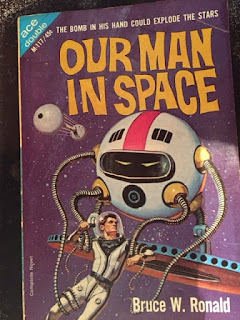

Ace Double Reviews, 92: Our Man in Space, by Bruce W. Ronald/Ultimatum in 2050 A. D., by Jack Sharkey (#M-117, 1965, 45 cents)

Ace Double Reviews, 92: Our Man in Space, by Bruce W. Ronald/Ultimatum in 2050 A. D., by Jack Sharkey (#M-117, 1965, 45 cents)a review by Rich Horton

Ace Doubles again. Most of the previous Ace Double reviews I've done feature books I've chosen because I had at least some interest in one of the writers. This one was a lot more random -- basically, it was inexpensive and it was available at a dealer's table at a recent convention (can't remember which -- Sasquan, Archon, or Windycon). I had never heard of Bruce Ronald, and while I know Jack Sharkey's name well, from any number of stories in early 60s magazines, he's never been a particular favorite of mine. I actually have another (the only other) Sharkey novel, The Secret Martians, as part of an Ace Double I bought for a more usual reason: the other side is by one of my favorites, John Brunner. I'll get around to reviewing it eventually.

Bruce W. Ronald was an advertising man, born in 1931 in Dublin, Ohio, and still alive as far as I (or the Science Fiction Encylopedia) know. He published only this one novel, and no further stories; but he did write the book for a musical, in collaboration with Claire Strauch and the well-known SF/historical writer John Jakes. This was Dracula Baby!, in 1970. (The SFE says that Ronald was also an actor.)

So it turns out Jack Sharkey had another slight connection with Bruce Ronald: he became a playwright and one of his plays was called Dracula, the Musical?, which on the face of it sounds like it might resemble Dracula Baby! in more ways than having an unexpected punctuation mark at the end of the title. Sharkey wrote four short novels, three of them (including Ultimatum in 2050 A. D.) serialized in Cele Goldsmith's magazines, Amazing/Fantastic. He published about 60 stories in the field, almost all between 1959 and 1965. It may be that Goldsmith/Lalli's departure as editor influenced Sharkey's decision to switch fields -- she bought the great bulk of his stories. (She published no fewer than a dozen of his stories in 1959 alone!) His most famous story might be "Multum in Parvo", from Gent in 1959, and reprinted in Judith Merril's Fifth Annual Year's Best SF. He also wrote an Addams Family tie-in novel.

So it turns out Jack Sharkey had another slight connection with Bruce Ronald: he became a playwright and one of his plays was called Dracula, the Musical?, which on the face of it sounds like it might resemble Dracula Baby! in more ways than having an unexpected punctuation mark at the end of the title. Sharkey wrote four short novels, three of them (including Ultimatum in 2050 A. D.) serialized in Cele Goldsmith's magazines, Amazing/Fantastic. He published about 60 stories in the field, almost all between 1959 and 1965. It may be that Goldsmith/Lalli's departure as editor influenced Sharkey's decision to switch fields -- she bought the great bulk of his stories. (She published no fewer than a dozen of his stories in 1959 alone!) His most famous story might be "Multum in Parvo", from Gent in 1959, and reprinted in Judith Merril's Fifth Annual Year's Best SF. He also wrote an Addams Family tie-in novel.Our Man in Space is a very minor work of SF, but for much of its length it's amusing enough, before a somewhat too extended ending. It's about an actor, Bill Brown, who is hired as a spy for Earth, because of his acting skill and his resemblance to an Earth diplomat, Harry Gordon, who has been killed. Brown's job is to impersonate Gordon, and to travel to Troll, where Harry Gordon has been hired by the officials of Troll to find out when overpopulation pressures will cause Earth to explode. It seems that the Council of 16, a group of local planets, has refused new Galactic member Earth the right to colonize any planets.

Brown goes to Troll, on the way meeting a beautiful Galactic woman. (It seems that most of the planets in the Council of 16 have nearly fully human residents -- certainly sex is possible between these species.) On Troll he manages to complete his assignment, and also to make time with the beautiful Galactic, who eventually dumps him ... and Bill finds out as well that his superiors have betrayed him, and he will be killed. He escapes and kills a few Trollians, before sneaking onto a spaceship and heading for Grendid, a monarchy that it turns out is the leader of the aliens who are voting against Earth's pleas for colonization rights. On Grendid he again eludes attempts on his life, and again makes time with beautiful aliens, including a spy from a Matriarchy world, and against all odds he finds a way to save the King of Grendid from an assassination attempt, which should improve Earth's odds in the upcoming vote. But then we witness the Council of 16's deliberations, and more treachery is in store, from multiple planets, and it's up to Bill Brown to implausibly save the day again. And by the way meet up again with the first beautiful Galactic woman, for a passionate but all too brief reunion.

OK, this is really silly stuff. It doesn't make sense on any level at all -- scientific, political, plot plausibility, sociology, characterization. But it isn't really trying, and for a while it's pretty good fun, though it does wear out its welcome rather. (There are a few seeming nods to Heinlein -- the basic plot bears some points of resemblance with Double Star, and one character is called the local "Citizen of the Galaxy", and a character reminded me just slightly of Star, Empress of the Twenty Worlds ...)

As for Ultimatum in 2050 A.D., in the end it may be even sillier. It was first published in Amazing, in the June and July 1963 issues, under the title The Programmed People. Surprisingly, it has been reprinted recently, in 2010, as part of a Double Novel from an outfit called Armchair Fiction. (The other novel is Slaves of the Crystal Brain, by "William Carter Sawtelle" (a pseudonym for Roger Phillips Graham, who usually published as Rog Phillips).) The Armchair Fiction Double Novels seem to consciously imitate Ace Doubles (for example, with a similar color scheme), and also to concentrate on works at the pulpier end of the spectrum. The cover art for the Armchair Fiction edition of The Programmed People is the same as used for the June 1963 Amazing, by Ed Emshwiller, and not to my mind one of his better efforts. (Belatedly, I'll add that the covers for the Ace Double at hand are by John Schoenherr (for the Sharkey novel) and Ed Valigursky (for the Ronald novel).)

Anyway, Ultimatum in 2050 A. D. is set in the title year in "the Hive", a sort of arcology, a huge building in which 10,000,000 people live. Life is apparently good there, except for the strict rules about "readjustment", whereby one can be sent to the hospital for such things as voting the wrong way, not voting at all, or minor injuries. Lloyd Bodger is a normal young man, engaged to Grace Horton (nice name that!), occasionally in trouble for missing a vote or two ... despite being the son of the Secondary Speakster, the number two man of the Hive. One night he almost misses a vote, until a girl gives him her place in line. Shortly later it becomes clear that the girl is wanted for treason ... and against his better instincts, Lloyd decides to help her. Before long he finds himself embroiled in a resistance movement against the rulers of the Hive ... the girl, Andra, and her fellow conspirators Bob Lennick and Frank Shawn, make such crazy claims as that "Readjustment" simply means incineration -- to keep the population at the maximum 10,000,000.

So it goes for the first half of the book -- some frantic running around as Lloyd and Andra and the unwillingly roped in Grace try to avoid detection by Lloyd's father and his boss, the Prime Speakster Fredric Stanton. There is some treachery, some narrow escapes, and some loopy but almost fun ideas like the "Goons", robots that enforce the Hive's rules, and "Ultrablack", a scientifically implausible induced absolute darkness. There's a bit of sexual tension -- Andra seems a real potential rival for Grace, who loves Lloyd but who Lloyd seems unsatisfied with.

Then I think Sharkey got bored, or wrote himself into a corner, or something. The second half of the novel begins with a long piece of pure exposition, explaining in the most politically and scientifically absurd ways how the election of 1972 (only a decade or so after the novel was written!) led swiftly to the creation of the Hive, and to the establishment of it quasi-religious ruling structure and strict rules. After that there is the denouement, which never surprises except by the silliness of the action and resolution. I won't give away what happens, though, as I said, it's not really surprising at all. In the end quite a weak story.