by Rich Horton

Today is Doris Piserchia's 90th birthday. In honor of that, I'm reposting her first novel, which I reviewed in its Ace Double form long ago. Piserchia was born in West Virginia, and was in the US Navy in the early 1950s. She began publishing SF in the mid-60s, and some of her short fiction gained considerable notice, as did some of her novels, especially the earlier ones. By 1983 thirteen novels and about as many short stories had appeared, two of the novels as by "Curt Selby", but since then she has been silent, apparently as a result of the sudden death of her daughter and her need to raise her grandchild. Here's what I wrote back in 2004:

|

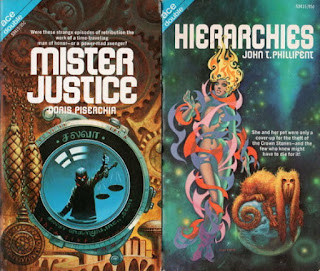

| (Covers by Kelly Freas) |

Hierarchies and Life With Lancelot, both from 1973, are the only two Ace Double halves that Phillifent published under his real name. In the case of Hierarchies, this is probably because the novel was originally serialized in Analog, and most of Phillifent's work for Analog was as Phillifent. In the case of Life With Lancelot, which is an expansion of a "Rackham" story, the best guess is offered by William Barton, who had the novel on the other side of that Ace Double. He noted that he saw some promotional material with the "Rackham" name attached, and he deduced that the eventual attribution to "Phillifent" was a foulup, perhaps caused by Hierarchies appearing at roughly the same time.

The Analog serialization of Hierarchies, in the October and November 1971 issues, is slightly shorter, at some 40,000 words. I did a quick comparison of the two versions, and the changes appear to be small cuts or additions made throughout -- a sentence or two here and there, rather than removing or adding entire scenes. Indeed, the wording changes are extensive, and often quite minor. ("Camouflage" for "hide" is one example.) Perhaps Phillifent did a full rewrite -- or perhaps the Analog editor did a rigorous line edit. (It's not entirely clear who the editor was at the time. The October issue leads with John W. Campbell's obituary. Campbell was still Editor on the masthead, for the November issue as well. More than likely he acquired the story, I would think, but someone else may have done the final editing.)

Hierarchies is a rather light, implausible, short novel. The main character is Rex Sixx (the silly name is eventually explained, and even has a very minor part in the plot), an employee of a security company. Earth has apparently developed a somewhat extensive interstellar society, and now that have contacted the Khandalar system, 6 nations on three planets, which have had a very stagnant hierarchical social order for millennia, apparently having regressed somewhat from a much more technologically advanced society. The Khands are extremely humanoid, differing mainly by being shorter and thinner on average. Rex's security company has been engaged to steal the Crown Stones of Khandalar -- with the connivance of the liberal King-Emperor of one of the nations. It seems that this King-Emperor has realized that his society will be forced to reform along more democratic avenues, and he believes that the Crown Stones, which incorporate some ancient Khandalar tech to allow the King-Emperor to psionically compel obedience, will be a hindrance -- they will be an unavoidable temptation to any King-Emperor faced with democratization.

Rex and his partner Roger are to courier the Crown Stones to Earth. However, to distract attention from the Stones themselves, they have been given an alternate mission -- to ferry a valuable pet to Earth, in the company of a trained keeper. The keeper is Elleen Stame, who turns out surprisingly to be an incredibly beautiful young woman, with a freakishly perfect memory. Rex and Roger both seem to fall for Elleen immediately, despite her ugly voice and her apparent stupidity. The three of them set off for the spaceport, only to be waylaid by brigands, who, it soon becomes clear, were hired by a disaffected member of the Royalty, who does not approve of the King-Emperor's democratic plans. But Rex and Roger have super-suits with extreme defensive ability, so they get away, only to face the rebellious royal again once in space.

The resolution is not of course in doubt, though things do get a bit tough on Rex and Roger and Elleen. The bad guy turns out to be smarter than expected. And, of course, Elleen turns out to have unexpected (even by her) resources. Phillifent also throws in a mild twist or two. It's modestly entertaining light SF adventure for the most part. (Lots of silliness, to be sure, such as the supposedly ultra-reliable security company which nearly gets taken out by bows and arrows.)

Mister Justice is altogether a more ambitious novel, though something of a mess as well. Doris Piserchia had a curious writing career. Born in 1928, she published a story in 1966, but her career began in earnest in 1972 with a couple more stories. Novels began appearing in 1973, and she published novels and stories regularly for the next decade. But (at least according to the ISFDB) nothing has appeared since 1983. She occasionally used the pseudonym "Curt Selby".

Mister Justice opens with several paired scenes, the first in each pair describing a crime that someone gets away with, the second showing, in 2033, appropriate punishment being meted out to the criminals, and photographic proof of the original crime being sent to the authorities. The packets of evidence are signed "Mister Justice". Clearly, "Mister Justice" is a dangerous vigilante -- at the same time, he IS only publishing the obviously guilty, and he seems at least for a time to really reduce crime.

The Secret Service decides to track him down and take him out, led by a mysterious triumvirate, Bailey, Turner, and Burgess. There eventual plan is to recruit a superboy. Daniel is a 12 year old who is sort of coerced by Bailey and co. to train for an eventual search for "Mister Justice" at a special informal school called "SPAC", full of eccentric geniuses. Daniel learns a lot at SPAC, and he also forms an odd relationship with an 11-year old girl called Pala. (Incidentally, I thought this section felt rather Heinleinian.)

Mean time, out in the "real world", society is going to pot. The apparent cause is one gangster who Mister Justice cannot catch -- Arthur Bingle. Bingle sets up a criminal organization that more or less ends up replacing the government, leading to nothing but societal chaos.

Daniel's eventual investigations reveal little enough -- he learns by analyzing the photographs left by Mister Justice which great photographer he is, and from that he manages to deduce that Mister Justice is using time travel to accomplish his deeds. (Something guessable anyway from the initial times of the crime scenes.) Daniel's relationship with Pala progresses, until she is kidnapped. We learn more and more about the time travel aspect of things, and about the decay of society. And we watch Bailey's group spectacularly fail to deal with either Mister Justice or Arthur Bingle.

The novel's resolution is somewhat strange -- basically involving a confrontation between Justice and Bingle. It doesn't really end up anywhere near where the start seemed to promise. There is no real look at the problem of vigilantism. Daniel is introduced as what seems to be the main character, then he sort of fades away (though we do learn what he and Pala are up to by the end). There are odd skips in the book -- at one time 6 years pass from one sentence to the next with no real indication. In many ways I found it a mess. But there is some interest to it. For myself, Daniel and Pala were the most interesting characters, and their eventual fate, a rather traditional SFnal fate, was OK. Some of the secrets of Mister Justice, revealed only obliquely, were satisfying enough. But other aspects didn't work for me. The society shown is not well-drawn, and not plausible in its breakdown either. (And it basically seems like 1970 transported to 2033.) The Bailey and Co. scenes are often pointless. All in all, some good ideas that probably needed another thorough revision to really cohere into a good novel.