man", 1962, Probably better known as "The Dark Intruder".

Thomas M. Disch, "In Xanadu", 2001, A fine story with chapter headings also derived from the poem.

Gardner Dozois and Michael Swanwick, "Ancestral Voices", 1998

Malcolm Ferguson, "A Damsel with a Dulcimer", 1948

Sarah Frost, "Her Symphony and Song", 2014

R. Garcia y Robertson, "Into a Sunless Sea", 1994

Theodora Goss, "Singing of Mount Abora", 2008, World Fantasy Award winner and a wonderful story

David Graham, Down to a Sunless Sea, 1981

Rivka Jacobs, "The Milk of Paradise", 1994

Raymond F. Jones, "The Person From Porlock", 1947

Kari Maaren, Weave a Circle Round, 2017

Syne Mitchell, "Stately's Pleasure Dome", 2003

Kris Neville (writing as Henderson Starke), "As Holy and Enchanted", 1953

Kevin O'Donnell, Jr., "In Xanadu", 1976

Nat Schachner, "Ancestral Voices", 1933

S. M. Stirling, "Ancestral Voices", 1994

Cordwainer Smith, "Down to a Sunless Sea", 1975, This story was completed by Paul Linebarger's wife Genevieve Linebarger.

Brad Strickland, "Beneath a Waning Moon", 1993

Melanie Tem, "Woman Wailing" (poem), 2004

James Tiptree, Jr., "The Milk of Paradise", 1972, A great story, my favorite of this list

Stewart von Allmen, "He on Honeydew", 1995,

Saturday, August 1, 2020

Monday, July 27, 2020

Birthday Review: Stories of Marissa Lingen

I'm a bit late again, but here's a Birthday Review for Marissa Lingen, a number of my reviews of her stories -- work I've liked consistently from her earliest publications, and which seems to have gotten stronger and stronger in recent years.

Locus, February 2005

The Canadian magazine Challenging Destiny has gone to electronic publication, through Fictionwise. I can't but regret this (though I can certainly understand the economic rationale). The words of the stories are the same though! The latest issue, #19 (December 2004) is a pretty strong one. Marissa K. Lingen's "Anna's Implants" has an intriguing idea. The colonists on Anna's planet have what seem to be personality constructs of great artists implanted during their teen years. The idea is to foster creativity – but sometimes it leads to madness. And – does it really help truly original art? Anna seems to be a very promising young artist – and her sister begs her not to take the implant. But Anna has a different idea.

Locus, September 2010

I saw a sequence of lush, fascinating, stories at Beneath Ceaseless Skies in July. “The Six Skills of Madame Lumiere”, by Marissa Lingen, is told by one of Madame Lumiere’s protégés, who worked for her in her whorehouse. Naturally, it was more than a whorehouse, and Madame Lumiere had more skills than just as a Madame. In this story a young man comes asking for help for his cousin, a woman with a special talent that has brought the interest of the cruel Rust Lords. The story involves a convincing journey through Faery, an intriguing talent, different villains, and a set of interesting women lead characters – all mixed delightfully.

Locus, January 2011

In Analog’s January/February Double Issue I enjoyed Marissa Lingen’s “Some of Them Closer”, a nicely quiet piece about a woman returning to Earth after decades helping terraform a new colony planet. Between the travel time (plus time dilation) and time spent on the new planet, she is completely out of touch with the people of Earth, but she had also not felt at home on the new planet. Where can she feel at home? And with whom? The answers are familiar, but the story does a fine job getting us there, and a fine job portraying the main character.

Locus, May 2014

In On Spec for Winter 2013/2104 I particularly liked “The Young Necromancer's Guide to Re-Capitation”, by Marissa Lingen and Alec Austin, which is just lots of fun, concerning a boy who collects minions in the form of re-animated fantastical creatures, here trying to recover the stolen head of his latest minion, a dragon.

Locus, March 2015

Marissa Lingen's “Blue Ribbon”, in the March Analog, is a very enjoyable and moving and rather Heinleinesque YA short set in the Oort Cloud. Tereza Pinheiro and her sister have just won a spaceship race but find themselves barred from returning to the station where their parents are: it is in quarantine. The race is sponsored by their 4H club, and there are a lot of other children in spaceships, all of course with no place to go. The problem is how to survive until help can come, how to keep their spirits up (knowing their parents are possibly very sick), and how to deal with sickness if it strikes any of them. This is well and honestly handled … in in the pure Heinlein manner, we also get a glimpse of an intriguing future space-based society. Good stuff.

Locus, July 2018

Analog’s May-June issue includes several intriguing short stories. Marissa Lingen’s “Finding Their Footing” is about a woman and her two children who have divorced their family in the Oort after her husband’s death, and who are moving to Triton to look for a new position, hoping to stop at Callisto to witness a cryovolcano eruption on the way. This is one of several stories Lingen has published about a future society in the Outer System, and they are collectively fascinating in their details about the structure and dynamics of that society. This piece is quiet, a minor work perhaps, but quite enjoyable, and I hope to see many more stories (or a novel) in this milieu.

Locus, August 2018

The purest SF story in the July-August Analog is “Left to Take the Lead”, by Marissa Lingen, another in her extended sequence of pieces set in a heavily populated Solar System. Holly is a woman from the Oort, forced into an indenture after a catastrophe (the subject of an earlier story) cost her family their home. She is working on a farm near Edmonton, with a good Earth family, and a fellow indenture who becomes a friend. The story turns on the struggles of the rest of her family to make enough money to get everyone together again, and Holly’s struggles to adapt to Earth life. (Plus there’s a bit about hockey (Martian hockey), because Marissa Lingen!) This is solid work in what is becoming a really impressive series dealing with very interesting ideas about the social and economic order of this Solar System.

Locus, March 2019

I also liked Marissa Lingen’s “The Thing, With Feathers” (Uncanny, January-February), which is set in a weirdly post-apocalyptic world – a magical apocalypse. Val is a lighthouse keeper on a lake, once a sort of magical doctor, struggling to maintain belief in a possible future. A man comes to her place by the lake, a stranger, asking for her help. The story, quiet, understated, really portrays the blossoming of something that might be friendship, and, maybe, a bit of, well – the thing with feathers.

Locus, December 2019

In the November-December Analog Marissa Lingen contributes a strong well grounded story, “Filaments of Hope”, about Lif, who has been planning to go to Mars as long as they’ve been able to, and who is left at loose ends when the mission in canceled. So they visit relatives in Iceland, and they find, perhaps, that what they’ve learned about adapting to Mars still has meaning on this ever-changing, ever-challenging, world. It’s a quiet story, with no bombshells: just solid and believable characters.

Locus, February 2005

The Canadian magazine Challenging Destiny has gone to electronic publication, through Fictionwise. I can't but regret this (though I can certainly understand the economic rationale). The words of the stories are the same though! The latest issue, #19 (December 2004) is a pretty strong one. Marissa K. Lingen's "Anna's Implants" has an intriguing idea. The colonists on Anna's planet have what seem to be personality constructs of great artists implanted during their teen years. The idea is to foster creativity – but sometimes it leads to madness. And – does it really help truly original art? Anna seems to be a very promising young artist – and her sister begs her not to take the implant. But Anna has a different idea.

Locus, September 2010

I saw a sequence of lush, fascinating, stories at Beneath Ceaseless Skies in July. “The Six Skills of Madame Lumiere”, by Marissa Lingen, is told by one of Madame Lumiere’s protégés, who worked for her in her whorehouse. Naturally, it was more than a whorehouse, and Madame Lumiere had more skills than just as a Madame. In this story a young man comes asking for help for his cousin, a woman with a special talent that has brought the interest of the cruel Rust Lords. The story involves a convincing journey through Faery, an intriguing talent, different villains, and a set of interesting women lead characters – all mixed delightfully.

Locus, January 2011

In Analog’s January/February Double Issue I enjoyed Marissa Lingen’s “Some of Them Closer”, a nicely quiet piece about a woman returning to Earth after decades helping terraform a new colony planet. Between the travel time (plus time dilation) and time spent on the new planet, she is completely out of touch with the people of Earth, but she had also not felt at home on the new planet. Where can she feel at home? And with whom? The answers are familiar, but the story does a fine job getting us there, and a fine job portraying the main character.

Locus, May 2014

In On Spec for Winter 2013/2104 I particularly liked “The Young Necromancer's Guide to Re-Capitation”, by Marissa Lingen and Alec Austin, which is just lots of fun, concerning a boy who collects minions in the form of re-animated fantastical creatures, here trying to recover the stolen head of his latest minion, a dragon.

Locus, March 2015

Marissa Lingen's “Blue Ribbon”, in the March Analog, is a very enjoyable and moving and rather Heinleinesque YA short set in the Oort Cloud. Tereza Pinheiro and her sister have just won a spaceship race but find themselves barred from returning to the station where their parents are: it is in quarantine. The race is sponsored by their 4H club, and there are a lot of other children in spaceships, all of course with no place to go. The problem is how to survive until help can come, how to keep their spirits up (knowing their parents are possibly very sick), and how to deal with sickness if it strikes any of them. This is well and honestly handled … in in the pure Heinlein manner, we also get a glimpse of an intriguing future space-based society. Good stuff.

Locus, July 2018

Analog’s May-June issue includes several intriguing short stories. Marissa Lingen’s “Finding Their Footing” is about a woman and her two children who have divorced their family in the Oort after her husband’s death, and who are moving to Triton to look for a new position, hoping to stop at Callisto to witness a cryovolcano eruption on the way. This is one of several stories Lingen has published about a future society in the Outer System, and they are collectively fascinating in their details about the structure and dynamics of that society. This piece is quiet, a minor work perhaps, but quite enjoyable, and I hope to see many more stories (or a novel) in this milieu.

Locus, August 2018

The purest SF story in the July-August Analog is “Left to Take the Lead”, by Marissa Lingen, another in her extended sequence of pieces set in a heavily populated Solar System. Holly is a woman from the Oort, forced into an indenture after a catastrophe (the subject of an earlier story) cost her family their home. She is working on a farm near Edmonton, with a good Earth family, and a fellow indenture who becomes a friend. The story turns on the struggles of the rest of her family to make enough money to get everyone together again, and Holly’s struggles to adapt to Earth life. (Plus there’s a bit about hockey (Martian hockey), because Marissa Lingen!) This is solid work in what is becoming a really impressive series dealing with very interesting ideas about the social and economic order of this Solar System.

Locus, March 2019

I also liked Marissa Lingen’s “The Thing, With Feathers” (Uncanny, January-February), which is set in a weirdly post-apocalyptic world – a magical apocalypse. Val is a lighthouse keeper on a lake, once a sort of magical doctor, struggling to maintain belief in a possible future. A man comes to her place by the lake, a stranger, asking for her help. The story, quiet, understated, really portrays the blossoming of something that might be friendship, and, maybe, a bit of, well – the thing with feathers.

Locus, December 2019

In the November-December Analog Marissa Lingen contributes a strong well grounded story, “Filaments of Hope”, about Lif, who has been planning to go to Mars as long as they’ve been able to, and who is left at loose ends when the mission in canceled. So they visit relatives in Iceland, and they find, perhaps, that what they’ve learned about adapting to Mars still has meaning on this ever-changing, ever-challenging, world. It’s a quiet story, with no bombshells: just solid and believable characters.

Sunday, July 19, 2020

Birthday Review: Stories of Mercurio D. Rivera

Today is the birthday of Mercurio D. Rivera. He's been publishing short fiction since 2005, always interesting, and increasing in power, I think. At least, his Asimov's story from this year is very impressive. Here's a collection of my reviews of his work from Locus.

Locus, September 2006

“Longing for Langalana”, by Mercurio D. Rivera (Interzone, June), is a sad story of humans colonizing a planet in partnership with an alien species, the Wergen. The aliens have a couple of intriguing features: on marriage they are physically connected, growing ever closer over years. And they are obsessively attracted to humans. But the colonization of Langalana runs into problems (due to a cleverly depicted native species) – and in parallel the relationship of humans and the Wergen deteriorates. This is movingly portrayed by the relationship of the story’s narrator, a Wergen female, with the human boy she meets and is inevitably drawn to as an adolescent.

Locus, April 2008

The first 2008 issue of Abyss and Apex is a good one. Two particularly sharp-edged pieces work best: Mercurio D. Rivera’s “Snatch Me Another” deals with the implications of a technology that can “snatch” conjugate items from parallel universes, and the effect on one mother and her partner, as we slowly realize that they have “snatched” a replacement for their dead child.

Locus, July 2010

I also quite liked Mercurio D. Rivera’s “Dance of the Kawkawroons” (Interzone, March-April), about a couple of rapacious humans coming to the planet of the alien Kawkawroons to try to retrieve an egg with some precious properties. Still, though I enjoyed it, I thought its focus slightly off – the aliens fascinated me, and I’d have liked to learn more.

Locus, October 2011

Mercurio D. Rivera’s stories about the Wergen, an advanced alien race bound by chemistry to obsessively bond to humans, have been consistently interesting, and “For Love’s Delirium Haunts the Fractured Mind” is a particularly strong piece, from the July-August Interzone. Joriander is a Wergen serving a human family on Mars, as something of a guardian/pet for a young boy. He loves this role, but we see, over the length of the story, by observing the way his “owners” act, and by confrontations with his brother, how degrading it is. In the end, one is reminded of Lee’s feelings, that slavery is worse for the owner worse than the slave – and reminded as well that bad as it is, especially morally, for the owner, it really is actually worse for the slave. Even when they are conditioned to love it.

Locus, June 2012

June sees the Asimov's debuts of three newish writers who have been doing strong work for other magazines. None is quite the author's best work, but all three are enjoyable stories. And Mercurio D. Rivera, an Interzone regular, offers “Missionaries”, which has plenty of intriguing elements but doesn't quite close the deal, telling of a religious group coming to try to speak to aliens on a distant planet.

Locus, April 2020

The March-April Asimov’s features Mercurio D. Rivera’s “Beyond the Tattered Veil of Stars”, an impressive story in the lineage of Theodore Sturgeon’s “Microcosmic God”. It’s told in two threads – one follows a series of entries from the chronicles of an alien race, as they deal with a series of catastrophes; and the other is told by a journalist involved with an old friend of his, who has created something remarkable: a virtual simulation of an alternate world; in which she subjects her simulated creatures to horrible crises, in the hope that their ingenuity will create something she can use in our Earth to deal with our problems. The story deals effectively with the ethical issues this raises – and the ethical issues surrounding the journalist’s motives – and also with the reactions of the simulated creatures, leading to a striking and dark (if ambiguously hopeful, but for who?) conclusion.

Locus, September 2006

“Longing for Langalana”, by Mercurio D. Rivera (Interzone, June), is a sad story of humans colonizing a planet in partnership with an alien species, the Wergen. The aliens have a couple of intriguing features: on marriage they are physically connected, growing ever closer over years. And they are obsessively attracted to humans. But the colonization of Langalana runs into problems (due to a cleverly depicted native species) – and in parallel the relationship of humans and the Wergen deteriorates. This is movingly portrayed by the relationship of the story’s narrator, a Wergen female, with the human boy she meets and is inevitably drawn to as an adolescent.

Locus, April 2008

The first 2008 issue of Abyss and Apex is a good one. Two particularly sharp-edged pieces work best: Mercurio D. Rivera’s “Snatch Me Another” deals with the implications of a technology that can “snatch” conjugate items from parallel universes, and the effect on one mother and her partner, as we slowly realize that they have “snatched” a replacement for their dead child.

Locus, July 2010

I also quite liked Mercurio D. Rivera’s “Dance of the Kawkawroons” (Interzone, March-April), about a couple of rapacious humans coming to the planet of the alien Kawkawroons to try to retrieve an egg with some precious properties. Still, though I enjoyed it, I thought its focus slightly off – the aliens fascinated me, and I’d have liked to learn more.

Locus, October 2011

Mercurio D. Rivera’s stories about the Wergen, an advanced alien race bound by chemistry to obsessively bond to humans, have been consistently interesting, and “For Love’s Delirium Haunts the Fractured Mind” is a particularly strong piece, from the July-August Interzone. Joriander is a Wergen serving a human family on Mars, as something of a guardian/pet for a young boy. He loves this role, but we see, over the length of the story, by observing the way his “owners” act, and by confrontations with his brother, how degrading it is. In the end, one is reminded of Lee’s feelings, that slavery is worse for the owner worse than the slave – and reminded as well that bad as it is, especially morally, for the owner, it really is actually worse for the slave. Even when they are conditioned to love it.

Locus, June 2012

June sees the Asimov's debuts of three newish writers who have been doing strong work for other magazines. None is quite the author's best work, but all three are enjoyable stories. And Mercurio D. Rivera, an Interzone regular, offers “Missionaries”, which has plenty of intriguing elements but doesn't quite close the deal, telling of a religious group coming to try to speak to aliens on a distant planet.

Locus, April 2020

The March-April Asimov’s features Mercurio D. Rivera’s “Beyond the Tattered Veil of Stars”, an impressive story in the lineage of Theodore Sturgeon’s “Microcosmic God”. It’s told in two threads – one follows a series of entries from the chronicles of an alien race, as they deal with a series of catastrophes; and the other is told by a journalist involved with an old friend of his, who has created something remarkable: a virtual simulation of an alternate world; in which she subjects her simulated creatures to horrible crises, in the hope that their ingenuity will create something she can use in our Earth to deal with our problems. The story deals effectively with the ethical issues this raises – and the ethical issues surrounding the journalist’s motives – and also with the reactions of the simulated creatures, leading to a striking and dark (if ambiguously hopeful, but for who?) conclusion.

Tuesday, July 7, 2020

Belated Birthday Review: Stories of Leah Cypess

Leah Cypess had a birthday recently, and I prepared this set of reviews of her work I've done for Locus, but life intervened, and I didn't get around to posting it. So -- finally! Happy Birthday, late! I like how these reviews, to me, show a writer, though always interesting, growing and growing.

Locus, September 2013

I wanted to like Leah Cypess' “What We Ourselves Are Not” (Asimov's, September) more than I did, because its central idea is interesting – an implant that gives people access to real memories of people of their culture, with the idea that this will help preserve diverse cultures. Alas, the main characters (two teenagers) don't convince, and the story is given to somewhat loaded arguments for both sides of the (worthwhile) question considered.

Locus, August 2016

Leah Cypess’ “Filtered” (Asimov's, July) concerns a journalist struggling with getting a story he thinks important noticed in a world where online filters tailor what everyone sees so much that nobody sees anything that will challenged their preconceptions. It’s further complicated because his wife is also his boss – and their ambitions, and their slightly different focus, might threaten their marriage.

Locus, June 2017

From the May-June Asimov's, “On the Ship” is another impressive and thoughtful idea piece from Leah Cypess. The narrator is a child on a spaceship searching for a new home planet. (A perhaps too explicit analogy is made with the horrible treatment of the Jewish refugees on the St. Louis before World War II.) Life on the ship seems fairly happy, and every time a new planet is reached there is a party while it is tested. But the narrator soon realizes that something strange is happening, especially when a mysterious woman keeps showing up unexpectedly. The secret isn’t much of a surprise to SF readers, but it’s used and resolved effectively here.

Locus, July 2017

Leah Cypess contributes “Neko Brushes” (F&SF, May-June), an effective retelling of a Japanese folktale about a boy who can paint things so well they come to life – mostly cats, but eventually a magic sword in service to a woman in revolt against the Emperor.

Locus, August 2018

And, finally, don’t miss “Attachment Unavailable” by Leah Cypess (Asimov's, July-August), a short and sharply funny story told as a comment thread from a social media group of new parents, discussing the offer of some aliens to help their babies sleep better.

Locus, April 2019

Leah Cypess, in “Parenting License” (Analog, March-April), takes on the notion that prospective parents might need training before insurance companies will pay for the costs of pregnancy, childbirth, and child rearing. Melanie, thus, is panicked when she turns up pregnant by accident before she and her husband have had gotten their Parenting License. At first blush it seems poised to be a satirical take on the issue, but instead it too looks quite soberly at the problem.

Locus, May 2020

What matters most? Plot? Character? Prose? Something else? The answer is all of the above, I think, and more importantly, each reinforces the other, ideally. These thoughts are prompted by an exceptional novelet in the May-June F&SF, “Stepsister”, by Leah Cypess. At first look, this is as cleverly constructed a plot as I’ve seen in some time. It’s a Cinderella retelling, from the point of view not of a stepsister, but of the Prince’s stepbrother. He’s absolutely loyal to his Prince (now King), partly, to be sure, because any sign of the bastard son of the former King being less than loyal would mean his life. But now the King wants him to fetch Queen Ella’s stepsister from the refuge the King allowed her when Ella insisted her sisters and mother be killed. There’s a tangled mesh of personal issues to deal with – Ella’s hate for her sister is justified: she really was an abuser; however the King had fallen for her just enough to save her life; and the stepbrother – had completely fallen for her. But what now? Does the King want a new Queen, as Ella has proved barren? Has Ella discovered she is still alive, and does she want her killed? What will the stepbrother do? Does the stepsister even have a voice in this?

All these snarled threads are just beautifully resolved. And we realize, that much as this expertly constructed plot snaps shut perfectly, we’ve seen a story of character wonderfully resolved as well – the beautiful plot wouldn’t work if we didn’t believe in the motivations – in the love! – of each of the characters. Even the character we don’t know about until the end. Excellent!

Locus, September 2013

I wanted to like Leah Cypess' “What We Ourselves Are Not” (Asimov's, September) more than I did, because its central idea is interesting – an implant that gives people access to real memories of people of their culture, with the idea that this will help preserve diverse cultures. Alas, the main characters (two teenagers) don't convince, and the story is given to somewhat loaded arguments for both sides of the (worthwhile) question considered.

Locus, August 2016

Leah Cypess’ “Filtered” (Asimov's, July) concerns a journalist struggling with getting a story he thinks important noticed in a world where online filters tailor what everyone sees so much that nobody sees anything that will challenged their preconceptions. It’s further complicated because his wife is also his boss – and their ambitions, and their slightly different focus, might threaten their marriage.

Locus, June 2017

From the May-June Asimov's, “On the Ship” is another impressive and thoughtful idea piece from Leah Cypess. The narrator is a child on a spaceship searching for a new home planet. (A perhaps too explicit analogy is made with the horrible treatment of the Jewish refugees on the St. Louis before World War II.) Life on the ship seems fairly happy, and every time a new planet is reached there is a party while it is tested. But the narrator soon realizes that something strange is happening, especially when a mysterious woman keeps showing up unexpectedly. The secret isn’t much of a surprise to SF readers, but it’s used and resolved effectively here.

Locus, July 2017

Leah Cypess contributes “Neko Brushes” (F&SF, May-June), an effective retelling of a Japanese folktale about a boy who can paint things so well they come to life – mostly cats, but eventually a magic sword in service to a woman in revolt against the Emperor.

Locus, August 2018

And, finally, don’t miss “Attachment Unavailable” by Leah Cypess (Asimov's, July-August), a short and sharply funny story told as a comment thread from a social media group of new parents, discussing the offer of some aliens to help their babies sleep better.

Locus, April 2019

Leah Cypess, in “Parenting License” (Analog, March-April), takes on the notion that prospective parents might need training before insurance companies will pay for the costs of pregnancy, childbirth, and child rearing. Melanie, thus, is panicked when she turns up pregnant by accident before she and her husband have had gotten their Parenting License. At first blush it seems poised to be a satirical take on the issue, but instead it too looks quite soberly at the problem.

Locus, May 2020

What matters most? Plot? Character? Prose? Something else? The answer is all of the above, I think, and more importantly, each reinforces the other, ideally. These thoughts are prompted by an exceptional novelet in the May-June F&SF, “Stepsister”, by Leah Cypess. At first look, this is as cleverly constructed a plot as I’ve seen in some time. It’s a Cinderella retelling, from the point of view not of a stepsister, but of the Prince’s stepbrother. He’s absolutely loyal to his Prince (now King), partly, to be sure, because any sign of the bastard son of the former King being less than loyal would mean his life. But now the King wants him to fetch Queen Ella’s stepsister from the refuge the King allowed her when Ella insisted her sisters and mother be killed. There’s a tangled mesh of personal issues to deal with – Ella’s hate for her sister is justified: she really was an abuser; however the King had fallen for her just enough to save her life; and the stepbrother – had completely fallen for her. But what now? Does the King want a new Queen, as Ella has proved barren? Has Ella discovered she is still alive, and does she want her killed? What will the stepbrother do? Does the stepsister even have a voice in this?

All these snarled threads are just beautifully resolved. And we realize, that much as this expertly constructed plot snaps shut perfectly, we’ve seen a story of character wonderfully resolved as well – the beautiful plot wouldn’t work if we didn’t believe in the motivations – in the love! – of each of the characters. Even the character we don’t know about until the end. Excellent!

Saturday, July 4, 2020

Revised Review: The Other Nineteenth Century, by Avram Davidson

The Other Nineteenth Century, by Avram Davidson

a review by Rich Horton

A little while ago, for Avram Davidson's birthday, I posted a "review" I had done of this book for my blog, almost two decades ago. It was a carelessly tossed-off piece, arguably OK for a blog post (though still wrongheaded as I have found!), but I never should have reposted it.

I got some criticism, gentle and very fair. And I thought, "Rereading Avram Davidson is never a bad thing! Why not reread the book!" And so I have.

To begin with -- stupid things I said in that first review -- for one thing, I complained that not all the stories are really set in the 19th Century. To which the simple answer is, "So what!". In fact, most at least touch on the 19th Century, and those that don't are either from a bit earlier, or at least have a certain redolence of that time about them. (Indeed, if you choose to end the 19th Century not with the calendar's demarcation but instead the beginning of World War I, as some do, just as some end the '50s with Kennedy's assassination, a couple further stories come in, including one which explicitly is placed right at that event.) Second: I bitched about "Mickelrede", a rather strange piece that Michael Swanwick put together from notes Davidson had left for an abandoned novel. On rereading that piece, I wonder what the heck I was thinking when I read it the first time.

Anyway, to the burden of my new review. The Other Nineteenth Century was the third Davidson collection in four years to come from St. Martins or Tor, after The Avram Davidson Treasury and The Investigations of Avram Davidson, so in a sense it was picking through leftovers, especially as all three books mostly skirted his two acclaimed short story series, the Eszterhazy and Limekiller stories. (This book does include a later and rather short Eszterhazy piece, and one story that appeared in the Treasury.) But the richness of Davidson's catalogue is thus revealed -- even with that constraint, and with the thematic constraint of choosing pieces that at least vaguely suggest the 19th Century, the book is worthwhile throughout, and includes a few pieces that stand among his very best stories.

For example, "Dragon Skin Drum", which I prefer to his slightly better known story of post-War China, "Dagon". "Dragon Skin Drum" is told from the viewpoint of an earnest and naive soldier, who visits a restaurant in the Forbidden City in the company of his more rough-edged friend, Gunnery Sergeant Jackson. Howard tries out his knowledge of Chinese, and tries to understand the local guides/interpreters he must hire, and puts up with Jackson's crudeness, and hears the story of the title drum ... and we learn a bit about these two characters (Jackson not surprisingly the savvier), and about this particular time, right as Mao is marching.

Also, "The Montavarde Camera", a really effective biter bit piece about a man who buys a camera from one of those mysterious little shops you can never find again. The camera has a sinister background -- people whose pictures are taken tend to die soon. And the man has a nagging wife ... We see where this is going, and it gets there just right.

Certainly among the best of Davidson's late stories is "El Vilvoy de las Islas". Many have noticed that his style grew more mannered, more prolix, late in his life. Sometimes this habit was taken to excess, but sometimes it worked, as here. The narrator seems to be the author himself, on a trip through South America. Feeling too tired to continue, he stops in a country called Ereguay, and eventually hears the story of "El Vilvoy" -- a young man from the Islas Encantadas, who, visiting the mainland, saves a woman from an attack, and becomes a sensation for a while. It eventuates that he and his family, on a nearly deserted small isle, live a simple life ... but there are mysteries. And so Davidson wanders through various newspaper accounts, oral stories, and so on, letting us piece together the story of the "Wild Boy".

"What Strange Stars and Skies" has been a favorite of mine for a long time -- telling of a Dame Philippa, who does charity work in the slums of London, and when ministering to the poor near a sailor's house, encounters a very curious press gang. The last line is wonderful.

I first encountered "The Man Who Saw the Elephant" in this book, and it delighted and moved me -- it's about a Quaker couple, the wife hardworking and only just tolerant of her husband's dreams ... one of which is to see the elephant that a traveling showman advertises. In the end, the husband does get to see ... well, if not an elephant something quite wonderful anyway, it seems to me.

I don't perhaps have time to discuss every story. Many turn on portraying a reasonably well known historical incident, or set of characters, from a slant -- and letting the reader figure out what's really going on. Davidson also delights in Alternate History, such as "O Brave Old World!", about the radically different history of America had Frederick of Hanover survived and moved to the Colonies; or "Pebble in Time" (with Cynthia Goldstone) in which a Mormon travels back in time to witness Brigham Young reaching the Salt Lake and unexpectedly changes history, leading to a different 1960s in San Francisco (though concluding with a labored pun that doesn't land as easily now as it might have when first published.) The stories are a mix of historical fiction, mystery, and SF/F, from a very wide range of sources. The editors and a couple more people contribute short afterwords, rather a mixed bag -- some add intriguing detail (including, in one case, Davidson's editorial interaction with Robert P. Mills), others, alas, rather clumsily step on the subtle point Davidson is reaching for.

Finally I need to address a quite odd posthumous collaboration that closes the book, "Mickelrede", put together by Michael Swanwick from a set of notes that Davidson left for an unfinished novel begun in the early '60s. In my previous review, I was very dismissive of the story, which I really failed to understand. Honestly, I'm ashamed, because actually it's not that difficult to follow. It helps somewhat to get the context right -- now I can see that the notes really do look like they might plausibly have become a novel very much in the mode Davidson was using for his earliest short novels, such as Masters of the Maze. The novel involves a contemporary academic thrust into another world (possibly the future) to serve in some sort of combat games, and also to deal with the Green King and the holy Mickelrede, a sacred object that seems to be a slide rule. There is a woman involved, of course, and Swanwick advances some alternate plot points, such as changing the slide rule to a Difference Engine, and the woman to Ada Lovelace. Davidson's novels, at this point in his career, were not his best work, and I can imagine well enough the novel which might have resulted, which would have been enjoyable but not great (sort of a better written Ken Bulmer, for those who remember Bulmer) -- the possibility of a later true collaboration between Swanwick and Davidson, incorporating Swanwick's ideas, is intriguing but likely would not have been the best use of either authors talents -- though who knows? The prose in this fragment seems more Swanwick than Davidson, but that's hardly a complaint, and there certainly are hints of Davidson as well.

a review by Rich Horton

A little while ago, for Avram Davidson's birthday, I posted a "review" I had done of this book for my blog, almost two decades ago. It was a carelessly tossed-off piece, arguably OK for a blog post (though still wrongheaded as I have found!), but I never should have reposted it.

I got some criticism, gentle and very fair. And I thought, "Rereading Avram Davidson is never a bad thing! Why not reread the book!" And so I have.

To begin with -- stupid things I said in that first review -- for one thing, I complained that not all the stories are really set in the 19th Century. To which the simple answer is, "So what!". In fact, most at least touch on the 19th Century, and those that don't are either from a bit earlier, or at least have a certain redolence of that time about them. (Indeed, if you choose to end the 19th Century not with the calendar's demarcation but instead the beginning of World War I, as some do, just as some end the '50s with Kennedy's assassination, a couple further stories come in, including one which explicitly is placed right at that event.) Second: I bitched about "Mickelrede", a rather strange piece that Michael Swanwick put together from notes Davidson had left for an abandoned novel. On rereading that piece, I wonder what the heck I was thinking when I read it the first time.

Anyway, to the burden of my new review. The Other Nineteenth Century was the third Davidson collection in four years to come from St. Martins or Tor, after The Avram Davidson Treasury and The Investigations of Avram Davidson, so in a sense it was picking through leftovers, especially as all three books mostly skirted his two acclaimed short story series, the Eszterhazy and Limekiller stories. (This book does include a later and rather short Eszterhazy piece, and one story that appeared in the Treasury.) But the richness of Davidson's catalogue is thus revealed -- even with that constraint, and with the thematic constraint of choosing pieces that at least vaguely suggest the 19th Century, the book is worthwhile throughout, and includes a few pieces that stand among his very best stories.

For example, "Dragon Skin Drum", which I prefer to his slightly better known story of post-War China, "Dagon". "Dragon Skin Drum" is told from the viewpoint of an earnest and naive soldier, who visits a restaurant in the Forbidden City in the company of his more rough-edged friend, Gunnery Sergeant Jackson. Howard tries out his knowledge of Chinese, and tries to understand the local guides/interpreters he must hire, and puts up with Jackson's crudeness, and hears the story of the title drum ... and we learn a bit about these two characters (Jackson not surprisingly the savvier), and about this particular time, right as Mao is marching.

Also, "The Montavarde Camera", a really effective biter bit piece about a man who buys a camera from one of those mysterious little shops you can never find again. The camera has a sinister background -- people whose pictures are taken tend to die soon. And the man has a nagging wife ... We see where this is going, and it gets there just right.

Certainly among the best of Davidson's late stories is "El Vilvoy de las Islas". Many have noticed that his style grew more mannered, more prolix, late in his life. Sometimes this habit was taken to excess, but sometimes it worked, as here. The narrator seems to be the author himself, on a trip through South America. Feeling too tired to continue, he stops in a country called Ereguay, and eventually hears the story of "El Vilvoy" -- a young man from the Islas Encantadas, who, visiting the mainland, saves a woman from an attack, and becomes a sensation for a while. It eventuates that he and his family, on a nearly deserted small isle, live a simple life ... but there are mysteries. And so Davidson wanders through various newspaper accounts, oral stories, and so on, letting us piece together the story of the "Wild Boy".

"What Strange Stars and Skies" has been a favorite of mine for a long time -- telling of a Dame Philippa, who does charity work in the slums of London, and when ministering to the poor near a sailor's house, encounters a very curious press gang. The last line is wonderful.

I first encountered "The Man Who Saw the Elephant" in this book, and it delighted and moved me -- it's about a Quaker couple, the wife hardworking and only just tolerant of her husband's dreams ... one of which is to see the elephant that a traveling showman advertises. In the end, the husband does get to see ... well, if not an elephant something quite wonderful anyway, it seems to me.

I don't perhaps have time to discuss every story. Many turn on portraying a reasonably well known historical incident, or set of characters, from a slant -- and letting the reader figure out what's really going on. Davidson also delights in Alternate History, such as "O Brave Old World!", about the radically different history of America had Frederick of Hanover survived and moved to the Colonies; or "Pebble in Time" (with Cynthia Goldstone) in which a Mormon travels back in time to witness Brigham Young reaching the Salt Lake and unexpectedly changes history, leading to a different 1960s in San Francisco (though concluding with a labored pun that doesn't land as easily now as it might have when first published.) The stories are a mix of historical fiction, mystery, and SF/F, from a very wide range of sources. The editors and a couple more people contribute short afterwords, rather a mixed bag -- some add intriguing detail (including, in one case, Davidson's editorial interaction with Robert P. Mills), others, alas, rather clumsily step on the subtle point Davidson is reaching for.

Finally I need to address a quite odd posthumous collaboration that closes the book, "Mickelrede", put together by Michael Swanwick from a set of notes that Davidson left for an unfinished novel begun in the early '60s. In my previous review, I was very dismissive of the story, which I really failed to understand. Honestly, I'm ashamed, because actually it's not that difficult to follow. It helps somewhat to get the context right -- now I can see that the notes really do look like they might plausibly have become a novel very much in the mode Davidson was using for his earliest short novels, such as Masters of the Maze. The novel involves a contemporary academic thrust into another world (possibly the future) to serve in some sort of combat games, and also to deal with the Green King and the holy Mickelrede, a sacred object that seems to be a slide rule. There is a woman involved, of course, and Swanwick advances some alternate plot points, such as changing the slide rule to a Difference Engine, and the woman to Ada Lovelace. Davidson's novels, at this point in his career, were not his best work, and I can imagine well enough the novel which might have resulted, which would have been enjoyable but not great (sort of a better written Ken Bulmer, for those who remember Bulmer) -- the possibility of a later true collaboration between Swanwick and Davidson, incorporating Swanwick's ideas, is intriguing but likely would not have been the best use of either authors talents -- though who knows? The prose in this fragment seems more Swanwick than Davidson, but that's hardly a complaint, and there certainly are hints of Davidson as well.

Monday, June 22, 2020

Very Belated Birthday Review: Stories of Kris Neville

Here's a very belated birthday review for Kris Neville, born May 9, 1925. I wanted to write about him, but I had only reviewed three or four of his stories, so I dug up a few more and read them ...

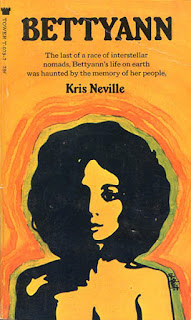

Kris Neville (1925-1980) had one of the interesting disappointing careers in the field. He was a native of Carthage, MO, home of Belle Starr and the great baseball pitcher Carl Hubbell and the far from great (indeed criminal) Missouri Attorney General William Webster, but NOT related to "North Carthage", the fictional town where Gillian Flynn's bestseller Gone Girl is set. (Carthage is near Joplin, entirely across the state from the Mississippi, on which North Carthage is said to sit.)) Thus Neville is the second Missourian in a row I've covered. He lived most of his adult life in California, and began publishing short fiction in 1949, and quickly made an impact, most notably with "Bettyann" (1951), but also "Hunt the Hunter" (1951) and "The Toy" (1952) among others. He also published perhaps a half-dozen novels, the last of which, Run, the Spearmaker, has only been published in Japan, except for an excerpt in the Riverside Quarterly. (It was co-written with his wife Lil, as were other late stories.) The novels were mostly expansions or fixups of earlier stories, and made little impact.

There is little question that he could have had a significant career. Why didn't he? Barry Malzberg, who collaborated with him on two stories and carried on an extensive correspondence, says that this was partly due to frustrated ambition -- the field, perhaps most of all its editors, were not ready to publish work of the ambition he desired. Another reason could be that he had a very good job, a technical writer and an expert on epoxies, which he seems to have liked and in which he was highly respected. Sometimes we readers forget that much as we want to see promising writers keep at it, there are other, equally rewarding, careers, and it's not our call what a given person chooses to do with their life. (I think of P. J. Plauger sometimes in this context.)

Astounding, March 1951

"Casting Office", by "Henderson Starke" (Kris Neville) is set just where it says -- in a casting office. The Actors seem pretty upset with the latest play, and the Critics are hammering it. The Author is peeved. It doesn't take long to figure out what's really going on, and what the "play" really is. Campbell calls it a fantasy, kind of by way of apology to Astounding's readers. There are some cute bits, but it goes on a bit long, and the central twist idea is so clear from the start that I think the story spends too much time acting like the reader can't guess.

Galaxy, June 1951

"Hunt the Hunter" is set on a distant planet where the leader of the human race (I assume) is hunting the mysterious "farn beast". He has roped in as guides two businessmen who have apparently previously visited the planet and bagged a farn beast. Meanwhile, an alien force is supposed to be nosing around the planet. The main viewpoint characters are the two businessmen, who make their resentment of the leader clear -- and who feel even worse when the leader decides to use one of them as bait. The bulk is the story is fairly familiar cynical comedy about bad and worse people variously bumbling around and mistreating each other ... and then the ending, quite literally, springs a little trap. Nice story, not a classic but solid work.

Kris Neville (1925-1980) had one of the interesting disappointing careers in the field. He was a native of Carthage, MO, home of Belle Starr and the great baseball pitcher Carl Hubbell and the far from great (indeed criminal) Missouri Attorney General William Webster, but NOT related to "North Carthage", the fictional town where Gillian Flynn's bestseller Gone Girl is set. (Carthage is near Joplin, entirely across the state from the Mississippi, on which North Carthage is said to sit.)) Thus Neville is the second Missourian in a row I've covered. He lived most of his adult life in California, and began publishing short fiction in 1949, and quickly made an impact, most notably with "Bettyann" (1951), but also "Hunt the Hunter" (1951) and "The Toy" (1952) among others. He also published perhaps a half-dozen novels, the last of which, Run, the Spearmaker, has only been published in Japan, except for an excerpt in the Riverside Quarterly. (It was co-written with his wife Lil, as were other late stories.) The novels were mostly expansions or fixups of earlier stories, and made little impact.

There is little question that he could have had a significant career. Why didn't he? Barry Malzberg, who collaborated with him on two stories and carried on an extensive correspondence, says that this was partly due to frustrated ambition -- the field, perhaps most of all its editors, were not ready to publish work of the ambition he desired. Another reason could be that he had a very good job, a technical writer and an expert on epoxies, which he seems to have liked and in which he was highly respected. Sometimes we readers forget that much as we want to see promising writers keep at it, there are other, equally rewarding, careers, and it's not our call what a given person chooses to do with their life. (I think of P. J. Plauger sometimes in this context.)

Astounding, March 1951

"Casting Office", by "Henderson Starke" (Kris Neville) is set just where it says -- in a casting office. The Actors seem pretty upset with the latest play, and the Critics are hammering it. The Author is peeved. It doesn't take long to figure out what's really going on, and what the "play" really is. Campbell calls it a fantasy, kind of by way of apology to Astounding's readers. There are some cute bits, but it goes on a bit long, and the central twist idea is so clear from the start that I think the story spends too much time acting like the reader can't guess.

Galaxy, June 1951

"Hunt the Hunter" is set on a distant planet where the leader of the human race (I assume) is hunting the mysterious "farn beast". He has roped in as guides two businessmen who have apparently previously visited the planet and bagged a farn beast. Meanwhile, an alien force is supposed to be nosing around the planet. The main viewpoint characters are the two businessmen, who make their resentment of the leader clear -- and who feel even worse when the leader decides to use one of them as bait. The bulk is the story is fairly familiar cynical comedy about bad and worse people variously bumbling around and mistreating each other ... and then the ending, quite literally, springs a little trap. Nice story, not a classic but solid work.

Avon Science Fiction and Fantasy Reader, April 1953

"As Holy and Enchanted" is another story Kris Neville wrote under the name "Henderson Starke". A lonely, ordinary, man name Nick likes to walk in the part on Sundays, representing a more peaceful and natural break from his usual life in the city and work in a shop (perhaps a machine shop?) One Sunday at a fountain he happens across lovely girl name Mona, who seems enchanted by him, and they spend the day together, eating at restaurants and such. Nick falls for her immediately, and she seems intrigued by him -- but the reader, of course, knows right away what sort of creature (or spirit) she is, so the ending is never in doubt. A nicely done bittersweet piece.

(This story appears, of course, on my list of stories with titles taken from "Kubla Khan".)

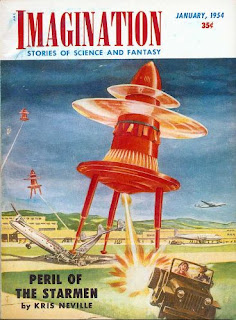

Imagination, January 1954

The cover story (illustrated rather garishly by W. E. Terry) is "Peril of the Starmen", by Kris Neville. Earth is visited by aliens, and we (the readers) learn immediately that their plan is to blow up the planet. (Apparently they subscribe to the logic that I think I saw stated in Charles Pellegrino and George Zebrowski's The Killing Star -- once a species is capable of space flight they are a potential danger, so the smart thing to do is destroy them first.) Of course, the aliens' message is one of peace. One of the aliens, however, begins to have doubts. Set against the aliens' plans is conflict in the US government. Some are eager to welcome the aliens, but another faction, led by a Senator from Missouri who might be described in contemporary terms as "Trumpian", wants nothing to do with the aliens. In essence, they are right, but for totally wrong reasons. The premise is intriguing, but the story goes on a bit too long, mostly turning on an implausible love story between the doubtful alien and the Senator's sister.

9 Tales of Space and Time, 1954

"Overture" is the direct sequel to "Bettyann". (The two stories were combined, presumably with additional material, into a novel in 1970, and another story, "Bettyann's Children", written with Lil Neville, appeared in 1973.) (Obviously, spoilers for "Bettyann" follow.) The story opens with Bettyann, having left the ship in which her alien relatives were planning to take her away, using her shapechanging ability to fly back to her true home, in Southwest Missouri. She must now come to terms with her newly revealed alien abilities, and somehow explain to her parents why she suddenly left Smith College. She becomes obsessed with the idea of making a difference -- perhaps by using her powers to heal people, and she also begins to fall for the much older local doctor. Not much else really happens -- a couple of minor health crises, her young love, her relationship with her adoptive parents -- but the story is very nicely told, sweet, well-written.

Galaxy, October 1968

Kris Neville's "Thyre Planet" is a bit more serious, if not entirely so. The story has two foci, and I'm not sure they work together. On the one hand it's a fairly broad satire of the executive personality, almost Dilbertian in spots, as Mr. Bellflower, a very well-trained expert executive, is hired by Thyre planet to solve the reliability problem with their transport booths, which were left by the natives of Thyre, who have all disappeared. So Bellflower's strategies are shown, which proved to be more based on establishing a power base and keeping the money flowing than actually solving the problem. Thus, a solution to the problem is the worst thing that could happen -- despite the fact that thousands of people a year are lost in the transport booths. The other focus is of course the problem -- and its solution, which is fairly clever, if, I think easily guessable. I liked both aspects of the story, but they seem to sit a little uneasily together.

F&SF, December 1970

"The Reality Machine", by Kris Neville, is a brief, dark, satire that follows an advisor to the President as he tries to brief him on the progress of the title machine, which we eventually learn, really is altering reality. The story seems darkly prescient in presenting an advisor who despite some apparent competence defers entirely to his worthless President; and a President who is happy to deny reality. How did Neville know?

Universe 3, 1974

Kris Neville's "Survival Problems" is, somewhat like "The Reality Machine", a dark satire on American politics. It mainly follows a successful scientist at a Mortuary institute, an expert in preserving people after their death, who wins a lottery to get life extension (at the cost of slowing one's brain processes so they become very stupid.) But first he must deal with crises at his job ... and then it becomes necessary to preserve the President himself ... the story runs on long enough to make the mordant points it wants to make, without really developing a plot -- which is OK, I suppose, because Neville doesn what he wants in its space.

Imagination, January 1954

|

| (Cover by W. E. Terry) |

9 Tales of Space and Time, 1954

|

| (Cover by W. Thut) |

Galaxy, October 1968

Kris Neville's "Thyre Planet" is a bit more serious, if not entirely so. The story has two foci, and I'm not sure they work together. On the one hand it's a fairly broad satire of the executive personality, almost Dilbertian in spots, as Mr. Bellflower, a very well-trained expert executive, is hired by Thyre planet to solve the reliability problem with their transport booths, which were left by the natives of Thyre, who have all disappeared. So Bellflower's strategies are shown, which proved to be more based on establishing a power base and keeping the money flowing than actually solving the problem. Thus, a solution to the problem is the worst thing that could happen -- despite the fact that thousands of people a year are lost in the transport booths. The other focus is of course the problem -- and its solution, which is fairly clever, if, I think easily guessable. I liked both aspects of the story, but they seem to sit a little uneasily together.

F&SF, December 1970

"The Reality Machine", by Kris Neville, is a brief, dark, satire that follows an advisor to the President as he tries to brief him on the progress of the title machine, which we eventually learn, really is altering reality. The story seems darkly prescient in presenting an advisor who despite some apparent competence defers entirely to his worthless President; and a President who is happy to deny reality. How did Neville know?

Universe 3, 1974

Kris Neville's "Survival Problems" is, somewhat like "The Reality Machine", a dark satire on American politics. It mainly follows a successful scientist at a Mortuary institute, an expert in preserving people after their death, who wins a lottery to get life extension (at the cost of slowing one's brain processes so they become very stupid.) But first he must deal with crises at his job ... and then it becomes necessary to preserve the President himself ... the story runs on long enough to make the mordant points it wants to make, without really developing a plot -- which is OK, I suppose, because Neville doesn what he wants in its space.

Friday, June 19, 2020

Birthday Review: Stories of Robert Moore Williams

|

| (Cover by Jeff Jones) |

I found his stories rather ordinary, but generally professionally done. Here are looks at a few stories of his I have read in some older SF magazines.

I have also reviewed a couple of his Ace Doubles here.

The Star Wasps

King of the Fourth Planet

Super Science Stories, May 1950

"The Soul Makers" by Robert Moore Williams is one of two stories dealing with Nuclear War. (If you ever see an SF magazine from the early 50s without a Nuclear War story, you can bet it's a fake.) In this case the Americans are fighting the East Bloc, with the help of newly invented robots. The robots are acting erratically however -- and it turns out they have realized that the fallout from the bombs has already doomed humanity, and they are planning for the future.

Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1951

Robert Moore Williams' "The Void Beyond" posits that space travel is so painful that only young men -- no women, and no one over 30 -- can survive it. Eric Gaunt is a veteran captain, 28 or so, who is disgusted when a woman tries to come aboard, having bought her ticket legally with her ambiguous name, Frances Marion. So then the woman stows away ... and when they catch her she insists that the problem is in their head and if they just exhibit will power they'll be able to tolerate space, just like she will. The ending is a mild twist. Generally a pretty silly idea and execution, with a predictable romance tacked on.

Imaginative Tales, July 1957

As for Robert Moore Williams' "The Red Rash Deaths", it's about a policeman investigating a mysterious plague -- a terribly contagious red rash has caused dozens of hundreds of deaths. He tracks down a strange man who seems associated with the deaths ... and a deus ex machina (or ex futura) solves his predicament.

Super Science Stories, May 1958

Robert Moore Williams (name given as "Robert M. Williams" on the TOC, but the full name shown on the story page) contributes "I Want to Go Home" (3500 words), about a troubled boy who has spent his whole life obsessed with the idea that he is out of place in our world, and he wants to go home. He eventually infects the police psychiatrist assigned to his case with the same concern. A minor story, but Williams does come to an unexpected conclusion.

If, October 1965

"Short Trip to Nowhere", by Robert Moore Williams, is set in the distant future of 2010, where there are antigravity beds and sleep machines. One night the protagonist is a accosted by someone in his sleep -- and after wondering who could talk to him via the sleep machine, he realizes that his 3-year-old daughter also seems to talk to -- and play with -- someone while she sleeps. This soon leads to the creature in the sleep world luring the child into his "world" -- and when the Dad talks to the creature via his sleep machine he quickly realizes that this creature has no notion that his world isn't made for humans -- for example, there's no food there. Kind of a trivial piece, really.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)