Ace Double Reviews, 101:

Time Thieves, by Dean R. Koontz/

Against Arcturus, by Susan K. Putney (#00990, 1972, 95 cents)

a review by Rich Horton

This is one of the latest Ace Doubles, appearing about a year before the program ended. Don Wollheim and Terry Carr had both left Ace a year earlier. Fred Pohl was editor until June 1972, about when

Time Thieves/

Against Arcturus appeared, so presumably he acquired these novels.

|

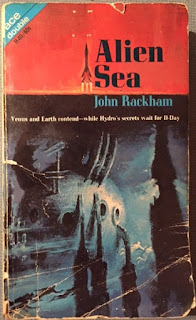

| (cover by David Plourde) |

This book pairs an early novel by a writer who has since built a pretty major career with the only novel by a very obscure writer. Both novels have aspects of interest but are fairly flawed. The copy-editing is noticeably poor (especially in the Koontz novel): while Ace's editing and production standard had never been great, I did feel this was worse than in preceding years, and I wonder if the company's turmoil at the time was a factor (Ace had just been acquired by Grosset and Dunlap).

|

| (Cover by Mart?) |

One other production mishap, I'm pretty certain, involves the covers. They seem to have been switched. That is, while neither cover illustration is particularly representative of a scene in either novel, the one for

Time Thieves seems to fit

Against Arcturus reasonably well (hot human spy, large humanoid aliens, spaceships with laser-type weapons); while the one for

Against Arcturus could, at a bit of a stretch, work for

Time Thieves. (The art could, I suppose, have been random stuff that was just slapped on the books.) The artists are hard to figure out: the cover for

Time Thieves is signed Plourde, apparently David Plourde. The other sided is signed Mart, I suspected possibly truncated from Martin. I don't know who that could be, and for that matter I know nothing about David Plourde.

Time Thieves was a fairly early Dean Koontz novel, his first (

Star Quest) having appeared in 1968. He worked steadily in a number of genres for the first decade or so of his career, under numerous pseudonyms, before hitting it big with such novels as

Whispers, in 1980. Most of his work since then has been suspense thrillers, many of them bestsellers.

Time Thieves opens with Pete Mullion waking from a strange dream while sitting in his car in his garage. He assumes he has just driven home from his cabin in the woods, and he goes into the house, and realizes he doesn't remember anything for some undetermined time. And then his wife comes in and yells at him for abandoning her for 12 days.

He begins to try to tackle the mystery -- asking the police what's going on, going back to the cabin, visiting a motel he apparently stayed at. There is another period of amnesia, and sighting of mysterious people. Eventually he directly encounters one of the strange people -- who turns out to be a robot.

Pete and his wife are deep in the mystery by now. Pete begins to realize he is developing telepathic abilities. And the robots keep insisting that he give himself up -- for his own good. Also, they sinisterly promise not to hurt him. And his telepathic ability allows him to sense the minds of the robots -- and to realize they are controlled by another mind, apparently belonging to an alien.

The novel resolves with a chase scene or two, a kidnapping, and then finally a talk between Pete and the aliens, whereby their true motives are revealed. And Pete makes his own decision ...

The book is well-told at the plot level -- it moves quickly, holds the interest, has some interesting ideas. I thought the resolution -- the aliens' motivations -- a bit lame. And the prose is inconsistent at best -- there are some real howlers. (Some of this may be laid at the hands of Ace's terrible copyediting.)

Against Arcturus is a stranger book. We begin on the planet Berbidron. A couple of natives (who call themselves Sarbr) see an Earth ship landing, and when they approach, they get shot. Those two leave, and a few more aliens investigate (including one called intriguingly "Arlem the Actor (soon to be Arlem the Traitor)". They instantly learn the human language (Latin), and quickly agree with the human proposal that they become civilized. Within 5 years they have built several cities, and have become involved in a dispute over the control of their planet: the first visitors were from the Earth-New Eden Alliance, but it has been taken over by the apparently more authoritarian human colony of one of Arcturus' planets.

This first section is told in an engaging fashion, resembling to a small degree writers like Ursula Le Guin and Eleanor Arnason, using journals, giving hints of the Sarbr society. It seems we are on the route to, perhaps, an anthropological bit of SF, where the human invaders will eventually get their comeuppance as they (and we, the readers) learn the true nature of the Sarbr. And, in a way, that's what happens. But we get there in a different way. And much of the aim of the book seems somewhat satirical -- making fun of human civilization partly by having the Sarbr who happen to be interested in it playact a version of it.

Most of the rest of the story is told by Beth Goodrich, a woman from New Eden who is recruited, somewhat despite her misgivings, to come to Berbidron and try to foment a rebellion against the Arcturans, who now control the cities on Berbidron. Beth, apparently, has experience at this -- she has spent time protesting the government on New Eden. She also has a vaguely telepathic/empathic ability (which she calls sympathy) -- she can understand the thoughts and feelings of humans, and even animals (such as her pet squirrels) and, it turns out, trees. But not the Sarbr. She ends up joining the Berbidron Liberation Front, where she meets the aforementioned Arlem the Traitor (so-called because he is actually working for the Arcturans).

She ends up bouncing around the planet, noticing but mostly ignoring hints that the nature of things on Berbidron is quite different than the humans seem to think, and getting herself killed. And resurrected, with a new name. Eventually the real plans of the Arcturans are revealed, which are pretty awful, and it becomes urgent to actually stop them. (Before that it seemed like a game, which is really the way the Sarbr seem to approach it.) Finally Beth (or, that is, Natasha) and some of her Sarbr friends make a journey to a desolate part of the planet, and she finally learns the truth about the Sarbr -- and, more importantly, about humanity.

Some of all this is kind of silly, though interesting. Some is fairly funny. Some is just busy. The science, as well as the timeline, really doesn't make much sense, but maybe that doesn't matter much. I thought it on balance an intriguing but not really successful effort, and I'm surprised the writer never did much else. She did write a graphic novel about Spiderman, which was published with illustrations by Berni Wrightson. And there is at least one short story (or perhaps a novel excerpt) available online (apparently posted by the author, some time ago). And not much else seems to be generally known.

I asked for help from a group of experts on the field that I hang out with, and Art Lortie came through wonderfully. He found that Susan K. Putney was born in 1951, in Iowa, once ran for Congress in Nebraska as a Libertarian, once owned a comic book store, lived in Phoenix for a while, and now lives in my own state, Missouri.

The book opens in purest YA hard SF mode, with a group of college-age kids trying to make their way into space. It seems that most of the trick is to acquire a space bubble, or "bubb", which is what it sounds like -- not much bigger than person-sized, a bubble based on a super-plastic, with plenty of air production capacity, in which someone can survive for a pretty significant time in empty space. The group includes a diverse(-ish) mix -- one woman, a rich kid, a handicapped kid, a couple of football star twins, a delinquent, a couple more, plus the eventual viewpoint character, Frank Nelsen, the straight-arrow honest type. This first part goes on for 50 pages or so, pretty effectively, as the "bunch" (their name) navigates such issues as making the "bubbs", learning how to use them, passing the required space fitness tests, raising the needed money, and so on. The girl member drops out, realizing the the regular Space organization is desperate for women, and another guy washes out for lack of psychological fitness, and one member has to deal with his mother who won't let him go.

The book opens in purest YA hard SF mode, with a group of college-age kids trying to make their way into space. It seems that most of the trick is to acquire a space bubble, or "bubb", which is what it sounds like -- not much bigger than person-sized, a bubble based on a super-plastic, with plenty of air production capacity, in which someone can survive for a pretty significant time in empty space. The group includes a diverse(-ish) mix -- one woman, a rich kid, a handicapped kid, a couple of football star twins, a delinquent, a couple more, plus the eventual viewpoint character, Frank Nelsen, the straight-arrow honest type. This first part goes on for 50 pages or so, pretty effectively, as the "bunch" (their name) navigates such issues as making the "bubbs", learning how to use them, passing the required space fitness tests, raising the needed money, and so on. The girl member drops out, realizing the the regular Space organization is desperate for women, and another guy washes out for lack of psychological fitness, and one member has to deal with his mother who won't let him go.