The Complete SF of Robert H. Rohrer, Jr.

a survey by Rich Horton

Robert H. Rohrer, Jr., turned 75 in January of 2021. I figured I should do a birthday review for him, and I quickly realized that he only published 16 stories in his short career (about 4 years.) Why not cover his complete works? So I tracked down the magazine issues with stories I hadn't already read (acquiring some duplicates in the process!)

You may well wonder who he is. He published a total of 16 SF or Fantasy stories, between 1962 and 1965. Essentially, these were written during his high school years. Fourteen of the stories appeared in Cele Goldsmith Lalli's magazines, Amazing and Fantastic, and the other two appeared in F&SF. The blurb to his first F&SF story revealed that he was attending Emory University in Atlanta. He became a journalist, and spent his entire career with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

[Mr. Rohrer, if you run across this post, I'd love to hear more about your writing, and your experience with Cele Goldsmith Lalli as an editor, and, also, if you didn't mind, why you never returned to writing SF! Thanks! (I can be reached at rrhorton@prodigy.net.)]

There are only a couple of direct hints to his SF experience, in his own words. One comes from the blurb to his first F&SF story, "Keep Them Happy" (April 1965). It reads: "I don't have much of a biography ... since I haven't been alive very long. I have lived most of my life in Atlanta. I started writing when I was 8; and I intend to go on writing in some form or another until I am dead or otherwise debilitated. My favorite composer is Brahms; my favorite writers are Shakespeare and Ernest Hemingway; my favorite movie is Citizen Kane." I suppose he kept to his intention of writing "in some form" -- alas, that form seems to have been exclusively journalism, as no further SF/F stories eventuated.

The other hint to his writing is a brief piece about the genesis of "Keep Them Happy" that was written for the facsimile edition of that issue of F&SF that was published by Southern Illinois University Press in 1981. He reveals that the story was written in the summer of 1964, after he had graduated from high school and before he went to college. Indeed, he wrote 11 stories that summer! Which explains why so many appeared in a rush in late 1964 and early 1965. Apparently, this was the first story that Lalli ever rejected, so he sent it to F&SF. It's one of his best stories, so I suspect Lalli rejected it more because she already had a lot of his stories in her inventory than for quality. He also notes that his other story "The Man Who Found Proteus" was sparked by his use of the word "protean" in "Keep Them Happy". The inspiration for "Keep Them Happy" is credited to his frustrating inability to ask out a high school crush, though he's quick to emphasize that his situation doesn't resemble the rather dark situation in the story. Influences mentioned are Bradbury, Bloch, Matheson, and Hemingway. And the final sentences of his brief memoir: "That's the way I had fun those days. I had a lot of fun that summer."

I can't honestly say I thought any of Robert Rohrer's stories great, but they did keep getting better, and the work published in 1965 was getting quite interesting. His worldview -- as expressed in the stories -- was pretty dark, perhaps too much so -- there is a certain sense of the cynical teenager in that viewpoint. Still, it would have been interesting to see where he went had he continued to "have fun" in the way he did in those days in his later life.

(Note: his byline was variously "Robert Rohrer", "Robert H. Rohrer", and "Robert H. Rohrer, Jr.".)

Fantastic, March 1962

"Decision" is the first story Robert H. Rohrer, Jr., published. He was 16 when the story appeared, and presumably 15 when he wrote it. That's pretty impressive! The story is minor but not bad. It concerns a team of individuals dealing with a crisis -- and it's soon clear that they are the team operating a politician giving a major speech, but threated by an assassin. From within him! And they must make a split second decision ...

Amazing, October 1962

Last, another Robert H. Rohrer, Jr., story. I’ve covered him before — he was a very precocious author, 16 years old when this story, “Pattern” (his second), was published. He ended up publishing 16 stories in all, mostly in Amazing/Fantastic and in F&SF, all before he turned 20. Then he stopped, apparently losing interest. His father was a physicist at Emory University in Atlanta, GA. Richard Moore reported that he met him (the son)… he had become a journalist and given up SF writing.

His stories showed real promise — not great stuff, but sometimes quite decent: had he wanted to, he might have become pretty good

Anyway, “Pattern” concerns an energy creature in space that encounters a ship with a human crewman. Desperate for sustenance, he tries to consume the “life-impulse” of the human, but its internal “pattern” is too different, and a sort of battle ensues, which the human wins, but at a scary cost. Not a great story, but not bad, with a nicely turned conclusion.

Fantastic, April 1963

"A Fate Worse Than ..." is set in a world where everyone is a Satanist. The protagonist -- named, ironically, Priestley -- summons an angel to try to force it to give him three wishes ... And, of course, the angel finds a way to make it work against Priestley. The story really doesn't work -- the satirical reversal of swearing and praying is vaguely amusing for a bit, but the biter bit reversal is indistinguishable from a typical "Deal With the Devil" story, and the means by which Priestley is doomed is incredibly lame.

Amazing, August 1964

And the other story is “Furnace of the Blue Flame” (6,200 words) by Robert Rohrer. Rohrer had a very odd career. He published 16 stories between 1962 and 1965, mostly in Goldsmith’s magazines (two appeared in F&SF). One story was picked up for one of Judith Merril’s Bests, another for a Best from F&SF volume. The really odd thing is that he was 16(!) when his first story was published, and only 19 when the last appeared. His father was a Physics Professor at Emory University, and the son became a journalist.

“Furnace of the Blue Flame” is actually pretty bad. It’s post-Apocalyptic, about a man traveling the US (complete with silly corrupted place names like Nuyuk, Bigchi, and Lanna), trying to reintroduce learning and knowledge to people. He encounters a village dominated by a vile man who punishes those who resist him with the title furnace – which we immediately realize is a nuclear reactor. The resolution is only slightly more believable than the refrigerator scene from Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

Amazing, September 1964

"The Sheeted Dead" by Robert Rohrer, is SF horror, in which a terrible interplanetary war left a radioactive hell in space. Those who fought were left in space, or buried on Earth, and the survivors on Earth live behind an electromagnetic shield. But then some of the dead soldiers arise ... It's actually pretty well done, with a stark message about the horrors of war finally visited on those who avoided it.

Amazing, October 1964

Robert Rohrer contributes "The Intruders", straight-up space horror. Harley is one of two crewmen on a space ship, but he has succumbed to space fear, and gone mad. He's convinced the ship is his only ally, and he's already killed his crewmate, who tried to lock him up. Now another ship has come to try see what's going on. It's pretty well done "madman tracks down everyone else in the story" stuff, though really anything more than that.

Fantastic, November 1964

"The Man Who Found Proteus" is in a sense Robert H. Rohrer's most successful story, in that it scored a selection to Judith Merril's 10th Annual Best SF anthology. It's fine, but it's not great -- a very short story about a prospector who, one day, finds his mule answering him when he makes a remark. Soon he learns that his mule has been eaten by a shapeshifting character that calls itself "Proteus". This being a Robert Rohrer story -- the prospector isn't going to come out of this well! As I said, it's not bad. By this time in his life Rohrer was beginning to figure out this writing thing.

It turns out another story in this issue is also by Rohrer, though it's bylined "Howard Lyon", apparently hewing to the old tradition that suggested readers would balk at more than one story by the same writer. "Hell" is another short-short, and a thinnish one, in which a nasty man comes to Hell after his death, confident that the sorts of psychological torments that are all the rage these days won't bother him! Well, maybe not, but sometimes the old traditions are the best!

Amazing, January 1965

Many of these late Rohrer stories concern disaster -- and madness -- in space. "The Hard Way" concerns a ship taking a bunch of convicts to Mercury, which overshoots and is drawn inexorably to the Sun. As with many of these stories, the terrible problem is revealed and then ... nothing happens, we simply see the grim results of the initial situation.

Fantastic, March 1965

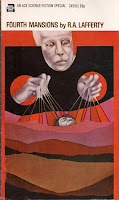

"Iron" is Robert H. Rohrer's first cover story, with the illustration by Paula McLane. It's opens with an alien waking up in the "Mind Prison". Apparently he was imprisoned there after his metal race tried to invade Earth. After 1000 years he is free, and he goes looking for a way to fetch his people and try again to conquer Earth. But to his surprise only robots remain -- apparently all the humans were killed -- and how is a secret, even from the robots. ... the story turns somewhat unconvincingly on the robots' supposed horror at what happened. And the alien's fate is -- well, he's a protagonist in a Robert Rohrer story! Okay stuff, not special.

Amazing, March 1965

Robert Rohrer contributes "Be Yourself". Maxwell finds himself imprisoned -- it seems there's a duplicate of him in prison as well. He's a military man, and there's been a battle with the alien Brgll, who seem to be shapechangers. And now the government isn't sure with Maxwell is the real one! This is headed to a twist ending, guessable but nicely enough executed.

Amazing, April 1965

"Greendark in the Cairn" is a fairly straightforward story of the Captain of a spaceship who becomes convinced he is being driven mad by enemies. His ship is encountering a ship of the enemy (who apparently destroyed another ship with 1500 civilians aboard) and the Captain must make the decision to attack, but his mind is losing it. I have to say I didn't see the point, really -- so, he's going mad, for whatever reason, and as a result he fails to perform his duty. There seems nothing more to the story, to be honest.

Fantastic, April 1965

"Predator" is another disaster in space story, this one a bit more intriguing though I don't think it came off just right. A ship seems to be in trouble on re-entry, but on board the ship all we see is a waiter in pain, and menacing, it seems, some women. The effect aimed at seems psychological horror, and I felt it came close to working but really didn't.

F&SF, April 1965

Robert Rohrer appears for the first time in a magazine edited by someone other than Cele Goldsmith Lalli. "Keep Them Happy" is, I think, one of his best stories. It's set in a future in which the cruelty of capital punishment is intended to be ameliorated by making the convicted individuals as happy as possible before they die. In this case, the murderer is a woman who killed her husband, and the man in charge of her case decides that what she needs is a man to love -- and he will be the one. But, of course, she is guilty -- so her fate is sealed.

Amazing, May 1965

Robert Rohrer’s “The Man from Party Ten” was his second to last story – as noted before, Rohrer was a teenaged writer, who published in Goldsmith/Lalli’s magazines and in F&SF, before abandoning the field, forever, more or less when he went to college. (He became a journalist.) This story is efficiently and cynically told, about a man in charge of a war party during some sort of extended conflict, between nobles and peasants, who encounters a helpful household and takes hospitality from them. The resolution is shocking but, by then, pretty much what we expect.

F&SF, August 1965

"Explosion" ended up being Robert Roher's last published story. And it's another pretty good one. A starship happens to intersect the path of a missile that had been launched but never expended in a previous war. Now it's peacetime, and one result is that the former enemies are sometimes members of crews of human ships. As this story goes on, we see the humans and the alien Maxyd are still unable to trust each other -- with predictable results as the missile approaches ...