Gene Wolfe would have turned 89 this past Thursday. Alas, he died last year. I am (belatedly) posting another one of my reviews in his honor. This is perhaps the best of his late novels, The Sorcerer's House, from 2010. This review originally appeared in Fantasy Magazine.

The Sorcerer’s House

By Gene Wolfe

Tor

$24.99 | hc | 302 pages

ISBN: 978-0-7653-2458-0

March 2010

A review by Rich Horton

Gene Wolfe continues to publish interesting novels about every year. His new book is The Sorcerer’s House. It is a standalone novel, and, by Wolfe’s standards, a fairly simple one. It is also quite absorbing, a very nice read, and for all its relative “simplicity” stuffed with puzzles and with such Wolfean obsessions as twins, shapechanging, and virtue. And it is told in the familiar almost naïve first-person prose of many recent Wolfe novels.

The protagonist is Baxter Dunn, who has just been released from prison. We slowly gather that he went to jail for fraud, and that his victim, or one of his victims, was his identical twin brother, George. Most of the book is told in letters from Baxter to George, though Baxter also writes to George’s wife Millie, and to a friend he made in prison. And some of the letters here are addressed to Baxter.

Baxter comes to a quiet Midwestern town called Medicine Man. At first destitute, he comes by mysterious means into possession of a house called the Black House, which is rumored to be haunted. The house is quite odd – it is (of course) bigger on the inside than the outside, and its windows sometimes seem to look out on a landscape different that what one sees from the outside. And there are a variety of unusual characters attached to the house: another pair of good/bad twins, teenaged boys named Emlyn and Ieuan; a couple of weird butlers named Nicholas or Nick; a fox who sometimes seems to be a woman; and some magical implements.

Baxter also has encounters in the town, particular a series of variously interesting women: an attractive young widow, the older woman who revealed his inheritance to Baxter, a pert policewoman, etc. And the town is also menaced by a “Hellhound”. We are left to wonder what is really going on. Is Baxter really a criminal or did his brother betray him (perhaps because they both seem to love Millie)? Why did the mysterious Mr. Black leave his house to Baxter? From whence do all the odd creatures attracted to Baxter come – the fox woman, the werewolves, a vampire?

All this is familiar territory for Gene Wolfe’s readers. What may seem unusual is how relatively transparently it is all resolved. (Though the ending does leave a couple of open questions – I have my own answers, contradicting the plain narrative, but I’m by no means sure I’m right.) At any rate, it doesn’t quite achieve the depth of Wolfe’s very best work. But it avoids the frustration of a novel like, say, Castleview, at least to this reader, who knew there was something special going on beneath that book’s surface, but never quite figured it out. The Sorcerer’s House is, in the end, an entertainment, clever and satisfying – not great Wolfe, but good Wolfe, which is recommendation enough.

Sunday, May 10, 2020

Monday, May 4, 2020

Birthday Review: Leviathan, by Scott Westerfeld

Here's a review in honor of Scott Westerfeld's birthday, today -- his very enjoyable Steampunk YA novel Leviathan.

Leviathan

by Scott Westerfeld

Simon Pulse

$19.99 | hc | 440 pages

ISBN: 978-1-4169-7173-3

October 2009

A review by Rich Horton

Scott Westerfeld’s Leviathan is a thoroughly delightful Young Adult novel, the first in a series that is based on World War I, but in an alternate history. In this history Charles Darwin discovered the genetic basis for evolution, and how to manipulate it, and as a result the United Kingdom and its allies have a society based on biotechnology, such as the title airship, a huge beast (or colony of organisms) based on whale DNA and much more. By contrast the Germans and Austrians and their allies, called Clankers, use Steampunk flavored machinery: airplanes and zeppelins, but also great walking land war machines.

The novel is told through the point of view of two teens. Aleksandar is the son of the murdered Serbian Prince Franz Ferdinand and his lower-class wife, and as such is not eligible for the throne, but is still a threat to the powers that be. As the novel opens he is spirited away by a pair of loyal retainers, who fear that the people who arranged for Alek’s parents to be killed will be coming for him. They take a smallish “Walker” and head for Switzerland, fleeing the German army that should be on their side. Meanwhile Deryn Sharp, a girl who has grown up loving to fly the living balloons based on jellyfish genetics, has disguised herself as a boy and joined the Air Service. She ends up a midshipman on the whale-based Leviathan, which is ferrying a valuable but mysterious cargo from England to Turkey, just as war is breaking out.

As we might expect their paths cross … And, in reality, nothing is resolved in this book, no mysteries even unveiled. That will wait for subsequent books, which this reader anticpates eagerly.

The novel is in many ways a familiar YA construction: a hidden Prince, a disguised girl, both people who need to grow up and are being forced to do so in a dangerous situation. The book delights in part because both protagonists are nicely depicted and fun to follow and root for. It also delights in the depiction of the rival, unusual, technologies of the Darwinists and the Clankers. Westerfeld is very good with plausible invented words, and with plausible (to a sufficient degree, at least) inventions, particularly his biological inventions. (The Clanker tech, after all, though different to ours, is still by and large familiar.) There is plenty of exciting action as well. And an intriguing mystery – with the hint that the War may play out a bit differently than in our world – which hold the interest in this book and make subsequent books much to be looked forward to.

Leviathan

by Scott Westerfeld

Simon Pulse

$19.99 | hc | 440 pages

ISBN: 978-1-4169-7173-3

October 2009

A review by Rich Horton

Scott Westerfeld’s Leviathan is a thoroughly delightful Young Adult novel, the first in a series that is based on World War I, but in an alternate history. In this history Charles Darwin discovered the genetic basis for evolution, and how to manipulate it, and as a result the United Kingdom and its allies have a society based on biotechnology, such as the title airship, a huge beast (or colony of organisms) based on whale DNA and much more. By contrast the Germans and Austrians and their allies, called Clankers, use Steampunk flavored machinery: airplanes and zeppelins, but also great walking land war machines.

The novel is told through the point of view of two teens. Aleksandar is the son of the murdered Serbian Prince Franz Ferdinand and his lower-class wife, and as such is not eligible for the throne, but is still a threat to the powers that be. As the novel opens he is spirited away by a pair of loyal retainers, who fear that the people who arranged for Alek’s parents to be killed will be coming for him. They take a smallish “Walker” and head for Switzerland, fleeing the German army that should be on their side. Meanwhile Deryn Sharp, a girl who has grown up loving to fly the living balloons based on jellyfish genetics, has disguised herself as a boy and joined the Air Service. She ends up a midshipman on the whale-based Leviathan, which is ferrying a valuable but mysterious cargo from England to Turkey, just as war is breaking out.

As we might expect their paths cross … And, in reality, nothing is resolved in this book, no mysteries even unveiled. That will wait for subsequent books, which this reader anticpates eagerly.

The novel is in many ways a familiar YA construction: a hidden Prince, a disguised girl, both people who need to grow up and are being forced to do so in a dangerous situation. The book delights in part because both protagonists are nicely depicted and fun to follow and root for. It also delights in the depiction of the rival, unusual, technologies of the Darwinists and the Clankers. Westerfeld is very good with plausible invented words, and with plausible (to a sufficient degree, at least) inventions, particularly his biological inventions. (The Clanker tech, after all, though different to ours, is still by and large familiar.) There is plenty of exciting action as well. And an intriguing mystery – with the hint that the War may play out a bit differently than in our world – which hold the interest in this book and make subsequent books much to be looked forward to.

Review: The Sky So Big and Black, by John Barnes

The Sky So Big and Black, by John Barnes

a review by Rich Horton

This is John Barnes' new novel. It's set in the same future history as his novels Orbital Resonance, Kaleidoscope Century, and Candle. Like Orbital Resonance, it's nominally YA, and very Heinleinian, and very much "to please adults". It's something of a sequel to Orbital Resonance -- I don't remember that book that well, but I'm pretty sure the main character of the new book is a relative of the main character of the older book -- I think a niece. It's also heavily related to Candle, far as I can tell, in that a main plot element is the takeover of Earth by the "One True" meme -- something I deduce happened in Candle, though I'm not quite sure. (I haven't read Candle.) (I say "Future History" but it's really an odd variant -- a sort of Future Alternate History, in that it's set in a future that branches from a near past (at time of writing) history that never happened.)

I just wanted basically to say that I loved this book. As I mention, it's very much in the Heinlein Juvenile mode. There are passages that seem pure quill Heinlein. Here's the protagonist's father and her talking about education in the 20th Century:

"In fact what [20th C. students] got was either a specialty in some academic subject, like math or literature, or certification in some useful trade, like engineering or lying."

"They didn't have certification in lying!"

"Ha! The first place my grandpa taught was a program in something called "communications". Look up the curriculum sometime and tell me that's not a degree in lying!"

And there's plenty more in that vein, about personal responsibility and politics and human relationships.

But more than all that, it's just a good novel. Very well structured -- it's presented as a psychologist listening to a series of interviews he did with Teri-Mel Murray, a young woman on Mars who was working with her father as an "ecospector". It's clear from the start that something terrible happened, and indeed that the psychologist was forced to erase Teri-Mel's memory. It's also clear that he likes her a lot, and is really torn up by what has happened, and worried that he may have to treat her again, for some mysterious reason that takes a long time to become clear.

The interviews tell of Teri and her father travelling across the lightly terraformed planet to a "Gather" of the "rounditachis", people who live more or less in the open on Mars, working to help advance the terraforming. Teri is hoping that she will be certified a "Full Adult" at the Gather, and be free to marry her boyfriend. Her father wants her to go back to school for one more year, because he's not convinced that ecospecting will remain a good living. As they travel, they plan to make one more attempt at a big "scorehole". And Teri is starting to worry about her boyfriend.

All the above is cute stuff, and interleaved with neat SFnal details about the terraforming of Mars. In the background lurk details about the future history up to this point, especially the takeover of ecologically ravaged Earth by a "meme" called "One True", or "Resuna", which more or less has turned Earth's population into a hive mind. Also we learn bits and pieces about the psychologist's feelings, which give us hints about the disaster which has clearly occurred.

So it's a scary book, as we learn to like Teri more and more, while we just know that she's going to get hurt real real bad. And when the crisis comes, it's exciting, and terribly sad, and even scarier than I had first expected.

The resolution is moving, real, and, well, open. Barnes' future is on the one hand full of hope, and of cool SFnal stuff, and on the other hand it is very damned scary, and full of something purely evil, but not EVULL, somehow.

It's a darn good novel, and though it is written about a "young adult" (Teri is about 15), and though it is accessible and readable and appropriate (in my judgement) for teens to read, it is also very effective for adults.

a review by Rich Horton

This is John Barnes' new novel. It's set in the same future history as his novels Orbital Resonance, Kaleidoscope Century, and Candle. Like Orbital Resonance, it's nominally YA, and very Heinleinian, and very much "to please adults". It's something of a sequel to Orbital Resonance -- I don't remember that book that well, but I'm pretty sure the main character of the new book is a relative of the main character of the older book -- I think a niece. It's also heavily related to Candle, far as I can tell, in that a main plot element is the takeover of Earth by the "One True" meme -- something I deduce happened in Candle, though I'm not quite sure. (I haven't read Candle.) (I say "Future History" but it's really an odd variant -- a sort of Future Alternate History, in that it's set in a future that branches from a near past (at time of writing) history that never happened.)

I just wanted basically to say that I loved this book. As I mention, it's very much in the Heinlein Juvenile mode. There are passages that seem pure quill Heinlein. Here's the protagonist's father and her talking about education in the 20th Century:

"In fact what [20th C. students] got was either a specialty in some academic subject, like math or literature, or certification in some useful trade, like engineering or lying."

"They didn't have certification in lying!"

"Ha! The first place my grandpa taught was a program in something called "communications". Look up the curriculum sometime and tell me that's not a degree in lying!"

And there's plenty more in that vein, about personal responsibility and politics and human relationships.

But more than all that, it's just a good novel. Very well structured -- it's presented as a psychologist listening to a series of interviews he did with Teri-Mel Murray, a young woman on Mars who was working with her father as an "ecospector". It's clear from the start that something terrible happened, and indeed that the psychologist was forced to erase Teri-Mel's memory. It's also clear that he likes her a lot, and is really torn up by what has happened, and worried that he may have to treat her again, for some mysterious reason that takes a long time to become clear.

The interviews tell of Teri and her father travelling across the lightly terraformed planet to a "Gather" of the "rounditachis", people who live more or less in the open on Mars, working to help advance the terraforming. Teri is hoping that she will be certified a "Full Adult" at the Gather, and be free to marry her boyfriend. Her father wants her to go back to school for one more year, because he's not convinced that ecospecting will remain a good living. As they travel, they plan to make one more attempt at a big "scorehole". And Teri is starting to worry about her boyfriend.

All the above is cute stuff, and interleaved with neat SFnal details about the terraforming of Mars. In the background lurk details about the future history up to this point, especially the takeover of ecologically ravaged Earth by a "meme" called "One True", or "Resuna", which more or less has turned Earth's population into a hive mind. Also we learn bits and pieces about the psychologist's feelings, which give us hints about the disaster which has clearly occurred.

So it's a scary book, as we learn to like Teri more and more, while we just know that she's going to get hurt real real bad. And when the crisis comes, it's exciting, and terribly sad, and even scarier than I had first expected.

The resolution is moving, real, and, well, open. Barnes' future is on the one hand full of hope, and of cool SFnal stuff, and on the other hand it is very damned scary, and full of something purely evil, but not EVULL, somehow.

It's a darn good novel, and though it is written about a "young adult" (Teri is about 15), and though it is accessible and readable and appropriate (in my judgement) for teens to read, it is also very effective for adults.

Friday, May 1, 2020

Birthday Review: Naomi Novik's first three Temeraire books, plus some short fiction

Naomi Novik was born on the last day of April, so in honor of her birthday, here are some reviews I have done of her (excellent) work, the first a review of the first three Temeraire novels from Black Gate, and then a few reviews of short fiction for Locus.

His Majesty's Dragon/Throne of Jade/Black Powder War

by Naomi Novik. Del Rey, $7.50 each (384/432/400p)

ISBNS: 0345481283 / 0345481291 / 0345481305

March/April/May 2006.

A Review by Rich Horton (Black Gate, Spring 2007)

These three books are the first of a potentially open-ended series [it did, of course, eventually come to completion -- the first 8 covers are shown here, the ninth book, League of Dragons, came out in 2016, and there is also a story collection], set during the Napoleonic Wars in an alternate fantastical past: almost exactly like our history but with dragons. The obvious comparison is with Patrick O'Brian, and it is a high compliment indeed to say that the books are not entirely unworthy of such company as O'Brian's Aubrey/Maturin novels of the British Navy during the Napoleonic Wars (which some consider the best historical novel series ever.) I found Novik's books extremely enjoyable reading, and I look forward to many further volumes. Del Rey's interesting publishing strategy, issuing three books in very quick succession, has evidently garnered Novik and the books well-deserved sales and public attention.

It should be noted that the novels are indeed true series novels: each concluding its sub-story satisfyingly enough, but also advancing an overall arc. The series opens with Captain Will Laurence of the English Navy capturing a French ship, on which there is a dragon egg. When dragons hatch they are "harnessed" by a person who will be their constant companion: usually an aviator, but no such candidate being available the man chosen is Laurence himself. This means the end of his promising Naval career, and an unconventional life as one of the rather raffish Aerial Corps, but the friendship of the dragon, a very unusual specimen he names Temeraire, proves to be ample compensation. His Majesty's Dragon (titled Temeraire in the UK) details the training of Laurence and Temeraire, complete with some internal conflicts and adjustments, leading to their first battles and the revelation of Temeraire's particularly special war-fighting power, unique to his variety of extremely rare dragon. This variety, it transpires, is the Chinese Celestial, usually reserved to be companions of the Chinese Imperial Family.

In Throne of Jade the Chinese protest the British capture of Temeraire (who had been intended as a gift for Napoleon), and the spineless Foreign Office sends Laurence, Temeraire, and crew to China, hoping to negotiate better trading rights in exchange for returning this valuable dragon. But while Temeraire enjoys China, in particular the special privileges -- or, perhaps, ordinary rights that all intelligent creatures ought to enjoy -- given dragons there, he refuses to be separated from Laurence. Also, it turns out there is some political turmoil in China -- the resolution of which leads also to an accommodation that allows Laurence and Temeraire to remain together.

Black Powder War is the story of their desperate land journey first to Istanbul, to collect three more dragon eggs the British have bought from the Turks, then through war-torn Europe, where they learn that Napoleon has a new Celestial -- one who has cause to hate Laurence, Temeraire, and by extension England.

The first book is nearly an unalloyed delight (save the slightly unprepared-for nature of the end), the second is enjoyable but a step down, perhaps a bit too slow; and the third ranks pretty much with the second, though the ending is surprising and quite moving. The series as a whole promises to continue to be very fun reading, with a nicely set up tension between the necessity of defeating Napoleon and the cause of "Dragon's Rights", which Temeraire has at last persuaded Laurence is both morally and practically essential. Both lead characters are engaging and well-depicted, the prose is nicely handled with a sound period flavor, the fantastical elements are not terribly plausible (nor necessarily consistent) but they (draconic characteristics and types, basically) are nicely imagined. Recommended.

Review of Fast Ships, Black Sails (Locus, December 2008)

One coup the VanderMeers managed was to land a novelette from Naomi Novik. (To my knowledge she has only published two other short stories, both quite short, at her website.) “Araminta; or, The Wreck of the Amphidrake” is one of the best pieces in this book. It’s not a Temeraire story -- it is a gender-bending tale of a rather tomboyish girl of a noble family sent by sea to marry the young man her parents have chosen. When pirates attack her ship, she resorts to a special magical protection she has been given … the results are entertaining and in the end Araminta gets the chance to make her own choices for her future, choices that not too surprisingly involve adventure and piracy.

Review of Warriors (Locus, May 2010)

Naomi Novik shows up with her first straight SF story (that I know of), “Seven Years From Home”, about a diplomat sent to an alien planet, charged with mediating somehow between two human variant groups, one of which has colonized one continent by altering themselves to blend in with the established ecology, the other of which, latecomers, are bent on terraforming the planet, and having conquered their continent are now proceeding to the other. The diplomat, not surprisingly, goes native (as it were), only to become complicit in what she can’t help seeing a terrible crime. The story has some intriguing elements, but doesn’t really convince. But it’s nice to see Novik continue to extend her range – she is serving notice that she won’t be tied to Temeraire for her whole career.

Review of Naked City (Locus, August 2011)

More lighthearted are stories like Naomi Novik’s “Priced to Sell”, about various problems a real estate agent deals with in selling to the magical community – slight, to be sure, but fun.

Locus, January 2017

One of my favorite stories in The Starlit Wood is Naomi Novik’s “Spinning Silver”. As one might guess, Rumpelstiltskin in the base story. The conceit is that instead of spinning straw into gold, a moneylender might be seen as spinning silver (a small amount of money) into a larger amount (gold). The narrator is the daughter of a poor village moneylender, too kindly to make a living. The daughter, however, has learned to harden her heart to her father’s clients’ troubles – which often enough are invented anyway – and under her stewardship the family has prospered – but at what cost? Especially when a fairy creature called the Staryk learns of her abilities, and insists that she spin his silver into gold. The mechanism she uses is clever, and the expected complications ensue, especially when the local Duke is involved. Novik very effectively layers the story with meaning – most notably the status of the moneylenders, who are (of course) Jewish – which points as well to a perhaps sometimes missed element of Rumpelstiltskin’s traditional portrayal. As with many of the stories in this book (and indeed in most contemporary fairy tale versions) the agency or lack thereof of the female characters is also central, and quite matter of factly and honestly treated.

His Majesty's Dragon/Throne of Jade/Black Powder War

by Naomi Novik. Del Rey, $7.50 each (384/432/400p)

ISBNS: 0345481283 / 0345481291 / 0345481305

March/April/May 2006.

A Review by Rich Horton (Black Gate, Spring 2007)

These three books are the first of a potentially open-ended series [it did, of course, eventually come to completion -- the first 8 covers are shown here, the ninth book, League of Dragons, came out in 2016, and there is also a story collection], set during the Napoleonic Wars in an alternate fantastical past: almost exactly like our history but with dragons. The obvious comparison is with Patrick O'Brian, and it is a high compliment indeed to say that the books are not entirely unworthy of such company as O'Brian's Aubrey/Maturin novels of the British Navy during the Napoleonic Wars (which some consider the best historical novel series ever.) I found Novik's books extremely enjoyable reading, and I look forward to many further volumes. Del Rey's interesting publishing strategy, issuing three books in very quick succession, has evidently garnered Novik and the books well-deserved sales and public attention.

It should be noted that the novels are indeed true series novels: each concluding its sub-story satisfyingly enough, but also advancing an overall arc. The series opens with Captain Will Laurence of the English Navy capturing a French ship, on which there is a dragon egg. When dragons hatch they are "harnessed" by a person who will be their constant companion: usually an aviator, but no such candidate being available the man chosen is Laurence himself. This means the end of his promising Naval career, and an unconventional life as one of the rather raffish Aerial Corps, but the friendship of the dragon, a very unusual specimen he names Temeraire, proves to be ample compensation. His Majesty's Dragon (titled Temeraire in the UK) details the training of Laurence and Temeraire, complete with some internal conflicts and adjustments, leading to their first battles and the revelation of Temeraire's particularly special war-fighting power, unique to his variety of extremely rare dragon. This variety, it transpires, is the Chinese Celestial, usually reserved to be companions of the Chinese Imperial Family.

In Throne of Jade the Chinese protest the British capture of Temeraire (who had been intended as a gift for Napoleon), and the spineless Foreign Office sends Laurence, Temeraire, and crew to China, hoping to negotiate better trading rights in exchange for returning this valuable dragon. But while Temeraire enjoys China, in particular the special privileges -- or, perhaps, ordinary rights that all intelligent creatures ought to enjoy -- given dragons there, he refuses to be separated from Laurence. Also, it turns out there is some political turmoil in China -- the resolution of which leads also to an accommodation that allows Laurence and Temeraire to remain together.

Black Powder War is the story of their desperate land journey first to Istanbul, to collect three more dragon eggs the British have bought from the Turks, then through war-torn Europe, where they learn that Napoleon has a new Celestial -- one who has cause to hate Laurence, Temeraire, and by extension England.

The first book is nearly an unalloyed delight (save the slightly unprepared-for nature of the end), the second is enjoyable but a step down, perhaps a bit too slow; and the third ranks pretty much with the second, though the ending is surprising and quite moving. The series as a whole promises to continue to be very fun reading, with a nicely set up tension between the necessity of defeating Napoleon and the cause of "Dragon's Rights", which Temeraire has at last persuaded Laurence is both morally and practically essential. Both lead characters are engaging and well-depicted, the prose is nicely handled with a sound period flavor, the fantastical elements are not terribly plausible (nor necessarily consistent) but they (draconic characteristics and types, basically) are nicely imagined. Recommended.

Review of Fast Ships, Black Sails (Locus, December 2008)

One coup the VanderMeers managed was to land a novelette from Naomi Novik. (To my knowledge she has only published two other short stories, both quite short, at her website.) “Araminta; or, The Wreck of the Amphidrake” is one of the best pieces in this book. It’s not a Temeraire story -- it is a gender-bending tale of a rather tomboyish girl of a noble family sent by sea to marry the young man her parents have chosen. When pirates attack her ship, she resorts to a special magical protection she has been given … the results are entertaining and in the end Araminta gets the chance to make her own choices for her future, choices that not too surprisingly involve adventure and piracy.

Review of Warriors (Locus, May 2010)

Naomi Novik shows up with her first straight SF story (that I know of), “Seven Years From Home”, about a diplomat sent to an alien planet, charged with mediating somehow between two human variant groups, one of which has colonized one continent by altering themselves to blend in with the established ecology, the other of which, latecomers, are bent on terraforming the planet, and having conquered their continent are now proceeding to the other. The diplomat, not surprisingly, goes native (as it were), only to become complicit in what she can’t help seeing a terrible crime. The story has some intriguing elements, but doesn’t really convince. But it’s nice to see Novik continue to extend her range – she is serving notice that she won’t be tied to Temeraire for her whole career.

Review of Naked City (Locus, August 2011)

More lighthearted are stories like Naomi Novik’s “Priced to Sell”, about various problems a real estate agent deals with in selling to the magical community – slight, to be sure, but fun.

Locus, January 2017

One of my favorite stories in The Starlit Wood is Naomi Novik’s “Spinning Silver”. As one might guess, Rumpelstiltskin in the base story. The conceit is that instead of spinning straw into gold, a moneylender might be seen as spinning silver (a small amount of money) into a larger amount (gold). The narrator is the daughter of a poor village moneylender, too kindly to make a living. The daughter, however, has learned to harden her heart to her father’s clients’ troubles – which often enough are invented anyway – and under her stewardship the family has prospered – but at what cost? Especially when a fairy creature called the Staryk learns of her abilities, and insists that she spin his silver into gold. The mechanism she uses is clever, and the expected complications ensue, especially when the local Duke is involved. Novik very effectively layers the story with meaning – most notably the status of the moneylenders, who are (of course) Jewish – which points as well to a perhaps sometimes missed element of Rumpelstiltskin’s traditional portrayal. As with many of the stories in this book (and indeed in most contemporary fairy tale versions) the agency or lack thereof of the female characters is also central, and quite matter of factly and honestly treated.

Friday, April 24, 2020

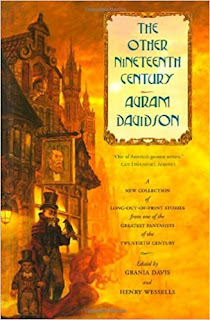

Birthday Review: The Other Nineteenth Century, by Avram Davidson

This is slightly belated -- Avram Davidson would have turned 97 yesterday. Gosh, he was a wonderful writer! I've previously covered a couple of his Ace Doubles, and I've posted a survey of his novels, and a review of The Avram Davidson Treasury, so here's a very short bit I wrote for my blog some long while ago about another posthumous collection, The Other Nineteenth Century.

[On reflection, I've regretted posting that rather casually tossed off old blog entry, and I've produced a more thorough review here:

Review of The Other Nineteenth Century.]

[On reflection, I've regretted posting that rather casually tossed off old blog entry, and I've produced a more thorough review here:

Review of The Other Nineteenth Century.]

Tuesday, April 14, 2020

Birthday Review: Stories of Bruce Sterling

I can't believe I haven't done one of these birthday review collections for Bruce Sterling yet. So here we go! This is a collection of my reviews of his short work from my Locus column. Happy Birthday -- Bruce Sterling turns 66 today.

Locus, September 2002

Bruce Sterling's short story "In Paradise" (F&SF, September) is a fine romp, extrapolating a bit from our current "Homeland Security" measure. Felix is a plumber who falls for a beautiful Iranian woman he sees at the airport, and with the help of a high-tech Finnish cellphone he manages to seduce her. Their whirlwind romance is interrupted when it turns out to have political repercussions. Where then is freedom or paradise in a high-tech, security obsessed, world? Sterling has an answer. A fun story, and oddly romantic (as Sterling often is – perhaps in contrast to his reputation), though it lacks the extrapolative snap of Sterling at his most characteristic.

Locus, January 2003

Another fun piece from the January Asimov's is Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling's "Junk DNA", a story fully as frenetic as we expect from that duo. Janna Gutierrez is a half-Vietnamese, half-Latino woman sometime in the next few decades, who more or less randomly enters into business with a Russian immigrant who wants to market a pet based on human junk DNA, particularly the pet owner's own DNA. Before long they are dealing with a big corporation's takeover attempt. How much sense this all makes is questionable, but the story is a fun romp.

Locus, January 2005

Bruce Sterling's "The Blemmye's Stratagem" highlights the January F&SF. Hildegart is a nun who runs a far-flung commercial venture in the Middle East towards the end of the Crusades. Sinan is an Assassin, and at one time Hildegart was one of Sinan's wives. They both work for a mysterious entity called the Silent Master. As the story opens, they are called to their Master once again – they assume simply to receive instructions and to be given another dose of life extension elixir, but in fact something rather more important is going on. The story is by turns cynical, cynically romantic, scary, moving, and fascinating. An award contender, I would think. And at Sci Fiction in December we find Bruce Sterling's "Luciferase", a funny story about a male firefly looking for love, and finding it in a rather dangerous place.

Locus, September 2005

I also liked Bruce Sterling's "The Denial" (F&SF, September), about a husband and wife in an Eastern European town some centuries ago, whose lives are changed by a terrible flood. Indeed, the wife seems to have died in the flood – but to have somehow come back to life. The husband's attempts to deal with his changed wife lead him to an unexpected revelation.

Locus, January 2007

The cover story for the January F&SF is a new novella by Bruce Sterling, certainly a welcome sight. That said, while “Kiosk” is an interesting story, it seems a bit unfocussed – it doesn’t quite work. It concerns an aging Eastern European war veteran, sometime a few decades in the future, who operates a small shopping kiosk which becomes the center of a revolution of sorts when he obtains a black-market “fabrikator”, which can make a duplicate of most anything out of nanotubes. It seems the authorities have all read “Business as Usual, During Alterations” and A for Anything, so they are concerned about such a machine’s impact on the economy … but in the end, information wants to be free. The ideas here are certainly worth exploring – but the story doesn’t really grapple with them – more interesting, really, are the colorful characters – but they don’t really have a story of their own.

Locus, August 2007

The online magazines have not been silent either. I finally caught up with Subterranean’s Spring issue. Bruce Sterling’s “A Plain Tale from Our Hills” is a subtle sketch of a post-catastrophe future, told in Kiplingesque fashion about a wife’s brave effort to keep her husband in the face of an exotic woman’s affair with him. It is of course the stark details of this deprived future, quietly slipped in, that make the story powerful.

Locus, November 2007

Eclipse One is yet another strong original anthology from Locus Reviews Editor Jonathan Strahan. Highlights include a truly odd story from Bruce Sterling, “The Lustration”, about an isolated planet on which the inhabitants have built and maintain an entirely wooden, world-spanning, computer. The protagonist realizes that something strange is happening with the computer, and ends up in a society which guards a terrible secret. The story is in one way almost too strange, but in the end successfully ponders a central SF question

Locus, February 2009

Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling have lots of fun with the end of the universe in “Colliding Branes” (Asimov's, February). Bloggers Rabbiteen Chandra and Angelo Rasmussen have learned that for either mystical or physical reasons the structure of the universe is collapsing. So they head for Area 51 (sort of ) to witness the end as best they can – and to have some “pre-apocalypse sex”. Post, too, as it, rather sweetly, turns out.

Locus, June 2009

The March-April Interzone features a Bruce Sterling story – not that he was ever gone, but Sterling seems “back” this year, with a new novel and now “Black Swan”, gritty and savvy, with a journalist lured across multiple timelines, chasing wild tech not to mention a revolutionary version of Nicolas Sarkozy.

Locus, September 2009

And Bruce Sterling offers a clever fantasy about an Italian auto executive encountering the devil – or something like him – in “Esoteric City” (F&SF, August-September). The story is fun, original – certainly worth reading, but at some level it struck me as insubstantial.

Review of Subterranean 2: Tales of Dark Fantasy (Locus, May 2011)

Another story I particularly enjoyed comes from Bruce Sterling. “The Parthenopean Scalpel” concerns an assassin who has to flee the Papal States after the too clumsy success of one of his assignments. In exile he falls in love – but a certain Transylvanian intervenes. The story rides on the well-maintained voice of the main character, and the backstory of Europe in the turbulent middle of the 19th Century.

Locus, June 2012

Nick Mamatas and Masumi Washington offer The Future is Japanese, which collects a number of SF stories about, in some sense, a Japaneses future, as well as a few stories by Japanese SF writers. ... From English-language writers, I liked Bruce Sterling's “Goddess of Mercy”, a characteristically smart and cynical story set on a Japanese island ruled by a Pirate Queen where a woman comes to negotiate for the freedom of a political agitator;

Locus, January 2014

A Bruce Sterling story showed up in Dissident Blog, "N'existe Pas", not really SF but certainly involved with SFnal ideas, so that it seems worth bringing to Locus reader's attentions. It's a somewhat comic story about privacy and the lack thereof, set as a conversation in a Paris cafe between a paparazzo and his brother, a spy (a double agent, indeed), as they await the rumored arrival of the Prime Minister and his newest mistress, while discussing the nature of their similar businesses, and of privacy and surveillance in the modern digital age, eventually involving an American spy and a Syrian woman and an actress who was also previously the Prime Minister's mistress ... nothing much really happens but the story is intellectually interesting and quite funny.

Locus, September 2002

Bruce Sterling's short story "In Paradise" (F&SF, September) is a fine romp, extrapolating a bit from our current "Homeland Security" measure. Felix is a plumber who falls for a beautiful Iranian woman he sees at the airport, and with the help of a high-tech Finnish cellphone he manages to seduce her. Their whirlwind romance is interrupted when it turns out to have political repercussions. Where then is freedom or paradise in a high-tech, security obsessed, world? Sterling has an answer. A fun story, and oddly romantic (as Sterling often is – perhaps in contrast to his reputation), though it lacks the extrapolative snap of Sterling at his most characteristic.

Locus, January 2003

Another fun piece from the January Asimov's is Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling's "Junk DNA", a story fully as frenetic as we expect from that duo. Janna Gutierrez is a half-Vietnamese, half-Latino woman sometime in the next few decades, who more or less randomly enters into business with a Russian immigrant who wants to market a pet based on human junk DNA, particularly the pet owner's own DNA. Before long they are dealing with a big corporation's takeover attempt. How much sense this all makes is questionable, but the story is a fun romp.

Locus, January 2005

Bruce Sterling's "The Blemmye's Stratagem" highlights the January F&SF. Hildegart is a nun who runs a far-flung commercial venture in the Middle East towards the end of the Crusades. Sinan is an Assassin, and at one time Hildegart was one of Sinan's wives. They both work for a mysterious entity called the Silent Master. As the story opens, they are called to their Master once again – they assume simply to receive instructions and to be given another dose of life extension elixir, but in fact something rather more important is going on. The story is by turns cynical, cynically romantic, scary, moving, and fascinating. An award contender, I would think. And at Sci Fiction in December we find Bruce Sterling's "Luciferase", a funny story about a male firefly looking for love, and finding it in a rather dangerous place.

Locus, September 2005

I also liked Bruce Sterling's "The Denial" (F&SF, September), about a husband and wife in an Eastern European town some centuries ago, whose lives are changed by a terrible flood. Indeed, the wife seems to have died in the flood – but to have somehow come back to life. The husband's attempts to deal with his changed wife lead him to an unexpected revelation.

Locus, January 2007

The cover story for the January F&SF is a new novella by Bruce Sterling, certainly a welcome sight. That said, while “Kiosk” is an interesting story, it seems a bit unfocussed – it doesn’t quite work. It concerns an aging Eastern European war veteran, sometime a few decades in the future, who operates a small shopping kiosk which becomes the center of a revolution of sorts when he obtains a black-market “fabrikator”, which can make a duplicate of most anything out of nanotubes. It seems the authorities have all read “Business as Usual, During Alterations” and A for Anything, so they are concerned about such a machine’s impact on the economy … but in the end, information wants to be free. The ideas here are certainly worth exploring – but the story doesn’t really grapple with them – more interesting, really, are the colorful characters – but they don’t really have a story of their own.

Locus, August 2007

The online magazines have not been silent either. I finally caught up with Subterranean’s Spring issue. Bruce Sterling’s “A Plain Tale from Our Hills” is a subtle sketch of a post-catastrophe future, told in Kiplingesque fashion about a wife’s brave effort to keep her husband in the face of an exotic woman’s affair with him. It is of course the stark details of this deprived future, quietly slipped in, that make the story powerful.

Locus, November 2007

Eclipse One is yet another strong original anthology from Locus Reviews Editor Jonathan Strahan. Highlights include a truly odd story from Bruce Sterling, “The Lustration”, about an isolated planet on which the inhabitants have built and maintain an entirely wooden, world-spanning, computer. The protagonist realizes that something strange is happening with the computer, and ends up in a society which guards a terrible secret. The story is in one way almost too strange, but in the end successfully ponders a central SF question

Locus, February 2009

Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling have lots of fun with the end of the universe in “Colliding Branes” (Asimov's, February). Bloggers Rabbiteen Chandra and Angelo Rasmussen have learned that for either mystical or physical reasons the structure of the universe is collapsing. So they head for Area 51 (sort of ) to witness the end as best they can – and to have some “pre-apocalypse sex”. Post, too, as it, rather sweetly, turns out.

Locus, June 2009

The March-April Interzone features a Bruce Sterling story – not that he was ever gone, but Sterling seems “back” this year, with a new novel and now “Black Swan”, gritty and savvy, with a journalist lured across multiple timelines, chasing wild tech not to mention a revolutionary version of Nicolas Sarkozy.

Locus, September 2009

And Bruce Sterling offers a clever fantasy about an Italian auto executive encountering the devil – or something like him – in “Esoteric City” (F&SF, August-September). The story is fun, original – certainly worth reading, but at some level it struck me as insubstantial.

Review of Subterranean 2: Tales of Dark Fantasy (Locus, May 2011)

Another story I particularly enjoyed comes from Bruce Sterling. “The Parthenopean Scalpel” concerns an assassin who has to flee the Papal States after the too clumsy success of one of his assignments. In exile he falls in love – but a certain Transylvanian intervenes. The story rides on the well-maintained voice of the main character, and the backstory of Europe in the turbulent middle of the 19th Century.

Locus, June 2012

Nick Mamatas and Masumi Washington offer The Future is Japanese, which collects a number of SF stories about, in some sense, a Japaneses future, as well as a few stories by Japanese SF writers. ... From English-language writers, I liked Bruce Sterling's “Goddess of Mercy”, a characteristically smart and cynical story set on a Japanese island ruled by a Pirate Queen where a woman comes to negotiate for the freedom of a political agitator;

Locus, January 2014

A Bruce Sterling story showed up in Dissident Blog, "N'existe Pas", not really SF but certainly involved with SFnal ideas, so that it seems worth bringing to Locus reader's attentions. It's a somewhat comic story about privacy and the lack thereof, set as a conversation in a Paris cafe between a paparazzo and his brother, a spy (a double agent, indeed), as they await the rumored arrival of the Prime Minister and his newest mistress, while discussing the nature of their similar businesses, and of privacy and surveillance in the modern digital age, eventually involving an American spy and a Syrian woman and an actress who was also previously the Prime Minister's mistress ... nothing much really happens but the story is intellectually interesting and quite funny.

Monday, April 13, 2020

Birthday Review: Stories of Theodore L. Thomas

Theodore L. Thomas (1920-2005) is probably best known in the SF field for his novel with Kate Wilhelm, The Clone (expanded from Thomas' short story reviewed herein.) He was a chemical engineer and patent lawyer, and he is also known for a series of four stories examining SFnal notions from a patent lawyer's view, written as by "Leonard Lockhard", because the first of these stories ("The Professional Look") was written with another SF writer/Patent lawyer, Charles L. Harness, and the pseudonym combines their two middle names. He was born on this date, so following is a look at a few of his short stories, based on reviews I did of the old magazines they appeared in.

Review of Space Science Fiction, September 1952

Finally, Theodore L. Thomas's "The Revisitor" is set in the near future after a test has been developed to determine everyone's capacity and abilities. The story tells of a mysterious person taking the test and proving to be a "Number One" -- i.e. perfect in everything, more or less. He embarks on a project to create life ... The meaning is a bit obscure, signalled only at the end by the title and a reference to a lot of progress in the past 2000 years.

Review of Future #28

Theodore L. Thomas's "Trial Without Combat" (9000 words) is another didactic story in nature. In this case the villain is religion. An agent of the Federal Bureau of Control is stationed on a distant planet, charged with guiding it to civilization in subtle ways. Unfortunately, the bleeding hearts/meddlers/whatever back on Earth have decided that simply assassinating the bad guys won't do. (In the story, this anti-assassination view is presented as a ridiculous stance on the face of it.) So our hero must work more cleverly, especially if he wants to get back to Earth in time for his baby to be born. (This is an enlightened future society, so naturally all the women are pregnant and barefoot in the kitchen ...) What's the problem? An oppressive religion, one in particular that has begun engaging in simony. And what's the "subtle" solution? Get arrested for heresy, and in the trial, convince the religious leaders that they are wrong by arguments so sophisticated any sophomore will be glad to use them! And use your handy-dandy force field plus personal spaceship to fend off trouble. A stupid stupid story, kind of a low rent knockoff of Everett Cole's Philosophical Corps.

Review of Super Science Fiction, August 1957

"Twice-Told Tale", by Theodore L. Thomas, is also silly -- an obsessed scientist has determined that space is curved and that a starship can travel around it in 15 years. Everyone scoffs at him. But he gets funding from the Queen -- no, Madam President -- of Castile -- no, Brazil -- and he takes a spaceship -- no, THREE spaceships ... and of course he is proved right. You really don't want to know -- well, you already do know, I'm sure -- what the spaceships were named. (I also did some math. His ships are stated to travel 4*1028c -- so in 15 years they would go some 60,000 light years. THAT is enough to go around the universe?????)

Review of Fantastic, January 1959

Theodore Thomas’s “The Clone” is a somewhat well-known story, later expanded, with Kate Wilhelm, to a novel of the same title. The title creature is not what we would now think of as a “clone,” but rather a spontaneously generated life form, created in the sewers of a Midwestern city that appears to be Chicago, that feeds on anything it encounters, including people.

It’s pure SF horror (with an obvious ecological theme), and it drives from its open to the necessary dark conclusion, mostly by exposition.

Review of Fantastic, February 1964

The other short story is a short-short from Theodore L. Thomas: “The Soft Woman,” a horror story that I confess I didn’t quite get, about a man who encounters a beautiful woman and takes her to bed — with, to coin a phrase, unfortunate effects. Here Thomas was too subtle for me, I suppose — was this revenge from a briefly mentioned previous lover?

Review of Space Science Fiction, September 1952

Finally, Theodore L. Thomas's "The Revisitor" is set in the near future after a test has been developed to determine everyone's capacity and abilities. The story tells of a mysterious person taking the test and proving to be a "Number One" -- i.e. perfect in everything, more or less. He embarks on a project to create life ... The meaning is a bit obscure, signalled only at the end by the title and a reference to a lot of progress in the past 2000 years.

Review of Future #28

Theodore L. Thomas's "Trial Without Combat" (9000 words) is another didactic story in nature. In this case the villain is religion. An agent of the Federal Bureau of Control is stationed on a distant planet, charged with guiding it to civilization in subtle ways. Unfortunately, the bleeding hearts/meddlers/whatever back on Earth have decided that simply assassinating the bad guys won't do. (In the story, this anti-assassination view is presented as a ridiculous stance on the face of it.) So our hero must work more cleverly, especially if he wants to get back to Earth in time for his baby to be born. (This is an enlightened future society, so naturally all the women are pregnant and barefoot in the kitchen ...) What's the problem? An oppressive religion, one in particular that has begun engaging in simony. And what's the "subtle" solution? Get arrested for heresy, and in the trial, convince the religious leaders that they are wrong by arguments so sophisticated any sophomore will be glad to use them! And use your handy-dandy force field plus personal spaceship to fend off trouble. A stupid stupid story, kind of a low rent knockoff of Everett Cole's Philosophical Corps.

Review of Super Science Fiction, August 1957

"Twice-Told Tale", by Theodore L. Thomas, is also silly -- an obsessed scientist has determined that space is curved and that a starship can travel around it in 15 years. Everyone scoffs at him. But he gets funding from the Queen -- no, Madam President -- of Castile -- no, Brazil -- and he takes a spaceship -- no, THREE spaceships ... and of course he is proved right. You really don't want to know -- well, you already do know, I'm sure -- what the spaceships were named. (I also did some math. His ships are stated to travel 4*1028c -- so in 15 years they would go some 60,000 light years. THAT is enough to go around the universe?????)

Review of Fantastic, January 1959

Theodore Thomas’s “The Clone” is a somewhat well-known story, later expanded, with Kate Wilhelm, to a novel of the same title. The title creature is not what we would now think of as a “clone,” but rather a spontaneously generated life form, created in the sewers of a Midwestern city that appears to be Chicago, that feeds on anything it encounters, including people.

It’s pure SF horror (with an obvious ecological theme), and it drives from its open to the necessary dark conclusion, mostly by exposition.

Review of Fantastic, February 1964

The other short story is a short-short from Theodore L. Thomas: “The Soft Woman,” a horror story that I confess I didn’t quite get, about a man who encounters a beautiful woman and takes her to bed — with, to coin a phrase, unfortunate effects. Here Thomas was too subtle for me, I suppose — was this revenge from a briefly mentioned previous lover?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)