Neal Stephenson was born on my first Halloween -- October 31, 1959, when I was all of 26 days old. In honor of his birthday, then, here are two reviews I did long ago, of his novels Quicksilver and Cryptonomicon.

First, Quicksilver:

Review Date: 12 April 2004

Quicksilver, by Neal Stephenson

William Morrow, New York, NY, 2003, 927 pages, Hardcover, US$27.95, ISBN:0-380-97742-7

a review by Rich Horton

What to say about Neal Stephenson's Quicksilver (first of The Baroque Trilogy) that has not already been said? It is largely as has been reported: overlong, rambling, annoying anachronistic, not terribly well plotted. Yet for all that I rather liked it. I certainly didn't love it, and it is by no means as good as Cryptonomicon or Snow Crash, but it is a generally enjoyable and interesting hodgepodge of political intrigue, early scientific inquiry, disease and grime, and eccentricity. For a negative review with which I almost entirely agree in specifics, I suggest Adam Roberts's. All I can say is that I have little objection to Roberts's arguments, but that I came away from the book having enjoyed myself.

The story is told in three long books. (The entire novel is some 380,000 words, so each book is a substantial novel-length in itself. And of course Quicksilver is only the first of a trilogy!) The first book is about Daniel Waterhouse and his relationship with Isaac Newton. Waterhouse is one of a prominent Puritan family, who have wielded some influence during Cromwell's Protectorship. But the story really takes place as Waterhouse goes up to Cambridge, just after the Restoration of the Monarchy. Daniel's loyalties are divided -- he is still his father's son, but hardly a true believer in the Puritan religious doctrines. At Cambridge he befriends the very strange and otherworldly Isaac Newton. Daniel himself is presented as a competent natural philosopher but nothing special -- he is there as a witness to genius embodied by Newton (and others such as Hooke, Huygens, and Leibniz). Daniel becomes a minor political player, Secretary of the Royal Society, sort of a tame Puritan in the Royal cabinet. This section is told on two timelines -- one following Daniel from youth to near middle-age, the other a rather pointless account of Daniel beginning a much later (1714) journey back from Massachusetts (where he seems to have founded MIT) to London in order to testify in a dispute between Newton and Leibniz about the invention of the calculus. This last thread is, I think, a complete mistake -- it does absolutely nothing for the current book. I am sure it will be picked up in later books, and probably be important, but it's just so many wasted pages here.

The second book abandons Daniel entirely to tell the story of two rather lower-class individuals. Jack Shaftoe (the names Shaftoe and Waterhouse will of course be familiar to readers of Cryptonomicon) is a Vagabond -- at first an orphaned boy making a living by jumping on the legs of hanged men to hasten their death and reduce their agony, later a rather lazy mercenary fighting in various wars on the continent. He comes to Vienna, under siege by the Ottomans, and by happenstance manages to rescue a beautiful virgin named Eliza, a native of Qwlghm (a fictional island off the coast of England also from Cryptonomicon). Eliza had been kidnapped from the shores of Qwlghm and sold to the Ottoman Sultan, who fortunately was preserving her to be a gift to one of his generals after the presumed success of the Vienna campaign. Eliza's experience has given her one consuming passion -- the eradication of slavery. Jack (who is nicknamed Half-Cocked Jack due to an unfortunate earlier surgical procedure -- hence Eliza's virginity is safe from him -- though they find other ways to have a good time) and Eliza wander back across Europe to the Netherlands, meeting Leibniz along the way and having a variety of adventures. Finally Eliza is established in Amsterdam, becoming a financial genius and a spy for William of Orange, while Jack makes his way to Paris and eventually to a seat as a galley slave.

The third book switches between Eliza and Daniel, and in this book there is a somewhat coherent plot. Basically, by now the book becomes the story (told from an unusual angle) of England's Glorious Revolution, when William of Orange and his wife Mary take the crown of England from the hated Catholic James II. Eliza's role takes her to Versailles where we see the court of the Sun King, while Daniel plots against James from within his cabinet. The book ends more or less with the successful conclusion of the Glorious Revolution.

As I say above -- there is much wrong with this book. It is too long. Though I was never precisely bored I was often not particularly concerned as to when I would next pick up the book. (It took me the entire month of March to read it.) It is full of very jarring anachronisms, mostly in the speech of the characters. (The events and devices described are as far as I know all essentially real, except for the irruptions of the long-lived alchemist Enoch Root.) Stephenson has defended this by claiming the book is written for 21st Century readers -- if so, then why the absurd spelling tics, such as phanatique for fanatic? In the end the anachronisms simply annoyed me, pulled me out of the book. The overall plot, to the extent I could detect one, is hardly advanced at all in this book, though I think an argument can be made that there is a significant plot thread (taking us from the Restoration to the Glorious Revolution) that is resolved in this book and works fairly well. The characters are to some extent grotesques but mostly interesting grotesques -- they are, I suppose, the main reason I ended up liking the book on balance.

(And all that said, for a book set in the same time period, I recommend much more highly William Makepeace Thackeray's Henry Esmond.)

Second, Cryptonomicon:

Neal Stephenson's Cryptonomicon is a huge book (about 425000 words). It's not really SF, though it hovers on the edge of being SF. It's a very absorbing book, and a fascinating book. Also, its strengths are those that lend themselves to a long novel: it is continually interesting, on the one hand; and on the other hand the plot is a minor source of the interest. Thus there aren't boring parts that you have to wade through to get to the end: and getting to the end isn't as much the "goal".

It's told on two timelines. One is set during World War II. Two main characters are followed in this thread: Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse, a math genius and friend of Alan Turing who ends up assigned to the joint US/British codebreaking effort; and Bobby Shaftoe, a Marine who ends up assigned to a unit Waterhouse deems necessary: a unit which will fake evidence that the Allies had other means than codebreaking to allow them to achieve some of the successes they really achieved because they could read the Axis codes. Thus the Germans and Japanese hopefully won't change their codes. For some time this thread deals with the codebreaking end of things, but after a while interest begins to focus on a scheme by the Germans and Japanese to hide a bunch of gold in secure caches in the Philippines and elsewhere. This introduces a couple more viewpoint characters: Japanese engineer Goto Dengo, German U boat captain Gunter Bischoff, and another member of Bobby Shaftoe's special unit, the Australian priest Enoch Root.

The other thread is present-day. Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse' grandson, Randy Waterhouse, is part of a startup company trying to establish a "data haven" in a small island country in the Pacific. This work takes him to Manila, where he meets Bobby Shaftoe's granddaughter, America (Amy) Shaftoe. (Neither Bobby Shaftoe or Lawrence Waterhouse ever revealed to their children what they did during the War, so Randy and Amy have no idea that their grandfathers knew each other.) Randy's efforts brush him against some organized criminals. Also, they find something interesting in Manila Bay while laying cable, something which Randy recognizes as having to do with his grandfather. Soon he is involved in a race to find one of the caches of Axis gold, and his success may depend on breaking a code his grandfather couldn't break.

All this is a fairly fascinating story by itself, with lots of action and heroism, but what makes the book really work is the clever stuff Stephenson does with infodumps. He tells us about Unix systems, cryptanalysis, eating Cap'n Crunch properly, proper computer security, mining engineering, cannibals on New Guinea, Douglas MacArthur's relationship with the Marines, computer games, Japanese atrocities during the War, and much more. And he's a very funny writer as well. For example, he has an extended joke about an obscure (i.e., nonexistent in our history) set of islands belonging to the UK, with a language all their own, such that, for instance, Smith is spelled cCmmcdn, or something. Of course this is relevant to cryptography. But it's also very funny. The characters are involving, if perhaps just a bit on the bestsellerish side: that is, they are a bit on the supercompetent side (though also with real weaknesses). I really really enjoyed this book. I'm not sure whether to nominate it for a Hugo, though: it's definitely one of the 5 best books I've read from 1999, but is it close enough to SF?

Wednesday, October 31, 2018

Monday, October 29, 2018

Birthday Review: The Lights in the Sky Are Stars, by Fredric Brown

Birthday Review: The Lights in the Sky Are Stars, by Fredric Brown

a review by Rich Horton

Today would have been Fredric Brown's 112th birthday. In his honor, then, I decided to post a fairly brief review I did a long time ago, for my SFF Net newsgroup, of his novel The Lights in the Sky Are Stars.

Brown (1906-1972) was a well-respected writer in both the SF and Mystery genres, winning one Edgar for his novel The Fabulous Clipjoint. His work was often funny, though often with a serious, even dark, undertone. He was well-known for his very short stories. His best known short story is probably "Arena", which was anthologized in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, and which is considered a source for the Star Trek episode of the same title. Here's what I wrote back in 1999 (which is also when the novel is set):

I read an old SF novel I'd been meaning to try for some time, Fredric Brown's The Lights in the Sky Are Stars (1953). This tells of a spacestruck man in 1999, an aging spaceship mechanic, who becomes involved with a politician and her efforts to reignite America's space program by pushing for the development of a ship to Jupiter. It's mostly too cheesy and melodramatic to work: we need to put up with the hero breaking into an opposing politician's office to steal the meticulous records detailing his corruption, for instance, and with a tragic death, caused because a ten-day delay in getting the program started was impossible, and with the hero teaching himself spaceship administration in no time, and cutting the cost of the program from a near-prohibitive 300 million dollars (!) to 26 million dollars. Among other things. At the end there is another weird twist, almost the most melodramatic of all, which oddly almost works, and allows the novel to close on an effective, quite moving note. It's still a case of preaching to the choir, though. And in the final analysis I felt the cheesiness and implausibility of most of the novel doomed it.

By the by there are some neatly typical '50s predictions for 1999: TV remote controls, but those fixed to the living room chairs (!), private helicopters as a common means of travel, and chemical rockets planned to reach the moon by 1969. (But they switched to atomics and got there by 1965: too bad for Brown's prediction record.) There's also the odd '50s faith in progress uber alles: the lead character refuses to believe that light speed is a real limit (humanity's beat every other limit it's faced, by gum, it won't let a little thing like the special relativity stop it!), though to be fair that's only his attitude: the novel itself has no relativity-beating. And there is a curious, somewhat effective, subplot involving a Buddhist vowing to get to the stars via teleportation.

a review by Rich Horton

Today would have been Fredric Brown's 112th birthday. In his honor, then, I decided to post a fairly brief review I did a long time ago, for my SFF Net newsgroup, of his novel The Lights in the Sky Are Stars.

Brown (1906-1972) was a well-respected writer in both the SF and Mystery genres, winning one Edgar for his novel The Fabulous Clipjoint. His work was often funny, though often with a serious, even dark, undertone. He was well-known for his very short stories. His best known short story is probably "Arena", which was anthologized in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, and which is considered a source for the Star Trek episode of the same title. Here's what I wrote back in 1999 (which is also when the novel is set):

I read an old SF novel I'd been meaning to try for some time, Fredric Brown's The Lights in the Sky Are Stars (1953). This tells of a spacestruck man in 1999, an aging spaceship mechanic, who becomes involved with a politician and her efforts to reignite America's space program by pushing for the development of a ship to Jupiter. It's mostly too cheesy and melodramatic to work: we need to put up with the hero breaking into an opposing politician's office to steal the meticulous records detailing his corruption, for instance, and with a tragic death, caused because a ten-day delay in getting the program started was impossible, and with the hero teaching himself spaceship administration in no time, and cutting the cost of the program from a near-prohibitive 300 million dollars (!) to 26 million dollars. Among other things. At the end there is another weird twist, almost the most melodramatic of all, which oddly almost works, and allows the novel to close on an effective, quite moving note. It's still a case of preaching to the choir, though. And in the final analysis I felt the cheesiness and implausibility of most of the novel doomed it.

By the by there are some neatly typical '50s predictions for 1999: TV remote controls, but those fixed to the living room chairs (!), private helicopters as a common means of travel, and chemical rockets planned to reach the moon by 1969. (But they switched to atomics and got there by 1965: too bad for Brown's prediction record.) There's also the odd '50s faith in progress uber alles: the lead character refuses to believe that light speed is a real limit (humanity's beat every other limit it's faced, by gum, it won't let a little thing like the special relativity stop it!), though to be fair that's only his attitude: the novel itself has no relativity-beating. And there is a curious, somewhat effective, subplot involving a Buddhist vowing to get to the stars via teleportation.

Birthday Review: Stories of Paul di Filippo

Today is Paul di Filippo's 64th birthday. So, it's time for another compilation of my Locus reviews -- lots of them this time, as Paul is a very prolific writer, and a writer whose work I greatly enjoy. The first review comes from Locus Online before I started reviewing for the print magazine -- I did a few reviews and essays for that site, edited by my predecessor as short fiction columnist, the excellent Mark Kelly (and doubtless those contributed to me getting the gig at the print version.)

(Locus Online, 12 April 2001)

It would be a shame if readers missed the long novella in the Spring 2001 issue of Fantastic Stories of the Imagination, one of the DNA Publications stable of magazines. This story is "Karuna, Inc.", by the always interesting Paul Di Filippo. Di Filippo works well at the novella length, and much of his best fiction is in that category, including the stories in The Steampunk Trilogy as well as such fine works as "The Mill" and "Spondulix".

"Karuna, Inc." (like "Spondulix", actually) presents a rather utopian view of economic activity. Shenda Moore is a brilliant young woman who took a nice inheritance and founded the title corporation, with the following mission: "the creation of environmentally responsible, non-exploitive, domestic-based, maximally creative jobs ... the primary goal of the subsidiaries shall always be the full employment of all workers ... it is to be hoped that the delivery of high-quality goods and services will be a byproduct ...". Without commenting on the likelihood of such a plan working in the real world, I'll just say that it would be nice if it would. But unfortunately, Shenda, though she doesn't know it, has an enemy: a consortium of maximally evil corporate types, led by the sinister Marmaduke Twigg.

The story is told alternately from the viewpoints of Shenda, Twigg, and a damaged veteran named Thurman Swan. As Shenda brings Thurman out of his shell of self-pity, Twigg comes to realize the existence of "Karuna, Inc." and moves against it. Di Filippo alternates sunny scenes of Thurman and Shenda with grotesque scenes of Twigg and his fellow evildoers, each of whom have a special operation to make them as evil as possible. The evil seems a bit over the top, and the good has a large dose of wish-fulfillment intermixed, but the story throughout is gripping, and the characters involving. It's a very fun read, mixing tragedy and optimism, mysticism and business, with Di Filippo's usual off-kilter imagination. Not a great story, but a good, enjoyable, one.

(Locus, February 2007)

And Paul Di Filippo, in "Wikiworld" (Fast Forward 1), engages in another of his utopian economic fantasias, this one about a world in which stuff gets done on the "wiki" model: a group of interested people competing and cooperating to build something. Such as house for our hero, Ross Reynolds, which leads to him running the country for three days, starting a trade war, and falls in love. Oh, and ganja on the Moon is involved too. Light-hearted, imaginative, fast-moving, sweet: lots of fun, like any number of similar Di Filippo pieces.

(Locus, November 2002)

Paul Di Filippo's "Shipbreaker" (Sci Fiction, October) is intriguing, about a man and two friends who are part of a crew of various species who salvage decommissioned starships. The hero, Klom, finds a curious alien in some sort of suspended animation, and after reviving it, adopts it as a pet. But it turns out to be something more than anyone expects. One interesting aspect of the story is the low position of humans in a galaxy dominated by much more intelligent species. The story does read like the opening segment of a novel rather than a complete story, however.

(Locus, December 2002)

The DAW mass market anthologies are a mixed lot -- some are quite awful, and some, like Mars Probes, are quite good. Once Upon a Galaxy, edited by Wil McCarthy with anthology veterans John Helfers and Martin H. Greenberg, is one of the better ones, if not so good as Mars Probes. The theme is "science fictional retellings of fairy tales", and most of the stories take a reasonably inventive approach -- sometimes a bit paint-by-numbers in replacing fantasy elements with Sfnal nuts and bolts, but still enjoyable. My favorite entry was Paul di Filippo's "Ailoura", a clever retelling of "Puss in Boots" on a far planet with genetically engineered animal-human chimeras, AI houses, immortality, and of course a younger son cheated out of his inheritance. Di Filippo throws in some nice Cordwainer Smith references for the SF initiates -- a very fun story. McCarthy's own "He Died that Day, in Thirty Years", is a clever and sardonic extrapolation of the unexpected effects of a slightly malfunctioning memory tailoring drug. Most of the rest of the book is decent entertainment as well.

Di Filippo is on a roll lately, though really he's been doing excellent stuff for a long time. His entry in the justly celebrated PS Publishing series of novella-length chapbooks, A Year in the Linear City, is one of the best novellas of this year. Di Filippo follows several episodes in the life of Diego Patchen, an up and coming writer of Cosmogonic Fiction, or CF, the Linear City's analog to SF. The plot turns on Diego's worries about his dying father, and his friend's obsession with a drug-addicted woman; as well as a trip down the city's border river to a distant borough. It's not really much of a plot, just a series of episodes. The fun is in di Filippo's description of the title City, which is very narrow but of unimaginable length, bordered by train tracks on one side and a river on the other side, and mounted, apparently, on some huge scaly beast. Di Filippo invents an engaging and convincing slang, sketches an interesting social/political/economic backgroun, and portrays any number of genially colorful characters, such as Diego's glorious fire-fighting girlfriend Volusia Bittern, or his editor at his main magazine market, an obvious John W. Campbell pastiche. The story is by turns pleasantly rambling, funny, sad, and full of sense of wonder. In general feel it recalls several of di Filippo's "alternate economy" novellas, such as "Karuna, Inc." and "Spondulix". Paul di Filippo is clearly one of the most original, and one of the best, SF writers now working, and while he is certainly not ignored, he does not seem to me to get quite the credit he is due. Perhaps that will soon change.

(Locus, March 2003)

There is also (in the November-December 2002 Interzone) a neat story by "Philip Lawson" (Michael Bishop and Paul di Filippo). "'We're All in This Together'" is about a serial murderer who seems to get inspiration from the banal sayings of a newspaper column called "The Squawk Box". A mystery writer obsessed with contributing a saying to this column ends up involved in the murder investigation. Rather loopy, but with a serious core.

(Locus, April 2003)

Also in the April issue of F&SF, Paul Di Filippo contributes "Seeing is Believing", about a private investigator and a beautiful scientist investigating a criminal who seems able to use his PDA to bypass his victims' brains "Executive Structure". Di Filippo takes a nice SFnal idea and wraps a fast-paced and funny caper story about it. It's not exactly believable but it's great fun.

(Locus, May 2003)

Last month at Interzone Paul Di Filippo and Michael Bishop were featured in collaboration. This month they each appear separately, with rather humorous pieces. Di Filippo's "Bare Market" tells of a journalist's interview with Adamina Smythe, the computer-enhanced genius girl who controls the world's financial markets, resulting in unprecedented prosperity. But Adamina, besides being a genius, is incredibly beautiful, and the journalist is smitten -- what will sex hormones in the system do to the world's fortunes?

(Locus, July 2003)

Perhaps best of all is Paul Di Filippo's "Clouds and Cold Fires" (Live Without a Net), in which the departed humans have left a revitalized Earth in the charge of long-lived, intelligent, genetically engineered chimeras of some sort. Pertinax and his friends must deal with a threat from one of the still technologically oriented "Overclockers", humans who have stayed behind on reservations, and who refuse to abandon the old ways.

(Locus, December 2003)

"The Dish Ran Away With the Spoon", by Paul Di Filippo (Sci Fiction, November), is a very funny and clever tale of "blebs" -- spontaneously generated AIs caused by linkages between random sets of "smart" appliances. These AIs don't always have the best interests of humans in their "minds", and Kas, who lost his parents to a bleb, becomes paranoid when his girlfriend Cody moves in with him: he's worried that their combined possessions might bring the assemblage to a sort of critical mass. But his paranoia starts to affect his relationship with Cody -- just the opening a newly formed AI needs! Fun stuff, sort of a Cory Doctorow/Charles Stross future refracted through Di Filippo's unique sensibility.

(Locus, March 2005)

But best this issue (Interzone, January-February) is Paul Di Filippo's "The Emperor of Gondwanaland". This is a Borgesian story (and knows it, as signaled by being partly set in Buenos Aires, and by the use of Funes as a name) about an overworked magazine editor who stumbles across internet references to micronations. One of these is Gondwanaland, which seems insanely detailed for what must be an imaginative creation. The man joins a discussion group, and eventually falls in love with a woman on one of the groups. She pushes for a meeting -- but how can he find Gondwanaland?

(Locus, April 2005)

From the April F&SF, Paul Di Filippo's "The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet" is an amusing story with a dark edge, about a struggling writer who has finally made it big. The problem is, Riley Small's bestseller, The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet, purports to be the memoirs of a 25 year old sexual adventuress. Now that a movie deal is in the offing, a 35 year old man just won't do as the public face of the author. So, Riley and his agent decide to hire an actress -- when a mysterious woman shows up and declares that she IS Sally Strumpet -- and to Riley, she seems perfect. Especially when she seems ready to continue her sexual adventuring -- with him. But every silver lining has a cloud ... Di Filippo is very entertaining on most subjects, particularly on the ups and downs of a writing career, as already well established by his Plumage for Pegasus pieces -- and this story is another delight.

(Locus, December 2009)

Paul Di Filippo’s "Yes We Have No Bananas" (Eclipse Three) is one of his wacky but serious pieces of economic extrapolation, mixing advanced physics (involving branes and parallel worlds) with a world in which ocarina music is the height of popularity. The lead character, Tug, is down on his luck -- his girlfriend has left him, he’s being evicted, he’s lost his job, and so he ends up on a houseboat drawing a comic strip with a beautiful young woman and helping a nutty physicist put on a play designed to demonstrate the correctness of his theories ...what can I say? It’s Paul Di Filippo.

(Locus, April 2011)

Paul di Filippo, in "FarmEarth" (Welcome to the Greenhouse), suggests that one way to make boring ecological remediation tasks more enjoyable might be to embed them in a gaming environment, and wraps a nice story around that about a group of kids too eager to take on more advanced responsibilities, who thus get involved in a dangerous conspiracy.

(Locus, November 2013)

Also good this month (Asimov's, October-November) is Paul di Filippo's "Adventures in Cognitive Homogamy: A Love Story", about a brilliant young researcher visiting a "Science Park" in Colombia, where he is seduced into a dangerous encounter with a beautiful member of the underprivileged classes -- followed by (perhaps a tad too predictable) consciousness-raising. Di Filippo also has the best story in the November Analog, "Redskins of the Badlands", which resembles "Adventures in Cognitive Harmony" in the featuring a somewhat innocent highly talented hero, betrayed at the outset by his beautiful lover, encountering a dissident group (and having sex …) The angle here is a bit different -- Ruy Lambeth spends most of his time in his "skin", guarding UNESCO world heritage sites from the depredations of people like a group of ecoterrorists menacing Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta. Both stories are a bit thin towards the end -- mostly interested in introducing some neat tech in the context of a somewhat optimistic (but far from perfect) future society ...But both are fun rides along the way.

(Locus Online, 12 April 2001)

It would be a shame if readers missed the long novella in the Spring 2001 issue of Fantastic Stories of the Imagination, one of the DNA Publications stable of magazines. This story is "Karuna, Inc.", by the always interesting Paul Di Filippo. Di Filippo works well at the novella length, and much of his best fiction is in that category, including the stories in The Steampunk Trilogy as well as such fine works as "The Mill" and "Spondulix".

"Karuna, Inc." (like "Spondulix", actually) presents a rather utopian view of economic activity. Shenda Moore is a brilliant young woman who took a nice inheritance and founded the title corporation, with the following mission: "the creation of environmentally responsible, non-exploitive, domestic-based, maximally creative jobs ... the primary goal of the subsidiaries shall always be the full employment of all workers ... it is to be hoped that the delivery of high-quality goods and services will be a byproduct ...". Without commenting on the likelihood of such a plan working in the real world, I'll just say that it would be nice if it would. But unfortunately, Shenda, though she doesn't know it, has an enemy: a consortium of maximally evil corporate types, led by the sinister Marmaduke Twigg.

The story is told alternately from the viewpoints of Shenda, Twigg, and a damaged veteran named Thurman Swan. As Shenda brings Thurman out of his shell of self-pity, Twigg comes to realize the existence of "Karuna, Inc." and moves against it. Di Filippo alternates sunny scenes of Thurman and Shenda with grotesque scenes of Twigg and his fellow evildoers, each of whom have a special operation to make them as evil as possible. The evil seems a bit over the top, and the good has a large dose of wish-fulfillment intermixed, but the story throughout is gripping, and the characters involving. It's a very fun read, mixing tragedy and optimism, mysticism and business, with Di Filippo's usual off-kilter imagination. Not a great story, but a good, enjoyable, one.

(Locus, February 2007)

And Paul Di Filippo, in "Wikiworld" (Fast Forward 1), engages in another of his utopian economic fantasias, this one about a world in which stuff gets done on the "wiki" model: a group of interested people competing and cooperating to build something. Such as house for our hero, Ross Reynolds, which leads to him running the country for three days, starting a trade war, and falls in love. Oh, and ganja on the Moon is involved too. Light-hearted, imaginative, fast-moving, sweet: lots of fun, like any number of similar Di Filippo pieces.

(Locus, November 2002)

Paul Di Filippo's "Shipbreaker" (Sci Fiction, October) is intriguing, about a man and two friends who are part of a crew of various species who salvage decommissioned starships. The hero, Klom, finds a curious alien in some sort of suspended animation, and after reviving it, adopts it as a pet. But it turns out to be something more than anyone expects. One interesting aspect of the story is the low position of humans in a galaxy dominated by much more intelligent species. The story does read like the opening segment of a novel rather than a complete story, however.

(Locus, December 2002)

The DAW mass market anthologies are a mixed lot -- some are quite awful, and some, like Mars Probes, are quite good. Once Upon a Galaxy, edited by Wil McCarthy with anthology veterans John Helfers and Martin H. Greenberg, is one of the better ones, if not so good as Mars Probes. The theme is "science fictional retellings of fairy tales", and most of the stories take a reasonably inventive approach -- sometimes a bit paint-by-numbers in replacing fantasy elements with Sfnal nuts and bolts, but still enjoyable. My favorite entry was Paul di Filippo's "Ailoura", a clever retelling of "Puss in Boots" on a far planet with genetically engineered animal-human chimeras, AI houses, immortality, and of course a younger son cheated out of his inheritance. Di Filippo throws in some nice Cordwainer Smith references for the SF initiates -- a very fun story. McCarthy's own "He Died that Day, in Thirty Years", is a clever and sardonic extrapolation of the unexpected effects of a slightly malfunctioning memory tailoring drug. Most of the rest of the book is decent entertainment as well.

Di Filippo is on a roll lately, though really he's been doing excellent stuff for a long time. His entry in the justly celebrated PS Publishing series of novella-length chapbooks, A Year in the Linear City, is one of the best novellas of this year. Di Filippo follows several episodes in the life of Diego Patchen, an up and coming writer of Cosmogonic Fiction, or CF, the Linear City's analog to SF. The plot turns on Diego's worries about his dying father, and his friend's obsession with a drug-addicted woman; as well as a trip down the city's border river to a distant borough. It's not really much of a plot, just a series of episodes. The fun is in di Filippo's description of the title City, which is very narrow but of unimaginable length, bordered by train tracks on one side and a river on the other side, and mounted, apparently, on some huge scaly beast. Di Filippo invents an engaging and convincing slang, sketches an interesting social/political/economic backgroun, and portrays any number of genially colorful characters, such as Diego's glorious fire-fighting girlfriend Volusia Bittern, or his editor at his main magazine market, an obvious John W. Campbell pastiche. The story is by turns pleasantly rambling, funny, sad, and full of sense of wonder. In general feel it recalls several of di Filippo's "alternate economy" novellas, such as "Karuna, Inc." and "Spondulix". Paul di Filippo is clearly one of the most original, and one of the best, SF writers now working, and while he is certainly not ignored, he does not seem to me to get quite the credit he is due. Perhaps that will soon change.

(Locus, March 2003)

There is also (in the November-December 2002 Interzone) a neat story by "Philip Lawson" (Michael Bishop and Paul di Filippo). "'We're All in This Together'" is about a serial murderer who seems to get inspiration from the banal sayings of a newspaper column called "The Squawk Box". A mystery writer obsessed with contributing a saying to this column ends up involved in the murder investigation. Rather loopy, but with a serious core.

(Locus, April 2003)

Also in the April issue of F&SF, Paul Di Filippo contributes "Seeing is Believing", about a private investigator and a beautiful scientist investigating a criminal who seems able to use his PDA to bypass his victims' brains "Executive Structure". Di Filippo takes a nice SFnal idea and wraps a fast-paced and funny caper story about it. It's not exactly believable but it's great fun.

(Locus, May 2003)

Last month at Interzone Paul Di Filippo and Michael Bishop were featured in collaboration. This month they each appear separately, with rather humorous pieces. Di Filippo's "Bare Market" tells of a journalist's interview with Adamina Smythe, the computer-enhanced genius girl who controls the world's financial markets, resulting in unprecedented prosperity. But Adamina, besides being a genius, is incredibly beautiful, and the journalist is smitten -- what will sex hormones in the system do to the world's fortunes?

(Locus, July 2003)

Perhaps best of all is Paul Di Filippo's "Clouds and Cold Fires" (Live Without a Net), in which the departed humans have left a revitalized Earth in the charge of long-lived, intelligent, genetically engineered chimeras of some sort. Pertinax and his friends must deal with a threat from one of the still technologically oriented "Overclockers", humans who have stayed behind on reservations, and who refuse to abandon the old ways.

(Locus, December 2003)

"The Dish Ran Away With the Spoon", by Paul Di Filippo (Sci Fiction, November), is a very funny and clever tale of "blebs" -- spontaneously generated AIs caused by linkages between random sets of "smart" appliances. These AIs don't always have the best interests of humans in their "minds", and Kas, who lost his parents to a bleb, becomes paranoid when his girlfriend Cody moves in with him: he's worried that their combined possessions might bring the assemblage to a sort of critical mass. But his paranoia starts to affect his relationship with Cody -- just the opening a newly formed AI needs! Fun stuff, sort of a Cory Doctorow/Charles Stross future refracted through Di Filippo's unique sensibility.

(Locus, March 2005)

But best this issue (Interzone, January-February) is Paul Di Filippo's "The Emperor of Gondwanaland". This is a Borgesian story (and knows it, as signaled by being partly set in Buenos Aires, and by the use of Funes as a name) about an overworked magazine editor who stumbles across internet references to micronations. One of these is Gondwanaland, which seems insanely detailed for what must be an imaginative creation. The man joins a discussion group, and eventually falls in love with a woman on one of the groups. She pushes for a meeting -- but how can he find Gondwanaland?

(Locus, April 2005)

From the April F&SF, Paul Di Filippo's "The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet" is an amusing story with a dark edge, about a struggling writer who has finally made it big. The problem is, Riley Small's bestseller, The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet, purports to be the memoirs of a 25 year old sexual adventuress. Now that a movie deal is in the offing, a 35 year old man just won't do as the public face of the author. So, Riley and his agent decide to hire an actress -- when a mysterious woman shows up and declares that she IS Sally Strumpet -- and to Riley, she seems perfect. Especially when she seems ready to continue her sexual adventuring -- with him. But every silver lining has a cloud ... Di Filippo is very entertaining on most subjects, particularly on the ups and downs of a writing career, as already well established by his Plumage for Pegasus pieces -- and this story is another delight.

(Locus, December 2009)

Paul Di Filippo’s "Yes We Have No Bananas" (Eclipse Three) is one of his wacky but serious pieces of economic extrapolation, mixing advanced physics (involving branes and parallel worlds) with a world in which ocarina music is the height of popularity. The lead character, Tug, is down on his luck -- his girlfriend has left him, he’s being evicted, he’s lost his job, and so he ends up on a houseboat drawing a comic strip with a beautiful young woman and helping a nutty physicist put on a play designed to demonstrate the correctness of his theories ...what can I say? It’s Paul Di Filippo.

(Locus, April 2011)

Paul di Filippo, in "FarmEarth" (Welcome to the Greenhouse), suggests that one way to make boring ecological remediation tasks more enjoyable might be to embed them in a gaming environment, and wraps a nice story around that about a group of kids too eager to take on more advanced responsibilities, who thus get involved in a dangerous conspiracy.

(Locus, November 2013)

Also good this month (Asimov's, October-November) is Paul di Filippo's "Adventures in Cognitive Homogamy: A Love Story", about a brilliant young researcher visiting a "Science Park" in Colombia, where he is seduced into a dangerous encounter with a beautiful member of the underprivileged classes -- followed by (perhaps a tad too predictable) consciousness-raising. Di Filippo also has the best story in the November Analog, "Redskins of the Badlands", which resembles "Adventures in Cognitive Harmony" in the featuring a somewhat innocent highly talented hero, betrayed at the outset by his beautiful lover, encountering a dissident group (and having sex …) The angle here is a bit different -- Ruy Lambeth spends most of his time in his "skin", guarding UNESCO world heritage sites from the depredations of people like a group of ecoterrorists menacing Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta. Both stories are a bit thin towards the end -- mostly interested in introducing some neat tech in the context of a somewhat optimistic (but far from perfect) future society ...But both are fun rides along the way.

Sunday, October 28, 2018

Birthday Review: Stories of Richard A. Lovett

Richard A. Lovett is one of Analog's most regular contributors (of non-fiction as well as fiction), and one of its best. Today is his 65th birthday, and so here is a compilations of many of my Locus reviews of his stories.

(Locus, March 2003)

More interesting in the March issue of Analog is Richard A. Lovett's "Equalization", which addresses an elaborate version of the idea at the heart of Kurt Vonnegut's classic "Harrison Bergeron". In Lovett's story, people choose a career in early adolescence, and from that point forward they are transferred to new bodies each year. The idea is to balance skilled minds with less-skilled bodies, so that competition within a field is roughly equal. The story itself concerns a long-distance runner who realizes that he has been, presumably by mistake, transferred to his own original body, giving him a huge advantage. The idea here is quite interesting, but the story itself doesn't quite work, and the full ramifications of the central idea don't really hold together.

(Locus, September 2003)

The September Analog's strongest story is Richard Lovett's "Tiny Berries", which postulates even worse spam than now -- to the point of intercepting cars and extorting sales. The hero and a couple of friends come up with a solution (probably not workable but interesting) -- wrapped around a sweet but not really convincing love story.

(Locus, January 2004)

Richard A. Lovett's "Weapons of Mass Distraction" (Analog, January-February) extrapolates Patriot Act-like anti-terrorist measures to extremes, making a point about the real consequences -- and one beneficiary -- of such invasions of privacy.

(Locus, June 2005)

Richard Lovett and Mark Niemann-Ross in "NetPuppets" (Analog, June 2005) posit a Sims-like online game. A group of co-workers discover the game and create a couple of characters. The game adds detail to the characters, sometimes making subtle changes. The players try to alter their characters' lives, but unlike with Sims their actions are constrained to fairly plausible real-life actions -- for example, they cannot make a character win the lottery, but they can push her towards a better job. But they might also push their characters in negative ways -- or in criminal ways. But so what? It's only a game, right? The twist is predictable but well-handled, and the moral point, expressed through several characters, is sharply put.

(Locus, November 2005)

I also liked Richard A. Lovett’s "911-Backup", which as with many of Lovett’s stories deals intelligently with the problem areas of future tech, in ideal Analog fashion. In this case the tech is brain capacity enhancement via computer implant, and the problem is "What happens if the computer crashes, and you have offloaded too much capacity away from your brain onto the computer?"

(Locus, February 2007)

Richard A. Lovett’s "The Unrung Bells of the Marie Celeste" (Analog, January-February), is an interesting look at an idea I’ve seen once or twice before: FTL that works fine for unmanned missions but that fails whenever a human is the pilot. (For example, the fairly obscure Poul Anderson story "Mustn’t Touch".) Lovett’s reason why it doesn’t work is clever and also leads to an interesting personal story about his main character, a man chosen for a test flight because he is suicidal.

(Locus, October 2009)

Abyss and Apex for the third quarter includes a Richard A. Lovett story, "Carpe Mañana", that, as often with Lovett, thoroughly explores the social implications of a technological innovation -- his work in this vein reminds me of H. L. Gold’s Galaxy more than about any contemporary writer I can recall. The innovation explored here is the stasis box -- a fairly old SF idea, a box in which no time passes. It’s first used for food preservation -- no need for refrigeration if you can just pop in the fresh food and use it when needed. But Lovett, in a series of short pieces, shows its use by humans -- a daughter trying to escape contact with her parents, a man with Seasonal Affective Disorder skipping winter, prisoners warehoused until their cases are decided, etc. It’s thoughtful and often scary.

(Locus, July 2011)

I mentioned Jack and the Beanstalk stories last month and look! This month Analog has one. in the July-August 2011 issue. It’s called "Jak and the Beanstalk", by Richard A. Lovett, and I don’t think it will surprise anyone to learn that the Beanstalk of the title is a space elevator. Jak spends his life planning to climb the Beanstalk, a rather mad enterprise, and the first part of the story is devoted to showing how one might do that ... which to be honest isn’t terribly compelling as narrative. But the story gets rather better when war breaks out while Jak is on his way up -- making his position on the Beanstalk arguably better than anyone’s on Earth. And when he gets to the geosynchronous part of the Beanstalk and finds the maintenance crew attempting to survive, his priorities change -- in a way he finally really grows up, and ends up heading elsewhere. Lovett is probably Analog’s best current regular writer -- a writer who fits snugly within the Analog format yet does thought-provoking and interesting and continually different work within it.

(Locus, August 2012)

At the July/August Analog the cover story is "Nightfall on the Peak of Eternal Light", by Richard Lovett and William Gleason, a Moon colonization story. It focuses on a man trying to immigrate to the Moon, as part of a witness protection program. The problem is, it's hard to earn your ticket to stay ... not to mention, it turns out to be easy enough to be found even if you do stay. The ideas about why and how the Moon might be colonized are interesting, and the central plot is enjoyable enough, though the story is probably a bit too long.

(Locus, February 2015)

Analog's big Double Issue for January-February features "Defender of Worms", a novella from Richard Lovett, the latest in a long series of stories about an AI named Brittney. Freed by her first owner, who lives in the outer Solar System, she is back on Earth and acting as a sort of governess for a rebellious rich girl named Memphis. But Brittney is being hunted by another AI, which she calls the Others, and Memphis wants to escape her mother's influence, so the two have lit out for the desolate American West, off the grid. But the enemy has resources, and Memphis has a lot of learning to do, besides Brittney needing to learn to live with Memphis. This is good, entertaining SF, with plenty of action and some nice (if not terribly new) ideas behind it.

(Locus, March 2003)

More interesting in the March issue of Analog is Richard A. Lovett's "Equalization", which addresses an elaborate version of the idea at the heart of Kurt Vonnegut's classic "Harrison Bergeron". In Lovett's story, people choose a career in early adolescence, and from that point forward they are transferred to new bodies each year. The idea is to balance skilled minds with less-skilled bodies, so that competition within a field is roughly equal. The story itself concerns a long-distance runner who realizes that he has been, presumably by mistake, transferred to his own original body, giving him a huge advantage. The idea here is quite interesting, but the story itself doesn't quite work, and the full ramifications of the central idea don't really hold together.

(Locus, September 2003)

The September Analog's strongest story is Richard Lovett's "Tiny Berries", which postulates even worse spam than now -- to the point of intercepting cars and extorting sales. The hero and a couple of friends come up with a solution (probably not workable but interesting) -- wrapped around a sweet but not really convincing love story.

(Locus, January 2004)

Richard A. Lovett's "Weapons of Mass Distraction" (Analog, January-February) extrapolates Patriot Act-like anti-terrorist measures to extremes, making a point about the real consequences -- and one beneficiary -- of such invasions of privacy.

(Locus, June 2005)

Richard Lovett and Mark Niemann-Ross in "NetPuppets" (Analog, June 2005) posit a Sims-like online game. A group of co-workers discover the game and create a couple of characters. The game adds detail to the characters, sometimes making subtle changes. The players try to alter their characters' lives, but unlike with Sims their actions are constrained to fairly plausible real-life actions -- for example, they cannot make a character win the lottery, but they can push her towards a better job. But they might also push their characters in negative ways -- or in criminal ways. But so what? It's only a game, right? The twist is predictable but well-handled, and the moral point, expressed through several characters, is sharply put.

(Locus, November 2005)

I also liked Richard A. Lovett’s "911-Backup", which as with many of Lovett’s stories deals intelligently with the problem areas of future tech, in ideal Analog fashion. In this case the tech is brain capacity enhancement via computer implant, and the problem is "What happens if the computer crashes, and you have offloaded too much capacity away from your brain onto the computer?"

(Locus, February 2007)

Richard A. Lovett’s "The Unrung Bells of the Marie Celeste" (Analog, January-February), is an interesting look at an idea I’ve seen once or twice before: FTL that works fine for unmanned missions but that fails whenever a human is the pilot. (For example, the fairly obscure Poul Anderson story "Mustn’t Touch".) Lovett’s reason why it doesn’t work is clever and also leads to an interesting personal story about his main character, a man chosen for a test flight because he is suicidal.

(Locus, October 2009)

Abyss and Apex for the third quarter includes a Richard A. Lovett story, "Carpe Mañana", that, as often with Lovett, thoroughly explores the social implications of a technological innovation -- his work in this vein reminds me of H. L. Gold’s Galaxy more than about any contemporary writer I can recall. The innovation explored here is the stasis box -- a fairly old SF idea, a box in which no time passes. It’s first used for food preservation -- no need for refrigeration if you can just pop in the fresh food and use it when needed. But Lovett, in a series of short pieces, shows its use by humans -- a daughter trying to escape contact with her parents, a man with Seasonal Affective Disorder skipping winter, prisoners warehoused until their cases are decided, etc. It’s thoughtful and often scary.

(Locus, July 2011)

I mentioned Jack and the Beanstalk stories last month and look! This month Analog has one. in the July-August 2011 issue. It’s called "Jak and the Beanstalk", by Richard A. Lovett, and I don’t think it will surprise anyone to learn that the Beanstalk of the title is a space elevator. Jak spends his life planning to climb the Beanstalk, a rather mad enterprise, and the first part of the story is devoted to showing how one might do that ... which to be honest isn’t terribly compelling as narrative. But the story gets rather better when war breaks out while Jak is on his way up -- making his position on the Beanstalk arguably better than anyone’s on Earth. And when he gets to the geosynchronous part of the Beanstalk and finds the maintenance crew attempting to survive, his priorities change -- in a way he finally really grows up, and ends up heading elsewhere. Lovett is probably Analog’s best current regular writer -- a writer who fits snugly within the Analog format yet does thought-provoking and interesting and continually different work within it.

(Locus, August 2012)

At the July/August Analog the cover story is "Nightfall on the Peak of Eternal Light", by Richard Lovett and William Gleason, a Moon colonization story. It focuses on a man trying to immigrate to the Moon, as part of a witness protection program. The problem is, it's hard to earn your ticket to stay ... not to mention, it turns out to be easy enough to be found even if you do stay. The ideas about why and how the Moon might be colonized are interesting, and the central plot is enjoyable enough, though the story is probably a bit too long.

(Locus, February 2015)

Analog's big Double Issue for January-February features "Defender of Worms", a novella from Richard Lovett, the latest in a long series of stories about an AI named Brittney. Freed by her first owner, who lives in the outer Solar System, she is back on Earth and acting as a sort of governess for a rebellious rich girl named Memphis. But Brittney is being hunted by another AI, which she calls the Others, and Memphis wants to escape her mother's influence, so the two have lit out for the desolate American West, off the grid. But the enemy has resources, and Memphis has a lot of learning to do, besides Brittney needing to learn to live with Memphis. This is good, entertaining SF, with plenty of action and some nice (if not terribly new) ideas behind it.

Ace Double Reviews, 14: Cosmic Checkmate, by Charles V. De Vet and Katherine MacLean/King of the Fourth Planet, by Robert Moore Williams

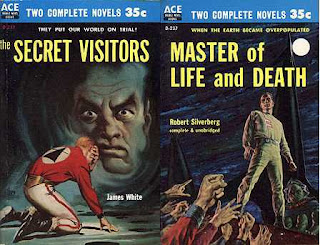

Ace Double Reviews, 14: Cosmic Checkmate, by Charles V. De Vet and Katherine MacLean/King of the Fourth Planet, by Robert Moore Williams (#F-149, 1962, $0.40)

On what would have been Charles V. De Vet's 107th birthday, I'm reposting one of my personal favorites among my Ace Double reviews -- not because the books are my favorites, but because I had a lots of fun tracking down the extended history of the De Vet/MacLean novel and its sequel.

King of the Fourth Planet is about 43,000 words long. Cosmic Checkmate is about 33,000 words, and it has a complicated publishing history. It's an expansion (by a factor of roughly 2) of the novelette "Second Game" (Astounding, March 1958), a Hugo nominee and still a fairly well-known story. The novel was reissued in 1981 by DAW with further expansions, to some 56,000 words, now retitled Second Game after the novelette. (A much better title!) Finally, De Vet by himself wrote a sequel published in the February 1991 Analog, called "Third Game".

Neither of the authors of Cosmic Checkmate was terribly prolific, indeed, their quantity of output is strikingly similar: 30 or 40 stories and one solo novel each. De Vet (1911-1997) began publishing in 1950, and through 1962 published a couple of dozen stories. Over the next couple of decades he published far less often, just 8 more stories according to the ISFDB, several in Ted White's mid-70s Amazing, with "Third Game" his last story. He published just one additional novel, Special Feature (1975), another expansion of a 1958 Astounding novelette ("Special Feature", May 1958). MacLean (b. 1925), is deservedly the better known. She is this year's SFWA Writer Emeritus (2003). She began publishing in 1949, and has had a story in Analog as recently as "Kiss Me" (February 1997), which made the Hartwell Year's Best #3. Her best-known story is almost certainly "The Missing Man" (Analog, March 1971), which won a Nebula for Best Novella, and which was expanded to her only solo novel, Missing Man (1975). (She has published one other collaborative novel, Dark Wing, (1979), with Carl West, which I haven't seen but which appears to be a YA Fantasy.) Other stories such as "Contagion" (1950), "Pictures Don't Lie" (1951), "The Snowball Effect" (1952), "The Diploids" (1953), "The Trouble With You Earth People" (1968), and "The Kidnapping of Baroness 5" (1995), gained considerable notice.

Robert Moore Williams (1907-1977) was a fairly regular writer for the SF magazines beginning in the late 30s, and ending in 1965-1966 with a sudden spurt of 4 stories for Fred Pohl's If after roughly a decade of publishing no short fiction. He also published quite a few novels in the field, including 11 Ace Double halves (in 9 books -- two of his halves were story collections that backed his own novels). Based on what I've read of his work, he wasn't really very good, and presumably as a result he is all but forgotten now. He might have been best known for a series of Edgar Rice Burroughs-like stories about heroes named Zanthar and Jongor, which appeared from Lancer and Popular Library from 1966 through 1970. (The Jongor books were reprints (perhaps expanded) of stories from Fantastic Adventures between 1940 and 1951, and the 1970 editions had Frazetta covers, which I am pretty sure I saw back in the day, though I never read them.)

King of the Fourth Planet is pretty straightforward SF. John Rolf is a former executive of the Company for Planetary Development who has repented of his unethical ways, and moved to Mars, divorcing his wife and leaving her with their young daughter when she refuses to accompany him. Rolf lives on the giant mountain Suzusilam, where most of the Martians live. The mountain (perhaps a "prediction" of Olympus Mons, which wasn't discovered until 1971) is divided into seven levels, on each of which live Martians of increasing "civilizedness". The fourth level is the home of the Martians at roughly Earth levels of development. The seventh level is reputedly home only to the mysterious King of the Red Planet, a Martian of incredible powers who "holds the mountain in his hand". Rolf lives on the fourth level, home to many mechanical geniuses, and he himself is working on a telepathy machine, which he hopes will solve humanity's problems by giving all people understanding of others. He is assisted at times by his friend Thallen from the fifth level. Just as he completes his machine, a Human spaceship lands, and Rolf senses the evil mind of the Company executive controlling the spaceship. Before you know it, this man, Jim Hardesty, shows up at Rolf's doorstep, demanding his assistance in cheating the Martians. Rolf refuses, whereupon Hardesty reveals that he has hired Rolf's daughter as his secretary (i.e. potential sex slave), but Rolf, with his daughter's help, continues to refuse. Soon a man shows up who has fallen in love with Rolf's daughter, but then Hardesty mounts an attack on the Martians, the daughter is kidnapped, Rolf is injured and his mind becomes detached from his body, and all leads to a confrontation on the seventh level with the mysterious King.

It's mostly a pretty bad book. Some of it is slapdash, such as having people run up and down this presumably huge mountain in no more than a couple of hours. The action develops too quickly, and not logically, and plot threads and ideas that showed promise (or not) are often as not brushed aside without resolution, or with unsatisfactory resolution. There are some nice bits -- the climactic scene at the top of the mountain is pretty impressive in parts, the advanced Martian tech represented by "abacuses" that play musical notes which cause healing and other powers is really kind of nicely depicted, the ethical message advanced, if crudely put, seems deeply felt and not unreasonable. Still -- not really a book worth attention. And not any reason to reconsider Williams' place in the canon.

Second Game is rather better. It's the story of the planet Velda, which has just been discovered by the Earth-centered Ten Thousand Worlds. After warning that they wanted no contact, the Veldians destroyed the Fleet that Earth sent anyway. The narrator, a chess champion, has learned that the Veldians base their society around proficiency in a Game, somewhat like Chess but more complicated. (Details are sketchy, but it is played on a 13x13 board, and each player controls 26 pieces, or "pukts".) Equipped with an "annotator", sort of an AI addition to his brain, the narrator learns the Game and comes to Velda to challenge all comers. He puts up a sign saying "I'll beat you the Second Game". And after probing the opponents' weaknesses by playing the first game, he does indeed beat them the second time. He finally draws the attention of Kalin Trobt, a high official and thus a proficient Game player. After the most difficult Game yet, the narrator again prevails, but Trobt perceives that he is a human, and arrests him as a spy.

Veldian society is predicated on exaggerated concepts of honor, and on absolute honesty. So the narrator is simply placed under house arrest at Trobt's house, though he is told that he will die, in the "Final Game". Over the next couple of weeks, the narrator and Trobt become friends, but the narrator's fate remains sealed. Both probe each other for secrets about their respective societies, and in particular a biological reason for much of the Veldian situation is revealed. Finally the narrator comes up with a surprising solution to his problem, and to Velda's problem, and eventually to the Ten Thousand Worlds' problem.

This short novel is a quick, entertaining, and generally absorbing read. It's not quite convincing -- the Game is marginally plausible, but not the narrator's proficiency. The Veldian social structure, and military prowess, both seem rather artificial. I didn't quite buy the biological problem at the heart of Veldian society either. Indeed, Veldqan biology as portrayed seems truly implausible -- I can't believe this race would survive! Other problems were lesser, such as the magical ability of Veldians and Humans to interbreed (this problem could easily have been finessed by a reference to panspermia or a lost colony or something, but instead the Veldians are supposed to be true aliens). Still, overall the story is enjoyable and thoughtful.

I read the novelette "Second Game" and the novel Cosmic Checkmate back to back. It's interesting how closely they resemble each other. The novel is not an extension, but an organic expansion, without even much in the way of added subplots. There is a somewhat unconvincing love interest for the narrator in the novel which is absent in the novelette.* Otherwise the expansions are all fleshed out scenes, added explanations. I think it actually works pretty well -- the novel does not seem padded.

I followed this by reading the 1981 DAW novel, Second Game. This is longer still, and it also features some curious changes. The changes include: changing the planet's name from Velda to Veldq (presumably to make it more "alien", and also perhaps to avoid sounding like a woman's name), changing the narrator's name from Robert O. Lang to Leonard Stromberg (a change I utterly fail to understand unless perhaps that was the original name, and John Campbell insisted on a more Anglo-Saxon lead character), and adding a new social group to Veldq society, the Kismans, low-status merchants. Further changes include more bald exposition of the Ten Thousand Worlds' situation, an altered (and not terribly believable) explanation for the Veldqan level of technology, a hugely expanded subplot about the narrator's Veldqan love interest, including some rather embarrassing sex scenes (and a revised account of the relationship of the sexes on Veldq), and a fair amount of small interpolations, fleshing out details.

On balance I think I prefer the shorter 1962 novel to the 1981 expansion: some of the 1981 additions are sensible fleshing out, but some are silly. The expanded love story is logical and fills in something missing in the 1962 version, but it's not very well done. Other additions, such as the Kismans and the new explanation of Veldqan tech, seem either superfluous or wrong. I wouldn't say, however, that the 1981 version feels padded -- the novelette, in retrospect, seems somewhat rushed, and I would have to say the story basically supports at least 50,000 words.

Finally I went ahead and read the 1991 novelette sequel, by De Vet alone, "Third Game". This is about 15,000 words long. It's set 23 years after the main action of Second Game. There are severe social problems on Veldq, and Leonard Stromberg's half-Veldqan son, Kalin Stromberg, comes to the planet to try to help. After some more harsh evidence of the silly over-violent Veldqan society, and another sometimes embarrassing highly sexed romance, which involved dealing fairly with the oppressed Kisman minority**, and, get this (shades of Asimov's The Stars Like Dust) -- adopt a constitution modelled on the US constitution. It's really a very bad story.

(*There was a curious brief mention of the girl who becomes the narrator's love interest in the novelette -- on reading that, bells went off in my head, and I was surprised that she did not reappear in the story. Which makes me wonder if the novelette wasn't cut before publication, as opposed to the novel being a later expansion.)

(**The Kismans are important in this story as they weren't in the 1981 Second Game, making me wonder if De Vet hadn't already written a version of "Third Game" when he (and MacLean) expanded Cosmic Checkmate to Second Game.)

On what would have been Charles V. De Vet's 107th birthday, I'm reposting one of my personal favorites among my Ace Double reviews -- not because the books are my favorites, but because I had a lots of fun tracking down the extended history of the De Vet/MacLean novel and its sequel.

King of the Fourth Planet is about 43,000 words long. Cosmic Checkmate is about 33,000 words, and it has a complicated publishing history. It's an expansion (by a factor of roughly 2) of the novelette "Second Game" (Astounding, March 1958), a Hugo nominee and still a fairly well-known story. The novel was reissued in 1981 by DAW with further expansions, to some 56,000 words, now retitled Second Game after the novelette. (A much better title!) Finally, De Vet by himself wrote a sequel published in the February 1991 Analog, called "Third Game".

|

| (Covers by Ed Emswhiller and Ed Valigursky) |

Neither of the authors of Cosmic Checkmate was terribly prolific, indeed, their quantity of output is strikingly similar: 30 or 40 stories and one solo novel each. De Vet (1911-1997) began publishing in 1950, and through 1962 published a couple of dozen stories. Over the next couple of decades he published far less often, just 8 more stories according to the ISFDB, several in Ted White's mid-70s Amazing, with "Third Game" his last story. He published just one additional novel, Special Feature (1975), another expansion of a 1958 Astounding novelette ("Special Feature", May 1958). MacLean (b. 1925), is deservedly the better known. She is this year's SFWA Writer Emeritus (2003). She began publishing in 1949, and has had a story in Analog as recently as "Kiss Me" (February 1997), which made the Hartwell Year's Best #3. Her best-known story is almost certainly "The Missing Man" (Analog, March 1971), which won a Nebula for Best Novella, and which was expanded to her only solo novel, Missing Man (1975). (She has published one other collaborative novel, Dark Wing, (1979), with Carl West, which I haven't seen but which appears to be a YA Fantasy.) Other stories such as "Contagion" (1950), "Pictures Don't Lie" (1951), "The Snowball Effect" (1952), "The Diploids" (1953), "The Trouble With You Earth People" (1968), and "The Kidnapping of Baroness 5" (1995), gained considerable notice.

Robert Moore Williams (1907-1977) was a fairly regular writer for the SF magazines beginning in the late 30s, and ending in 1965-1966 with a sudden spurt of 4 stories for Fred Pohl's If after roughly a decade of publishing no short fiction. He also published quite a few novels in the field, including 11 Ace Double halves (in 9 books -- two of his halves were story collections that backed his own novels). Based on what I've read of his work, he wasn't really very good, and presumably as a result he is all but forgotten now. He might have been best known for a series of Edgar Rice Burroughs-like stories about heroes named Zanthar and Jongor, which appeared from Lancer and Popular Library from 1966 through 1970. (The Jongor books were reprints (perhaps expanded) of stories from Fantastic Adventures between 1940 and 1951, and the 1970 editions had Frazetta covers, which I am pretty sure I saw back in the day, though I never read them.)

King of the Fourth Planet is pretty straightforward SF. John Rolf is a former executive of the Company for Planetary Development who has repented of his unethical ways, and moved to Mars, divorcing his wife and leaving her with their young daughter when she refuses to accompany him. Rolf lives on the giant mountain Suzusilam, where most of the Martians live. The mountain (perhaps a "prediction" of Olympus Mons, which wasn't discovered until 1971) is divided into seven levels, on each of which live Martians of increasing "civilizedness". The fourth level is the home of the Martians at roughly Earth levels of development. The seventh level is reputedly home only to the mysterious King of the Red Planet, a Martian of incredible powers who "holds the mountain in his hand". Rolf lives on the fourth level, home to many mechanical geniuses, and he himself is working on a telepathy machine, which he hopes will solve humanity's problems by giving all people understanding of others. He is assisted at times by his friend Thallen from the fifth level. Just as he completes his machine, a Human spaceship lands, and Rolf senses the evil mind of the Company executive controlling the spaceship. Before you know it, this man, Jim Hardesty, shows up at Rolf's doorstep, demanding his assistance in cheating the Martians. Rolf refuses, whereupon Hardesty reveals that he has hired Rolf's daughter as his secretary (i.e. potential sex slave), but Rolf, with his daughter's help, continues to refuse. Soon a man shows up who has fallen in love with Rolf's daughter, but then Hardesty mounts an attack on the Martians, the daughter is kidnapped, Rolf is injured and his mind becomes detached from his body, and all leads to a confrontation on the seventh level with the mysterious King.

It's mostly a pretty bad book. Some of it is slapdash, such as having people run up and down this presumably huge mountain in no more than a couple of hours. The action develops too quickly, and not logically, and plot threads and ideas that showed promise (or not) are often as not brushed aside without resolution, or with unsatisfactory resolution. There are some nice bits -- the climactic scene at the top of the mountain is pretty impressive in parts, the advanced Martian tech represented by "abacuses" that play musical notes which cause healing and other powers is really kind of nicely depicted, the ethical message advanced, if crudely put, seems deeply felt and not unreasonable. Still -- not really a book worth attention. And not any reason to reconsider Williams' place in the canon.

Second Game is rather better. It's the story of the planet Velda, which has just been discovered by the Earth-centered Ten Thousand Worlds. After warning that they wanted no contact, the Veldians destroyed the Fleet that Earth sent anyway. The narrator, a chess champion, has learned that the Veldians base their society around proficiency in a Game, somewhat like Chess but more complicated. (Details are sketchy, but it is played on a 13x13 board, and each player controls 26 pieces, or "pukts".) Equipped with an "annotator", sort of an AI addition to his brain, the narrator learns the Game and comes to Velda to challenge all comers. He puts up a sign saying "I'll beat you the Second Game". And after probing the opponents' weaknesses by playing the first game, he does indeed beat them the second time. He finally draws the attention of Kalin Trobt, a high official and thus a proficient Game player. After the most difficult Game yet, the narrator again prevails, but Trobt perceives that he is a human, and arrests him as a spy.

Veldian society is predicated on exaggerated concepts of honor, and on absolute honesty. So the narrator is simply placed under house arrest at Trobt's house, though he is told that he will die, in the "Final Game". Over the next couple of weeks, the narrator and Trobt become friends, but the narrator's fate remains sealed. Both probe each other for secrets about their respective societies, and in particular a biological reason for much of the Veldian situation is revealed. Finally the narrator comes up with a surprising solution to his problem, and to Velda's problem, and eventually to the Ten Thousand Worlds' problem.

This short novel is a quick, entertaining, and generally absorbing read. It's not quite convincing -- the Game is marginally plausible, but not the narrator's proficiency. The Veldian social structure, and military prowess, both seem rather artificial. I didn't quite buy the biological problem at the heart of Veldian society either. Indeed, Veldqan biology as portrayed seems truly implausible -- I can't believe this race would survive! Other problems were lesser, such as the magical ability of Veldians and Humans to interbreed (this problem could easily have been finessed by a reference to panspermia or a lost colony or something, but instead the Veldians are supposed to be true aliens). Still, overall the story is enjoyable and thoughtful.

I read the novelette "Second Game" and the novel Cosmic Checkmate back to back. It's interesting how closely they resemble each other. The novel is not an extension, but an organic expansion, without even much in the way of added subplots. There is a somewhat unconvincing love interest for the narrator in the novel which is absent in the novelette.* Otherwise the expansions are all fleshed out scenes, added explanations. I think it actually works pretty well -- the novel does not seem padded.

I followed this by reading the 1981 DAW novel, Second Game. This is longer still, and it also features some curious changes. The changes include: changing the planet's name from Velda to Veldq (presumably to make it more "alien", and also perhaps to avoid sounding like a woman's name), changing the narrator's name from Robert O. Lang to Leonard Stromberg (a change I utterly fail to understand unless perhaps that was the original name, and John Campbell insisted on a more Anglo-Saxon lead character), and adding a new social group to Veldq society, the Kismans, low-status merchants. Further changes include more bald exposition of the Ten Thousand Worlds' situation, an altered (and not terribly believable) explanation for the Veldqan level of technology, a hugely expanded subplot about the narrator's Veldqan love interest, including some rather embarrassing sex scenes (and a revised account of the relationship of the sexes on Veldq), and a fair amount of small interpolations, fleshing out details.

On balance I think I prefer the shorter 1962 novel to the 1981 expansion: some of the 1981 additions are sensible fleshing out, but some are silly. The expanded love story is logical and fills in something missing in the 1962 version, but it's not very well done. Other additions, such as the Kismans and the new explanation of Veldqan tech, seem either superfluous or wrong. I wouldn't say, however, that the 1981 version feels padded -- the novelette, in retrospect, seems somewhat rushed, and I would have to say the story basically supports at least 50,000 words.

Finally I went ahead and read the 1991 novelette sequel, by De Vet alone, "Third Game". This is about 15,000 words long. It's set 23 years after the main action of Second Game. There are severe social problems on Veldq, and Leonard Stromberg's half-Veldqan son, Kalin Stromberg, comes to the planet to try to help. After some more harsh evidence of the silly over-violent Veldqan society, and another sometimes embarrassing highly sexed romance, which involved dealing fairly with the oppressed Kisman minority**, and, get this (shades of Asimov's The Stars Like Dust) -- adopt a constitution modelled on the US constitution. It's really a very bad story.

(*There was a curious brief mention of the girl who becomes the narrator's love interest in the novelette -- on reading that, bells went off in my head, and I was surprised that she did not reappear in the story. Which makes me wonder if the novelette wasn't cut before publication, as opposed to the novel being a later expansion.)

(**The Kismans are important in this story as they weren't in the 1981 Second Game, making me wonder if De Vet hadn't already written a version of "Third Game" when he (and MacLean) expanded Cosmic Checkmate to Second Game.)

Birthday Review: Traitor's Gate, by Anne Perry

Anne Perry was born on 28 October 1938 in London, as Juliet Hulme, and the family moved to New Zealand when she was young, for her health. In 1953 she and a close friend murdered the friend's mother (to prevent them moving away), giving her a rather uncommonly appopriate background for a writer of murder mysteries. (This was the subject of Peter Jackson's film Heavenly Creatures.) After serving her time, Hulme changed her name to Anne Perry, and moved to England (and for a time to the United States). She became a Mormon, and as I understand it, two of her novels, the fantasies Tathea and Come, Armageddon, are based on Mormon themes. Her first mystery, The Cater Street Hangman, was published in 1979, and somewhat fortuitously, I discovered her work just a couple of years (and books) later.

She has written novels in several series, most prominent two set in Victorian England: the Thomas and Charlotte Pitt books; and the William Monk/Hester Latterly books. She also wrote several novels about World War I, a whole series of short "Christmas" mysteries, and beginning just last year, books featuring the Pitts' son Daniel. I read the Pitt books and the Monk books with enjoyment for quite a while, but eventually I felt the books were beginning to weaken, and gave up. This review, written over 20 years ago, is of one of the Pitt books that (as you will see) disappointed me. I'm reposting it on the occasion of Perry's 80th birthday.

Review Date: 12 December 1995

TITLE: Traitor`s Gate

AUTHOR: Anne Perry

PUBLISHED: Fawcett Columbine, 1995

ISBN: 0-449-90634-5

This is the latest in Anne Perry`s long series of mystery novels set in late Victorian England (1890, in the present case.) These novels feature Charlotte and Thomas Pitt, he a policeman (just promoted to Superindent), and she an upper-class woman who married shockingly beneath herself, but who maintains a limited entrée to society, useful in helping Thomas with cases involving crimes among the upper class.

Traitor`s Gate features Thomas much more prominently than Charlotte. Thomas` surrogate father, Sir Arthur Desmond, the owner of the estate for which Thomas` actual father was the gamekeeper, has died in his club in London. The death is ruled accidental, or suicide, but his son Matthew, Thomas` close boyhood friend, is convinced it must have been murder, and asks Thomas to investigate.