The Other Nineteenth Century, by Avram Davidson

a review by Rich Horton

A little while ago, for Avram Davidson's birthday, I posted a "review" I had done of this book for my blog, almost two decades ago. It was a carelessly tossed-off piece, arguably OK for a blog post (though still wrongheaded as I have found!), but I never should have reposted it.

I got some criticism, gentle and very fair. And I thought, "Rereading Avram Davidson is never a bad thing! Why not reread the book!" And so I have.

To begin with -- stupid things I said in that first review -- for one thing, I complained that not all the stories are really set in the 19th Century. To which the simple answer is, "So what!". In fact, most at least touch on the 19th Century, and those that don't are either from a bit earlier, or at least have a certain redolence of that time about them. (Indeed, if you choose to end the 19th Century not with the calendar's demarcation but instead the beginning of World War I, as some do, just as some end the '50s with Kennedy's assassination, a couple further stories come in, including one which explicitly is placed right at that event.) Second: I bitched about "Mickelrede", a rather strange piece that Michael Swanwick put together from notes Davidson had left for an abandoned novel. On rereading that piece, I wonder what the heck I was thinking when I read it the first time.

Anyway, to the burden of my new review. The Other Nineteenth Century was the third Davidson collection in four years to come from St. Martins or Tor, after The Avram Davidson Treasury and The Investigations of Avram Davidson, so in a sense it was picking through leftovers, especially as all three books mostly skirted his two acclaimed short story series, the Eszterhazy and Limekiller stories. (This book does include a later and rather short Eszterhazy piece, and one story that appeared in the Treasury.) But the richness of Davidson's catalogue is thus revealed -- even with that constraint, and with the thematic constraint of choosing pieces that at least vaguely suggest the 19th Century, the book is worthwhile throughout, and includes a few pieces that stand among his very best stories.

For example, "Dragon Skin Drum", which I prefer to his slightly better known story of post-War China, "Dagon". "Dragon Skin Drum" is told from the viewpoint of an earnest and naive soldier, who visits a restaurant in the Forbidden City in the company of his more rough-edged friend, Gunnery Sergeant Jackson. Howard tries out his knowledge of Chinese, and tries to understand the local guides/interpreters he must hire, and puts up with Jackson's crudeness, and hears the story of the title drum ... and we learn a bit about these two characters (Jackson not surprisingly the savvier), and about this particular time, right as Mao is marching.

Also, "The Montavarde Camera", a really effective biter bit piece about a man who buys a camera from one of those mysterious little shops you can never find again. The camera has a sinister background -- people whose pictures are taken tend to die soon. And the man has a nagging wife ... We see where this is going, and it gets there just right.

Certainly among the best of Davidson's late stories is "El Vilvoy de las Islas". Many have noticed that his style grew more mannered, more prolix, late in his life. Sometimes this habit was taken to excess, but sometimes it worked, as here. The narrator seems to be the author himself, on a trip through South America. Feeling too tired to continue, he stops in a country called Ereguay, and eventually hears the story of "El Vilvoy" -- a young man from the Islas Encantadas, who, visiting the mainland, saves a woman from an attack, and becomes a sensation for a while. It eventuates that he and his family, on a nearly deserted small isle, live a simple life ... but there are mysteries. And so Davidson wanders through various newspaper accounts, oral stories, and so on, letting us piece together the story of the "Wild Boy".

"What Strange Stars and Skies" has been a favorite of mine for a long time -- telling of a Dame Philippa, who does charity work in the slums of London, and when ministering to the poor near a sailor's house, encounters a very curious press gang. The last line is wonderful.

I first encountered "The Man Who Saw the Elephant" in this book, and it delighted and moved me -- it's about a Quaker couple, the wife hardworking and only just tolerant of her husband's dreams ... one of which is to see the elephant that a traveling showman advertises. In the end, the husband does get to see ... well, if not an elephant something quite wonderful anyway, it seems to me.

I don't perhaps have time to discuss every story. Many turn on portraying a reasonably well known historical incident, or set of characters, from a slant -- and letting the reader figure out what's really going on. Davidson also delights in Alternate History, such as "O Brave Old World!", about the radically different history of America had Frederick of Hanover survived and moved to the Colonies; or "Pebble in Time" (with Cynthia Goldstone) in which a Mormon travels back in time to witness Brigham Young reaching the Salt Lake and unexpectedly changes history, leading to a different 1960s in San Francisco (though concluding with a labored pun that doesn't land as easily now as it might have when first published.) The stories are a mix of historical fiction, mystery, and SF/F, from a very wide range of sources. The editors and a couple more people contribute short afterwords, rather a mixed bag -- some add intriguing detail (including, in one case, Davidson's editorial interaction with Robert P. Mills), others, alas, rather clumsily step on the subtle point Davidson is reaching for.

Finally I need to address a quite odd posthumous collaboration that closes the book, "Mickelrede", put together by Michael Swanwick from a set of notes that Davidson left for an unfinished novel begun in the early '60s. In my previous review, I was very dismissive of the story, which I really failed to understand. Honestly, I'm ashamed, because actually it's not that difficult to follow. It helps somewhat to get the context right -- now I can see that the notes really do look like they might plausibly have become a novel very much in the mode Davidson was using for his earliest short novels, such as Masters of the Maze. The novel involves a contemporary academic thrust into another world (possibly the future) to serve in some sort of combat games, and also to deal with the Green King and the holy Mickelrede, a sacred object that seems to be a slide rule. There is a woman involved, of course, and Swanwick advances some alternate plot points, such as changing the slide rule to a Difference Engine, and the woman to Ada Lovelace. Davidson's novels, at this point in his career, were not his best work, and I can imagine well enough the novel which might have resulted, which would have been enjoyable but not great (sort of a better written Ken Bulmer, for those who remember Bulmer) -- the possibility of a later true collaboration between Swanwick and Davidson, incorporating Swanwick's ideas, is intriguing but likely would not have been the best use of either authors talents -- though who knows? The prose in this fragment seems more Swanwick than Davidson, but that's hardly a complaint, and there certainly are hints of Davidson as well.

Saturday, July 4, 2020

Monday, June 22, 2020

Very Belated Birthday Review: Stories of Kris Neville

Here's a very belated birthday review for Kris Neville, born May 9, 1925. I wanted to write about him, but I had only reviewed three or four of his stories, so I dug up a few more and read them ...

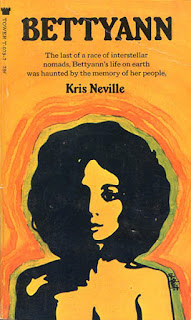

Kris Neville (1925-1980) had one of the interesting disappointing careers in the field. He was a native of Carthage, MO, home of Belle Starr and the great baseball pitcher Carl Hubbell and the far from great (indeed criminal) Missouri Attorney General William Webster, but NOT related to "North Carthage", the fictional town where Gillian Flynn's bestseller Gone Girl is set. (Carthage is near Joplin, entirely across the state from the Mississippi, on which North Carthage is said to sit.)) Thus Neville is the second Missourian in a row I've covered. He lived most of his adult life in California, and began publishing short fiction in 1949, and quickly made an impact, most notably with "Bettyann" (1951), but also "Hunt the Hunter" (1951) and "The Toy" (1952) among others. He also published perhaps a half-dozen novels, the last of which, Run, the Spearmaker, has only been published in Japan, except for an excerpt in the Riverside Quarterly. (It was co-written with his wife Lil, as were other late stories.) The novels were mostly expansions or fixups of earlier stories, and made little impact.

There is little question that he could have had a significant career. Why didn't he? Barry Malzberg, who collaborated with him on two stories and carried on an extensive correspondence, says that this was partly due to frustrated ambition -- the field, perhaps most of all its editors, were not ready to publish work of the ambition he desired. Another reason could be that he had a very good job, a technical writer and an expert on epoxies, which he seems to have liked and in which he was highly respected. Sometimes we readers forget that much as we want to see promising writers keep at it, there are other, equally rewarding, careers, and it's not our call what a given person chooses to do with their life. (I think of P. J. Plauger sometimes in this context.)

Astounding, March 1951

"Casting Office", by "Henderson Starke" (Kris Neville) is set just where it says -- in a casting office. The Actors seem pretty upset with the latest play, and the Critics are hammering it. The Author is peeved. It doesn't take long to figure out what's really going on, and what the "play" really is. Campbell calls it a fantasy, kind of by way of apology to Astounding's readers. There are some cute bits, but it goes on a bit long, and the central twist idea is so clear from the start that I think the story spends too much time acting like the reader can't guess.

Galaxy, June 1951

"Hunt the Hunter" is set on a distant planet where the leader of the human race (I assume) is hunting the mysterious "farn beast". He has roped in as guides two businessmen who have apparently previously visited the planet and bagged a farn beast. Meanwhile, an alien force is supposed to be nosing around the planet. The main viewpoint characters are the two businessmen, who make their resentment of the leader clear -- and who feel even worse when the leader decides to use one of them as bait. The bulk is the story is fairly familiar cynical comedy about bad and worse people variously bumbling around and mistreating each other ... and then the ending, quite literally, springs a little trap. Nice story, not a classic but solid work.

Kris Neville (1925-1980) had one of the interesting disappointing careers in the field. He was a native of Carthage, MO, home of Belle Starr and the great baseball pitcher Carl Hubbell and the far from great (indeed criminal) Missouri Attorney General William Webster, but NOT related to "North Carthage", the fictional town where Gillian Flynn's bestseller Gone Girl is set. (Carthage is near Joplin, entirely across the state from the Mississippi, on which North Carthage is said to sit.)) Thus Neville is the second Missourian in a row I've covered. He lived most of his adult life in California, and began publishing short fiction in 1949, and quickly made an impact, most notably with "Bettyann" (1951), but also "Hunt the Hunter" (1951) and "The Toy" (1952) among others. He also published perhaps a half-dozen novels, the last of which, Run, the Spearmaker, has only been published in Japan, except for an excerpt in the Riverside Quarterly. (It was co-written with his wife Lil, as were other late stories.) The novels were mostly expansions or fixups of earlier stories, and made little impact.

There is little question that he could have had a significant career. Why didn't he? Barry Malzberg, who collaborated with him on two stories and carried on an extensive correspondence, says that this was partly due to frustrated ambition -- the field, perhaps most of all its editors, were not ready to publish work of the ambition he desired. Another reason could be that he had a very good job, a technical writer and an expert on epoxies, which he seems to have liked and in which he was highly respected. Sometimes we readers forget that much as we want to see promising writers keep at it, there are other, equally rewarding, careers, and it's not our call what a given person chooses to do with their life. (I think of P. J. Plauger sometimes in this context.)

Astounding, March 1951

"Casting Office", by "Henderson Starke" (Kris Neville) is set just where it says -- in a casting office. The Actors seem pretty upset with the latest play, and the Critics are hammering it. The Author is peeved. It doesn't take long to figure out what's really going on, and what the "play" really is. Campbell calls it a fantasy, kind of by way of apology to Astounding's readers. There are some cute bits, but it goes on a bit long, and the central twist idea is so clear from the start that I think the story spends too much time acting like the reader can't guess.

Galaxy, June 1951

"Hunt the Hunter" is set on a distant planet where the leader of the human race (I assume) is hunting the mysterious "farn beast". He has roped in as guides two businessmen who have apparently previously visited the planet and bagged a farn beast. Meanwhile, an alien force is supposed to be nosing around the planet. The main viewpoint characters are the two businessmen, who make their resentment of the leader clear -- and who feel even worse when the leader decides to use one of them as bait. The bulk is the story is fairly familiar cynical comedy about bad and worse people variously bumbling around and mistreating each other ... and then the ending, quite literally, springs a little trap. Nice story, not a classic but solid work.

Avon Science Fiction and Fantasy Reader, April 1953

"As Holy and Enchanted" is another story Kris Neville wrote under the name "Henderson Starke". A lonely, ordinary, man name Nick likes to walk in the part on Sundays, representing a more peaceful and natural break from his usual life in the city and work in a shop (perhaps a machine shop?) One Sunday at a fountain he happens across lovely girl name Mona, who seems enchanted by him, and they spend the day together, eating at restaurants and such. Nick falls for her immediately, and she seems intrigued by him -- but the reader, of course, knows right away what sort of creature (or spirit) she is, so the ending is never in doubt. A nicely done bittersweet piece.

(This story appears, of course, on my list of stories with titles taken from "Kubla Khan".)

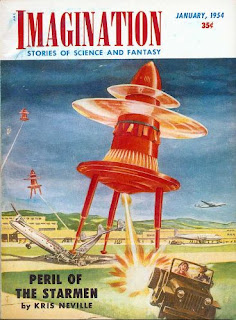

Imagination, January 1954

The cover story (illustrated rather garishly by W. E. Terry) is "Peril of the Starmen", by Kris Neville. Earth is visited by aliens, and we (the readers) learn immediately that their plan is to blow up the planet. (Apparently they subscribe to the logic that I think I saw stated in Charles Pellegrino and George Zebrowski's The Killing Star -- once a species is capable of space flight they are a potential danger, so the smart thing to do is destroy them first.) Of course, the aliens' message is one of peace. One of the aliens, however, begins to have doubts. Set against the aliens' plans is conflict in the US government. Some are eager to welcome the aliens, but another faction, led by a Senator from Missouri who might be described in contemporary terms as "Trumpian", wants nothing to do with the aliens. In essence, they are right, but for totally wrong reasons. The premise is intriguing, but the story goes on a bit too long, mostly turning on an implausible love story between the doubtful alien and the Senator's sister.

9 Tales of Space and Time, 1954

"Overture" is the direct sequel to "Bettyann". (The two stories were combined, presumably with additional material, into a novel in 1970, and another story, "Bettyann's Children", written with Lil Neville, appeared in 1973.) (Obviously, spoilers for "Bettyann" follow.) The story opens with Bettyann, having left the ship in which her alien relatives were planning to take her away, using her shapechanging ability to fly back to her true home, in Southwest Missouri. She must now come to terms with her newly revealed alien abilities, and somehow explain to her parents why she suddenly left Smith College. She becomes obsessed with the idea of making a difference -- perhaps by using her powers to heal people, and she also begins to fall for the much older local doctor. Not much else really happens -- a couple of minor health crises, her young love, her relationship with her adoptive parents -- but the story is very nicely told, sweet, well-written.

Galaxy, October 1968

Kris Neville's "Thyre Planet" is a bit more serious, if not entirely so. The story has two foci, and I'm not sure they work together. On the one hand it's a fairly broad satire of the executive personality, almost Dilbertian in spots, as Mr. Bellflower, a very well-trained expert executive, is hired by Thyre planet to solve the reliability problem with their transport booths, which were left by the natives of Thyre, who have all disappeared. So Bellflower's strategies are shown, which proved to be more based on establishing a power base and keeping the money flowing than actually solving the problem. Thus, a solution to the problem is the worst thing that could happen -- despite the fact that thousands of people a year are lost in the transport booths. The other focus is of course the problem -- and its solution, which is fairly clever, if, I think easily guessable. I liked both aspects of the story, but they seem to sit a little uneasily together.

F&SF, December 1970

"The Reality Machine", by Kris Neville, is a brief, dark, satire that follows an advisor to the President as he tries to brief him on the progress of the title machine, which we eventually learn, really is altering reality. The story seems darkly prescient in presenting an advisor who despite some apparent competence defers entirely to his worthless President; and a President who is happy to deny reality. How did Neville know?

Universe 3, 1974

Kris Neville's "Survival Problems" is, somewhat like "The Reality Machine", a dark satire on American politics. It mainly follows a successful scientist at a Mortuary institute, an expert in preserving people after their death, who wins a lottery to get life extension (at the cost of slowing one's brain processes so they become very stupid.) But first he must deal with crises at his job ... and then it becomes necessary to preserve the President himself ... the story runs on long enough to make the mordant points it wants to make, without really developing a plot -- which is OK, I suppose, because Neville doesn what he wants in its space.

Imagination, January 1954

|

| (Cover by W. E. Terry) |

9 Tales of Space and Time, 1954

|

| (Cover by W. Thut) |

Galaxy, October 1968

Kris Neville's "Thyre Planet" is a bit more serious, if not entirely so. The story has two foci, and I'm not sure they work together. On the one hand it's a fairly broad satire of the executive personality, almost Dilbertian in spots, as Mr. Bellflower, a very well-trained expert executive, is hired by Thyre planet to solve the reliability problem with their transport booths, which were left by the natives of Thyre, who have all disappeared. So Bellflower's strategies are shown, which proved to be more based on establishing a power base and keeping the money flowing than actually solving the problem. Thus, a solution to the problem is the worst thing that could happen -- despite the fact that thousands of people a year are lost in the transport booths. The other focus is of course the problem -- and its solution, which is fairly clever, if, I think easily guessable. I liked both aspects of the story, but they seem to sit a little uneasily together.

F&SF, December 1970

"The Reality Machine", by Kris Neville, is a brief, dark, satire that follows an advisor to the President as he tries to brief him on the progress of the title machine, which we eventually learn, really is altering reality. The story seems darkly prescient in presenting an advisor who despite some apparent competence defers entirely to his worthless President; and a President who is happy to deny reality. How did Neville know?

Universe 3, 1974

Kris Neville's "Survival Problems" is, somewhat like "The Reality Machine", a dark satire on American politics. It mainly follows a successful scientist at a Mortuary institute, an expert in preserving people after their death, who wins a lottery to get life extension (at the cost of slowing one's brain processes so they become very stupid.) But first he must deal with crises at his job ... and then it becomes necessary to preserve the President himself ... the story runs on long enough to make the mordant points it wants to make, without really developing a plot -- which is OK, I suppose, because Neville doesn what he wants in its space.

Friday, June 19, 2020

Birthday Review: Stories of Robert Moore Williams

|

| (Cover by Jeff Jones) |

I found his stories rather ordinary, but generally professionally done. Here are looks at a few stories of his I have read in some older SF magazines.

I have also reviewed a couple of his Ace Doubles here.

The Star Wasps

King of the Fourth Planet

Super Science Stories, May 1950

"The Soul Makers" by Robert Moore Williams is one of two stories dealing with Nuclear War. (If you ever see an SF magazine from the early 50s without a Nuclear War story, you can bet it's a fake.) In this case the Americans are fighting the East Bloc, with the help of newly invented robots. The robots are acting erratically however -- and it turns out they have realized that the fallout from the bombs has already doomed humanity, and they are planning for the future.

Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1951

Robert Moore Williams' "The Void Beyond" posits that space travel is so painful that only young men -- no women, and no one over 30 -- can survive it. Eric Gaunt is a veteran captain, 28 or so, who is disgusted when a woman tries to come aboard, having bought her ticket legally with her ambiguous name, Frances Marion. So then the woman stows away ... and when they catch her she insists that the problem is in their head and if they just exhibit will power they'll be able to tolerate space, just like she will. The ending is a mild twist. Generally a pretty silly idea and execution, with a predictable romance tacked on.

Imaginative Tales, July 1957

As for Robert Moore Williams' "The Red Rash Deaths", it's about a policeman investigating a mysterious plague -- a terribly contagious red rash has caused dozens of hundreds of deaths. He tracks down a strange man who seems associated with the deaths ... and a deus ex machina (or ex futura) solves his predicament.

Super Science Stories, May 1958

Robert Moore Williams (name given as "Robert M. Williams" on the TOC, but the full name shown on the story page) contributes "I Want to Go Home" (3500 words), about a troubled boy who has spent his whole life obsessed with the idea that he is out of place in our world, and he wants to go home. He eventually infects the police psychiatrist assigned to his case with the same concern. A minor story, but Williams does come to an unexpected conclusion.

If, October 1965

"Short Trip to Nowhere", by Robert Moore Williams, is set in the distant future of 2010, where there are antigravity beds and sleep machines. One night the protagonist is a accosted by someone in his sleep -- and after wondering who could talk to him via the sleep machine, he realizes that his 3-year-old daughter also seems to talk to -- and play with -- someone while she sleeps. This soon leads to the creature in the sleep world luring the child into his "world" -- and when the Dad talks to the creature via his sleep machine he quickly realizes that this creature has no notion that his world isn't made for humans -- for example, there's no food there. Kind of a trivial piece, really.

Tuesday, June 9, 2020

Birthday Review: The Coming, by Joe Haldeman

Joe Haldeman turns 77 today. He's an SFWA Grand Master, one of the truly fine writers of his generation. He's one of those writers who made a huge splash early in his career, with his second novel, first SF novel, The Forever War; and in some ways I sometimes think that's made people forget how consistently strong his novels have been throughout his career. I haven't seen a novel since Work Done For Hire in 2014 -- I hope we might have more coming. Here is a review based on a blog post I did of one of his solid late middle-period books.

The Coming, by Joe Haldeman

a review by Rich Horton

Joe Haldeman's newest book is The Coming. This is a shortish, nicely executed, book about the receipt of a signal from an alien ship. Haldeman explicitly credits James Gunn's fine novel about receiving messages from aliens, The Listeners, as an influence, but The Coming reminded me much more of a brilliant and underrated novel by John Kessel, Good News From Outer Space. Both books (The Coming and Kessel's novel) use the idea of aliens coming to Earth as a fulcrum for an exploration of U. S. society.

Joe Haldeman's newest book is The Coming. This is a shortish, nicely executed, book about the receipt of a signal from an alien ship. Haldeman explicitly credits James Gunn's fine novel about receiving messages from aliens, The Listeners, as an influence, but The Coming reminded me much more of a brilliant and underrated novel by John Kessel, Good News From Outer Space. Both books (The Coming and Kessel's novel) use the idea of aliens coming to Earth as a fulcrum for an exploration of U. S. society.

The Coming opens with an astronomer at the University of Florida, Aurora Bell, recognizing an anomalous signal from a gamma ray telescope. It turns out to be a short message saying, in English, "We're Coming". And she is able to confirm that it comes from a source about a tenth of a light year from Earth, blue-shifted so that it must be traveling at 99 percent of the speed of light.

The novel is neatly structured so that the point of view smoothly shifts from scene to scene, such that each new scene begins from the POV of a character encountered just previously. This gives the whole book a certain fluidity and a certain sense of movement, and it also alows the author to gracefully explore events through the eyes of a wide variety of characters. What we see is a portrait of\ the city of Gainesville, Florida, in the 2054. The characters include Dr. Bell and her husband, a composer and also a professor; several colleagues of Dr. Bell, significantly including her assistant, a mysterious immigrant from Cuba named Pepe Parker; a restaurant owner in the University neighbourhood; a Mafia bag man; a policeman; a couple of reporters; a homeless lady; a university student making extra money by "acting" in "virtual reality" pornographic episodes; and more. Haldeman uses this tapestry of viewpoints to portray the reaction of the wider populace to the Coming of the aliens, but more importantly, he uses it to portray the social and political and technological landscape of this particular future.

Haldeman's portrayal is interesting. The future tech includes highly computerized homes and holographic conference calls and the above-mentioned virtual porn. Environmentally, the world is facing advanced global warming, with much flooding, unusual winters and summers, sunblock essential at all times lest you get skin cancer, etc. The political view of the US is a bit disappointing: his view is a cynical redaction of contemporary politics, with all but unchanged Democratic and Republican parties, and an image-besotten Republican idiot as President. I'd have rather seen a more altered political landscape. There are snippets of world politics that present some interesting changes: an important subplot concerns a looming war between France and Germany. The major social change in the U. S. that affects the book is that much stricter laws about sexual activity have been implemented: homosexuality is completely criminalized, while even some consensual married activities are apparently against the law (though not often enforced). I confess I find these last changes implausible and counter to real social trends in the U. S. today: perhaps I am simply an optimist. His overall future is somewhat depressing but not without hope, and it is quite interesting. The characters are well-portrayed and involving.

The plot is also interesting. It turns on political manoeuvring about the proper response to the arrival of the aliens, as well as the calamitous revealing of a dark secret in the Bells' past. There is a certain amount of action and intrigue, resolved nicely enough. And Haldeman's climax, involving the promised arrival of the aliens, is well-handled, and the reader isn't cheated. Overall the book feels just a bit slight, but it's a fine effort, and a good solid read.

The Coming, by Joe Haldeman

a review by Rich Horton

Joe Haldeman's newest book is The Coming. This is a shortish, nicely executed, book about the receipt of a signal from an alien ship. Haldeman explicitly credits James Gunn's fine novel about receiving messages from aliens, The Listeners, as an influence, but The Coming reminded me much more of a brilliant and underrated novel by John Kessel, Good News From Outer Space. Both books (The Coming and Kessel's novel) use the idea of aliens coming to Earth as a fulcrum for an exploration of U. S. society.

Joe Haldeman's newest book is The Coming. This is a shortish, nicely executed, book about the receipt of a signal from an alien ship. Haldeman explicitly credits James Gunn's fine novel about receiving messages from aliens, The Listeners, as an influence, but The Coming reminded me much more of a brilliant and underrated novel by John Kessel, Good News From Outer Space. Both books (The Coming and Kessel's novel) use the idea of aliens coming to Earth as a fulcrum for an exploration of U. S. society.The Coming opens with an astronomer at the University of Florida, Aurora Bell, recognizing an anomalous signal from a gamma ray telescope. It turns out to be a short message saying, in English, "We're Coming". And she is able to confirm that it comes from a source about a tenth of a light year from Earth, blue-shifted so that it must be traveling at 99 percent of the speed of light.

The novel is neatly structured so that the point of view smoothly shifts from scene to scene, such that each new scene begins from the POV of a character encountered just previously. This gives the whole book a certain fluidity and a certain sense of movement, and it also alows the author to gracefully explore events through the eyes of a wide variety of characters. What we see is a portrait of\ the city of Gainesville, Florida, in the 2054. The characters include Dr. Bell and her husband, a composer and also a professor; several colleagues of Dr. Bell, significantly including her assistant, a mysterious immigrant from Cuba named Pepe Parker; a restaurant owner in the University neighbourhood; a Mafia bag man; a policeman; a couple of reporters; a homeless lady; a university student making extra money by "acting" in "virtual reality" pornographic episodes; and more. Haldeman uses this tapestry of viewpoints to portray the reaction of the wider populace to the Coming of the aliens, but more importantly, he uses it to portray the social and political and technological landscape of this particular future.

Haldeman's portrayal is interesting. The future tech includes highly computerized homes and holographic conference calls and the above-mentioned virtual porn. Environmentally, the world is facing advanced global warming, with much flooding, unusual winters and summers, sunblock essential at all times lest you get skin cancer, etc. The political view of the US is a bit disappointing: his view is a cynical redaction of contemporary politics, with all but unchanged Democratic and Republican parties, and an image-besotten Republican idiot as President. I'd have rather seen a more altered political landscape. There are snippets of world politics that present some interesting changes: an important subplot concerns a looming war between France and Germany. The major social change in the U. S. that affects the book is that much stricter laws about sexual activity have been implemented: homosexuality is completely criminalized, while even some consensual married activities are apparently against the law (though not often enforced). I confess I find these last changes implausible and counter to real social trends in the U. S. today: perhaps I am simply an optimist. His overall future is somewhat depressing but not without hope, and it is quite interesting. The characters are well-portrayed and involving.

The plot is also interesting. It turns on political manoeuvring about the proper response to the arrival of the aliens, as well as the calamitous revealing of a dark secret in the Bells' past. There is a certain amount of action and intrigue, resolved nicely enough. And Haldeman's climax, involving the promised arrival of the aliens, is well-handled, and the reader isn't cheated. Overall the book feels just a bit slight, but it's a fine effort, and a good solid read.

Sunday, June 7, 2020

A List of 100 (+) Books I Haven't Read

One Hundred Books on my TBR Pile

I put this list together after having previously rather carelessly posted a shabbily curated list of 100 (actually 99) books that, it was claimed, was put together by the BBC and that of which, supposedly (no proof offered) the average person had only read 6. The list also included a couple of strange duplicates, too many books by certain writers, and a couple of (in my opinion) egregiously bad books. On the other hand, most of the books on the list were actually pretty good, so it was fun discussing it.

But then, I thought -- this might be more interesting. This list is one I made essentially from looking at my (literal and also figurative) To Be Read pile -- books I've known about for years, own in most cases, and think are awfully interesting. Some are fairly recent books (many SF) that I've been meaning to get to, others are older books, mostly in the category of "classics". Some people have noted that some of them seem like the lesser-known, and arguably "lesser", books of great writers. There are two reasons for this: some are books by writers whom I've already tried, but want to read further. So, I've read Henry Esmond and Vanity Fair, and I want to read more Thackeray, hence Pendennis. I've read Middlemarch, and want to read more Eliot, hence Daniel Deronda. I've read lots and lots of Byatt, but never got to Babel Tower, hence it's there. The other reason is that I don't necessarily agree that all these books are "lesser" ... speaking as one who hasn't read them. Is Anna Karenina "lesser" than War and Peace? I don't know, but it seems pretty major to me. Is The Blind Assassin lesser than The Handmaid's Tale? I don't think so (can't say I know) ... it's just the book that hasn't become a famous miniseries.

Anyway -- what's not on this list. First -- nothing I have already read. So don't ask me why there's no Jane Austen -- I've read her complete works. Same with Kingsley Amis. Anthony Powell. Robertson Davies. Penelope Fitzgerald. Flann O'Brien. Kipling. Flannery O'Connor. W. M. Spackman. Karen Joy Fowler. etc. etc. etc.

It is my list, and I read only English (a failure of mine, not any sort of virtue), so it's very English-language-centric, and beyond that rather Western-centric, with some attempts to broaden that. Parts of it are pretty idiosyncratically me -- but what would be the fun if that wasn't true? And this is a shame-free zone, I hope -- if you haven't read these, great! Neither have I! That just means we have more to look forward to!

I have also expanded my additional list to include some excellent suggestions offered after my original Facebook post. Those appear at the end.

I put this list together after having previously rather carelessly posted a shabbily curated list of 100 (actually 99) books that, it was claimed, was put together by the BBC and that of which, supposedly (no proof offered) the average person had only read 6. The list also included a couple of strange duplicates, too many books by certain writers, and a couple of (in my opinion) egregiously bad books. On the other hand, most of the books on the list were actually pretty good, so it was fun discussing it.

But then, I thought -- this might be more interesting. This list is one I made essentially from looking at my (literal and also figurative) To Be Read pile -- books I've known about for years, own in most cases, and think are awfully interesting. Some are fairly recent books (many SF) that I've been meaning to get to, others are older books, mostly in the category of "classics". Some people have noted that some of them seem like the lesser-known, and arguably "lesser", books of great writers. There are two reasons for this: some are books by writers whom I've already tried, but want to read further. So, I've read Henry Esmond and Vanity Fair, and I want to read more Thackeray, hence Pendennis. I've read Middlemarch, and want to read more Eliot, hence Daniel Deronda. I've read lots and lots of Byatt, but never got to Babel Tower, hence it's there. The other reason is that I don't necessarily agree that all these books are "lesser" ... speaking as one who hasn't read them. Is Anna Karenina "lesser" than War and Peace? I don't know, but it seems pretty major to me. Is The Blind Assassin lesser than The Handmaid's Tale? I don't think so (can't say I know) ... it's just the book that hasn't become a famous miniseries.

Anyway -- what's not on this list. First -- nothing I have already read. So don't ask me why there's no Jane Austen -- I've read her complete works. Same with Kingsley Amis. Anthony Powell. Robertson Davies. Penelope Fitzgerald. Flann O'Brien. Kipling. Flannery O'Connor. W. M. Spackman. Karen Joy Fowler. etc. etc. etc.

It is my list, and I read only English (a failure of mine, not any sort of virtue), so it's very English-language-centric, and beyond that rather Western-centric, with some attempts to broaden that. Parts of it are pretty idiosyncratically me -- but what would be the fun if that wasn't true? And this is a shame-free zone, I hope -- if you haven't read these, great! Neither have I! That just means we have more to look forward to!

I have also expanded my additional list to include some excellent suggestions offered after my original Facebook post. Those appear at the end.

Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart

Richard Adams, Watership Down

Isabel Allende, The House of the Spirits

Charlie Jane Anders, The City in the Middle of the Night

Eleanor Arnason, Daughter of the Bear King

Kate Atkinson, Life After Life

Margeret Atwood, The Blind Assassin

Honore de Balzac, Pere Goriot

John Barth, Giles Goat-Boy

Saul Bellow, The Adventures of Augie March

Lauren Beukes, Zoo City

Elizabeth Bowen, The Death of the Heart

Anne Bronte, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

A. S. Byatt, Babel Tower

Willa Cather, My Antonia

Eleanor Catton, The Luminaries

Anton Chekhov, Selected Stories

Wu Cheng’En, Journey to the West

C. J. Cherryh, Cyteen

Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone

Ivy Compton-Burnett, Manservant and Maidservant

Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim

John Crowley, Lord Byron’s Novel: The Evening Land

Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves

Samuel R. Delany, Tales of Neveryon

Thomas M. Disch, On Wings of Song

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

Fyodor Dostoyevksy, The Brothers Karamazov

Roddy Doyle, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha

Jennifer Egan, Manhattan Beach

George Eliot, Daniel Deronda

William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary

E. M. Forster, A Room With a View

George Macdonald Fraser, Mr. American

Elizabeth Gaskell, Cranford

Nikolai Gogol, Dead Souls

Alasdair Gray, Lanark

Henry Green, Doting

Elizabeth Hand, Curious Toys

Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd

Tsao Hsueh-Chin, Dream of the Red Chamber

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the Day

Howard Jacobson, The Finkler Question

Henry James, The Ambassadors

Marlon James, Black Leopard, Red Wolf

N. K. Jemisin, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms

James Joyce, Ulysses

Franz Kafka, The Trial

Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Margaret Laurence, Rachel, Rachel

Ursula K. Le Guin, Always Coming Home

Stanislaw Lem, Solaris

Eleanor Lerman, Radiomen

Doris Lessing, Canopus in Argus

Jonathan Lethem, Motherless Brooklyn

Karen Lord, The Best of All Possible Worlds

George MacDonald, Lilith

Naguib Mahfouz, Arabian Nights and Days

Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Love in the Time of Cholera

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Toni Morrison, Sula

Ottessa Moshfegh, Homesick for Another World

Haruki Murakami, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

Lady Murasaki, The Tale of Genji

Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities

Vladimir Nabokov, Laughter in the Dark

Helen Oyeyemi, Mr. Fox

Edgar Pangborn, Wilderness of Spring

Georges Perec, Life: A User’s Manual

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time

Alexander Pushkin, The Captain’s Daughter

Mary Renault, The King Must Die

Sally Rooney, Normal People

Matt Ruff, The Mirage

Karen Russell, Swamplandia

Walter Scott, The Heart of Midlothian

Vikram Seth, A Suitable Boy

William Shakespeare, The Two Noble Kinsmen

Zadie Smith, On Beauty

Francis Spofford, Golden Hill

Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy

Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Hard to Be a God

Elizabeth Taylor, Angel

William Makepeace Thackeray, Pendennis

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

Anthony Trollope, The Way We Live Now

John Updike, The Centaur

Jack Vance, Lyonesse: Suldrun’s Garden

Jo Walton, Lent

Janwilliam van der Wetering, The Corpse on the Dike

Edith Wharton, Summer

Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

John Williams, Stoner

Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

Xenophon, Anabasis

Margaret Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

Yevgeny Zamyatin, We

Stefan Zweig, The Royal Game

New Additions:

Ray Bradbury, Something Wicked This Way Comes

Lawrence Durrell, Constance; or, Solitary Practices

Jaraslav Hasek, The Good Solider Svejk

Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

Leena Krohn, Collected Fiction

Chen Quifan, Waste Tide

Bruno Schulz, The Street of Crocodiles

Voltaire, Candide

Edward Whittemore, Quin's Shanghai Circus

Richard Adams, Watership Down

Isabel Allende, The House of the Spirits

Charlie Jane Anders, The City in the Middle of the Night

Kate Atkinson, Life After Life

Margeret Atwood, The Blind Assassin

Honore de Balzac, Pere Goriot

John Barth, Giles Goat-Boy

Saul Bellow, The Adventures of Augie March

Lauren Beukes, Zoo City

Elizabeth Bowen, The Death of the Heart

Anne Bronte, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

A. S. Byatt, Babel Tower

Eleanor Catton, The Luminaries

Anton Chekhov, Selected Stories

Wu Cheng’En, Journey to the West

C. J. Cherryh, Cyteen

Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone

Ivy Compton-Burnett, Manservant and Maidservant

Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim

John Crowley, Lord Byron’s Novel: The Evening Land

Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves

Samuel R. Delany, Tales of Neveryon

Thomas M. Disch, On Wings of Song

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

Fyodor Dostoyevksy, The Brothers Karamazov

Roddy Doyle, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha

Jennifer Egan, Manhattan Beach

George Eliot, Daniel Deronda

William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary

E. M. Forster, A Room With a View

George Macdonald Fraser, Mr. American

Nikolai Gogol, Dead Souls

Alasdair Gray, Lanark

Henry Green, Doting

Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd

Tsao Hsueh-Chin, Dream of the Red Chamber

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the Day

Howard Jacobson, The Finkler Question

Henry James, The Ambassadors

Marlon James, Black Leopard, Red Wolf

N. K. Jemisin, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms

Franz Kafka, The Trial

Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Margaret Laurence, Rachel, Rachel

Stanislaw Lem, Solaris

Eleanor Lerman, Radiomen

Doris Lessing, Canopus in Argus

Karen Lord, The Best of All Possible Worlds

George MacDonald, Lilith

Naguib Mahfouz, Arabian Nights and Days

Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Love in the Time of Cholera

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Toni Morrison, Sula

Ottessa Moshfegh, Homesick for Another World

Haruki Murakami, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

Lady Murasaki, The Tale of Genji

Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities

Vladimir Nabokov, Laughter in the Dark

Helen Oyeyemi, Mr. Fox

Edgar Pangborn, Wilderness of Spring

Georges Perec, Life: A User’s Manual

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time

Alexander Pushkin, The Captain’s Daughter

Mary Renault, The King Must Die

Sally Rooney, Normal People

Matt Ruff, The Mirage

Karen Russell, Swamplandia

Walter Scott, The Heart of Midlothian

Vikram Seth, A Suitable Boy

William Shakespeare, The Two Noble Kinsmen

Zadie Smith, On Beauty

Francis Spofford, Golden Hill

Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy

Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Hard to Be a God

Elizabeth Taylor, Angel

William Makepeace Thackeray, Pendennis

Anthony Trollope, The Way We Live Now

John Updike, The Centaur

Jack Vance, Lyonesse: Suldrun’s Garden

Janwilliam van der Wetering, The Corpse on the Dike

Edith Wharton, Summer

Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

John Williams, Stoner

Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

Xenophon, Anabasis

Margaret Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

Yevgeny Zamyatin, We

Stefan Zweig, The Royal Game

New Additions:

Ray Bradbury, Something Wicked This Way Comes

Lawrence Durrell, Constance; or, Solitary Practices

Jaraslav Hasek, The Good Solider Svejk

Leena Krohn, Collected Fiction

Chen Quifan, Waste Tide

Bruno Schulz, The Street of Crocodiles

Voltaire, Candide

Edward Whittemore, Quin's Shanghai Circus

Sunday, May 31, 2020

Birthday Review: Stories of Bryce Walton

Bryce Walton would have turned 102 today. Bryce Walton, you say? Who he? He was a prolific contributor of short fiction in various genres between 1945 and 1969, with just one SF novel (Son of the Ocean Deeps (1952).) He was originally from Missouri, and he died in 1988. Frankly I found his work fairly mediocre -- but at times surprisingly ambitious. He's one of those names you'd have known if you read in the field in the 1950s ... but you might not remember him.

In his honor, here's a look at several of his stories that I have read in various 1950s SF publications.

Space Science Fiction, May 1952

As for the other story, "To Each His Star", it's wholly forgettable. Bryce Walton is not one of my favorite pulp-era writers -- I've read a lot of his work for Planet. So is this story, about four criminals who escape in a spaceship heading for a paradise planet, one of four stars. They can't agree on the right planet, though, and come to violence over it (after they have crashed and are apparently traveling light years in their spacesuits). Horrid stuff.

Science Fiction Stories, 1953

Bryce Walton's "By Earthlight" (5200 words) is an anti-war story. The first flight to the Moon is planned, and a secret organization smuggles a man onto the ship (which is not meant to be manned). It's all part of an unconvincing attempt to end all war, by reasons explained in the story that I couldn't believe. It's a very sincere story, that tries to be a powerful message piece, but fizzles.

Vortex, Volume 1 Number 1

"The Last Answer", by Bryce Walton (4300 words) -- Computers and robots have taken over all man's functions and man is stagnating. A supercomputer decides that for the good of man this must change.

Planet Stories, Summer 1954

I read "Mary Anonymous", by Bryce Walton (7400 words) a few years ago in Planet Stories and didn't remember it before rereading it in Don Wollheim's anthology The Earth in Peril. It's not too bad -- Walton's stories didn't usually impress me much, but he could show some real ambition. Mars and Earth have been at war for decades, and Earth has just figured out the weapon to exterminate the Martians. But as they launch it, Mary suddenly rebels, and, as it turns out conditioned by the Martians, destroys the Earth spaceship. It's a surprisingly cynical story -- both Earth and Mars come off as irredeemably evil. Mary is sympathetic but does bad things too. The story ends with a twist revelation about Mary that seemed obvious to me (but then I had read the story before!)

Orbit, July-August 1954

"The Passion of Orpheus", by Bryce Walton (7500 words) -- probably the most ambitious of these stories, though not quite successful. After some disastrous nuclear wars, a small remnant of humanity survives. They remember the great days of life in the City. Finally, a representative young man is sent to the City, with instructions to go to the Temple and sing the Song, which may do something good but unspecified. Near the city he meets some beautiful but unambitious people, who try to keep him with him (using sex and all), but he continues to the City, sings the Song, and learns its real purpose, and the real nature of the people he has just been with. It doesn't convince, but it's not without interest -- Walton at something like the top of his not very extensive range.

If, June 1955

Bryce Walton's "Freeway" (5000 words) is a curious combination of the "people living in their cars all the time" story with the "oppressed intellectuals" story. Our hero and his wife are driving all the time, forbidden to stop for more than 8 hours at a time because he has been accused of "philosophy", and also of supporting the previous administration. His wife is sick, and he stops illegally, and he is pushed to violence, but then ... The setup is strained, and the resolution implausible.

If, October 1957

The other novelette (note that at If even stories over 20,000 words were still novelettes -- as I have noted elsewhere, Novella did not become a common term until much later, though Short Novel was not uncommon) was Bryce Walton's "Dark Windows". This concerns a future in which "eggheads" are blamed for all the world's problems. People have periodic intelligence tests, and are subject to destructive brain-probes if they fail -- or, I should say, pass! Our hero, Fred, a loyal patriot, is recruited to the SPA to help hunt down eggheads, partly because he is held to have well-suppressed intelligence. Well, you can see where this is going -- Fred will become an Egghead -- but Walton does get to a slightly unexpected ending.

In his honor, here's a look at several of his stories that I have read in various 1950s SF publications.

Space Science Fiction, May 1952

As for the other story, "To Each His Star", it's wholly forgettable. Bryce Walton is not one of my favorite pulp-era writers -- I've read a lot of his work for Planet. So is this story, about four criminals who escape in a spaceship heading for a paradise planet, one of four stars. They can't agree on the right planet, though, and come to violence over it (after they have crashed and are apparently traveling light years in their spacesuits). Horrid stuff.

Science Fiction Stories, 1953

Bryce Walton's "By Earthlight" (5200 words) is an anti-war story. The first flight to the Moon is planned, and a secret organization smuggles a man onto the ship (which is not meant to be manned). It's all part of an unconvincing attempt to end all war, by reasons explained in the story that I couldn't believe. It's a very sincere story, that tries to be a powerful message piece, but fizzles.

Vortex, Volume 1 Number 1

"The Last Answer", by Bryce Walton (4300 words) -- Computers and robots have taken over all man's functions and man is stagnating. A supercomputer decides that for the good of man this must change.

Planet Stories, Summer 1954

I read "Mary Anonymous", by Bryce Walton (7400 words) a few years ago in Planet Stories and didn't remember it before rereading it in Don Wollheim's anthology The Earth in Peril. It's not too bad -- Walton's stories didn't usually impress me much, but he could show some real ambition. Mars and Earth have been at war for decades, and Earth has just figured out the weapon to exterminate the Martians. But as they launch it, Mary suddenly rebels, and, as it turns out conditioned by the Martians, destroys the Earth spaceship. It's a surprisingly cynical story -- both Earth and Mars come off as irredeemably evil. Mary is sympathetic but does bad things too. The story ends with a twist revelation about Mary that seemed obvious to me (but then I had read the story before!)

Orbit, July-August 1954

"The Passion of Orpheus", by Bryce Walton (7500 words) -- probably the most ambitious of these stories, though not quite successful. After some disastrous nuclear wars, a small remnant of humanity survives. They remember the great days of life in the City. Finally, a representative young man is sent to the City, with instructions to go to the Temple and sing the Song, which may do something good but unspecified. Near the city he meets some beautiful but unambitious people, who try to keep him with him (using sex and all), but he continues to the City, sings the Song, and learns its real purpose, and the real nature of the people he has just been with. It doesn't convince, but it's not without interest -- Walton at something like the top of his not very extensive range.

If, June 1955

Bryce Walton's "Freeway" (5000 words) is a curious combination of the "people living in their cars all the time" story with the "oppressed intellectuals" story. Our hero and his wife are driving all the time, forbidden to stop for more than 8 hours at a time because he has been accused of "philosophy", and also of supporting the previous administration. His wife is sick, and he stops illegally, and he is pushed to violence, but then ... The setup is strained, and the resolution implausible.

If, October 1957

The other novelette (note that at If even stories over 20,000 words were still novelettes -- as I have noted elsewhere, Novella did not become a common term until much later, though Short Novel was not uncommon) was Bryce Walton's "Dark Windows". This concerns a future in which "eggheads" are blamed for all the world's problems. People have periodic intelligence tests, and are subject to destructive brain-probes if they fail -- or, I should say, pass! Our hero, Fred, a loyal patriot, is recruited to the SPA to help hunt down eggheads, partly because he is held to have well-suppressed intelligence. Well, you can see where this is going -- Fred will become an Egghead -- but Walton does get to a slightly unexpected ending.

Tuesday, May 26, 2020

Birthday Review: Stories of Caitlin R. Kiernan

Birthday Review: Stories of Caitlin R. Kiernan

Today is Caitlin R. Kiernan's birthday, and I find I've never published a collection of my reviews of her short fiction. So here is one!

Blog review of Shadows Over Baker Street, November 2003

"The Drowned Geologist", by Caitlín R. Kiernan, also only peripherally features Holmes, mostly telling of an American geologist who encounters some mysterious old fossils on a visit to England.

Blog review of Gothic!, April 2005

I quite enjoyed Caitlin R. Kiernan's "The Dead and the Moonstruck", another "reversal" story, this one about a changeling raised by ghouls who must pass a rite of passage test to become fully accepted by her new family. The story doesn't really go anywhere though -- it is clearly a bit of backgrounding for a character in her latest novel. But I did enjoy it.

Locus, December 2008

The opening and closing stories in the fine, typically rather mannered, small magazine Not One of Us (now up to 40 issues!) impressed me. Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “Flotsam” is a brief intense depiction of the protagonist’s latest encounter with a seductive vampire of sorts – it’s essentially a prose poem, and as such not easy to pull off, but Kiernan’s writing is lovely and it works.

Review of Eclipse 4 (Locus, May 2011)

“Tidal Forces” by Caitlin R. Kiernan is very well-written, and the central characters are utterly real, but its central conceit, which is purposely just plain weird, came off simply too affected for me. I have no doubt Kiernan did exactly as she intended, and used the idea with eyes fully open – but it didn’t work. There’s still plenty to like in this story of a woman whose partner is afflicted with a black hole, quite literally, that begins to eat her substance away.

Review of Supernatural Noir (Locus, August 2011)

And finally Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “The Maltese Unicorn”, which is as stylishly noir as any story here, about a used bookstore owner who is friendly with a mysterious brothel owner, and thus ends up trying to track down a strange object – a dildo – for her, and ends up getting involved, to her distress, with a beautiful and untrustworthy woman mixed up in the whole business. I thought this the best story in the book, and the story that most perfectly, to my taste, matched the theme.

Review of Naked City (Locus, August 2011)

The American West, and mines, are also central to another strong Caitlín R. Kiernan story, “The Colliers’ Venus (1893)”, in which a museum curator investigates a captured woman – a woman found encased in rock, while dealing as well with his own abortive relationship.

Today is Caitlin R. Kiernan's birthday, and I find I've never published a collection of my reviews of her short fiction. So here is one!

Blog review of Shadows Over Baker Street, November 2003

"The Drowned Geologist", by Caitlín R. Kiernan, also only peripherally features Holmes, mostly telling of an American geologist who encounters some mysterious old fossils on a visit to England.

Blog review of Gothic!, April 2005

I quite enjoyed Caitlin R. Kiernan's "The Dead and the Moonstruck", another "reversal" story, this one about a changeling raised by ghouls who must pass a rite of passage test to become fully accepted by her new family. The story doesn't really go anywhere though -- it is clearly a bit of backgrounding for a character in her latest novel. But I did enjoy it.

Locus, December 2008

The opening and closing stories in the fine, typically rather mannered, small magazine Not One of Us (now up to 40 issues!) impressed me. Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “Flotsam” is a brief intense depiction of the protagonist’s latest encounter with a seductive vampire of sorts – it’s essentially a prose poem, and as such not easy to pull off, but Kiernan’s writing is lovely and it works.

Review of Eclipse 4 (Locus, May 2011)

“Tidal Forces” by Caitlin R. Kiernan is very well-written, and the central characters are utterly real, but its central conceit, which is purposely just plain weird, came off simply too affected for me. I have no doubt Kiernan did exactly as she intended, and used the idea with eyes fully open – but it didn’t work. There’s still plenty to like in this story of a woman whose partner is afflicted with a black hole, quite literally, that begins to eat her substance away.

Review of Supernatural Noir (Locus, August 2011)

And finally Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “The Maltese Unicorn”, which is as stylishly noir as any story here, about a used bookstore owner who is friendly with a mysterious brothel owner, and thus ends up trying to track down a strange object – a dildo – for her, and ends up getting involved, to her distress, with a beautiful and untrustworthy woman mixed up in the whole business. I thought this the best story in the book, and the story that most perfectly, to my taste, matched the theme.

Review of Naked City (Locus, August 2011)

The American West, and mines, are also central to another strong Caitlín R. Kiernan story, “The Colliers’ Venus (1893)”, in which a museum curator investigates a captured woman – a woman found encased in rock, while dealing as well with his own abortive relationship.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)