At one time I wondered if it would make sense to compile a list of elephant-like intelligent aliens in SF stories. This was about when Mike Resnick published "The Elephants on Neptune" (which I hated). There are those beasties in Niven&Pournelle's Footfall, which I've never been able to read. And there are the mammoths in Stephen Baxter's awful Silverhair and sequels. Weren't there intelligent elephants in Silverberg's Downward to the Earth (at least I thought that was pretty good)?

At one time I wondered if it would make sense to compile a list of elephant-like intelligent aliens in SF stories. This was about when Mike Resnick published "The Elephants on Neptune" (which I hated). There are those beasties in Niven&Pournelle's Footfall, which I've never been able to read. And there are the mammoths in Stephen Baxter's awful Silverhair and sequels. Weren't there intelligent elephants in Silverberg's Downward to the Earth (at least I thought that was pretty good)? Any others?

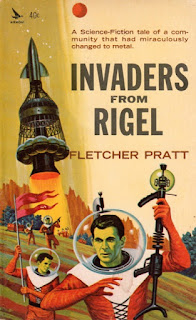

So, the record of elephants in SF is maybe not so great, eh? And perhaps the WORST of all SF elephant stories is Fletcher Pratt's Invaders from Rigel, which I read and reviewed about the same time as Resnick's story appeared. I bought the book used a long time ago, in part because of Pratt's reputation (mainly, perhaps, derived from his de Camp collaborations). Danger signs, however, were immediately apparent. The book was published in 1960, and Pratt died in 1956. It was published by the salvage imprint Airmont, famous for publishing some dreadful stuff, though also some of de Camp's Krishna stories.

At first I thought it a late novel by Pratt, but that is only because the book came out in 1960. However, it was first published as "The Onslaught from Rigel", in Wonder Stories Quarterly, Winter 1931. It was reprinted in a 1950 edition of Wonder Story Annual which I assume was a reprint publication featuring backlist stuff from Wonder Stories.

I thought Pratt was a good writer. I thought that because of his de Camp collaborations. I am also told that later stuff like Double Jeopardy and especially The Well of the Unicorn is OK. Well maybe. But when he wrote for the pulps in the '30s he was irredeemably awful. I had earlier read Alien Planet, first published as "A Voice Across the Years" in the Winter 1932 Amazing Stories Quarterly, listed there as a collaboration with I. M. Stephens (who was his wife, Inga Stephens Pratt, a quite significant illustrator). Inexplicably, Ace reprinted this book as late as 1973. That book was awful, though oddly ambitious in being a rather satirical look at humans and their politics. Ham-handedly satirical, mind you, but at least it sort of tried. Invaders from Rigel doesn't even try anything so daring.

The story opens with one Murray Lee waking in his New York Penthouse. He soon realizes he is all metal. His roommate is as well. They tromp about the city for a bit, finding a few more live metal people, and many dead ones. This doesn't seem to bother them much. Before long alien birdlike creatures are attacking, and some people are carried away by the birds. It turns out that a comet just crashed with the Earth. That must have turned everybody to metal. Jokes are made about how they like to drink motor oil now, and their "food" is electric current. But the birds are a problem: they seem to be intelligent and malevolent. After trying to activate a destroyer, they are discovered by some Australians, who have not been turned to metal, though their blood has cobalt instead of iron now, so they are colored blue. The metal Americans join with the Australians to fight the bird menace, but it soon turns out that the real menace is a race of elephant-beings from Rigel, who are using the metal men, as well as metal apes, as slaves to harvest "pure light" from the core of the Earth.

Right.

The humans start to fight the Rigellians, but the aliens have a "pure light" weapon. Then a new character is introduced: a pilot who was captured by the elephants. He managed to escape (his ordeal is given several chapters), carrying the knowledge that lead blocks the alien super ray. Yeah. The novel concludes with a number of chapters of arms escalation, as the humans invent anti-gravity (because gravity is just like electricity, and so basically, as described, antigravity can be produced by ionization). Pointless to continue. By the end, the elephants have been vanquished (whoda thunk it?), and the metal people returned to normal. Also, there are a couple of totally unconvincing and uninvolving love affairs.

Oh, and most of the world's population is dead, and nobody really cares.

A couple of quotes which struck me particularly:

"I've got it, folks!" he cried. "A gravity beam!"

[chapter break, natch!]

"A gravity beam!" they ejaculated together, in tones ranging from incredulity to simple puzzlement.

"What's that?"

"Well, it'll take a bit of explaining but I'll drop out the technical part of it." [I'll bet you will!]

[some blather about how light and matter and electricity and gravity are all the same. Einstein said so, right!]

then:

"What was it in chemical atoms [as opposed to the other kind, I guess] that was weight? It's the positive charge, isn't it? ... Now if we can just find some way to pull some negative charges loose ..."

See? Antigravity by ionisation! If we only knew!

Later on one of the metal women is trapped with one of the metal men in a prison. They are a couple of cages away. He needs a safety pin, and she has one. So: "She swung with that underarm motion that is the nearest any woman can come to a throw." ! Let's tell Dot Richardson!

Oh, well, silly to complain further, or at all really. I'm sure Platt wrote this in about two days.