Part I: Seattle, and the drive to Spokane

(This part of the report will perhaps be of less interest to those who want to hear about Worldcon.)

I decided some time ago to attend Sasquan in Spokane, WA, the 2015 World Science Fiction Convention. As a convention-goer, I'm a bit of a homebody: I regularly go Conquest, Archon, and Windycon, which are, respectively, about 250 miles, 30 miles, and 275 miles from my home in Webster Groves, MO. The only Worldcon I've been to was Chicon III in 2012, also less than 300 miles away. I absolutely loved my time at Chicon, and I really wanted to make it to LoneStarCon in 2013 in San Antonio, but between my work schedule and the fact that a drive to San Antonio would have taken two days (even with a stopover in my brother's house in Dallas), I just couldn't make it. And Loncon in 2014 was simply not workable economically -- a great shame as we at Lightspeed won our first Hugo there. So I figured no matter what, I'd make the trip to Spokane work (helped, to be sure, by frequent flyer miles increased by that previously mentioned work schedule). This became even more urgent when Lightspeed was again nominated for a Hugo.

This trip was better than the one to Chicago because my wife Mary Ann came along. (Of course it was also better because I've been to Chicago a million or so times, considering I was born in the suburbs.) We decided to fly to Seattle first, for some pure quill tourism. We ended up flying in on Southwest fairly late on Saturday, arriving, well, early on Sunday, at 2:30 AM. This was partly due to Southwest: our first leg out of St. Louis was delayed for a couple of reason, finally because the plane was overweight and 16(!) passengers had to get off (in exchange for a dinner, night at a hotel, replacement ticket, and $300). We almost missed our connection in Denver -- fortunately the gate was only a couple down from our arriving flight, and even then we might have been late except the Denver to Seattle leg was late as well. We were staying in a Hampton in Tukwila, pretty near the airport (much cheaper than staying in the city).

The next day we got up (a bit late perhaps) and drove into the city, with the object of visiting Pike's Place Market. We had to park a bit of a walk from the Market, but we made it ... it's an enjoyable place to visit. They have a Left Bank Books (unrelated to the institution in the Central West End of St. Louis I assume) ... walked into that (a bit on the "crazy left" side if you ask me, and not a terribly impressive SF section, but there you are!). We ate at an OK restaurant in the Market, Pike's Place ... We were getting a bit tired, and the car was a bit of a hike, so I walked back to it and, after negotiating some slightly insane traffic, picked Mary Ann up on the waterfront and we headed back to the hotel, to veg out and watch the PGA.

Then we figured Tacoma, about 30 miles south, would be a nice change, so we wandered that way, and decided Point Defiance would be a nice place to visit. This is a peninsula jutting into the Puget Sound, just NW of Tacoma, all a park, with a zoo. We drove around the Point, stopping at several pullover places, with good views of the Sound and Vashon Island, and even at some points a view of the famous Tacoma Narrows Bridge (or, that is, its replacement). We ate at a restaurant just prior to Point Defiance, Duke's Chowder House. Very good.

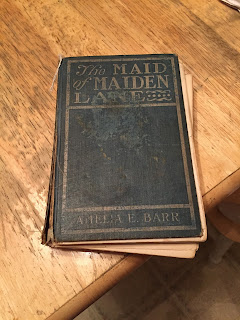

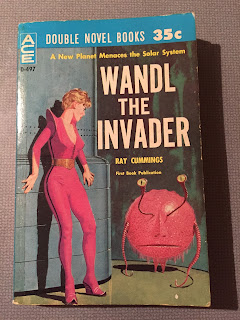

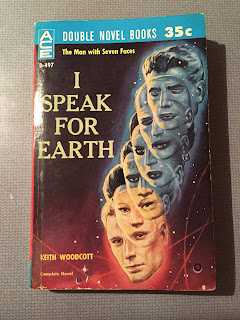

On Monday we first went to the EMP museum, which was founded by Paul Allen, originally as a Science Fiction museum. It is now devoted to Entertainment, Music, and Pop Culture, but SF is a big chunk of the Pop Culture aspect. There was an exhibit of costumes from the Star Wars movies, sections devoted to SF and to Fantasy and to Horror, a small wall for the SF Hall of Fame. It was a bit too media-oriented, and too shallow for my taste. There were also exhibits on a couple of Rock music icons from Seattle: Jimi Hendrix and Nirvana, and a fairly interesting guitar display. The Space Needle is right next door ... we contented ourselves with pictures. Then decided to visit Pike Place Market again, this time to do some slightly more devoted shopping. At a used book store I bought an omnibus of John Barth's first two novels, The Floating Opera and The End of the Road. We had lunch at Steelhead Diner, a place highly recommended by a couple who came to our church who had just moved to St. Louis from Seattle. It was very good. Then we took a ride on the Ferris Wheel on the waterfront, nice views of both the city and the sound.

On Monday we first went to the EMP museum, which was founded by Paul Allen, originally as a Science Fiction museum. It is now devoted to Entertainment, Music, and Pop Culture, but SF is a big chunk of the Pop Culture aspect. There was an exhibit of costumes from the Star Wars movies, sections devoted to SF and to Fantasy and to Horror, a small wall for the SF Hall of Fame. It was a bit too media-oriented, and too shallow for my taste. There were also exhibits on a couple of Rock music icons from Seattle: Jimi Hendrix and Nirvana, and a fairly interesting guitar display. The Space Needle is right next door ... we contented ourselves with pictures. Then decided to visit Pike Place Market again, this time to do some slightly more devoted shopping. At a used book store I bought an omnibus of John Barth's first two novels, The Floating Opera and The End of the Road. We had lunch at Steelhead Diner, a place highly recommended by a couple who came to our church who had just moved to St. Louis from Seattle. It was very good. Then we took a ride on the Ferris Wheel on the waterfront, nice views of both the city and the sound. Finally we took a sailboat ride into the Sound. It was a great deal of fun. The Seattle area is really pretty. I did also get a view of a restaurant I'd eaten at on a previous (business) trip, Salty's, which is across from the port part of the city. After that we were tired and ready to go back to the hotel, though first we drove to West Seattle just to see it.

I should mention parking perhaps ... only to say that it's pretty expensive. Not a surprise in a big city, of course.

So the next day was "drive to Spokane day", but we had plenty of time, so we decided to make a stop on the way for a good view of Mt. Rainier. (We'd already seen the mountain quite clearly from Seattle, to be sure.) We went to a ski resort (off season of course), Crystal Mountain. They let you ride up their gondola lift (for a price of course), to the top of one of their mountains (perhaps 7000 feet?), which gives an excellent view of Mt. Rainier and of many of the other Cascade volcanoes such as Mt. Adams. There's a restaurant at the top, a bit pricy for only OK quality, though I did rather like the wrap I had. Lots of ladybugs up there too.

We continued towards Spokane, taking the scenic route as a result of the diversion to Crystal Mountain. We went through Yakima (which is a larger town than I had imagined), before turning up to I90 then East to Spokane. The foliage in Eastern Washington is much different than in the west -- much much drier. And of course there have been fires in the area, though we didn't see anything on the drive (but later in Spokane the presence of fires became atmospherically clear!) Checked in at the hotel (Red Lion River Inn, right on the Spokane River, quite near to Gonzaga University). The hotel staff were effusive in their delight at having the Convention in town -- that's one thing in being in a middlish-sized city, you get a lot more attention from the locals.By then it was after 730, so we just went out to get dinner (Mexican food at a very loud place called Borracho -- not my favorite place, really), and so to bed.