The Man from Scotland Yard, by David Frome

The Man from Scotland Yard, by David Fromea review by Rich Horton

This book might not have been a real bestseller but it seemed to do OK: the edition I have was the fifth printing (in about a year) of the Pocket Books edition. Indeed, its publication history is interesting (to me), and a bit of a window on publishing history in general.

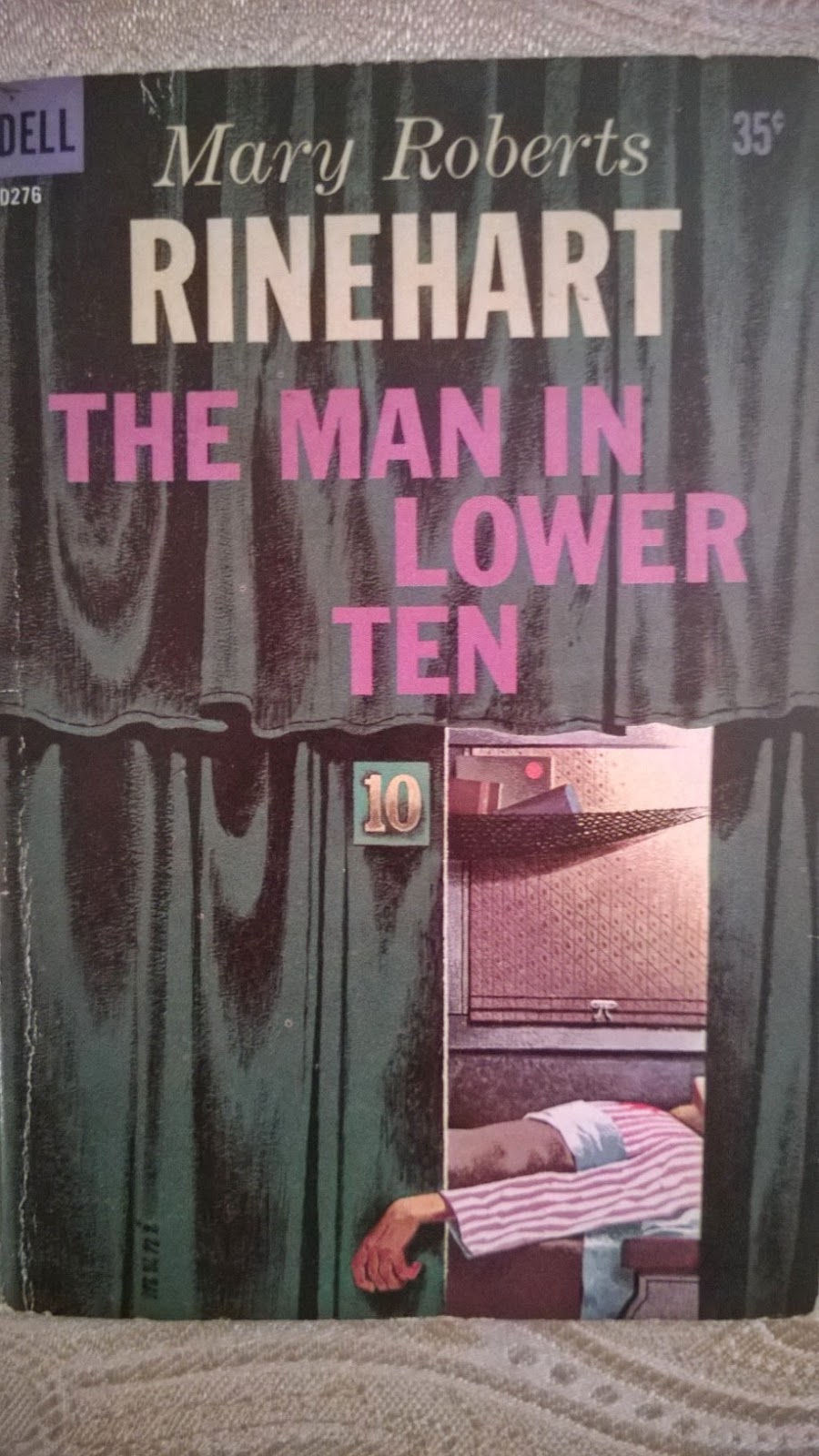

The first edition, in 1932 was from Farrar and Rinehart. This company was founded in 1929 by John C. Farrar and Stanley Rinehart, Jr. This was the first of two prominent publishing firms founded by Farrar -- the second of course is the legendary Farrar, Straus and Giroux, founded as Farrar, Straus in 1946. Stanley Rinehart was the son of famous mystery writer Mary Roberts Rinehart. He and his brother Frederick had worked at the firm George H. Doran (which published the last book I reviewed, You Know Me Al, by Ring Lardner), but which became Doubleday, Doran after a merger in 1927. Stanley and Frederick then joined Farrar in his new venture, taking their mother and her future books with them. After Farrar left Farrar and Rinehart, the company was called Rinehart and Company until 1960, when a merger with two other companies, Henry Holt and John C. Winston, created the prominent firm Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

There were no mass market paperbacks in the early '30s, so the first inexpensive edition of The Man from Scotland Yard was a hardcover from Grosset and Dunlap in 1934, one of the (perhaps THE) leading reprint hardcover houses. The mass market paperback was essentially invented by Pocket Books in 1939, so this book, first reprinted in paperback in 1942, was a fairly early example. And my edition, I should add, was a wartime edition, and the publishers made special note of that, with this disclaimer: "In order to cooperate with the government's war effort, this book has been made in strict conformity with WPB regulations concerning the use of certain materials." There is also a sort of PSA at the end urging people to "HELP WIN THE WAR! Don't waste anything."

As for the author, "David Frome" has a somewhat interesting history. Frome was a pseudonym for an American writer with the unlikely name of Zenith Brown (nee Jones). Zenith Brown was born in California (daughter of a missionary to Indians), and was educated at the University of Washington (in Seattle), and briefly taught there, but lived much of her life in Annapolis. Her husband, Ford K. Brown, was a Professor at the very well regarded liberal arts school St. John's College in Annapolis: known primarily for their "Great Books" curriculum. Zenith Brown (1898-1983) published her first novel in 1929, when she was living in London: In at the Death, as by Frome. Her English-set books continued to be published under the Frome name, but she also wrote a great many mysteries set in the US (mainly in the DC area) as by "Leslie Ford", and also a few books as by "Brenda Conrad". As "Leslie Ford" she was apparently a regular in the Saturday Evening Post. She stopped writing )or at least publishing) in 1962.

Well, after all that blather, what was the book like? I quite enjoyed it. It's billed as "A Mr. Pinkerton Mystery", as were most or all of her British-set books. Mr. Pinkerton is a mousy Welsh widower, free at last from the domination of his horrible wife, but with nothing in his life except his (apparently accidental) friendship with Inspector J. Humphrey Bull of Scotland Yard. Pinkerton is not really central to the book, though he's an important character. The story is told from multiple points of view, but Bull's POV is most important.

It opens with a pair of young men noticing an acquaintance of theirs, the somewhat older (but still beautiful) Diana Barrett, looking distressed and heading to a moneylenders'. It seems she is known as a reckless gambler on horse racing. And indeed Mrs. Barrett is next seen begging Mr. David Craikie for extra time to pay back her £5000 loan. But it seems she must ask David's brother Simon instead, and he is not in. Then we meet handwriting expert Mr. Arthurington, returning from holiday in France. When Mr. Arthurington gets home, he is shocked to discover a dead man in his house, which had been rented but (mysteriously?) vacated a short time previously. Next up is Inspector Bull, looking into the matter of an odd note claiming "a mother and three little ones" have been killed and buried in the back garden of a small house ... only to find that the murdered creatures are cats. And finally we meet Mr. Arthurington's daughter Joan and her friend Nancy, also returning to England in the company of their duenna, Miss Mandle.

All this seems terribly complicated, and it is. Before long another murder has occurred, and Inspector Bull is on the case, soon realizing that -- perhaps -- the two murdered men are in fact the moneylenders Simon and David Craikie. Or are they? The two brothers were reclusive people, and the identification doesn't seem absolutely certain. Mr. Pinkerton shows up begging to help, and to get him out of his hair Bull asks him to investigate the matter of the murdered cats ... and somehow Pinkerton, largely by accident, finds out, or helps Bull find out, and unexpected connection between that disquieting but trivial incident and the double murder. As for all the other characters ... Mrs. Barrett, the Arhuringtons, even the two young men in the opening scene ... they are all connected to each other -- mostly they are neighbors, and indeed they also have at least slight connections to the Craikies, or to the Craikies' lawyer.

Complications build on complications. There is a Craikie sister and a (missing) Craikie daughter. The Australian tenant of the Arthurington house might be implicated. Social climbing Americans are mentioned. Mr. Arthurington's handwriting expertise comes into play. And Mr. Pinkerton goes off to Liverpool ...

The whole construction is highly improbable and overcomplicated, but it does pretty much hold together, and it makes for a satisfyingly intricate mystery with a fairly believable solution (believable under the implicit conditions of this subgenre). Inspector Bull is an pretty well-realized, if somewhat stock, character, and enjoyable to read about. There are moments of suspense and danger, and the book is always readable and interesting. It's far from a great work -- it's an artificial construction. But on its own terms it's quite fun. Edmund Wilson (not a favorite of mine ... wrong about Lovecraft, wrong about Tolkien, wrong about entertainment in general -- though to be fair, pretty much right about the likes of Nabokov and Hemingway and Fitzgerald) famously asked "Who cares who killed Roger Ackroyd?", and of course that's a classic case of entirely missing the point. No, we don't really "care" about Ackroyd -- or, in this book, the Craikies -- in any deep way: the pleasures are different and doubtless shallower, but this sort of book does what it does (when done well) effectively.