Back to an old Ace Double review, which I'm reprinting partly because I learned some interesting new things about the origin of the novel here. Plus of course there are some interesting but distressing new biographical details on the author.

Marion Zimmer was born in 1930 in Albany, NY. She was a very active SF fan from the late '40s, and she published several fanzines as well as numerous exuberant letters in the letter columns of the pulps of the day (I have several issues of old magazines with her letters). She married Robert Bradley in 1949, and they had one son, David, who became a writer, and died in 2008. (MZB's brother, Paul Zimmer, was also an active fan whose letters are easy to find in old SF magazine lettercols, and who later became a reasonably accomplished writer.) The Bradleys divorced in 1964, and Marion married Walter Breen, a fellow SF fan and a noted numismatist, within a month. Breen was already well known as an advocate of pederasty, and MZB certainly knew of his proclivities, and indeed Breen had been banned from at least one SF convention in that time period. Breen had been convicted of pederasty-related crimes as early as 1954, and continued to have trouble with the law, finally going to jail after another conviction in 1990. MZB managed to dodge serious consequences of her husband's activities throughout her life, and she died in 1999. In 2014 her daughter, by Breen, Moira Greyland, accused her of sexual abuse, and in retrospect it seems to me that it should have been clear all along that Bradley was at least negligently complicit in her husband's crimes, certainly aware of them, and now it appears more likely than not that she was a participant herself. (Though I suppose I must add that damning and convincing as the accusations seem, Bradley never did have a chance to defend herself against those that came after her death, though some of her own testimony given during Breen's legal troubles is chilling enough.) This has understandably had a devastating effect on her reputation -- and she was not really a good enough writer to make it likely that her work will long survive the posthumous stain. Jim Hines briefly discusses this, with links to more direct information, in a good blog post here.

Marion Zimmer was born in 1930 in Albany, NY. She was a very active SF fan from the late '40s, and she published several fanzines as well as numerous exuberant letters in the letter columns of the pulps of the day (I have several issues of old magazines with her letters). She married Robert Bradley in 1949, and they had one son, David, who became a writer, and died in 2008. (MZB's brother, Paul Zimmer, was also an active fan whose letters are easy to find in old SF magazine lettercols, and who later became a reasonably accomplished writer.) The Bradleys divorced in 1964, and Marion married Walter Breen, a fellow SF fan and a noted numismatist, within a month. Breen was already well known as an advocate of pederasty, and MZB certainly knew of his proclivities, and indeed Breen had been banned from at least one SF convention in that time period. Breen had been convicted of pederasty-related crimes as early as 1954, and continued to have trouble with the law, finally going to jail after another conviction in 1990. MZB managed to dodge serious consequences of her husband's activities throughout her life, and she died in 1999. In 2014 her daughter, by Breen, Moira Greyland, accused her of sexual abuse, and in retrospect it seems to me that it should have been clear all along that Bradley was at least negligently complicit in her husband's crimes, certainly aware of them, and now it appears more likely than not that she was a participant herself. (Though I suppose I must add that damning and convincing as the accusations seem, Bradley never did have a chance to defend herself against those that came after her death, though some of her own testimony given during Breen's legal troubles is chilling enough.) This has understandably had a devastating effect on her reputation -- and she was not really a good enough writer to make it likely that her work will long survive the posthumous stain. Jim Hines briefly discusses this, with links to more direct information, in a good blog post here.That said, a lot of writers are less than exemplary moral creatures (as with a lot of folks in any profession). It's still worth looking at Bradley's work for its intrinsic value -- she was quite popular, eventually she sold very well, she was a Hugo nominee for her novel The Heritage of Hastur, and her feminist Arthurian fantasy The Mists of Avalon was very well received in some circles. She also edited a magazine, Marion Zimmer Bradley's Fantasy Magazine, as well as two long running anthology series (one consisting of stories set in her world Darkover, the other featuring feminist-oriented stories, Swords and Sorceresses). In her role as editor, she very actively encouraged (and paid!) new writers, and she also gave a lot of advice. To my mind, her advice, and her editorial taste, were of mixed value: she had (I think) limited ideas of proper story construction, and also her fair share of crotchets (for example a dislike of pseudonyms, even though she herself used a number of pseudonyms early in her career, mostly for Lesbian porn); but for all that, she quite sincerely championed new writers, and ushered many of them into publication, some of whom went on to have nice careers. (Though again I must add, I found fairly little of real worth in the many Swords and Sorceresses anthologies I read.)

And what about her fiction? Her most famous series was a long set of SF novels about a lost colony planet called Darkover, where humans developed significant psi powers (to the extent that the novels read a lot like fantasy). I read all the Darkover novels through those that appeared in the mid-'70s, by which time it seemed to me that they grew longer and longer to an excessive point, and also moved in political and psychosexual directions that didn't interest me, and that her skills as a writer did not really uphold. But the early Darkover novels remain good fun -- minor works in context, but fine adventure stories with a romantic cast. By about the mid-60s she was primarly focused on Darkover, but up to that point she wrote a variety of SF novels, mostly similar in tone to the Darkover books (and occasionally she incorporated parts of her early non-Darkover novels into later Darkover stories, even in the case of this book, much of which ended up in The Winds of Darkover).

She was a fairly prolific Ace Double contributor, with 9 Ace Double halves in 7 separate books (not counting this book's later reprint). The book at hand backs her first novel with a story collection. The novel, Falcons of Narabedla, first appeared in full in 1957 in Other Worlds. It is about 41,000 words long, apparently identical to the Other Worlds version or very nearly so. What I didn't know until very recently was that most of Falcons of Narabedla (an early version of it) first appeared in Harlan Ellison's fanzine Dimensions, in 1953 and 1954. (It was to be a five part serial, but Ellison stopped publishing Dimensions before the serial could be completed.) The stories collected in The Dark Intruder total about 37,000 words.

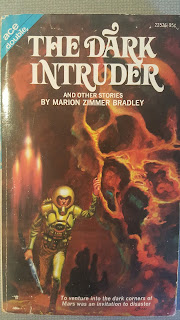

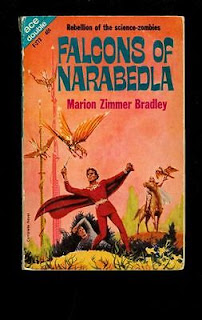

My copy is the second Ace Double edition, from 1972, with covers by Mitchell Hooks and Kelly Freas. The 1964 edition featured these covers, possibly by Jack Gaughan (at least the one for The Dark Intruder looks like him, and he did do the interiors):

What follows is what I wrote about this book a number of years ago.

Falcons of Narabedla is on the one hand a very pulpy short novel, with a hackneyed basic premise (man snatched out of time into another world), and such standard features as anachronistic sword-fighting, aristocratic societies and rebellion, and an overly rapid conclusion. On the other hand, there are some pretty intriguing ideas that could have stood further development, and the book as a whole reads rapidly and excitingly. In the end it was kind of frustrating -- it could have been decent stuff, but it really isn't very good.

Falcons of Narabedla is on the one hand a very pulpy short novel, with a hackneyed basic premise (man snatched out of time into another world), and such standard features as anachronistic sword-fighting, aristocratic societies and rebellion, and an overly rapid conclusion. On the other hand, there are some pretty intriguing ideas that could have stood further development, and the book as a whole reads rapidly and excitingly. In the end it was kind of frustrating -- it could have been decent stuff, but it really isn't very good.It opens with Mike Kenscott camping in the Sierra Madres with his younger brother. Mike is an electrical engineer who has been acting strangely since he had an accident with some equipment he was working, and he has had occasional odd "memories" of strange birds and the like. Suddenly he finds himself waking in a strange tower, looking over a much changed Sierra skyline, with two suns in the sky. The people with him call him "Adric", and he has no idea who they are. And a look in the mirror shows a much different man.

Slowly he learns that he is in the body of a man named Adric, far in the future. Adric seems to have been an ambitious lord of this land called Narabedla, but he has been under the sway of a beautiful woman called Kamary. The people who have woken him, a veiled androgynous figure called Gamine and an ancient man called Rhys, seem somehow opposed to Kamary, and there is also talk of the Dreamers, and of a man named Narayan. Further encounters with Adric's jealous brother Evarin, a "Toymaker", and then with Kamary and her zombie-like slaves, only serve to increase the confusion. And the partial return of Adric's memories and even consciousness helps little.

Eventually he agrees to join a mission to the Dreamer's Keep, where by some horrifying means the aristocrats of Narabedla gain power from the sleeping, imprisoned, Dreamers linked to them. But on the way he is kidnapped by Narayan, and comes to in Narayan's rebel camp, along with the beautiful Cynara, an apparently sympathetic woman who had accompanied the group heading for the Keep. Narayan and Cynara turn out to be brother and sister, and it transpires that Adric and Narayan were close friends -- indeed, Narayan was Adric's linked Dreamer, and the source of his power. But Adric had chosen to free Cynara and then Nayaran, an act which precipitated Kamary's taken control of him, and indeed her sending his consciousness into the past. Now Michael Kenscott is in charge, and he agrees to help Narayan's people in their quest to free the caged Dreamers and overturn Kamary's group. But then Adric's consciousness returns to control, and he has reverted to the brutish lord who wishes to return Narayan to his prison. Pretending to be Kenscott, he leads Narayan's group into a trap -- and only the sudden (and quite unexplained) appearance of Kenscott's physical body for Kenscott to return to makes it possible to resist him.

I've skipped a few details such as the title birds, huge falcons that are mentally controlled by the aristocrats. I've also glossed over something that annoyed me but probably wouldn't bother lots of people -- Bradley's character names just seem stupid. One character has three short first names (Mike Ken Scott). One is named after a famous Indian writer (Narayan). One name seems a description: Gamine. (I suppose it would be unfair to mention that another name seems like a Toyota, as there were no Camrys when this book was written.) But no matter. The story is resolved fairly predictably, and too rapidly. The characters are neatly paired off, the bad guys are only punished a little, there is new hope for Narabedla, etc. etc. Ultimately a pretty minor book, but it does hint at some of what made the best of Bradley's Darkover novels pretty good stuff.

Marion Zimmer Bradley's short fiction career has a slightly odd shape. She first made her name as a fan, writing colorful letters to magazines like Thrilling Wonder Stories, using pseudonyms like Astara. In 1953 she sold two stories to the very low end and short-lived magazine Vortex, and beginning in 1954 she started selling more regularly to better magazines (though very rarely to the top magazines). By the late 50s she was writing novels, and her short stories ceased in 1963 as she focused on her Darkover books. She began writing more short fiction in 1973, a Tolkien pastiche called "Letter to Arwen", then in the 80s produced a number of short stories, seemingly mostly in support of her projects such as the Friends of Darkover books, as well as Thieves' World stories.

The Dark Intruder and Other Stories, then, appearing after her first run of short fiction had ceased, serves as a documentation of that phase of her career. Except for the title story, these are fairly short pieces, definitely SF and not Fantasy, turning on cute and sometimes mordant ideas.

"The Dark Intruder" (15,000 words) (Amazing, December 1962, as "Measureless to Man", a far better title) -- Under its original title, this story appears on my list of stories with titles from "Kubla Khan". It's set on Mars. Andrew Slayton is part of the third archaeological expedition to the deserted ancient Martian city called Xanadu. The members of the previous two expeditions died violently. Andrew stumbles into the desert near the city and finds himself possessed by the mind of an ancient Martian. Somehow, due to his own strength and the restraint of his possessor, he retains his sanity. He learns a secret about the dying Martian race, and must try to find a solution for their unique problem. Not a bad story.

"Jackie Sees a Star" (1900 words) (Fantastic Universe, December 1954) -- a young boy is in telepathic contact with a young alien on a distant star. OK for its length.

"Exiles of Tomorrow" (2700 words) (Fantastic Universe, March 1955) -- in the future criminals are punished by exiling them to the past, where they are to live alone. One couple manages to arrange to be exiled to the same time, and they have a child. The boy grows up and meets a very unusual man ... leading to a shock ending that didn't work for me. Nice basic idea, though.

"Death Between the Stars" (6800 words) (Fantastic Universe, March 1956) -- also uses an idea from "The Dark Intruder" -- aliens "possessing" humans somewhat benignly. A woman needs to take a starship back to human space, but the only berth is with an alien. The aliens are hated by humans and any contact with them is regarded as vile, for totally unconvincing reasons. The alien is mistreated by the crew and the woman must overcome her misgivings to try to save him. As the title hints, not successfully -- except in an unexpected way. Too much of the motivating force of this story was auctorially engineered, very implausibly, to work for me.

"The Crime Therapist" (3700 words) (Future, October 1954) -- criminals can be cured of the psychological problems that lead to their crimes by acting them out, as for example a potential murderer can kill an android made up to look like his intended victim. In this story, a husband who wants to kill his wife is allowed to kill an android looking like her -- and after all the consequences of that act occur, he is indeed no longer a danger to society. Silly.

"The Stars Are Waiting" (4100 words) (Saturn, March 1958) -- India has closed its borders and destroyed its weapons. The CIA needs to know what's going on, and now their spy has returned, unable to talk coherently. At the cost of his life, they finally hear what he has learned. The solution is wish-fulfillment to the max.

"Black and White" (3900 words) (Amazing, November 1962) -- After the holocaust, the last man on Earth is black, and the last woman on Earth is white. Can they possibly marry and further the species? That would be too silly for words, but MZB is a little better than that -- the real conflict is that the black man is also a Catholic priest, struggling with his celibacy vows, and using race as an excuse. Then they encounter one more man -- unfortunately he's a moronic Southerner, and the results are bitter. Not too bad of a story, especially for the time.

Overall, a collection of middle-of-the-road pieces, the work of a competent pro who doesn't really seem to have been at her best at shorter lengths. Nothing here is as good as the early Darkover novels (which I enjoyed until the Brain Eater seemed to strike around the time of The Mists of Avalon and the Free Amazon books).

No comments:

Post a Comment