Convention Report: World Fantasy 2022

by Rich Horton

At last I made it to another World Fantasy Convention. The last one I attended was in San Antonio in 2017, and I loved that. World Fantasy is a somewhat more writer-oriented, more professional-oriented, convention than, say, Worldcon. Both orientations are wonderful, but the World Fantasy slant is something I do love. Anyway, for one reason and another I missed 2018 and 2019. And of course 2020 was virtual-only -- I did do a panel for that con, but virtual just isn't the same. I had tickets and a hotel and all for 2021 in Montreal -- and I had to cancel for COVID-related reasons. So finally this year I made it back! This time was in New Orleans -- next year will be in Kansas City, practically home for me! -- I'll be there for sure, unless some other disaster intervenes.

Mary Ann made the trip with me. We drove down on Thursday, stopping in Memphis for lunch at Dyer's, a legendary hamburger joint (the grease they use is supposedly over 100 years old) -- I have to say it was fine -- but not awesome. Then we continued to Laurel, MS, where the home renovation show Hometown is set. We stayed the night, and visited their downtown the next morning. The shops run by the stars of Hometown were cute enough, but rather ridiculously overpriced. Then we headed into New Orleans, getting to the hotel at 12:30 or so.(Mary Ann made a musical record of our trip -- I'll post it, with links to the songs, at the end of this post.)

I have to say it was a delight walking through the hotel on the way to the elevators up to our room, with the porter taking our bags, and old friends calling my name -- I stopped to say hi several times, no doubt to the frustration of Mary Ann and the porter. I got to meet several of Fran Wilde's writing students, for one thing. It is just so nice to be at live conventions again (this wasn't my first -- I was at Boskone in February and at Worldcon, but still!)

The hotel is kind of nice, particularly the interior architecture -- some 27 floors, in a sort of wedge shape, with dizzying empty space up to the top. That said, as with pretty much every hotel we've stayed in recently, the furniture is terribly uncomfortable.

We had a quick lunch in the hotel restaurant -- which was just fine if of course overpriced -- and Ron Drummond came coursing by and recognized me by my beard. We had a good talk and agreed to meet later. And, indeed, we went to dinner that night, at Reginelli's Pizzeria. Ron, of course, discussed the limited edition of John Crowley's great novel Little, Big, which Ron (along with John Berry) has been working on for some 15 years, and it is finally coming out. (My copy will arrive in a few weeks, I'm sure.) Ron had the first sample of the book to show off -- it's a beautiful creature indeed.

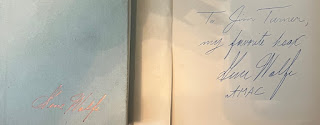

Before dinner I made a quick dash through the dealers' room, and ran into Arin Komins and Rich Warren, and had the first of several conversations with them. (I also saw them, and had dinner with them, at Windycon the following week.) Then I was looking in at a panel but instead ran into Jim Cambias and Gordon van Gelder, and soon we were joined by Jo Walton, and we spent the next hour talking about -- about cozy catastrophes and many other things. And I spent the evening after dinner at the bar, meeting people and talking -- that was my MO for the whole convention. Panels are great, sure, and readings, and the Dealers' Room -- but the best part of a convention is hanging around the bar and having conversations.

After dinner there was the mass signing. I had signed up for a spot this time, but once again I forgot to bring my books. I'll get the hang of it someday! I was sitting next to Ron, and took the opportunity to look through Little, Big. Bruce McAllister was there too, and I finally not to meet him though we didn't get to talk much. I signed one or two of my books that other people had brought, but mostly wandered through the room trying to meet other authors I hadn't met yet, and to catch up with some of my long time friends. Among the many people I ran into were Sharon Shinn, Peter Halasz, Nina Kiriki Hoffman, Claire Cooney and Carlos Hernandez, Ellen Klages, Kathleen Jennings, Fran Wilde (who, happily, I bumped into numerous times over the weekend), Laura Anne Gilman, Emily C. Skaftun, Marie Brennan, and E. C. Ambrose. They had a nice spread too -- both Friday and Saturday night! Of course, being in New Orleans helps a lot! Then to the bar, and more conversations.

Saturday I grabbed breakfast at a place called District, apparently a chain of some sort, in close walking distance from the hotel. It was OK, not great. My only panel was at 3, though there was one at 2 I also wanted to see. So I spent a good while in the Dealers' Room. It was fairly small, but the sellers who were there had interesting stuff. I saw Sally Kobee of course, and Jacob Weisman, Patrick Swenson, and James Van Pelt, and Allen Kaster and his daughter. And I also met a dealer named Donna Rankin, who had some interesting stuff but probably a lot more at her place in South Carolina. As we make it to South Carolina every so often (though it's been a while), there's a chance I'll be able to visit her store some time. Susan Forest was there too, helping to sell her daughter's novel. Naturally I bought some books. The convention also gave us quite a nice book bag (books included).

The first panel I went to was on the place of essays in science fiction. The panelists were Nisi Shawl, Farah Mendlesohn, Teresa Nielsen Hayden, Eileen Gunn, and Farah's husband Edward James. They discussed the form of the essay, several famous and influential essays, etc. etc. -- all interesting and worthwhile stuff (and as I've been known to write the occasional essay, motivating to me!) This was my first chance to meet Farah and Edward in person -- we've been FB friends for a long time. Edward and I had a nice discussion, particularly on Tolkien's "On Fairy Stories", which I read for the first time (!) a few months ago, and was very impressed by.

The only panel I was actually on was on the Author/Editor Relationship. I moderated, as Jeffrey Ford and Ellen Datlow talked about their editing process; and Donna Glee Williams and Jo Fletcher talked about theirs. I think it went very well. Lots of good talk about the mechanics, the effects of COVID (and technology in general), levels of editing (structural, prose, line, copy), as well as issues with things like what happens when an editor leaves a company (sometimes not by their choice) and the author has to work with a new person. And some gossip (no names though.)

For dinner this time we decided I'd pick up takeout from a place called Daisy Mae's Southern Fried Chicken. Again, it was good, though there was almost a fight between two people waiting for takeout. And I ran into Jo Fletcher again, eating with a couple of her friends, and Sharon Shinn with Ginjer Buchanan. We got to chat for a bit while I waited for my food. Again, good stuff, probably would have been better eaten in the restaurant.

There was an art exhibit/auction that night. The art show, alas, was a bit thin this year, though there were some excellent artists, including one of my favorites (a favorite writer too), Kathleen Jennings. A good spread as well, again. At the bar afterward we were treated to the Alabama/LSU football game, which was extremely exciting, and naturally the locals were thrilled when LSU pulled off a miraculous finish to win the game. The final World Series game was on, too -- a very good result for Allen Kaster, who is from Houston. And, of course, long conversations with lots of people -- I met Marc Laidlaw in person at last, and talked to Scott Andrews, Jake Wyckoff, Brandon McNulty, Tod McCoy, Christopher Cevasco and others. (And disappointment as I learned that, all too typically, the hotel bar couldn't make an Aviation, though at least the bartender knew what I was talking about!)

Sunday was a light day at the convention, especially as we weren't going to the award banquet. I sat in on the WFC Board meeting for a bit -- I find this stuff quite interesting, perhaps surprisingly. Visitors, of course, were kicked out when they got to sensitive subjects.

Mary Ann and I had decided to use Sunday afternoon to visit the French Quarter. We took the streetcar down there -- it's very easy and convenient. We were going to get lunch and I was determined to get a muffeletta, which is one of my favorite sandwiches. I wanted an authentic muffuletta from New Orleans -- which I got at Frank's, which advertised the "original muffuletta". Alas, it might be the original, and it was fine, but you can get one just as good at, for example, C. J. Mugg's in my town of Webster Groves. We should have eaten at the French Market Restaurant instead! We also, of course, went to Cafe du Monde to try beignets, and, hey, they were actually very good. (The line was long but went quickly.)I had more conversations that night, of course -- finally running into Sarah Pinsker, and meeting A. T. Greenblatt -- we had a real good talk, talking engineering as much as writing. There was also an interesting writer from, I think, Pakistan, an historian who is working on an epic novel based on the history of Afghanistan. Alas, between the noise at the bar and my aging ears (which have a hard time with background noise these days) I didn't catch his name!Monday was of course farewells, and another dealers' room sweep. I'll go ahead and namecheck everyone else I remember talking to, though I'm sure I've forgotten some:

Christopher Rowe, Gwenda Bond, Usman T. Malik, Darrell Schweitzer, Kelly Robson (who I saw again the next weekend at Windycon!), Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, Patrick Nielsen Hayden, Robert V. S. Redick, Shawna McCarthy, C. C. Finlay, Darryl Gregory, Gary K. Wolfe, Dale Hanes, David Boop, Gordon Van Gelder, Brandon Ketchum, Walter Jon Williams, and Arley Sorg.

Then it was on to Branson. The drive, it turned out, was a bit of a disappointment. We stopped in Arkadelphia and went through -- or at least near -- a couple more campuses: Henderson State, and Ouachita Baptist. Then finally up through the mountains -- well, hills -- to Branson. We've been to Branson a number of times, but many years ago. We didn't see all that much of it, though -- the lights downtown were nice, though kind of early! The goal was to eat at one of Guy Fieri's restaurants. It was -- fine -- I mean, really, I had a good hamburger, good comfort food. A bit expensive.

Finally the next morning we headed home, the familiar ride up I-44. We stopped in Rolla at their excellent pie place, A Slice of Pie (in a new more convenient location.) But it was time to be home!

Here's Mary Ann's notes and the key to the songs we played on the way there and back:

"Tear Stained Eye" by Son Volt was picked because of these lyrics,"Sainte Genevieve can hold back the water But saints don't bother with a tear stained eye." Ste. Genevieve is a town just south of St. Louis on I-55.

"Everyday is a Winding Road" by Sheryl Crow. We passed an exit for Kennett, MO, where Crow is from.

"Walking in Memphis" by Marc Cohn. Pretty obvious. We did walk on Beale Street and ate at Dyer’s Burgers which uses grease from 100 years ago. Something like that.

"Jackson" by Johnny Cash and June Carter. Once again, pretty obvious.

"My Hometown" by Bruce Springsteen. This is for our overnight stay in Laurel, MS. That is the town that the HGTV show, Hometown, is set in. I wanted to visit this town since I watch the show.

"The Battle of New Orleans" by Johnny Horton. Our destination for World Fantasy. There are several songs we could have used for NO, but this one has a family connection. (Sort of. Ha!)

"Louisiana Rain" by Tom Petty. Saturday in New Orleans was a very rainy day. We could have used this on Monday when we went to Baton Rouge, as well.

"House of the Rising Sun" by The Animals. We went down to the French Quarter and Rich had a muffaletta and we had beignets at Café Du Monde.

"Crescent City" by Lucinda Williams. We were crossing the Lake Pontchartrain bridge so the lyrics, "And the longest bridge I've ever crossed over Pontchartrain", fit perfectly.

"Baton Rouge" by Magnolia Summer (a St. Louis band.) We did drive through Baton Rouge, so this was a good choice.

"Natchez Trace" by Pavlov’s Dog. We were passing through Natchez, Mississippi on the way home. So pretty obvious. This is a pretty obscure song, I admit.

"Monroe, Louisiana" by Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown. We had to google songs about Monroe, LA. This one came up. I admit I have never heard it before.

"El Dorado" by Elton John. This is a song from The Road to El Dorado. We had to google songs about El Dorado. We stayed the night in El Dorado, AR.

"What I Really Mean", by Robert Earl Keen. It's a musician "touring" song and namechecks a number of places we came close to (and some we got nowhere near!) (Plus Rich likes it a lot.)

"Ballad of Jed Clampett" by Flatt and Scruggs. Because everyone knows the Clampetts came from Silver Dollar City in Branson. We ate at a Guy Fieri restaurant and spent the night.

"Walkin’ Daddy" by Greg Brown. Driving by Jack’s Fork river so these lyrics: "I'm walkin' daddy, where the Jack's Fork river bends/ Down in Missouri, where the Jack's Fork river bends", worked perfectly.

"Meet Me in St. Louis" by Judy Garland. We made it home.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)