Thursday, June 26, 2014

Old Bestsellers: Rogue Male, by Geoffrey Household

Rogue Male, by Geoffrey Household

A review by Rich Horton

Geoffrey Household's Rogue Male is a classic thriller. It's not really forgotten, but it has, I think entered a phase of slow drifting out of any sort of general consciousness. Though perhaps not: it has been reprinted as recently as 2007, and it has been cited by David Morrell as a significant influence on First Blood (the Morrell novel that introduced Rambo to the world).

Household was a British writer, born 1900, died 1988, who spent some time in the US "just in time for the Depression". He began writing in the US, then returned to England. This is his second novel, published in 1939. He spent the War as an Intelligence Officer in Rumania, then returned to a fairly successful career writing. Rogue Male remains his most famous novel, though Arabesque (made into a movie with Gregory Peck, as I recall) is also well known. Rogue Male itself has been filmed at least twice, as Man Hunt in 1941 and as Rogue Male for TV in 1976.

Rogue Male opens with the never named first person protagonist aiming a rifle with a telescopic sight from 550 yards at a certain Head of State. It's never made precisely clear who that is -- a country on one side or the other of Poland, which leaves two pretty evil candidates as of the late 30s. The cover of my 1977 Penguin edition shows a picture of Hitler in the crosshairs, which to be fair is pretty likely who Household intended. But the book takes care never to reveal which of Hitler or Stalin was the target -- on purpose, I think -- and I think the cover illustration is a blunder.

The protagonist claims he had no intention of shooting -- he was just "stalking the most dangerous game" for the fun of it, to see if he could be successful. This doesn't play well with the local secret police, who torture him and leave him for dead. But he rather incredibly escapes, and makes his way down a river, soon pursued by his enemies. He stows away on a boat for England, but soon is again pursued. When he is forced to kill one of his pursuers, he becomes wanted for murder by the British police. He flees to the country, planning to literally hole up for the duration. But even his careful plans aren't quite enough -- some bad luck leads to the British police getting a lead, and though he can elude them, the bad guys are able to track him down.

It's pretty good stuff. Exciting, not too ridiculously implausible, and at least somewhat interested in exploring the moral basis of the protagonist's decisions. (Though there is plenty of guff, too, in particular lots of stuff about the wonderful ineffable qualities of the English Upper Class.) (Some of the book is the protagonist's own coming to terms with his real motives and intentions.) It helps of course that the protagonist's target is a real-life maximally evil sort -- even if we continue to disapprove of his assassination attempt, it's hard not to sympathize at some level. The book is also quite dryly funny on occasion. The ending is interesting in retrospect. The protagonist, having again escaped, decides his only recourse is to finish the assassination job. And there the book ends. But it was published in 1939. Then it was a very "open" ending. Now -- any time since 1945 really -- the ending has closed somewhat -- we can only conclude that the protagonist failed in his attempt and was presumable summarily executed. (Though there was a sequel, Rogue Justice, published much later (in 1982).)

Thursday, June 19, 2014

Ace Doubles: The Blank Wall/The Girl Who Had to Die, by Elisabeth Sanxay Holding

The Blank Wall/The Girl Who Had to Die, by Elisabeth Sanxay Holding

a review by Rich Horton

This blog is primarily about "old bestsellers", but other "old" books are interesting to me, and one of my favorite publishing lines of the past is Ace Doubles, inexpensive paperbacks featuring two books printed back-to-back (or dos-a-dos), each upside down relative to the other. These appeared between 1952 and 1973. They are most famous in the Science Fiction genre, but a number were printed in other genres, especially mysteries and Westerns.

I went to an antique mall in Kansas City after attending ConQuest (a science fiction convention) a few weeks ago. One stall had a bunch of old paperbacks, including an Ace Double. This one intrigued me because it was a mystery by an author I had never heard of, Elisabeth Sanxay Holding. The covers including some impressive quotes praising Holding, from places like the New Yorker; as well as one from Raymond Chandler: "She's the top suspense writer of them all."

I went to an antique mall in Kansas City after attending ConQuest (a science fiction convention) a few weeks ago. One stall had a bunch of old paperbacks, including an Ace Double. This one intrigued me because it was a mystery by an author I had never heard of, Elisabeth Sanxay Holding. The covers including some impressive quotes praising Holding, from places like the New Yorker; as well as one from Raymond Chandler: "She's the top suspense writer of them all."I confess I had visions of rediscovering a completely forgotten master of the pulp era. But when I researched Holding I learned that plenty of people are way ahead of me. That's not to say she wasn't somewhat unfairly forgotten. She was born in 1889, died in 1955. She began her writing career as a romance novelist, but switched to mysteries during the depression. Her novels sold fairly well, and she was well-praised. She wrote at least one YA fantasy, Miss Kelly, which Anthony Boucher praised in the pages of F&SF. But she did seem to be mostly forgotten after her death.

That said, The Blank Wall, generally considered her best novel, had already been filmed in 1949 as The Reckless Moment (starring Joan Bennett and James Mason). It was filmed again in 2001 as The Deep End, starring Tilda Swinton. (This was pretty much Swinton's "breakout" film, "breakout" here being relative to Swinton's career -- that is, she didn't become a major movie star, she just moved from a well-respected indie actress to an even more respected Hollywood actress, who would contend for Academy Awards (and, indeed, eventually win one).) More recently, a number of Holding's books have been reprinted by Persephone Press and by Stark House (the latter, neatly, are double editions). The Blank Wall was even featured in a Guardian list, in 2011, of the "Ten Best Neglected Literary Classics". She has been called "The Godmother of Noir". So she's not forgotten, and indeed I think her reputation is slowly increasing at last.

My Ace Double includes two novels, The Girl Who Had to Die (1940) and The Blank Wall (1947). The Girl Who Had to Die was first published by Dodd, Mead; and The Blank Wall by Simon and Schuster. There was a 1950 Pocket Books edition of The Blank Wall, with the classic blurb: "Playing with jail bait earned him a date with death!". (In perfect blurb fashion, this is not at all false, but neither does it describe the book in any useful way.) The Ace Double edition was part of a series of six Holding doubles that appeared in 1965.

Both books are told in tight third person, and spend much of the time in the protagonist's mind, exploring their internal reactions. This serves to portray the character quite effectively, at least in The Blank Wall -- one of the weaknesses of The Girl Who Had to Die is that the main character never really convinces.

The Blank Wall's protagonist is Lucia Holley, a New York housewife in her late 30s, who has rented a house on Long Island, on the ocean, while her husband is away. (He's an officer in the U.S. Navy in World War II.) She lives with her two children, 17 year old Bee and 15 year old David; as well as with her elderly father (who is English) and an African-American maid, Sibyl. Bee is going to art school and New York, and Lucia is upset that she has been seeing a 35-year-old married man, Ted Darby. Darby shows up at their house, lurking by the boathouse, and Lucia's father goes out to confront him, and (without knowing it) accidentally kills him. Lucia discovers the dead body the next morning and, to protect her father and Bee from scandal, hides the body on an island.

Of course this doesn't work, for multiple reasons. The body is soon discovered. Darby, it turns out, is every bit as bad as Lucia thought, a gangster and a dealer in porn (no doubt his intention for Bee was to make her a model). For a time it seems the crime might be pinned on a ganster associate of Darby's. But Lucia has further troubles: a couple more gangsters show up trying to extort money from her in exchange for some embarrassing letters from Bee to Darby that Darby had sold them. And a neighbor saw Lucia taking the boat out with Darby's body, though not closely enough to identify her. But that -- and other aspects of the crime -- is enough to raise the suspicions of the investigator, Lieutenant Levy (who is apparently a character in a number of Holding's books).

Then Lucia starts to get a bit attached to one of the blackmailers, Martin Donnelly. He seems to like Lucia, and offers to pay off his partner so that he'll stop the blackmail, and he even sends them some black market meat. (One of the excellent minor points of the novel is its depiction of the difficulties of household management because of the rationing during the War.) Their meetings, though basically innocent (if hinting at suppressed sexual attraction) infuriate David and Bee, who suspect the worst.

There is another killing, and another desperate attempt to hide a body, and Lieutenant Levy seems to know pretty much everything ... well, I won't detail the ending. But the book works beautifully. Lucia's actions, each on the face of it understandable, if often foolish, keep winding the noose tighter around her. Her motivations ring true, her inner life -- missing her husband while worrying she's forgetting him, fretting that she hasn't raised Bee right, frustration at her relative incompetence as a housekeeper (only Sybil really keeps the household going), her isolation from the neighbors -- is excellently portrayed. The prose is quite fine as well. As noted, Lucia is depicted very well, and so is Sybil (who has her own sad back story, a husband unfairly imprisoned (in a way only too understandable for African-Americans of that time). The children are perhaps a bit caricatured, especially Bee; and Martin Donnelly's unexpected nobility, though affecting and well-described, seems perhaps a bit fortuitous. As I said, the background details of wartime life on the home front are very well done. This is a novel that deserves its reputation.

The Girl Who Had to Die is less successful. The protagonist is Jocko Killian, a clerk from New York who has spent a year in Argentina, and is returning in the company of an unstable and alcholic 19 year old girl, Jocelyn. Jocelyn tells him that there are 5 people who want to murder her. Soon after she falls overboard, and though she is rescued, Jocko is accused of pushing her. This leverage ends up enough to force him to accompany her to the Long Island home of a rich old man, Luther Bell, along with a few other people from the ship.

Over the next couple of days Jocko learns a bit more of Jocelyn's unfortunate history. She is given an overdose of drugs, and one of the other men flees, perhaps incriminating himself. In something like desperation, Jocko decides to marry Jocelyn, as much because she insists he's the only man who truly cares for her, essentially making him feel guilty -- he half or more suspects that both the overdose and the plunge into the ocean were suicide attempts. But there are more and more secrets in Jocelyn's life, and concerning her history with the various residents of the Bell household as well as the visitors from the ship. Can Jocko escape her clutches -- or instead can he rescue her from her sordid past?

As I said above, my main problem with this book is that Jocko's motivations and thoughts just didn't seem real to me. Jocelyn's story is interesting and sad, but a bit fuzzed out, held too much at a distance. The novel is interesting and strange but on the whole it seemed too artificial a construct to me.

Thursday, June 12, 2014

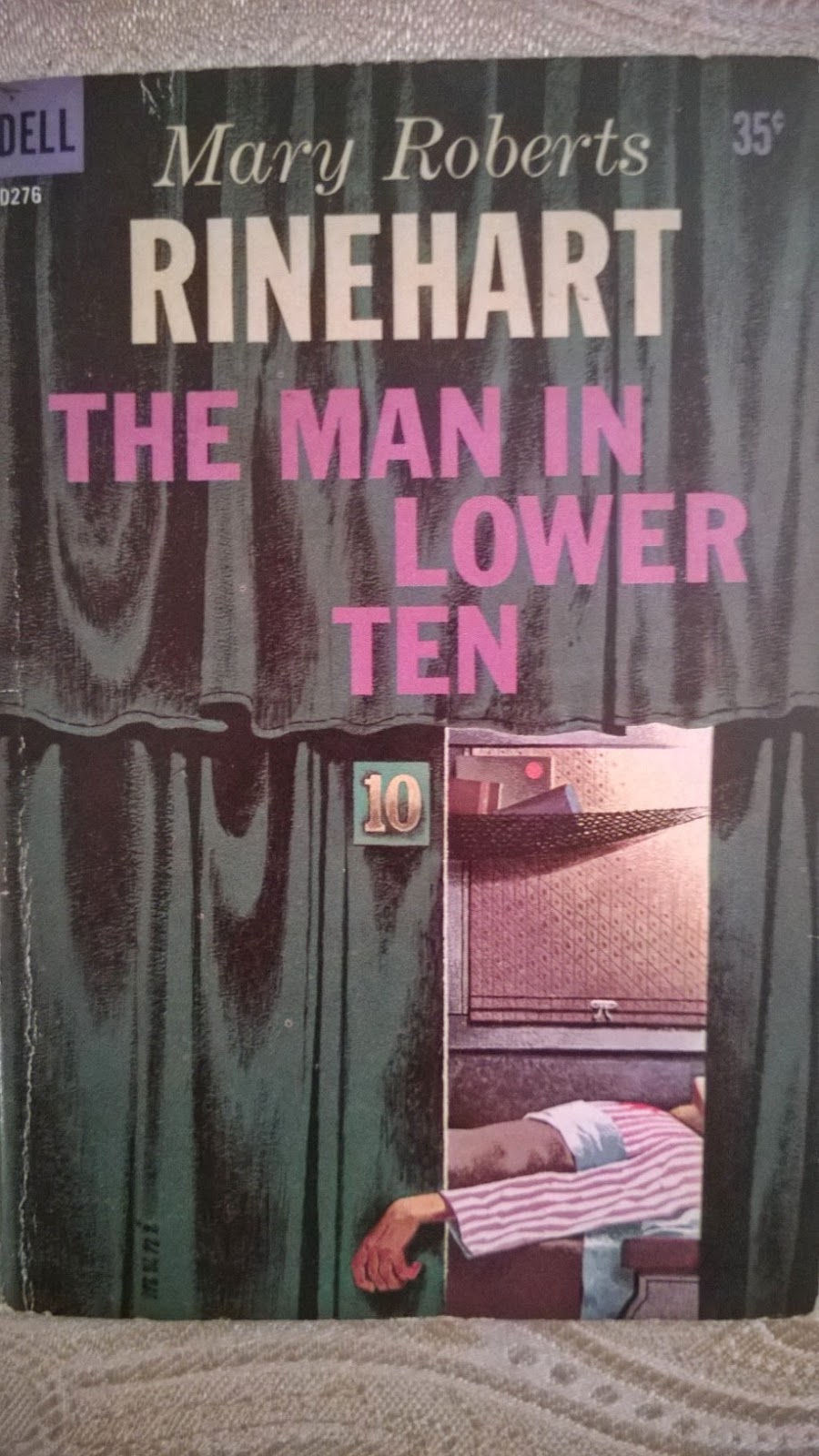

Old Bestsellers: The Man in Lower Ten, by Mary Roberts Rinehart

The Man in Lower Ten, by Mary Roberts Rinehart

a review by Rich Horton

Mary Roberts Rinehart (1876-1958) was a very popular mystery/suspense writer in her time, and her fame, while slowly dwindling, seems to me, has not disappeared. I certainly was aware of her in the '70s when I was reading Agatha Christie and the like. I confess I'd have guessed she was closer to a contemporary of Christie's, and that she was still alive in the '70s. (For that matter, I sometimes have confused her with Mary Higgins Clark.) Rinehart was often called "the American Christie", but that was really unfair to her, as she started 15 years or so before Christie (who was 12 years her junior) and was quite popular well before Christie even began writing.

Rinehart was born in (what is now) Pittsburgh, trained to be a nurse, and married a doctor, Stanley Rinehart. She began publishing stories in the downmarket magazines of the time in 1904, to help her family's finances after the stock market crash of 1903. Her first novel was the one covered here, The Man in Lower Ten, which was serialized in All-Story Magazine in 1906. (Her second novel, The Circular Staircase (1907) is often sloppily called her first, as it was the first to become a book.) The Man in Lower Ten was published in book form in 1909, and it was the fourth bestselling novel of that year according to Publishers' Weekly. It is considered the first novel clearly in the mystery genre to become a general fiction bestseller. My copy is a 1959 Dell paperback, complete with interior illustrations.

A bit later I ran across an early hardcover reprint as well -- I had hoped on first seeing it that it might be a first edition, but instead it's a Grosset and Dunlap reprint from perhaps 1913. It is also illustrated, by Howard Chandler Christy. I've reproduced (in photographs by my son Geoff) the cover, and title page with frontispiece, below:

Rinehart diversified somewhat in later years, writing Broadway comedies, nurse fiction, and mainstream novels. (The latter apparently at the urging of her husband, who seems to have been a bit ashamed of her reputation as a trashy genre writer. He also apparently eventually resented the fact that she made much more money than he did.) By the end though she returned most often to mystery/suspense stories, and those are by far her best remembered works. I can recommend an excellent website by Michael Grost (mikegrost.com/rinehart.htm) for a detailed analysis of her career.

One tidbit about Rinehart that is often repeated is that she originated the phrase "The butler did it". This is untrue, though in one of her better known novels the butler is indeed the murderer. But there were novels and stories in which the butler was the murderer before that, and she never used that exact phrase.

According to Grost, her first two novels, The Man in Lower Ten and The Circular Staircase, may be her best. I can't comment -- The Man in Lower Ten is the only novel of hers I've read. But it is pretty decent work.

Lawrence Blakely is a Washington, DC, lawyer. His partner, Richey McKnight, inveigles him into taking a trip to Pittsburgh to take a deposition from a rich old man in a forgery case. It seems McKnight has a date with a girlfriend. Girls are famously of no particular interest to Blakeley ...

On the way back from Pittsburgh, strange things happen. There is repeated confusion over which bunk Blakely has engaged. There are a couple of interesting seeming people on the train. Blakely ends up forced into another bunk by a drunk passenger, and when he wakes up, his bag -- with the critical deposition -- and also his clothes are gone. He is forced to dress in another man's clothes, and in searching for his bag he discovers a murdered man.

Almost immediately Blakely is the prime suspect -- but before anything further happens the train crashes. Blakely is thrown free, and indeed is one of only four survivors, sustaining only a broken arm. He and another survivor, a beautiful young woman, Alison West, escape to a farmhouse where something unusual happens that Blakely doesn't understand for some time. He does realize, however, that a) Alison West is the granddaughter of the rich old man from whom he took the deposition; b) she is another prime suspect in the murder; and c) he is in love with her.

Blakely returns to DC but soon his troubles multiply. The police are lurking around his house. Another survivor from the wreck fancies himself an amateur detective and insists on investigating the otherwise almost moot murder case (after all, the witnesses are mostly dead and the victim could have been written off as merely another casualty of the train crash). Someone seems to be lurking in the house next door. And, finally, it seems that Alison West is the girl whom his partner McKnight has been seeing.

The shape of the resolution is not surprising, and indeed the solution to the primary crime, while not ridiculous, does seem a bit strained. But the novel bounces along nicely enough. Lawrence Blakely is not exactly a convincing three-dimensional character, but he's still kind of intriguing, and his voice, as teller of the story, is effective. Rinehart's writing is not brilliant, but it's solid storytelling prose, with some good turns of phrase. She does slip once or twice (for example, Blakely's arm heals for a brief passage before returning to its broken state), but really it's a solid professional effort. I liked it, though I have to say, not enough to make a special effort to seek out more of Rinehart's work.

Thursday, June 5, 2014

Old Bestsellers: The King's Jackal, by Richard Harding Davis

The King's Jackal, by Richard Harding Davis

The King's Jackal, by Richard Harding Davisa review by Rich Horton

Richard Harding Davis (1864-1916) was the son of Rebecca Harding Davis, a fairly well-known and significant writer in her day. His father was a journalist, editor of the Philadelphia Public Ledger. So perhaps it's not a surprise that Richard became a very famous journalist and novelist. He was something of a football star in his abbreviated college days (this would have been very early indeed in the history of American football). After being invited to leave two colleges (Lehigh and Johns Hopkins) he became a journalist, gaining a reputation for a flamboyant style and for tackling controversial subjects. (All this from Wikipedia.)

He became a leading war correspondent, and was particularly noted for helping to create the legend of Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders, and also for his reports on the Boer War. He was also strikingly good looking (so I judge from the picture on his Wikipedia page), and was credited for popularizing the clean-shaven look, and as the model for the the "Gibson Man", the analog to his friend Charles Dana Gibson's "Gibson Girl".

Davis was likely better known then, and is still more remembered, for his journalism, but he wrote quite a lot of fiction as well, much of it very successful. (To be sure, there are those who would suggest that some of his journalism was fiction as well!) The only book of his I can find on the Publishers' Weekly fiction bestseller lists (the top ten of each year) is Soldiers of Fortune, the #3 bestseller of 1897. But the book I have is from 1903, The King's Jackal, which comprises two novellas, "The King's Jackal" (30,000 words) and "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" (17000 words). The publication history is a bit complicated, and worth addressing as it hints at some of the publishing world of that time. "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" was written in 1891, and sold to the McClure syndicate for serialization -- presumably it appeared in various newspapers (the Boston Globe being one of them). That same year it was published in a collection, Stories For Boys (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1891); and again in 1896 in another collection, Cinderella and Other Stories. (At a guess, the latter book was considered for adults, while Stories for Boys was marketed for children, so "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" was being repositioned as an adult story (which it surely is) in the second collection.) "The King's Jackal" was serialized in Scribner's Monthly in 4 parts, April 1898 through July 1898. A book edition came out from Scribner's that same year. Finally, in 1903, "The King's Jackal" and "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" were reissued together as The King's Jackal, also from Scribner's. The copyright page for that book, which is the one I have, duly reports "Copyright 1891, 1896, 1898, 1903".

(Let me add thanks to the help of Endre Zsoldos, Denny Lien, Richard Fidczuk, and the excellent resource unz.org in clarifying this complex publication history.)

Todd Mason noted of a couple of previous books I reviewed in this series that the covers appeared to be Gibson Girl covers. (I don't know if those covers were actually by Gibson or derivative of him (or even of someone else like Harrison Fisher).) (Indeed, I saw a copy of Harrison Fisher's American Beauties (1909) at an antique mall in St. Joseph, MO, this past weekend, and Fisher strikes me as wholly as important as Gibson in promulgating a turn of the century image of American women.) The King's Jackal truly is illustrated by Charles Dana Gibson. My copy doesn't have a dust jacket, but I've turned up a couple of images of the original dust jacket and it is indeed by Gibson (a reproduction of the frontispiece art from my edition). Above I show (somewhat pointlessly) a picture of the cover of my edition (which is just the Charles Scribner's Sons monogram, really), plus pictures of the title page and frontispiece.

"The King's Jackal" is about the exiled King of Messina. Messina of course is a major city on Sicily. In this novel, it is said that the Republican movement in Italy kicked the King out, and also made the Catholic Church illegal. I don't know if this corresponds very closely to history. It doesn't seem to jibe exactly with the events portrayed in one of my favorite novels, Giuseppe di Lampedusa's The Leopard (one of the greatest novels of the 20th Century in my opinion), which is about a Duke in Sicily at the time of the Risorgimento.

Anyway, the King is actually fairly happy to be exiled. He didn't care for the burdens of actually ruling his people, nor did he care for his home. He spends his time in Paris and Tangier and such places, with his mistress and a few fellow exiles. He's a thoroughly nasty man, corrupt, a sexual predator, lazy. He's also running out of money, so he has hatched a scheme to raise a lot of money from loyalist families and from monarchists in general, and to stage a fake invasion of Messina which will fail. Then he'll keep the rest of the money.

The only problem is that a couple of his associates are true believers. These include the title character, Prince Kalonay, called "The King's Jackal" because out of misplaced loyalty to the King he has assisted cynically in his debaucheries. But he has been "saved", as it were, by Father Paul, a monk who is wholly devoted to restoring the Church to Messina. The King is worried that Prince Kalonay and Father Paul, in leading the expedition to Messina, might actually succeed -- so he has had his mistress betray the plans to the General of the Republican forces.

A further complication is Patty Carson, a beautiful young American woman, a devout Catholic, who has pledged a great sum of money to Father Paul to restore the Church. The King's problem is twofold -- one, to keep Patty from figuring out the deception, and, two, to try to get his hands on the money, which she would prefer go straight to Father Paul.

Perhaps predictably, Patty Carson and the Prince Kalonay fall rapidly in love (without revealing their feelings to each other). Kalonay, in particular, considers himself unworthy, due to his previous corrupt ways -- but perhaps if he is successful in his expedition to Messina, he will have restored his honor sufficiently. (The King, meanwhile, considers raping Patty Carson as part of the project, and also because he seems to regard it as sort of his droit de seigneur. He really is a nasty man.) Meanwhile, an heroic American reporter shows up to cause further problems for the King. This is Archie Gordon (who, one thinks, might be modeled in the author's mind on himself), who inconveniently is well acquainted with Miss Carson. Gordon is horrified that Patty is involved with a group of people he knows to be reprobates ... and then he runs into a spy for the Republican side of Messina ... Will he queer the whole pitch by finding out the real plans of the King? Or can Patty convince him to support her goals? Or ...

It ends more or less as one might expect, though curiously (and, I think, correctly), at the psychological climax -- we are never to know how things really turn out, but we do know how Prince Kalonay and Patty Carson and even Archie Gordon are changed, and what they plan to do. Not great stuff but fairly enjoyable in its way.

"The Reporter Who Made Himself King" is cynical as well, but in a different and much more comical way. The protagonist is another journalist named A. Gordon -- A for Albert in this case. He's a young pup just out of college, and desperate to find a war to cover, but there are no wars on the horizon. So he decides to write a novel instead, and jumps at the chance to serve as secretary for the newly appointed American Consul to the remote and tiny Pacific island Opeki. On arriving at the beachfront village where lives the tribe with whom the US apparently has established tenuous relations, the Consul immediately quits, leaving the job to Albert. His only assistants are a very young telegraph operator for a nearly defunct telegraph company, and two British seamen, deserters. Soon he realizes that war threatens, in the form of another tribe, which lives in the interior hills of the island and periodically raids the coastal tribe.

Albert convinces the local King to start an army for defense purposes, but when the hill tribe invades, things don't go quite as planned, mainly because a German ship has shown up with the intention of planting their flag on the island, and they have negotiated with the hill tribe. Albert manages to convince the Kings of both tribes that that isn't a good solution, and he gets them, implausibly, to agree to make him King temporarily. And then he manages, more or less, by accident, to provoke a hostile response from the Germans. Which would be no big deal, except the telegraph company, on receiving Albert's report (his first war correspondence!) decides to rather exaggerate what happened, risking starting a war between the US and Germany.

Again the story ends more or less at the climax -- when we realize exactly what sort of fix the characters have got into, but not how things will end. Which works out fine in this case as well. Here Davis' intent is more purely comical, along with a fair amount of satirical comment on the influence of the news media on national relations, and their culpability in fanning the flames of war (something Davis himself was accused of later). Again, not a bad story, fairly funny at times. (And, I must add somewhat obviously, somewhat racist in its depiction of the natives, though perhaps this is blunted a bit because none of this is really intended to be taken at all seriously.)