Birthday Review: Stories of Caitlin R. Kiernan

Today is Caitlin R. Kiernan's birthday, and I find I've never published a collection of my reviews of her short fiction. So here is one!

Blog review of Shadows Over Baker Street, November 2003

"The Drowned Geologist", by Caitlín R. Kiernan, also only peripherally features Holmes, mostly telling of an American geologist who encounters some mysterious old fossils on a visit to England.

Blog review of Gothic!, April 2005

I quite enjoyed Caitlin R. Kiernan's "The Dead and the Moonstruck", another "reversal" story, this one about a changeling raised by ghouls who must pass a rite of passage test to become fully accepted by her new family. The story doesn't really go anywhere though -- it is clearly a bit of backgrounding for a character in her latest novel. But I did enjoy it.

Locus, December 2008

The opening and closing stories in the fine, typically rather mannered, small magazine Not One of Us (now up to 40 issues!) impressed me. Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “Flotsam” is a brief intense depiction of the protagonist’s latest encounter with a seductive vampire of sorts – it’s essentially a prose poem, and as such not easy to pull off, but Kiernan’s writing is lovely and it works.

Review of Eclipse 4 (Locus, May 2011)

“Tidal Forces” by Caitlin R. Kiernan is very well-written, and the central characters are utterly real, but its central conceit, which is purposely just plain weird, came off simply too affected for me. I have no doubt Kiernan did exactly as she intended, and used the idea with eyes fully open – but it didn’t work. There’s still plenty to like in this story of a woman whose partner is afflicted with a black hole, quite literally, that begins to eat her substance away.

Review of Supernatural Noir (Locus, August 2011)

And finally Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “The Maltese Unicorn”, which is as stylishly noir as any story here, about a used bookstore owner who is friendly with a mysterious brothel owner, and thus ends up trying to track down a strange object – a dildo – for her, and ends up getting involved, to her distress, with a beautiful and untrustworthy woman mixed up in the whole business. I thought this the best story in the book, and the story that most perfectly, to my taste, matched the theme.

Review of Naked City (Locus, August 2011)

The American West, and mines, are also central to another strong Caitlín R. Kiernan story, “The Colliers’ Venus (1893)”, in which a museum curator investigates a captured woman – a woman found encased in rock, while dealing as well with his own abortive relationship.

Tuesday, May 26, 2020

Old Bestseller: Franny and Zooey, by J. D. Salinger

Franny and Zooey, by J. D. Salinger

a review by Rich Horton

Franny and Zooey was J. D. Salinger's third book, published in 1961. The two previous books were his only novel (The Catcher in the Rye) and a story collection (Nine Stories.) The two parts of Franny and Zooey appeared in the New Yorker in 1955 and 1957.) It's a short book, and is usually described as comprising a short story ("Franny") and a novella ("Zooey".) In fact "Franny" is a longish short story at some 10,000 words by my rough count, and "Zooey" is a very long novella, perhaps 50,000 words. For that matter, the two pieces are intimately related, and if you ask me, they work together as a unified whole, and I think it makes a fair amount of sense to call the book a true novel.

This is the third Salinger book I've read. Like everyone else of my generation, I was assigned The Catcher in the Rye in high school, and like (it sometimes seems) only a few people, I rather liked it. I also read Nine Stories, and reread much of it just a few years ago. I think some of those stories are very fine. I could continue to the last book (Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters, and Seymour, an Introduction) but I am gathering that his work seemed to decline in quality as time went on, so perhaps I won't continue.

So I decided I'd read "Franny", because it's kind of short. And I read it through, liking it fine if not really loving it. It's the story of a few hours one weekend in which Franny comes up from her school (unspecified -- I thought it might be obvious to smarter readers but apparently it's not clear -- I'd have said maybe Vassar? maybe Mount Holyoke? but I don't know) to Harvard, where her boyfriend Lane goes, to attend the Harvard-Yale game. They go to a restaurant, and talk, and Franny is revealed as an interesting if a bit, well, immature young woman, while Lane is revealed as a prat (or "phony", Holden Caulfield would say.) Franny talks about books and her acting and about the odd book she's reading, The Way of the Pilgrim, about a man in Russia who is convinced that the way to spiritual truth is to continually recite a prayer: "Lord Jesus Christ have mercy on me". Franny doesn't eat and then gets sick. Lane mostly just gets mad that he's missing the game. By the end I was sure Franny was pregnant.

"Zooey" is set only a few days later, after Franny, in her delicate condition, has gone home to New York. It is basically organized around three communications between Zooey and his family -- first a long letter from his brother Buddy, next a long conversation in the bathroom with his mother, and then an even longer harangue (in a couple of parts) from Zooey to the distraught Franny. I kept waiting for the other shoe to drop about Franny's condition, but it never did, and eventually I realized Franny is NOT actually pregnant (though she probably was sleeping with the rather shallow Lane.) Instead she's having a spiritual crisis, based partly on her reaction to the book and its "prayer". Zooey, a TV actor, is unconvinced of the value of the book, and expresses some of his own philosophical notions, along with descriptions of his TV career, a couple of new scripts he's looking at, a potential movie he could appear in in France, and aspects of his family life. His and Franny's family, the Glasses, are Salinger's major fictional obsession -- the excellent story "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" features their older brother Seymour, who committed suicide. The children all appeared on a long-running radio show, which seems to have affected them in something like the way child actors are often depicted as being affected by early fame. Anyway, Zooey's ramblings (and really he does ramble) are sometimes interesting, somes just affected, to the point of occasional tedium. More to the point, he didn't really come to life for me, though Franny was a reasonably well done character.

I don't think this is a bad book, but it's not a great book either. It may be a book of its time ... probably it hit home a lot more directly in 1961 than now. I understand Salinger was quite upset that not just me but many readers assumed Franny was pregnant ... all I can say, it sure seemed like that's what we were expected to think. Salinger can (or could) write, but I think his prose was overrated at times ... it's original, has a real (though somewhat limited) voice, and certainly includes some sharp observation, but it never seemed quite striking to me, and sometimes just lost its way. Perhaps I write too much in awareness of where Salinger ended up ...

a review by Rich Horton

Franny and Zooey was J. D. Salinger's third book, published in 1961. The two previous books were his only novel (The Catcher in the Rye) and a story collection (Nine Stories.) The two parts of Franny and Zooey appeared in the New Yorker in 1955 and 1957.) It's a short book, and is usually described as comprising a short story ("Franny") and a novella ("Zooey".) In fact "Franny" is a longish short story at some 10,000 words by my rough count, and "Zooey" is a very long novella, perhaps 50,000 words. For that matter, the two pieces are intimately related, and if you ask me, they work together as a unified whole, and I think it makes a fair amount of sense to call the book a true novel.

This is the third Salinger book I've read. Like everyone else of my generation, I was assigned The Catcher in the Rye in high school, and like (it sometimes seems) only a few people, I rather liked it. I also read Nine Stories, and reread much of it just a few years ago. I think some of those stories are very fine. I could continue to the last book (Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters, and Seymour, an Introduction) but I am gathering that his work seemed to decline in quality as time went on, so perhaps I won't continue.

So I decided I'd read "Franny", because it's kind of short. And I read it through, liking it fine if not really loving it. It's the story of a few hours one weekend in which Franny comes up from her school (unspecified -- I thought it might be obvious to smarter readers but apparently it's not clear -- I'd have said maybe Vassar? maybe Mount Holyoke? but I don't know) to Harvard, where her boyfriend Lane goes, to attend the Harvard-Yale game. They go to a restaurant, and talk, and Franny is revealed as an interesting if a bit, well, immature young woman, while Lane is revealed as a prat (or "phony", Holden Caulfield would say.) Franny talks about books and her acting and about the odd book she's reading, The Way of the Pilgrim, about a man in Russia who is convinced that the way to spiritual truth is to continually recite a prayer: "Lord Jesus Christ have mercy on me". Franny doesn't eat and then gets sick. Lane mostly just gets mad that he's missing the game. By the end I was sure Franny was pregnant.

"Zooey" is set only a few days later, after Franny, in her delicate condition, has gone home to New York. It is basically organized around three communications between Zooey and his family -- first a long letter from his brother Buddy, next a long conversation in the bathroom with his mother, and then an even longer harangue (in a couple of parts) from Zooey to the distraught Franny. I kept waiting for the other shoe to drop about Franny's condition, but it never did, and eventually I realized Franny is NOT actually pregnant (though she probably was sleeping with the rather shallow Lane.) Instead she's having a spiritual crisis, based partly on her reaction to the book and its "prayer". Zooey, a TV actor, is unconvinced of the value of the book, and expresses some of his own philosophical notions, along with descriptions of his TV career, a couple of new scripts he's looking at, a potential movie he could appear in in France, and aspects of his family life. His and Franny's family, the Glasses, are Salinger's major fictional obsession -- the excellent story "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" features their older brother Seymour, who committed suicide. The children all appeared on a long-running radio show, which seems to have affected them in something like the way child actors are often depicted as being affected by early fame. Anyway, Zooey's ramblings (and really he does ramble) are sometimes interesting, somes just affected, to the point of occasional tedium. More to the point, he didn't really come to life for me, though Franny was a reasonably well done character.

I don't think this is a bad book, but it's not a great book either. It may be a book of its time ... probably it hit home a lot more directly in 1961 than now. I understand Salinger was quite upset that not just me but many readers assumed Franny was pregnant ... all I can say, it sure seemed like that's what we were expected to think. Salinger can (or could) write, but I think his prose was overrated at times ... it's original, has a real (though somewhat limited) voice, and certainly includes some sharp observation, but it never seemed quite striking to me, and sometimes just lost its way. Perhaps I write too much in awareness of where Salinger ended up ...

Sunday, May 10, 2020

Birthday Review: The Sorcerer's House, by Gene Wolfe

Gene Wolfe would have turned 89 this past Thursday. Alas, he died last year. I am (belatedly) posting another one of my reviews in his honor. This is perhaps the best of his late novels, The Sorcerer's House, from 2010. This review originally appeared in Fantasy Magazine.

The Sorcerer’s House

By Gene Wolfe

Tor

$24.99 | hc | 302 pages

ISBN: 978-0-7653-2458-0

March 2010

A review by Rich Horton

Gene Wolfe continues to publish interesting novels about every year. His new book is The Sorcerer’s House. It is a standalone novel, and, by Wolfe’s standards, a fairly simple one. It is also quite absorbing, a very nice read, and for all its relative “simplicity” stuffed with puzzles and with such Wolfean obsessions as twins, shapechanging, and virtue. And it is told in the familiar almost naïve first-person prose of many recent Wolfe novels.

The protagonist is Baxter Dunn, who has just been released from prison. We slowly gather that he went to jail for fraud, and that his victim, or one of his victims, was his identical twin brother, George. Most of the book is told in letters from Baxter to George, though Baxter also writes to George’s wife Millie, and to a friend he made in prison. And some of the letters here are addressed to Baxter.

Baxter comes to a quiet Midwestern town called Medicine Man. At first destitute, he comes by mysterious means into possession of a house called the Black House, which is rumored to be haunted. The house is quite odd – it is (of course) bigger on the inside than the outside, and its windows sometimes seem to look out on a landscape different that what one sees from the outside. And there are a variety of unusual characters attached to the house: another pair of good/bad twins, teenaged boys named Emlyn and Ieuan; a couple of weird butlers named Nicholas or Nick; a fox who sometimes seems to be a woman; and some magical implements.

Baxter also has encounters in the town, particular a series of variously interesting women: an attractive young widow, the older woman who revealed his inheritance to Baxter, a pert policewoman, etc. And the town is also menaced by a “Hellhound”. We are left to wonder what is really going on. Is Baxter really a criminal or did his brother betray him (perhaps because they both seem to love Millie)? Why did the mysterious Mr. Black leave his house to Baxter? From whence do all the odd creatures attracted to Baxter come – the fox woman, the werewolves, a vampire?

All this is familiar territory for Gene Wolfe’s readers. What may seem unusual is how relatively transparently it is all resolved. (Though the ending does leave a couple of open questions – I have my own answers, contradicting the plain narrative, but I’m by no means sure I’m right.) At any rate, it doesn’t quite achieve the depth of Wolfe’s very best work. But it avoids the frustration of a novel like, say, Castleview, at least to this reader, who knew there was something special going on beneath that book’s surface, but never quite figured it out. The Sorcerer’s House is, in the end, an entertainment, clever and satisfying – not great Wolfe, but good Wolfe, which is recommendation enough.

The Sorcerer’s House

By Gene Wolfe

Tor

$24.99 | hc | 302 pages

ISBN: 978-0-7653-2458-0

March 2010

A review by Rich Horton

Gene Wolfe continues to publish interesting novels about every year. His new book is The Sorcerer’s House. It is a standalone novel, and, by Wolfe’s standards, a fairly simple one. It is also quite absorbing, a very nice read, and for all its relative “simplicity” stuffed with puzzles and with such Wolfean obsessions as twins, shapechanging, and virtue. And it is told in the familiar almost naïve first-person prose of many recent Wolfe novels.

The protagonist is Baxter Dunn, who has just been released from prison. We slowly gather that he went to jail for fraud, and that his victim, or one of his victims, was his identical twin brother, George. Most of the book is told in letters from Baxter to George, though Baxter also writes to George’s wife Millie, and to a friend he made in prison. And some of the letters here are addressed to Baxter.

Baxter comes to a quiet Midwestern town called Medicine Man. At first destitute, he comes by mysterious means into possession of a house called the Black House, which is rumored to be haunted. The house is quite odd – it is (of course) bigger on the inside than the outside, and its windows sometimes seem to look out on a landscape different that what one sees from the outside. And there are a variety of unusual characters attached to the house: another pair of good/bad twins, teenaged boys named Emlyn and Ieuan; a couple of weird butlers named Nicholas or Nick; a fox who sometimes seems to be a woman; and some magical implements.

Baxter also has encounters in the town, particular a series of variously interesting women: an attractive young widow, the older woman who revealed his inheritance to Baxter, a pert policewoman, etc. And the town is also menaced by a “Hellhound”. We are left to wonder what is really going on. Is Baxter really a criminal or did his brother betray him (perhaps because they both seem to love Millie)? Why did the mysterious Mr. Black leave his house to Baxter? From whence do all the odd creatures attracted to Baxter come – the fox woman, the werewolves, a vampire?

All this is familiar territory for Gene Wolfe’s readers. What may seem unusual is how relatively transparently it is all resolved. (Though the ending does leave a couple of open questions – I have my own answers, contradicting the plain narrative, but I’m by no means sure I’m right.) At any rate, it doesn’t quite achieve the depth of Wolfe’s very best work. But it avoids the frustration of a novel like, say, Castleview, at least to this reader, who knew there was something special going on beneath that book’s surface, but never quite figured it out. The Sorcerer’s House is, in the end, an entertainment, clever and satisfying – not great Wolfe, but good Wolfe, which is recommendation enough.

Monday, May 4, 2020

Birthday Review: Leviathan, by Scott Westerfeld

Here's a review in honor of Scott Westerfeld's birthday, today -- his very enjoyable Steampunk YA novel Leviathan.

Leviathan

by Scott Westerfeld

Simon Pulse

$19.99 | hc | 440 pages

ISBN: 978-1-4169-7173-3

October 2009

A review by Rich Horton

Scott Westerfeld’s Leviathan is a thoroughly delightful Young Adult novel, the first in a series that is based on World War I, but in an alternate history. In this history Charles Darwin discovered the genetic basis for evolution, and how to manipulate it, and as a result the United Kingdom and its allies have a society based on biotechnology, such as the title airship, a huge beast (or colony of organisms) based on whale DNA and much more. By contrast the Germans and Austrians and their allies, called Clankers, use Steampunk flavored machinery: airplanes and zeppelins, but also great walking land war machines.

The novel is told through the point of view of two teens. Aleksandar is the son of the murdered Serbian Prince Franz Ferdinand and his lower-class wife, and as such is not eligible for the throne, but is still a threat to the powers that be. As the novel opens he is spirited away by a pair of loyal retainers, who fear that the people who arranged for Alek’s parents to be killed will be coming for him. They take a smallish “Walker” and head for Switzerland, fleeing the German army that should be on their side. Meanwhile Deryn Sharp, a girl who has grown up loving to fly the living balloons based on jellyfish genetics, has disguised herself as a boy and joined the Air Service. She ends up a midshipman on the whale-based Leviathan, which is ferrying a valuable but mysterious cargo from England to Turkey, just as war is breaking out.

As we might expect their paths cross … And, in reality, nothing is resolved in this book, no mysteries even unveiled. That will wait for subsequent books, which this reader anticpates eagerly.

The novel is in many ways a familiar YA construction: a hidden Prince, a disguised girl, both people who need to grow up and are being forced to do so in a dangerous situation. The book delights in part because both protagonists are nicely depicted and fun to follow and root for. It also delights in the depiction of the rival, unusual, technologies of the Darwinists and the Clankers. Westerfeld is very good with plausible invented words, and with plausible (to a sufficient degree, at least) inventions, particularly his biological inventions. (The Clanker tech, after all, though different to ours, is still by and large familiar.) There is plenty of exciting action as well. And an intriguing mystery – with the hint that the War may play out a bit differently than in our world – which hold the interest in this book and make subsequent books much to be looked forward to.

Leviathan

by Scott Westerfeld

Simon Pulse

$19.99 | hc | 440 pages

ISBN: 978-1-4169-7173-3

October 2009

A review by Rich Horton

Scott Westerfeld’s Leviathan is a thoroughly delightful Young Adult novel, the first in a series that is based on World War I, but in an alternate history. In this history Charles Darwin discovered the genetic basis for evolution, and how to manipulate it, and as a result the United Kingdom and its allies have a society based on biotechnology, such as the title airship, a huge beast (or colony of organisms) based on whale DNA and much more. By contrast the Germans and Austrians and their allies, called Clankers, use Steampunk flavored machinery: airplanes and zeppelins, but also great walking land war machines.

The novel is told through the point of view of two teens. Aleksandar is the son of the murdered Serbian Prince Franz Ferdinand and his lower-class wife, and as such is not eligible for the throne, but is still a threat to the powers that be. As the novel opens he is spirited away by a pair of loyal retainers, who fear that the people who arranged for Alek’s parents to be killed will be coming for him. They take a smallish “Walker” and head for Switzerland, fleeing the German army that should be on their side. Meanwhile Deryn Sharp, a girl who has grown up loving to fly the living balloons based on jellyfish genetics, has disguised herself as a boy and joined the Air Service. She ends up a midshipman on the whale-based Leviathan, which is ferrying a valuable but mysterious cargo from England to Turkey, just as war is breaking out.

As we might expect their paths cross … And, in reality, nothing is resolved in this book, no mysteries even unveiled. That will wait for subsequent books, which this reader anticpates eagerly.

The novel is in many ways a familiar YA construction: a hidden Prince, a disguised girl, both people who need to grow up and are being forced to do so in a dangerous situation. The book delights in part because both protagonists are nicely depicted and fun to follow and root for. It also delights in the depiction of the rival, unusual, technologies of the Darwinists and the Clankers. Westerfeld is very good with plausible invented words, and with plausible (to a sufficient degree, at least) inventions, particularly his biological inventions. (The Clanker tech, after all, though different to ours, is still by and large familiar.) There is plenty of exciting action as well. And an intriguing mystery – with the hint that the War may play out a bit differently than in our world – which hold the interest in this book and make subsequent books much to be looked forward to.

Review: The Sky So Big and Black, by John Barnes

The Sky So Big and Black, by John Barnes

a review by Rich Horton

This is John Barnes' new novel. It's set in the same future history as his novels Orbital Resonance, Kaleidoscope Century, and Candle. Like Orbital Resonance, it's nominally YA, and very Heinleinian, and very much "to please adults". It's something of a sequel to Orbital Resonance -- I don't remember that book that well, but I'm pretty sure the main character of the new book is a relative of the main character of the older book -- I think a niece. It's also heavily related to Candle, far as I can tell, in that a main plot element is the takeover of Earth by the "One True" meme -- something I deduce happened in Candle, though I'm not quite sure. (I haven't read Candle.) (I say "Future History" but it's really an odd variant -- a sort of Future Alternate History, in that it's set in a future that branches from a near past (at time of writing) history that never happened.)

I just wanted basically to say that I loved this book. As I mention, it's very much in the Heinlein Juvenile mode. There are passages that seem pure quill Heinlein. Here's the protagonist's father and her talking about education in the 20th Century:

"In fact what [20th C. students] got was either a specialty in some academic subject, like math or literature, or certification in some useful trade, like engineering or lying."

"They didn't have certification in lying!"

"Ha! The first place my grandpa taught was a program in something called "communications". Look up the curriculum sometime and tell me that's not a degree in lying!"

And there's plenty more in that vein, about personal responsibility and politics and human relationships.

But more than all that, it's just a good novel. Very well structured -- it's presented as a psychologist listening to a series of interviews he did with Teri-Mel Murray, a young woman on Mars who was working with her father as an "ecospector". It's clear from the start that something terrible happened, and indeed that the psychologist was forced to erase Teri-Mel's memory. It's also clear that he likes her a lot, and is really torn up by what has happened, and worried that he may have to treat her again, for some mysterious reason that takes a long time to become clear.

The interviews tell of Teri and her father travelling across the lightly terraformed planet to a "Gather" of the "rounditachis", people who live more or less in the open on Mars, working to help advance the terraforming. Teri is hoping that she will be certified a "Full Adult" at the Gather, and be free to marry her boyfriend. Her father wants her to go back to school for one more year, because he's not convinced that ecospecting will remain a good living. As they travel, they plan to make one more attempt at a big "scorehole". And Teri is starting to worry about her boyfriend.

All the above is cute stuff, and interleaved with neat SFnal details about the terraforming of Mars. In the background lurk details about the future history up to this point, especially the takeover of ecologically ravaged Earth by a "meme" called "One True", or "Resuna", which more or less has turned Earth's population into a hive mind. Also we learn bits and pieces about the psychologist's feelings, which give us hints about the disaster which has clearly occurred.

So it's a scary book, as we learn to like Teri more and more, while we just know that she's going to get hurt real real bad. And when the crisis comes, it's exciting, and terribly sad, and even scarier than I had first expected.

The resolution is moving, real, and, well, open. Barnes' future is on the one hand full of hope, and of cool SFnal stuff, and on the other hand it is very damned scary, and full of something purely evil, but not EVULL, somehow.

It's a darn good novel, and though it is written about a "young adult" (Teri is about 15), and though it is accessible and readable and appropriate (in my judgement) for teens to read, it is also very effective for adults.

a review by Rich Horton

This is John Barnes' new novel. It's set in the same future history as his novels Orbital Resonance, Kaleidoscope Century, and Candle. Like Orbital Resonance, it's nominally YA, and very Heinleinian, and very much "to please adults". It's something of a sequel to Orbital Resonance -- I don't remember that book that well, but I'm pretty sure the main character of the new book is a relative of the main character of the older book -- I think a niece. It's also heavily related to Candle, far as I can tell, in that a main plot element is the takeover of Earth by the "One True" meme -- something I deduce happened in Candle, though I'm not quite sure. (I haven't read Candle.) (I say "Future History" but it's really an odd variant -- a sort of Future Alternate History, in that it's set in a future that branches from a near past (at time of writing) history that never happened.)

I just wanted basically to say that I loved this book. As I mention, it's very much in the Heinlein Juvenile mode. There are passages that seem pure quill Heinlein. Here's the protagonist's father and her talking about education in the 20th Century:

"In fact what [20th C. students] got was either a specialty in some academic subject, like math or literature, or certification in some useful trade, like engineering or lying."

"They didn't have certification in lying!"

"Ha! The first place my grandpa taught was a program in something called "communications". Look up the curriculum sometime and tell me that's not a degree in lying!"

And there's plenty more in that vein, about personal responsibility and politics and human relationships.

But more than all that, it's just a good novel. Very well structured -- it's presented as a psychologist listening to a series of interviews he did with Teri-Mel Murray, a young woman on Mars who was working with her father as an "ecospector". It's clear from the start that something terrible happened, and indeed that the psychologist was forced to erase Teri-Mel's memory. It's also clear that he likes her a lot, and is really torn up by what has happened, and worried that he may have to treat her again, for some mysterious reason that takes a long time to become clear.

The interviews tell of Teri and her father travelling across the lightly terraformed planet to a "Gather" of the "rounditachis", people who live more or less in the open on Mars, working to help advance the terraforming. Teri is hoping that she will be certified a "Full Adult" at the Gather, and be free to marry her boyfriend. Her father wants her to go back to school for one more year, because he's not convinced that ecospecting will remain a good living. As they travel, they plan to make one more attempt at a big "scorehole". And Teri is starting to worry about her boyfriend.

All the above is cute stuff, and interleaved with neat SFnal details about the terraforming of Mars. In the background lurk details about the future history up to this point, especially the takeover of ecologically ravaged Earth by a "meme" called "One True", or "Resuna", which more or less has turned Earth's population into a hive mind. Also we learn bits and pieces about the psychologist's feelings, which give us hints about the disaster which has clearly occurred.

So it's a scary book, as we learn to like Teri more and more, while we just know that she's going to get hurt real real bad. And when the crisis comes, it's exciting, and terribly sad, and even scarier than I had first expected.

The resolution is moving, real, and, well, open. Barnes' future is on the one hand full of hope, and of cool SFnal stuff, and on the other hand it is very damned scary, and full of something purely evil, but not EVULL, somehow.

It's a darn good novel, and though it is written about a "young adult" (Teri is about 15), and though it is accessible and readable and appropriate (in my judgement) for teens to read, it is also very effective for adults.

Friday, May 1, 2020

Birthday Review: Naomi Novik's first three Temeraire books, plus some short fiction

Naomi Novik was born on the last day of April, so in honor of her birthday, here are some reviews I have done of her (excellent) work, the first a review of the first three Temeraire novels from Black Gate, and then a few reviews of short fiction for Locus.

His Majesty's Dragon/Throne of Jade/Black Powder War

by Naomi Novik. Del Rey, $7.50 each (384/432/400p)

ISBNS: 0345481283 / 0345481291 / 0345481305

March/April/May 2006.

A Review by Rich Horton (Black Gate, Spring 2007)

These three books are the first of a potentially open-ended series [it did, of course, eventually come to completion -- the first 8 covers are shown here, the ninth book, League of Dragons, came out in 2016, and there is also a story collection], set during the Napoleonic Wars in an alternate fantastical past: almost exactly like our history but with dragons. The obvious comparison is with Patrick O'Brian, and it is a high compliment indeed to say that the books are not entirely unworthy of such company as O'Brian's Aubrey/Maturin novels of the British Navy during the Napoleonic Wars (which some consider the best historical novel series ever.) I found Novik's books extremely enjoyable reading, and I look forward to many further volumes. Del Rey's interesting publishing strategy, issuing three books in very quick succession, has evidently garnered Novik and the books well-deserved sales and public attention.

It should be noted that the novels are indeed true series novels: each concluding its sub-story satisfyingly enough, but also advancing an overall arc. The series opens with Captain Will Laurence of the English Navy capturing a French ship, on which there is a dragon egg. When dragons hatch they are "harnessed" by a person who will be their constant companion: usually an aviator, but no such candidate being available the man chosen is Laurence himself. This means the end of his promising Naval career, and an unconventional life as one of the rather raffish Aerial Corps, but the friendship of the dragon, a very unusual specimen he names Temeraire, proves to be ample compensation. His Majesty's Dragon (titled Temeraire in the UK) details the training of Laurence and Temeraire, complete with some internal conflicts and adjustments, leading to their first battles and the revelation of Temeraire's particularly special war-fighting power, unique to his variety of extremely rare dragon. This variety, it transpires, is the Chinese Celestial, usually reserved to be companions of the Chinese Imperial Family.

In Throne of Jade the Chinese protest the British capture of Temeraire (who had been intended as a gift for Napoleon), and the spineless Foreign Office sends Laurence, Temeraire, and crew to China, hoping to negotiate better trading rights in exchange for returning this valuable dragon. But while Temeraire enjoys China, in particular the special privileges -- or, perhaps, ordinary rights that all intelligent creatures ought to enjoy -- given dragons there, he refuses to be separated from Laurence. Also, it turns out there is some political turmoil in China -- the resolution of which leads also to an accommodation that allows Laurence and Temeraire to remain together.

Black Powder War is the story of their desperate land journey first to Istanbul, to collect three more dragon eggs the British have bought from the Turks, then through war-torn Europe, where they learn that Napoleon has a new Celestial -- one who has cause to hate Laurence, Temeraire, and by extension England.

The first book is nearly an unalloyed delight (save the slightly unprepared-for nature of the end), the second is enjoyable but a step down, perhaps a bit too slow; and the third ranks pretty much with the second, though the ending is surprising and quite moving. The series as a whole promises to continue to be very fun reading, with a nicely set up tension between the necessity of defeating Napoleon and the cause of "Dragon's Rights", which Temeraire has at last persuaded Laurence is both morally and practically essential. Both lead characters are engaging and well-depicted, the prose is nicely handled with a sound period flavor, the fantastical elements are not terribly plausible (nor necessarily consistent) but they (draconic characteristics and types, basically) are nicely imagined. Recommended.

Review of Fast Ships, Black Sails (Locus, December 2008)

One coup the VanderMeers managed was to land a novelette from Naomi Novik. (To my knowledge she has only published two other short stories, both quite short, at her website.) “Araminta; or, The Wreck of the Amphidrake” is one of the best pieces in this book. It’s not a Temeraire story -- it is a gender-bending tale of a rather tomboyish girl of a noble family sent by sea to marry the young man her parents have chosen. When pirates attack her ship, she resorts to a special magical protection she has been given … the results are entertaining and in the end Araminta gets the chance to make her own choices for her future, choices that not too surprisingly involve adventure and piracy.

Review of Warriors (Locus, May 2010)

Naomi Novik shows up with her first straight SF story (that I know of), “Seven Years From Home”, about a diplomat sent to an alien planet, charged with mediating somehow between two human variant groups, one of which has colonized one continent by altering themselves to blend in with the established ecology, the other of which, latecomers, are bent on terraforming the planet, and having conquered their continent are now proceeding to the other. The diplomat, not surprisingly, goes native (as it were), only to become complicit in what she can’t help seeing a terrible crime. The story has some intriguing elements, but doesn’t really convince. But it’s nice to see Novik continue to extend her range – she is serving notice that she won’t be tied to Temeraire for her whole career.

Review of Naked City (Locus, August 2011)

More lighthearted are stories like Naomi Novik’s “Priced to Sell”, about various problems a real estate agent deals with in selling to the magical community – slight, to be sure, but fun.

Locus, January 2017

One of my favorite stories in The Starlit Wood is Naomi Novik’s “Spinning Silver”. As one might guess, Rumpelstiltskin in the base story. The conceit is that instead of spinning straw into gold, a moneylender might be seen as spinning silver (a small amount of money) into a larger amount (gold). The narrator is the daughter of a poor village moneylender, too kindly to make a living. The daughter, however, has learned to harden her heart to her father’s clients’ troubles – which often enough are invented anyway – and under her stewardship the family has prospered – but at what cost? Especially when a fairy creature called the Staryk learns of her abilities, and insists that she spin his silver into gold. The mechanism she uses is clever, and the expected complications ensue, especially when the local Duke is involved. Novik very effectively layers the story with meaning – most notably the status of the moneylenders, who are (of course) Jewish – which points as well to a perhaps sometimes missed element of Rumpelstiltskin’s traditional portrayal. As with many of the stories in this book (and indeed in most contemporary fairy tale versions) the agency or lack thereof of the female characters is also central, and quite matter of factly and honestly treated.

His Majesty's Dragon/Throne of Jade/Black Powder War

by Naomi Novik. Del Rey, $7.50 each (384/432/400p)

ISBNS: 0345481283 / 0345481291 / 0345481305

March/April/May 2006.

A Review by Rich Horton (Black Gate, Spring 2007)

These three books are the first of a potentially open-ended series [it did, of course, eventually come to completion -- the first 8 covers are shown here, the ninth book, League of Dragons, came out in 2016, and there is also a story collection], set during the Napoleonic Wars in an alternate fantastical past: almost exactly like our history but with dragons. The obvious comparison is with Patrick O'Brian, and it is a high compliment indeed to say that the books are not entirely unworthy of such company as O'Brian's Aubrey/Maturin novels of the British Navy during the Napoleonic Wars (which some consider the best historical novel series ever.) I found Novik's books extremely enjoyable reading, and I look forward to many further volumes. Del Rey's interesting publishing strategy, issuing three books in very quick succession, has evidently garnered Novik and the books well-deserved sales and public attention.

It should be noted that the novels are indeed true series novels: each concluding its sub-story satisfyingly enough, but also advancing an overall arc. The series opens with Captain Will Laurence of the English Navy capturing a French ship, on which there is a dragon egg. When dragons hatch they are "harnessed" by a person who will be their constant companion: usually an aviator, but no such candidate being available the man chosen is Laurence himself. This means the end of his promising Naval career, and an unconventional life as one of the rather raffish Aerial Corps, but the friendship of the dragon, a very unusual specimen he names Temeraire, proves to be ample compensation. His Majesty's Dragon (titled Temeraire in the UK) details the training of Laurence and Temeraire, complete with some internal conflicts and adjustments, leading to their first battles and the revelation of Temeraire's particularly special war-fighting power, unique to his variety of extremely rare dragon. This variety, it transpires, is the Chinese Celestial, usually reserved to be companions of the Chinese Imperial Family.

In Throne of Jade the Chinese protest the British capture of Temeraire (who had been intended as a gift for Napoleon), and the spineless Foreign Office sends Laurence, Temeraire, and crew to China, hoping to negotiate better trading rights in exchange for returning this valuable dragon. But while Temeraire enjoys China, in particular the special privileges -- or, perhaps, ordinary rights that all intelligent creatures ought to enjoy -- given dragons there, he refuses to be separated from Laurence. Also, it turns out there is some political turmoil in China -- the resolution of which leads also to an accommodation that allows Laurence and Temeraire to remain together.

Black Powder War is the story of their desperate land journey first to Istanbul, to collect three more dragon eggs the British have bought from the Turks, then through war-torn Europe, where they learn that Napoleon has a new Celestial -- one who has cause to hate Laurence, Temeraire, and by extension England.

The first book is nearly an unalloyed delight (save the slightly unprepared-for nature of the end), the second is enjoyable but a step down, perhaps a bit too slow; and the third ranks pretty much with the second, though the ending is surprising and quite moving. The series as a whole promises to continue to be very fun reading, with a nicely set up tension between the necessity of defeating Napoleon and the cause of "Dragon's Rights", which Temeraire has at last persuaded Laurence is both morally and practically essential. Both lead characters are engaging and well-depicted, the prose is nicely handled with a sound period flavor, the fantastical elements are not terribly plausible (nor necessarily consistent) but they (draconic characteristics and types, basically) are nicely imagined. Recommended.

Review of Fast Ships, Black Sails (Locus, December 2008)

One coup the VanderMeers managed was to land a novelette from Naomi Novik. (To my knowledge she has only published two other short stories, both quite short, at her website.) “Araminta; or, The Wreck of the Amphidrake” is one of the best pieces in this book. It’s not a Temeraire story -- it is a gender-bending tale of a rather tomboyish girl of a noble family sent by sea to marry the young man her parents have chosen. When pirates attack her ship, she resorts to a special magical protection she has been given … the results are entertaining and in the end Araminta gets the chance to make her own choices for her future, choices that not too surprisingly involve adventure and piracy.

Review of Warriors (Locus, May 2010)

Naomi Novik shows up with her first straight SF story (that I know of), “Seven Years From Home”, about a diplomat sent to an alien planet, charged with mediating somehow between two human variant groups, one of which has colonized one continent by altering themselves to blend in with the established ecology, the other of which, latecomers, are bent on terraforming the planet, and having conquered their continent are now proceeding to the other. The diplomat, not surprisingly, goes native (as it were), only to become complicit in what she can’t help seeing a terrible crime. The story has some intriguing elements, but doesn’t really convince. But it’s nice to see Novik continue to extend her range – she is serving notice that she won’t be tied to Temeraire for her whole career.

Review of Naked City (Locus, August 2011)

More lighthearted are stories like Naomi Novik’s “Priced to Sell”, about various problems a real estate agent deals with in selling to the magical community – slight, to be sure, but fun.

Locus, January 2017

One of my favorite stories in The Starlit Wood is Naomi Novik’s “Spinning Silver”. As one might guess, Rumpelstiltskin in the base story. The conceit is that instead of spinning straw into gold, a moneylender might be seen as spinning silver (a small amount of money) into a larger amount (gold). The narrator is the daughter of a poor village moneylender, too kindly to make a living. The daughter, however, has learned to harden her heart to her father’s clients’ troubles – which often enough are invented anyway – and under her stewardship the family has prospered – but at what cost? Especially when a fairy creature called the Staryk learns of her abilities, and insists that she spin his silver into gold. The mechanism she uses is clever, and the expected complications ensue, especially when the local Duke is involved. Novik very effectively layers the story with meaning – most notably the status of the moneylenders, who are (of course) Jewish – which points as well to a perhaps sometimes missed element of Rumpelstiltskin’s traditional portrayal. As with many of the stories in this book (and indeed in most contemporary fairy tale versions) the agency or lack thereof of the female characters is also central, and quite matter of factly and honestly treated.

Friday, April 24, 2020

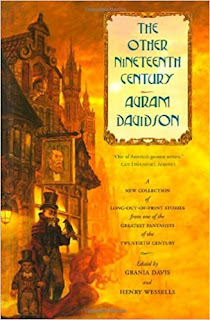

Birthday Review: The Other Nineteenth Century, by Avram Davidson

This is slightly belated -- Avram Davidson would have turned 97 yesterday. Gosh, he was a wonderful writer! I've previously covered a couple of his Ace Doubles, and I've posted a survey of his novels, and a review of The Avram Davidson Treasury, so here's a very short bit I wrote for my blog some long while ago about another posthumous collection, The Other Nineteenth Century.

[On reflection, I've regretted posting that rather casually tossed off old blog entry, and I've produced a more thorough review here:

Review of The Other Nineteenth Century.]

[On reflection, I've regretted posting that rather casually tossed off old blog entry, and I've produced a more thorough review here:

Review of The Other Nineteenth Century.]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)