I wrote this review way back in 1996, I think for posting at the review forum of one of the very first online bookstores, which name is escaping me now. I'm reposting it today, unchanged, on the 107th anniversary of Brian O'Nolan's birth.

TITLE: The Third Policeman

AUTHOR: Flann O`Brien

PUBLISHER: Plume

ISBN: 0-452-25912-6

This is one of the strangest novels I have ever read. It was written in about 1940, but not published until 1967, a year or two after the author`s death. O`Brien is a pseudonym for the Irish writer Brian O`Nolan, who was also a celebrated newspaper columnist using the name Myles na gCopaleen, the latter name apparently Gaelic. O`Brien`s masterpiece is At Swim-Two-Birds, which was published in 1939. A selection of his "Myles" columns is also well-regarded. However, The Third Policeman is what I saw in the bookstore when I went looking for something by O`Brien, and it wasn`t a bad choice.

This novel is quite funny, quite absurd, and, at bottom, very disturbing. The narrator is a very unpleasant man, who announces in the first sentence "Not everybody knows how I killed old Phillip Mathers, smashing his jaw in with my spade;" not only is he a murderer, but a very lazy man who ruins his family farm, and spends his life researching the works of a madman named De Selby, who believes that, among other things, darkness is an hallucination, the result of accretions of black air. The narrator relates his early life briefly, leading up to his association with another unsavory character, John Divney, who parasitically moves in with the narrator and helps squander his inheritance. Divney and the narrator plot to kill their neighbor, Phillip Mathers, to steal his money. After the murder they decide to leave the money for a while until the coast clears: however they distrust each other so much that they never leave each others company. Finally they go to Mathers`s house to fetch the strongbox with his money: then Divney sends the narrator ahead to the house alone, while he stands lookout, and things get very strange!

The narrator meets Phillip Mathers, acquires a sort of soul which he calls "Joe", and sets out looking for three mysterious policemen. The first two are easily found, and the narrator discusses bicycles, boxes, and other unusual subjects with these policemen. Finally they decide to hang him (for bicycle theft, I think), but he is rescued by the league of one-legged men (the narrator himself has but one leg). He returns to Mathers` house where he encounters the third policeman, and eventually is reunited with John Divney.

The above summary, obviously, does not represent the action or interest of the book at all. The book is full of off-the-wall philosophical speculations, some based on the mad works of De Selby, others original to the policeman (the latter including a theory about bicycles and their riders which has to be read to be appreciated, also a mysterious trip to an underground cavern where anything you can imagine can be created). There are a lot of footnotes discussing De Selby and the controversy surrounding his work: these make the book somewhat reminiscent of Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov (also reminiscent in being the first-person narrative of an insane murderer).

Friday, October 5, 2018

Thursday, October 4, 2018

Old Bestseller: Castle Rackrent, by Maria Edgeworth

Old Bestseller Review: Castle Rackrent, by Maria Edgeworth

a review by Rich Horton

I don't know for sure if this was a "bestseller" -- there were no true bestseller lists in Maria Edgeworth's time. But she was very popular, for realistic contemporary novels like Belinda and Ormond, for children's works, and for satirical works like Castle Rackrent. She was very famous, made a lot of money (more, Wikipedia says, than Jane Austen), was politically influential, and was friends with the likes of Walter Scott and Kitty Pakenham (the Duke of Wellington's wife, and a collateral ancestress of Anthony Powell's wife and thus of the Longfords).

Maria Edgeworth was born in 1768, to an Anglo-Irish father and an English mother. She lived in England until 5, moved to Ireland after he mother's death and her father's remarriage, and later returned to England, but spent much of her life in Ireland (apparently socially much present in both countries). In fact, her political views were much formed by the question of Union between England and Ireland, which she and her father supported, but with doubts because they were well aware how many Irishmen opposed it. Her father, Richard, was a progressive educator, and indeed Maria's first couple of publications were on the subject of education. Richard married 4 times (the second and third being sisters), and had 22 (!) children -- one wag remarked that he had plenty of subjects on whom to try his progressive education theories.

Castle Rackrent was Edgeworth's first "novel", though it is very short -- the main narrative is about 25,000 words, and there are another 7500 or so words of an introduction and a glossary. It was published in 1800. It is sometimes considered the first historical novel, and the first novel to use an unreliable narrator. My edition is the Dover edition.

It is told by one Thady Quirk, who was the steward for four generations of the Rackrent family, who inherited Castle Rackrent from a distant cousin. Thady sings the praises of each of his masters ... Sir Patrick, Sir Murtagh, Sir Kit, and Sir Condy. But we quickly gather that each of them are fairly awful people. Sir Patrick is a spendthrift, and quickly gets into disastrous debt, and then dies. Sir Murtagh is by contrast a miser, and his wife is if anything worse, and his main entertainment is lawsuits against his neighbors. Sir Kit, Murtagh's younger brother, inherits and decides to marry a rich Jewish woman to save the estate, but she won't part with her jewels, and he locks her up for several years in revenge. His gambling and foolishness gets the estate into further trouble -- though Thady's son Jason profits by buying up Rackrent property on the cheap. Finally, Sir Condy has more woman trouble -- throwing over his mistress (Thady's niece) in favor of a rich local woman, whose family hates the Rackrents and thus refuses to give her any dowry. That marriage thus quickly founders, and Condy, after a foolish venture into Parliament, ends up literally drinking himself to death on a bet. And thus ends the Rackrent line.

It's all much more elaborately told of course, in very long paragraphs in Thady's quite plausible sounding Irish voice. There are extensive humorous asides about Irish habits -- these seem at times satirical, and at other times straightforward narrations of real Irish traditions and behaviors (all this much enlarged upon in the Glossary, which is written not in Thady's voice but in that of his "Editor"). As already noted, Thady is an unreliable narrator, and he constantly proclaims his loyalty to and love for the Rackrents, while we can't help but notice that his real interest is in the main chance -- and that in the end one of the primary beneficiaries of the misfortune of the Rackrents is Thady's son.

It's often very funny, though the long paragraphs do drag a bit. And as all the characters are really quite awful people, the novel wears out its welcome fairly quickly -- but as it's very short, that's OK -- it's about as much as we can stand, and pretty entertaining for its length.

a review by Rich Horton

I don't know for sure if this was a "bestseller" -- there were no true bestseller lists in Maria Edgeworth's time. But she was very popular, for realistic contemporary novels like Belinda and Ormond, for children's works, and for satirical works like Castle Rackrent. She was very famous, made a lot of money (more, Wikipedia says, than Jane Austen), was politically influential, and was friends with the likes of Walter Scott and Kitty Pakenham (the Duke of Wellington's wife, and a collateral ancestress of Anthony Powell's wife and thus of the Longfords).

Maria Edgeworth was born in 1768, to an Anglo-Irish father and an English mother. She lived in England until 5, moved to Ireland after he mother's death and her father's remarriage, and later returned to England, but spent much of her life in Ireland (apparently socially much present in both countries). In fact, her political views were much formed by the question of Union between England and Ireland, which she and her father supported, but with doubts because they were well aware how many Irishmen opposed it. Her father, Richard, was a progressive educator, and indeed Maria's first couple of publications were on the subject of education. Richard married 4 times (the second and third being sisters), and had 22 (!) children -- one wag remarked that he had plenty of subjects on whom to try his progressive education theories.

Castle Rackrent was Edgeworth's first "novel", though it is very short -- the main narrative is about 25,000 words, and there are another 7500 or so words of an introduction and a glossary. It was published in 1800. It is sometimes considered the first historical novel, and the first novel to use an unreliable narrator. My edition is the Dover edition.

It is told by one Thady Quirk, who was the steward for four generations of the Rackrent family, who inherited Castle Rackrent from a distant cousin. Thady sings the praises of each of his masters ... Sir Patrick, Sir Murtagh, Sir Kit, and Sir Condy. But we quickly gather that each of them are fairly awful people. Sir Patrick is a spendthrift, and quickly gets into disastrous debt, and then dies. Sir Murtagh is by contrast a miser, and his wife is if anything worse, and his main entertainment is lawsuits against his neighbors. Sir Kit, Murtagh's younger brother, inherits and decides to marry a rich Jewish woman to save the estate, but she won't part with her jewels, and he locks her up for several years in revenge. His gambling and foolishness gets the estate into further trouble -- though Thady's son Jason profits by buying up Rackrent property on the cheap. Finally, Sir Condy has more woman trouble -- throwing over his mistress (Thady's niece) in favor of a rich local woman, whose family hates the Rackrents and thus refuses to give her any dowry. That marriage thus quickly founders, and Condy, after a foolish venture into Parliament, ends up literally drinking himself to death on a bet. And thus ends the Rackrent line.

It's all much more elaborately told of course, in very long paragraphs in Thady's quite plausible sounding Irish voice. There are extensive humorous asides about Irish habits -- these seem at times satirical, and at other times straightforward narrations of real Irish traditions and behaviors (all this much enlarged upon in the Glossary, which is written not in Thady's voice but in that of his "Editor"). As already noted, Thady is an unreliable narrator, and he constantly proclaims his loyalty to and love for the Rackrents, while we can't help but notice that his real interest is in the main chance -- and that in the end one of the primary beneficiaries of the misfortune of the Rackrents is Thady's son.

It's often very funny, though the long paragraphs do drag a bit. And as all the characters are really quite awful people, the novel wears out its welcome fairly quickly -- but as it's very short, that's OK -- it's about as much as we can stand, and pretty entertaining for its length.

Wednesday, October 3, 2018

Belated Birthday Review: Wallace Stevens' Collected Poems

Wallace Stevens was born on October 2, 1979. So, in slightly belated recognition of his birthday, I'm resposting something I wrote for my SFF Net newsgroup a long time ago. I'll caveat by noting that I really don't discuss individual poems in any detail here; and my suggesting that some of the things I wrote are kind of questionable. (Like the bit about him being known in two separate ways.)

I've mentioned before that Wallace Stevens is my favorite poet. (It's possible that I've used qualifiers like "20th Century" and "American" but hang all that, he's my favorite bar none.) Over the past couple of months, I've been engaged in a project, at first sort of offhand, by the end obsessive, of rereading his Collected Poems. And, by the end, of reading his late long poems repeatedly and with particular care.

Stevens is known, it seems to me, in two separate ways. In the popular sense, he is known for a series of remarkable early poems, in most cases not terribly long, notable for striking images and quite beautiful prosody. Of these poems the most famous is surely "Sunday Morning" -- other examples are "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird", "Peter Quince at the Clavier", "Sea Surface Full of Clouds", "Tea at the Palaz of Hoon", "The Emperor of Ice Cream", "The Idea of Order at Key West", "Of Modern Poetry". The great bulk of these come from his first collection, Harmonium, and indeed from the first edition of Harmonium, published in 1923. ("Sea Surface" is from the 1931 reissue and expansion of Harmonium, "The Idea of Order at Key West" is from Ideas of Order (1936), and "Of Modern Poetry" is from Parts of a World (1942).) These were certainly my favorite among his poems. And they remain favorites.

Stevens is known, it seems to me, in two separate ways. In the popular sense, he is known for a series of remarkable early poems, in most cases not terribly long, notable for striking images and quite beautiful prosody. Of these poems the most famous is surely "Sunday Morning" -- other examples are "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird", "Peter Quince at the Clavier", "Sea Surface Full of Clouds", "Tea at the Palaz of Hoon", "The Emperor of Ice Cream", "The Idea of Order at Key West", "Of Modern Poetry". The great bulk of these come from his first collection, Harmonium, and indeed from the first edition of Harmonium, published in 1923. ("Sea Surface" is from the 1931 reissue and expansion of Harmonium, "The Idea of Order at Key West" is from Ideas of Order (1936), and "Of Modern Poetry" is from Parts of a World (1942).) These were certainly my favorite among his poems. And they remain favorites.

But his critical reputation rests strikingly on a completely different set of poems, all later than those mentioned above. (Though it must be acknowledged that at least "Sunday Morning" and "The Idea of Order at Key West" as well as two early long poems, "The Comedian as the Letter C" and "The Monocle de Mon Oncle", are in general highly regarded critically. And that most of his early work is certainly treated with respect.) The longest poem in his Collected Poems is probably the poem with the greatest critical regard, "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction". [Actually, ranking Stevens' poems by "critical regard" is a fools' effort, and I don't think there is any such consensus any more.] This was published as a separate book in 1942, the same year as Parts of a World. ("Notes" isn't actually his longest poem: a controversial poem called "Owl's Clover" was published in two separate forms, both longer than "Notes", but then was basically repudiated by being excluded from the Collected Poems.)

I think it's fair to say that "late Stevens" begins with "Notes", while "early-to-middle Stevens" ends with Parts of a World. ("Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction" was reprinted as part of his 1947 collection Transport to Summer.) Of course the terms "late" and "early" are odd applied to Stevens. His first successful poems appeared in 1915 (including "Sunday Morning"), when he was 36. He was 44 when the first edition of Harmonium came out. That's pretty late for "early"! And by the 1942 publication of "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction" he was 63. Indeed, his production from 1942 through his death in 1955 was remarkable: two major collections each with several long poems (Transport to Summer and The Auroras of Autumn), as well as at least another full collection worth of late poems, some included in the 1954 Collected Poems in a section called "The Rock", and quite a few more not collected until after his death. The other late long poems besides "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction" that attract considerable praise are "Esthétique du Mal" (though this tends also to be disparaged), "Chocorua to its Neighbor", "Credences of Summer", "The Auroras of Autumn", "The Owl in the Sarcophagus", "Things of August", and "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven".

I can only say that my rereading of his poems was remarkably rewarding. Really! (That last "re" was on purpose!) The early favorites remain special -- I dare say I've read "Sunday Morning" hundreds of times, and it seems new every time. "The Idea of Order at Key West" is another long-term favorite. And I was delighted to detect a prefiguring of "The Idea of Order at Key West" in one of my favorite brief poems, "Tea at the Palaz of Hoon". (I knew I couldn't be the only person to have noticed that, and indeed Harold Bloom goes on at some length about the links between the two poems in his book on Stevens.) But the truly eye-opening aspect of this rediscovery was the late long poems. Well, indeed, all the long poems. The early "Comedian" and "Monocle" had never really caught fire for me in earlier readings, but this time they did. I'm still not a huge fan of the popular middle-period long poem "The Man With the Blue Guitar", but I did enjoy this reading. I have long enjoyed a fairly long poem from Parts of a World, "Extracts from Addresses to the Academy of Fine Ideas" -- and I was delighted to see that Harold Bloom also likes that poem. I had earlier approached "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction" with what I can only call trepidation. But on these recent rereadings (four or five careful ones) the poem -- still difficult -- has opened up to me. So too with "The Auroras of Autumn" and the late lovely "pre-elegy" for George Santayana, "To An Old Philosopher in Rome". "Credences of Summer" and "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven" don't yet come clear to me, but reading them is still a pleasure. (I say "come clear" as if I fully understand "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction"! Not likely, but I am sure that each future rereading will show me new things.)

[I should note that on further rereadings, "Credences of Summer" and "To an Old Philosopher in Rome", in particular, have become more important to me.]

What to say about late Stevens? The most obvious adjective is "austere". But that doesn't always apply -- he could also be quite playful. However, there is never the lushness of a "Sunday Morning" or "Sea Surface Full of Clouds" in the late works. The sentences tend to extraordinary length, but the internal rhythms are involving. The poems are all quite philosophical, much concerned with the importance of poetry, the nature of reality versus perceptions of reality, and, perhaps more simply, with growing old. (A Stevens theme, to be sure, that can be traced at least back to "The Monocle de Mon Oncle".)

I also took the time to read two book length studies of Stevens. These are Helen Hennessy Vendler's On Extended Wings: Wallace Stevens' Longer Poems, and Harold Bloom's Wallace Stevens: The Poems of Our Climate. Both are interesting and worthwhile, but also difficult, particularly the Bloom. I think I just don't have the vocabulary or training to always understand Bloom.

(It's interesting to consider the definition of "long poem". By my count there are 18 poems of more than 100 lines in the Collected Poems, and two more ("Owl's Clover" and "The Sail of Ulysses") in Opus Posthumous. But Vendler only explicitly covers 14 poems, including one quite short poem ("Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird", 54 lines). She leaves out one of my favorite longer poems, "Extracts From Address to the Academy of Fine Ideas", and other perhaps less important poems like "Things of August", "The Owl in the Sarcophagus", "Chocorua to its Neighbor" and "A Primitive Like an Orb". But that is just to quibble.)

I've mentioned before that Wallace Stevens is my favorite poet. (It's possible that I've used qualifiers like "20th Century" and "American" but hang all that, he's my favorite bar none.) Over the past couple of months, I've been engaged in a project, at first sort of offhand, by the end obsessive, of rereading his Collected Poems. And, by the end, of reading his late long poems repeatedly and with particular care.

Stevens is known, it seems to me, in two separate ways. In the popular sense, he is known for a series of remarkable early poems, in most cases not terribly long, notable for striking images and quite beautiful prosody. Of these poems the most famous is surely "Sunday Morning" -- other examples are "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird", "Peter Quince at the Clavier", "Sea Surface Full of Clouds", "Tea at the Palaz of Hoon", "The Emperor of Ice Cream", "The Idea of Order at Key West", "Of Modern Poetry". The great bulk of these come from his first collection, Harmonium, and indeed from the first edition of Harmonium, published in 1923. ("Sea Surface" is from the 1931 reissue and expansion of Harmonium, "The Idea of Order at Key West" is from Ideas of Order (1936), and "Of Modern Poetry" is from Parts of a World (1942).) These were certainly my favorite among his poems. And they remain favorites.

Stevens is known, it seems to me, in two separate ways. In the popular sense, he is known for a series of remarkable early poems, in most cases not terribly long, notable for striking images and quite beautiful prosody. Of these poems the most famous is surely "Sunday Morning" -- other examples are "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird", "Peter Quince at the Clavier", "Sea Surface Full of Clouds", "Tea at the Palaz of Hoon", "The Emperor of Ice Cream", "The Idea of Order at Key West", "Of Modern Poetry". The great bulk of these come from his first collection, Harmonium, and indeed from the first edition of Harmonium, published in 1923. ("Sea Surface" is from the 1931 reissue and expansion of Harmonium, "The Idea of Order at Key West" is from Ideas of Order (1936), and "Of Modern Poetry" is from Parts of a World (1942).) These were certainly my favorite among his poems. And they remain favorites.But his critical reputation rests strikingly on a completely different set of poems, all later than those mentioned above. (Though it must be acknowledged that at least "Sunday Morning" and "The Idea of Order at Key West" as well as two early long poems, "The Comedian as the Letter C" and "The Monocle de Mon Oncle", are in general highly regarded critically. And that most of his early work is certainly treated with respect.) The longest poem in his Collected Poems is probably the poem with the greatest critical regard, "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction". [Actually, ranking Stevens' poems by "critical regard" is a fools' effort, and I don't think there is any such consensus any more.] This was published as a separate book in 1942, the same year as Parts of a World. ("Notes" isn't actually his longest poem: a controversial poem called "Owl's Clover" was published in two separate forms, both longer than "Notes", but then was basically repudiated by being excluded from the Collected Poems.)

I think it's fair to say that "late Stevens" begins with "Notes", while "early-to-middle Stevens" ends with Parts of a World. ("Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction" was reprinted as part of his 1947 collection Transport to Summer.) Of course the terms "late" and "early" are odd applied to Stevens. His first successful poems appeared in 1915 (including "Sunday Morning"), when he was 36. He was 44 when the first edition of Harmonium came out. That's pretty late for "early"! And by the 1942 publication of "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction" he was 63. Indeed, his production from 1942 through his death in 1955 was remarkable: two major collections each with several long poems (Transport to Summer and The Auroras of Autumn), as well as at least another full collection worth of late poems, some included in the 1954 Collected Poems in a section called "The Rock", and quite a few more not collected until after his death. The other late long poems besides "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction" that attract considerable praise are "Esthétique du Mal" (though this tends also to be disparaged), "Chocorua to its Neighbor", "Credences of Summer", "The Auroras of Autumn", "The Owl in the Sarcophagus", "Things of August", and "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven".

I can only say that my rereading of his poems was remarkably rewarding. Really! (That last "re" was on purpose!) The early favorites remain special -- I dare say I've read "Sunday Morning" hundreds of times, and it seems new every time. "The Idea of Order at Key West" is another long-term favorite. And I was delighted to detect a prefiguring of "The Idea of Order at Key West" in one of my favorite brief poems, "Tea at the Palaz of Hoon". (I knew I couldn't be the only person to have noticed that, and indeed Harold Bloom goes on at some length about the links between the two poems in his book on Stevens.) But the truly eye-opening aspect of this rediscovery was the late long poems. Well, indeed, all the long poems. The early "Comedian" and "Monocle" had never really caught fire for me in earlier readings, but this time they did. I'm still not a huge fan of the popular middle-period long poem "The Man With the Blue Guitar", but I did enjoy this reading. I have long enjoyed a fairly long poem from Parts of a World, "Extracts from Addresses to the Academy of Fine Ideas" -- and I was delighted to see that Harold Bloom also likes that poem. I had earlier approached "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction" with what I can only call trepidation. But on these recent rereadings (four or five careful ones) the poem -- still difficult -- has opened up to me. So too with "The Auroras of Autumn" and the late lovely "pre-elegy" for George Santayana, "To An Old Philosopher in Rome". "Credences of Summer" and "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven" don't yet come clear to me, but reading them is still a pleasure. (I say "come clear" as if I fully understand "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction"! Not likely, but I am sure that each future rereading will show me new things.)

[I should note that on further rereadings, "Credences of Summer" and "To an Old Philosopher in Rome", in particular, have become more important to me.]

What to say about late Stevens? The most obvious adjective is "austere". But that doesn't always apply -- he could also be quite playful. However, there is never the lushness of a "Sunday Morning" or "Sea Surface Full of Clouds" in the late works. The sentences tend to extraordinary length, but the internal rhythms are involving. The poems are all quite philosophical, much concerned with the importance of poetry, the nature of reality versus perceptions of reality, and, perhaps more simply, with growing old. (A Stevens theme, to be sure, that can be traced at least back to "The Monocle de Mon Oncle".)

I also took the time to read two book length studies of Stevens. These are Helen Hennessy Vendler's On Extended Wings: Wallace Stevens' Longer Poems, and Harold Bloom's Wallace Stevens: The Poems of Our Climate. Both are interesting and worthwhile, but also difficult, particularly the Bloom. I think I just don't have the vocabulary or training to always understand Bloom.

(It's interesting to consider the definition of "long poem". By my count there are 18 poems of more than 100 lines in the Collected Poems, and two more ("Owl's Clover" and "The Sail of Ulysses") in Opus Posthumous. But Vendler only explicitly covers 14 poems, including one quite short poem ("Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird", 54 lines). She leaves out one of my favorite longer poems, "Extracts From Address to the Academy of Fine Ideas", and other perhaps less important poems like "Things of August", "The Owl in the Sarcophagus", "Chocorua to its Neighbor" and "A Primitive Like an Orb". But that is just to quibble.)

Tuesday, October 2, 2018

Birthday Review: A Deepness in the Sky, by Vernor Vinge

Here's a review of arguably Vernor Vinge's most famous novel, and my personal favorite among his works, that I wrote when the book first appeared. Today is Vinge's 74th birthday, so I'm reposting it, in the same format I originally used when I first put it on my then new web page. (That page is now gone.)

Review Date: 28 April 1999

A Deepness in the Sky, by Vernor Vinge

Tor Books, New York, NY, March 1999

$27.95 (US), ISBN: 0-312-85683-0

Review Copyright 1999 by Rich Horton

This is a wonderful SF novel. It's the first novel in a while to really engage me on the sense of wonder level, and to again awaken the feelings of awe and of "I want to be there" that were so central to my early reading of SF. I was complaining earlier about books like Jablokov's Deepdrive, and wondering if the fault lay in me. I mean: that book (Deepdrive) is full of neat ideas, original ideas, and I thought they were well handled, and the story was good. But I never felt fully engaged, never felt "awe". I still suppose the fault may be in my jaded self, but A Deepness in the Sky proves that its still possible to really knock me out SFnally.

I'll briefly summarize the plot, hopefull avoiding spoilers. The book is set perhaps 8000 years in our future. Two starfaring human civilizations reach an anomalous astronomical object at the same time. One of the civilizations is the Qeng Ho, a loosely organized group of traders (reminiscent of Poul Anderson's Kith (this book is dedicated to Anderson) and of Robert A. Heinlein's Traders from Citizen of the Galaxy). The other is called the Emergent civilization (that name is one of many inspired coinages by Vinge). The astronomical object is something called the On/Off star, which shines for only 35 years then is a brown dwarf for the rest of its 250 year period. That's interesting enough, but what draws the two human groups is the presence of radio signals: an alien technological civilization has at last been discovered.

The Emergents turn out to be very authoritarian, and they double-cross the Qeng Ho after having agreed to a cooperative exploration of the planet. However the Qeng Ho fight back, and the humans end up losing interstellar capability. One narrative thread thus follows the human characters as they wait for the On/Off star to ignite, and for the aliens to (with their help) develop a sufficient tech level to rebuild the starships. This thread also shows the Qeng Ho resistance to the Emergent rule. The other main narrative thread follows the Spiders, the arachnoid intelligent natives of the On/Off star's single planet. These beings have long adapted to their sun's peculiarity, by hibernating through the "Dark". But one culture, led by an endearing genius named Sherkaner Underhill, has begun to develop ways of living awake through the Dark time. But they are opposed by suspicious neighbors. And the human watchers begin to subtly interfere. The whole story culminates in a terrifically exciting finish, one which intrigues at the level of action-filled resolution of multiple plots, and also at the level of revelations of the solutions to a number of ingenious scientific puzzles, and thirdly at the level of satisfying emotional thematic resolutions to the journeys of a number of characters. It's uplifting without being unrealistic or mawkish.

There are flaws, though to some extent the flaws are, I would say, necessary. This book is, I think, what Debra Doyle has called a "Romance", as such demanding larger than life characters and events. In this way, the main "flaws" are the somewhat pulpish nature of the plot and characters. But as I hint, I don't find these flaws serious. Indeed, they might really be necessary, indeed virtues, in the context of this sort of book. But it should be said that the plot depends on a few coincidences, and on things like the villains deciding not to kill the good guys because they're not sure the good guys are conspiring against them. (These villains are so bad, I don't see why they wouldn't just figure, "Better safe than sorry!", and kill them anyway (or, in the context of the book, do something worse).) And the characters feature some extremes: most obviously the alien scientist who is just an awesome genius, and who appears at the perfect time in their society. The human characters also include some remarkable folk. And the villains are really really really bad. Gosh, they're bad. But that works, too, because their worst feature is original and scary and believable and a neat SF idea.

Good stuff: with Vinge, I suppose I always think ideas first. He has come up with several. First, his concept of an extended human future in space with strict light-speed limits (as far as anyone in this book knows), is very well-worked out and believable and impressive and fun. It depends on basically three pieces of extrapolation: ramships that can get to about .3c, lifespans extended to about 500 years, and near-perfect suspended animation or coldsleep. The second neat idea is the On/Off star. The idea of a star that shines for 35 or so years and turns off for 210 years is neat, and then giving it a planet and a believable set of aliens is great fun. The aliens are really great fun too: they are too human in how they are presented, but Vinge neatly finesses this issue, in at least a half-convincing way, and he shows us glimpses that suggest real alienness, too. (Include some very nice cultural touches.) The third especially neat idea I won't mention because it might be too much of a spoiler, but the key "tech" of the bad guys is really scary, and a neat SFnal idea. And handled very well, and subtly.

As I said, I found the plot inspiring as well. This is a very long book, about 600 pages, but I was never bored. Moreover, as Patrick Nielsen Hayden has taken pains to point out, the prose in this book is quite effective. I believe Patrick used some such term as "full throated scientifictional roar". Without necessarily understanding exactly what he meant by that, the prose definitely works for me, and in ways which seem possibly particularly "scientifictional" in nature. One key factor here is names: names of characters, for one thing. Vinge's names of humans: Trixia Bonsol, Rixer Brughel, Tomas Nau, and so on, seem well chosen in several ways: they are recognizably human, and linked to present day languages, but just different enough to seem strange, and they (to my ears) sound good. His alien names are also fairly poetic, and both different and familiar sounding. (They are explicitly human coinages: a key point.) Thus: Sherkaner Underhill, Victory Smith, Hrunkner Unnerby. Mileage may vary, but I really liked these names. They certainly beat unpronounceable names, and names with non-alphabetic characters, and the like. The names of technological devices and future societies are also evocative. Examples from the humans include the Emergent society (a name with a double meaning), the Focus virus, and localizers; one alien example is videomancy.

This book is a "prequel" to Vinge's excellent previous novel A Fire Upon the Deep, but it is readable entirely without knowledge of the other book. However, having read A Fire Upon the Deep does allow the reader of A Deepness in the Sky some additional pleasures (and ironies): in particular, speculation about the true nature of the On/Off star, and about the evolutionary history of the Spiders. Also, a main character of this book was also a significant character in the previous book, and knowledge of this character's fate adds a certain frisson to the events depicted in A Deepness in the Sky.

In summary, this is an outstanding SF novel. It marries clever hard SF ideas, a rousing story, involving characters, and several interleaved, emotionally and intellectually compelling, themes. The themes are fine and fundamental to SF: involving the value of exploration and scientific knowledge, the value of freedom and thesacrifices of freedom, the desirability and costs of the dream of Empire, and the question "What would I give up to be smarter ... better ... more focussed?"

Review Date: 28 April 1999

A Deepness in the Sky, by Vernor Vinge

Tor Books, New York, NY, March 1999

$27.95 (US), ISBN: 0-312-85683-0

Review Copyright 1999 by Rich Horton

This is a wonderful SF novel. It's the first novel in a while to really engage me on the sense of wonder level, and to again awaken the feelings of awe and of "I want to be there" that were so central to my early reading of SF. I was complaining earlier about books like Jablokov's Deepdrive, and wondering if the fault lay in me. I mean: that book (Deepdrive) is full of neat ideas, original ideas, and I thought they were well handled, and the story was good. But I never felt fully engaged, never felt "awe". I still suppose the fault may be in my jaded self, but A Deepness in the Sky proves that its still possible to really knock me out SFnally.

I'll briefly summarize the plot, hopefull avoiding spoilers. The book is set perhaps 8000 years in our future. Two starfaring human civilizations reach an anomalous astronomical object at the same time. One of the civilizations is the Qeng Ho, a loosely organized group of traders (reminiscent of Poul Anderson's Kith (this book is dedicated to Anderson) and of Robert A. Heinlein's Traders from Citizen of the Galaxy). The other is called the Emergent civilization (that name is one of many inspired coinages by Vinge). The astronomical object is something called the On/Off star, which shines for only 35 years then is a brown dwarf for the rest of its 250 year period. That's interesting enough, but what draws the two human groups is the presence of radio signals: an alien technological civilization has at last been discovered.

The Emergents turn out to be very authoritarian, and they double-cross the Qeng Ho after having agreed to a cooperative exploration of the planet. However the Qeng Ho fight back, and the humans end up losing interstellar capability. One narrative thread thus follows the human characters as they wait for the On/Off star to ignite, and for the aliens to (with their help) develop a sufficient tech level to rebuild the starships. This thread also shows the Qeng Ho resistance to the Emergent rule. The other main narrative thread follows the Spiders, the arachnoid intelligent natives of the On/Off star's single planet. These beings have long adapted to their sun's peculiarity, by hibernating through the "Dark". But one culture, led by an endearing genius named Sherkaner Underhill, has begun to develop ways of living awake through the Dark time. But they are opposed by suspicious neighbors. And the human watchers begin to subtly interfere. The whole story culminates in a terrifically exciting finish, one which intrigues at the level of action-filled resolution of multiple plots, and also at the level of revelations of the solutions to a number of ingenious scientific puzzles, and thirdly at the level of satisfying emotional thematic resolutions to the journeys of a number of characters. It's uplifting without being unrealistic or mawkish.

There are flaws, though to some extent the flaws are, I would say, necessary. This book is, I think, what Debra Doyle has called a "Romance", as such demanding larger than life characters and events. In this way, the main "flaws" are the somewhat pulpish nature of the plot and characters. But as I hint, I don't find these flaws serious. Indeed, they might really be necessary, indeed virtues, in the context of this sort of book. But it should be said that the plot depends on a few coincidences, and on things like the villains deciding not to kill the good guys because they're not sure the good guys are conspiring against them. (These villains are so bad, I don't see why they wouldn't just figure, "Better safe than sorry!", and kill them anyway (or, in the context of the book, do something worse).) And the characters feature some extremes: most obviously the alien scientist who is just an awesome genius, and who appears at the perfect time in their society. The human characters also include some remarkable folk. And the villains are really really really bad. Gosh, they're bad. But that works, too, because their worst feature is original and scary and believable and a neat SF idea.

Good stuff: with Vinge, I suppose I always think ideas first. He has come up with several. First, his concept of an extended human future in space with strict light-speed limits (as far as anyone in this book knows), is very well-worked out and believable and impressive and fun. It depends on basically three pieces of extrapolation: ramships that can get to about .3c, lifespans extended to about 500 years, and near-perfect suspended animation or coldsleep. The second neat idea is the On/Off star. The idea of a star that shines for 35 or so years and turns off for 210 years is neat, and then giving it a planet and a believable set of aliens is great fun. The aliens are really great fun too: they are too human in how they are presented, but Vinge neatly finesses this issue, in at least a half-convincing way, and he shows us glimpses that suggest real alienness, too. (Include some very nice cultural touches.) The third especially neat idea I won't mention because it might be too much of a spoiler, but the key "tech" of the bad guys is really scary, and a neat SFnal idea. And handled very well, and subtly.

As I said, I found the plot inspiring as well. This is a very long book, about 600 pages, but I was never bored. Moreover, as Patrick Nielsen Hayden has taken pains to point out, the prose in this book is quite effective. I believe Patrick used some such term as "full throated scientifictional roar". Without necessarily understanding exactly what he meant by that, the prose definitely works for me, and in ways which seem possibly particularly "scientifictional" in nature. One key factor here is names: names of characters, for one thing. Vinge's names of humans: Trixia Bonsol, Rixer Brughel, Tomas Nau, and so on, seem well chosen in several ways: they are recognizably human, and linked to present day languages, but just different enough to seem strange, and they (to my ears) sound good. His alien names are also fairly poetic, and both different and familiar sounding. (They are explicitly human coinages: a key point.) Thus: Sherkaner Underhill, Victory Smith, Hrunkner Unnerby. Mileage may vary, but I really liked these names. They certainly beat unpronounceable names, and names with non-alphabetic characters, and the like. The names of technological devices and future societies are also evocative. Examples from the humans include the Emergent society (a name with a double meaning), the Focus virus, and localizers; one alien example is videomancy.

This book is a "prequel" to Vinge's excellent previous novel A Fire Upon the Deep, but it is readable entirely without knowledge of the other book. However, having read A Fire Upon the Deep does allow the reader of A Deepness in the Sky some additional pleasures (and ironies): in particular, speculation about the true nature of the On/Off star, and about the evolutionary history of the Spiders. Also, a main character of this book was also a significant character in the previous book, and knowledge of this character's fate adds a certain frisson to the events depicted in A Deepness in the Sky.

In summary, this is an outstanding SF novel. It marries clever hard SF ideas, a rousing story, involving characters, and several interleaved, emotionally and intellectually compelling, themes. The themes are fine and fundamental to SF: involving the value of exploration and scientific knowledge, the value of freedom and thesacrifices of freedom, the desirability and costs of the dream of Empire, and the question "What would I give up to be smarter ... better ... more focussed?"

Birthday Review: Rainbows End, by Vernor Vinge

Birthday Review: Rainbows End, by Vernor Vinge

a review by Rich Horton

I wrote this review back in 2006 when the book came out. It won the Hugo for Best Novel the following year, though my sense is that it hasn't lasted in the public imagination the way Vinge's other novels have. Today is Vinge's 74th birthday, so I'm reposting it.

Vernor Vinge is now officially a full-time writer, having retired from his day job as a professor of Computer Science at the University of California at San Diego. So fans hoped his new novel would come more quickly, but in fact it's been 7 years. Oh well, it takes as long as it takes. Rainbows End is certainly worth the wait.

Interestingly, it is set at UCSD, and the main character is a former professor there -- though a poet, not a computer scientist. He is Robert Gu, apparently the leading poet of our time (that would be now). But as of about 20 years from now, he has been in a nursing home for years, with Alzheimer's (or some other form of dementia), and other maladies of old age. But he has been cured -- indeed he has hit the jackpot in the "heavenly minefield" of 21st Century medicine.

Robert's son and daughter-in-law, it turns out, are highly placed individuals on the U.S. side in the Great Powers' continuing war against chaos -- against the possibility of various varieties of WOMD being wielded against the whole world. One other key individual is Alfred Vaz, an Indian intelligence head. He and two of his colleagues from Europe and Japan have uncovered a plot to deliver a "YGBM" virus in a clever fashion. YGBM means "You Gotta Believe Me": that is, mind control. They recruit an helper, who they meet only in virtual space, called the Rabbit, who will assist them in infiltrating the biolabs near UCSD where they suspect the virus is under development. The kicker is that the man behind this project is Vaz himself -- but he, of course, will use this power only for good -- he sees it as the only way to control the bad guys in the world. So he needs to play his colleagues and the Rabbit very carefully. But the Rabbit's abilities in the virtual world are quite remarkable.

Inevitably, Robert Gu, his son and daughter-in-law, and his granddaughter Miri, become enmeshed, without their knowledge, in all this plotting. But the story is only partly about Alfred Vaz's machinations. It's also about Robert coming to terms with his new quasi-youth: his new abilities, such as an interest in electronics, and his terrible losses, such as his ability to write poetry. But he may have lost something else: it seems that in his prior life he was a prime jerk, driving away his wife and all his colleagues with simple nastiness. His son mostly hates him, certainly distrusts him. But has he changed?

All this is SFnally fascinating, very scary. And indeed the novel is interesting in the way that it's not quite clear who the heroes are -- well, no, it is clear: Robert Gu and Juan Orozco and Miri Gu are the heroes. But they have been coopted to work for bad guys. Maybe. Or sort of bad guys. And anyway lots of the story is not about that plotty stuff, but rather about Robert dealing with his new "youth" and his lost poetic talents, and Miri dealing with family issues, and Juan dealing with his own relative poverty and poor education ... in the end, the novel is quite satisfying as a look at pretty believable characters in a somewhat believable alternate future (I can't help but thinking that this future doesn't make sense starting from now, but maybe from 20 years ago ...). And then behind it all lurks a very scary, and only partly resolved, big story about a future balanced between terrorist chaos and even scarier order imposed by mind control. I think this is a surprisingly subtle triumph from one of the field's best pure SF writers.

a review by Rich Horton

I wrote this review back in 2006 when the book came out. It won the Hugo for Best Novel the following year, though my sense is that it hasn't lasted in the public imagination the way Vinge's other novels have. Today is Vinge's 74th birthday, so I'm reposting it.

Vernor Vinge is now officially a full-time writer, having retired from his day job as a professor of Computer Science at the University of California at San Diego. So fans hoped his new novel would come more quickly, but in fact it's been 7 years. Oh well, it takes as long as it takes. Rainbows End is certainly worth the wait.

Interestingly, it is set at UCSD, and the main character is a former professor there -- though a poet, not a computer scientist. He is Robert Gu, apparently the leading poet of our time (that would be now). But as of about 20 years from now, he has been in a nursing home for years, with Alzheimer's (or some other form of dementia), and other maladies of old age. But he has been cured -- indeed he has hit the jackpot in the "heavenly minefield" of 21st Century medicine.

Robert's son and daughter-in-law, it turns out, are highly placed individuals on the U.S. side in the Great Powers' continuing war against chaos -- against the possibility of various varieties of WOMD being wielded against the whole world. One other key individual is Alfred Vaz, an Indian intelligence head. He and two of his colleagues from Europe and Japan have uncovered a plot to deliver a "YGBM" virus in a clever fashion. YGBM means "You Gotta Believe Me": that is, mind control. They recruit an helper, who they meet only in virtual space, called the Rabbit, who will assist them in infiltrating the biolabs near UCSD where they suspect the virus is under development. The kicker is that the man behind this project is Vaz himself -- but he, of course, will use this power only for good -- he sees it as the only way to control the bad guys in the world. So he needs to play his colleagues and the Rabbit very carefully. But the Rabbit's abilities in the virtual world are quite remarkable.

Inevitably, Robert Gu, his son and daughter-in-law, and his granddaughter Miri, become enmeshed, without their knowledge, in all this plotting. But the story is only partly about Alfred Vaz's machinations. It's also about Robert coming to terms with his new quasi-youth: his new abilities, such as an interest in electronics, and his terrible losses, such as his ability to write poetry. But he may have lost something else: it seems that in his prior life he was a prime jerk, driving away his wife and all his colleagues with simple nastiness. His son mostly hates him, certainly distrusts him. But has he changed?

All this is SFnally fascinating, very scary. And indeed the novel is interesting in the way that it's not quite clear who the heroes are -- well, no, it is clear: Robert Gu and Juan Orozco and Miri Gu are the heroes. But they have been coopted to work for bad guys. Maybe. Or sort of bad guys. And anyway lots of the story is not about that plotty stuff, but rather about Robert dealing with his new "youth" and his lost poetic talents, and Miri dealing with family issues, and Juan dealing with his own relative poverty and poor education ... in the end, the novel is quite satisfying as a look at pretty believable characters in a somewhat believable alternate future (I can't help but thinking that this future doesn't make sense starting from now, but maybe from 20 years ago ...). And then behind it all lurks a very scary, and only partly resolved, big story about a future balanced between terrorist chaos and even scarier order imposed by mind control. I think this is a surprisingly subtle triumph from one of the field's best pure SF writers.

Monday, October 1, 2018

A Little Known Ace Double: The Atlantic Abomination, by John Brunner/The Martian Missile, by David Grinnell

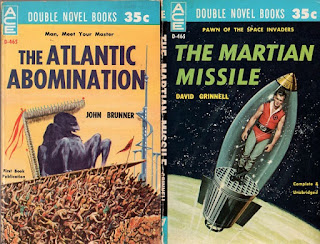

Ace Double Reviews, 65: The Atlantic Abomination, by John Brunner/The Martian Missile, by David Grinnell (#D-465, 1960, $0.35)

I'm reposting this Ace Double review on the occasion of Donald A. Wollheim's birthday: he'd have been 104. Alas, I'm not very nice to his book, but, then, it's not a very good book.

This one qualifies as a rather randomly chosen Ace Double -- on the one hand, I like Brunner, on the other hand, here's an opportunity to review Donald Wollheim (who used "David Grinnell" as a pseudonym for much of his fiction) back to back.

Both of these novels are about 43,000 words long. As far as I know this is the first publication of The Atlantic Abomination in any form, though I may have missed a shorter magazine version under another title. The Martian Missile was first published in 1959 by Thomas Bouregy and Co. Which means some other editor evidently approved of it -- good thing! since I would have been pretty annoyed had Wollheim chosen his own piece of utter garbage! (That other editor would like have been Robert A. W. Lowndes.)

The Atlantic Abomination opens with an alien being panicking as his world seems to be falling apart. We soon gather that Earth, long ago, has been dominated by a few aliens of a species with special telepathic powers. But geological catastrophes are ruining this early human "civilization", and at least one alien escapes to a specially prepared lair.

Fast forward to the 20th Century, and an deep ocean expedition, using special technology to allow exploration of the ocean bed. The explorers happen upon a mysterious installation, which of course is the lair of the evil alien. The rest of the novel is readily enough predicted -- the alien awakes and takes over as many humans as he can. He proceeds to the East Coast of the US and enslaves thousands. An international effort attempts to stop him, with some success, but the alien seems to be figuring things out. Our hero is enslaved, but his new wife (both oceanologists from the original expedition) remains free, but he manages somehow to escape. Does humanity survive? Well of course.

I am being somewhat sarcastic, a bit unfairly. This is certainly nothing special as a novel, but in following its very predictable path, it does entertain. Brunner was just a damn good writer of, for lack of a more precise word, pulp. He always gave value for money. I enjoyed the novel, though I don't think I'll remember it or reread it.

The Martian Missile can also be described as "pulp". 30s pulp. Really BAD 30s pulp. I suppose Wollheim may have written this in 1958 or so, but it sure reads, with its scientific and astronomical stupidities, like it was written in 1931.

A small-time criminal, hiding out in the desert, happens across a crashed alien spaceship. He rescues the alien, only to have the alien implant a bomb or something that will go off in a few years if he doesn't take a special message to the alien's fellows. Naturally he figures that this "message" might mean no good for humanity, but he doesn't see an alternative.

So he sneaks aboard a Russian rocket, and manages to get to the moon. He is able to rendezvous with various planted alien ships, and he proceeds to Mars, Jupiter, and finally to Pluto. Needless to say the description of the conditions on these planets are scientifically ridiculous. Our hero becomes aware of a cosmic battle between good, bad, and indifferent aliens, and he is able to figure out a way to play them off against each other and both save Earth and save his skin.

On the whole this is pretty much SF at its worst. I've read other Wollheim/Grinnell novels, and none of them make me think Wollheim's writing career is anything to be rediscovered, this has to qualify as below his usual standard.

This one qualifies as a rather randomly chosen Ace Double -- on the one hand, I like Brunner, on the other hand, here's an opportunity to review Donald Wollheim (who used "David Grinnell" as a pseudonym for much of his fiction) back to back.

|

| (Covers by Ed Emshwiller and Ed Valigursky) |

The Atlantic Abomination opens with an alien being panicking as his world seems to be falling apart. We soon gather that Earth, long ago, has been dominated by a few aliens of a species with special telepathic powers. But geological catastrophes are ruining this early human "civilization", and at least one alien escapes to a specially prepared lair.

Fast forward to the 20th Century, and an deep ocean expedition, using special technology to allow exploration of the ocean bed. The explorers happen upon a mysterious installation, which of course is the lair of the evil alien. The rest of the novel is readily enough predicted -- the alien awakes and takes over as many humans as he can. He proceeds to the East Coast of the US and enslaves thousands. An international effort attempts to stop him, with some success, but the alien seems to be figuring things out. Our hero is enslaved, but his new wife (both oceanologists from the original expedition) remains free, but he manages somehow to escape. Does humanity survive? Well of course.

I am being somewhat sarcastic, a bit unfairly. This is certainly nothing special as a novel, but in following its very predictable path, it does entertain. Brunner was just a damn good writer of, for lack of a more precise word, pulp. He always gave value for money. I enjoyed the novel, though I don't think I'll remember it or reread it.

The Martian Missile can also be described as "pulp". 30s pulp. Really BAD 30s pulp. I suppose Wollheim may have written this in 1958 or so, but it sure reads, with its scientific and astronomical stupidities, like it was written in 1931.

A small-time criminal, hiding out in the desert, happens across a crashed alien spaceship. He rescues the alien, only to have the alien implant a bomb or something that will go off in a few years if he doesn't take a special message to the alien's fellows. Naturally he figures that this "message" might mean no good for humanity, but he doesn't see an alternative.

So he sneaks aboard a Russian rocket, and manages to get to the moon. He is able to rendezvous with various planted alien ships, and he proceeds to Mars, Jupiter, and finally to Pluto. Needless to say the description of the conditions on these planets are scientifically ridiculous. Our hero becomes aware of a cosmic battle between good, bad, and indifferent aliens, and he is able to figure out a way to play them off against each other and both save Earth and save his skin.

On the whole this is pretty much SF at its worst. I've read other Wollheim/Grinnell novels, and none of them make me think Wollheim's writing career is anything to be rediscovered, this has to qualify as below his usual standard.

Birthday Review: A Princess of Roumania, by Paul Park

Birthday Review: A Princess of Roumania, by Paul Park

a review by Rich Horton

Paul Park turns 64 today, and in honor of his birthday, I'm posting this review I did back in 2005 on SFF Net. As it happens, I reviewed the second and third volumes of the series this novel starts for SF Site. Not the last, though.

Paul Park's A Princess of Roumania, from 2005, is the beginning of his tetralogy also called A Princess of Roumania. In a way this seems a departure for Park, previously the writer of an audacious SF trilogy, The Starbridge Chronicles; a difficult SF novel, Coelestis, and two very religiously-focussed historical novels, The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. None of these books (with the arguable exception of his first trilogy) were terribly commercial. Indeed, none were fantasies, though they are hardly traditional SF, nor traditional historical fiction. By contrast A Princess of Roumania is certainly fantasy, and arguably Young Adult fantasy (the Washington Post compares it (not terribly sensibly) to Harry Potter and Oz); and on the whole I would say it has more commercial potential than his previous books. But in so saying I do not mean to say it is less ambitious than his earlier works, or less imaginative -- indeed, it is a very fine novel, and promises to open a fascinating series.

Paul Park's A Princess of Roumania, from 2005, is the beginning of his tetralogy also called A Princess of Roumania. In a way this seems a departure for Park, previously the writer of an audacious SF trilogy, The Starbridge Chronicles; a difficult SF novel, Coelestis, and two very religiously-focussed historical novels, The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. None of these books (with the arguable exception of his first trilogy) were terribly commercial. Indeed, none were fantasies, though they are hardly traditional SF, nor traditional historical fiction. By contrast A Princess of Roumania is certainly fantasy, and arguably Young Adult fantasy (the Washington Post compares it (not terribly sensibly) to Harry Potter and Oz); and on the whole I would say it has more commercial potential than his previous books. But in so saying I do not mean to say it is less ambitious than his earlier works, or less imaginative -- indeed, it is a very fine novel, and promises to open a fascinating series.

Miranda Popescu is a 15 year old girl in a college town in upstate New York in about the present day. She was adopted from Romania in the chaos following the uprising against Ceausescu. As the novel opens she befriends a lonely one-armed boy, Peter Gross. Her other special friend is a popular girl named Andromeda. Soon they meet a sinister group of teenagers who have just moved to their town, and suddenly their school is set afire, risking Miranda's special keepsakes from Romania: some coins and jewelry, and in particular a remarkable book called The Essential History, which describes world history from an unusual viewpoint.

In a completely different world we meet the Baroness Nicola Ceausescu, formerly a prostitute then a successful actress and dancer, who became the second wife of a much older man. This man was involved in an intrigue which led to the execution of Miranda's father, the exile of her mother to Germany, and the financial ruin of her Aunt, Princess Aegypta Schenk von Schenk, half-German and half a descendant of the White Tyger, Miranda Brancoveanu, who saved Roumania centuries before.

It seems to be Aegypta's hope that Miranda Popescu is the new White Tyger, who will save Roumania from her corrupt current Empress, and from the threat of German invasion. Both Aegypta and Nicola are sorceresses, and Aegypta, we soon gather, has created an artificial world, our world, in which she has hidden Miranda, as well as two loyal retainers, who have been incarnated as Peter and Andromeda.

Nicola has managed to send some people to that world, to find Miranda and bring her back -- both realize that if she is the new White Tyger, control of this teenager will be critical. Nicola, furthermore, is intriguing with a German envoy, thus betraying both her nominal political ally, the Empress, and of course her longtime enemy, the Princess Aegypta.

Nicola's schemes succeed in a limited manner, and Miranda, Peter, and Andromeda all end up in the "real world": our world, and its creating book, having been destroyed. (Apparently.) But they are marooned in the wilds of America, inhabited mainly by savage refugees from earthquake-shattered England. Nicola, however, loses control of her plans, and is forced to turn against her erstwhile German friends, though she does come into possession of a powerful gem, Kepler's Eye, a tourmaline. (It is surely significant that volume II of the series is called The Tourmaline.) She finds herself accused of a murder she didn't commit, while racked with guilt over a murder she did commit. Miranda, in dream contact with Aegypta, a woman she doesn't know, struggles to make her way with Peter, Andromeda, and an obsessed tool of Nicola's, Major Raevsky, to Albany and eventually to a ship to Roumania. Or, she hopes, perhaps back to "our" world. The German Elector of Ratisbon, an illegal sorcerer himself, is trying to find Miranda, and also the tourmaline.

It's a thoroughly interesting novel. In particular, the characters of the villains are wonderfully realized, especially Nicola Ceausescu, who is a certainly a bad person, but at the same time a person with whom we sympathize: and someone who is sometimes on the "right" side. The magical parts are very original, believable (in context), and impressive. There is no real resolution -- this is after all the first of a tetralogy. But I'll be eagerly reading on.

a review by Rich Horton

Paul Park turns 64 today, and in honor of his birthday, I'm posting this review I did back in 2005 on SFF Net. As it happens, I reviewed the second and third volumes of the series this novel starts for SF Site. Not the last, though.

Paul Park's A Princess of Roumania, from 2005, is the beginning of his tetralogy also called A Princess of Roumania. In a way this seems a departure for Park, previously the writer of an audacious SF trilogy, The Starbridge Chronicles; a difficult SF novel, Coelestis, and two very religiously-focussed historical novels, The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. None of these books (with the arguable exception of his first trilogy) were terribly commercial. Indeed, none were fantasies, though they are hardly traditional SF, nor traditional historical fiction. By contrast A Princess of Roumania is certainly fantasy, and arguably Young Adult fantasy (the Washington Post compares it (not terribly sensibly) to Harry Potter and Oz); and on the whole I would say it has more commercial potential than his previous books. But in so saying I do not mean to say it is less ambitious than his earlier works, or less imaginative -- indeed, it is a very fine novel, and promises to open a fascinating series.

Paul Park's A Princess of Roumania, from 2005, is the beginning of his tetralogy also called A Princess of Roumania. In a way this seems a departure for Park, previously the writer of an audacious SF trilogy, The Starbridge Chronicles; a difficult SF novel, Coelestis, and two very religiously-focussed historical novels, The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. None of these books (with the arguable exception of his first trilogy) were terribly commercial. Indeed, none were fantasies, though they are hardly traditional SF, nor traditional historical fiction. By contrast A Princess of Roumania is certainly fantasy, and arguably Young Adult fantasy (the Washington Post compares it (not terribly sensibly) to Harry Potter and Oz); and on the whole I would say it has more commercial potential than his previous books. But in so saying I do not mean to say it is less ambitious than his earlier works, or less imaginative -- indeed, it is a very fine novel, and promises to open a fascinating series.Miranda Popescu is a 15 year old girl in a college town in upstate New York in about the present day. She was adopted from Romania in the chaos following the uprising against Ceausescu. As the novel opens she befriends a lonely one-armed boy, Peter Gross. Her other special friend is a popular girl named Andromeda. Soon they meet a sinister group of teenagers who have just moved to their town, and suddenly their school is set afire, risking Miranda's special keepsakes from Romania: some coins and jewelry, and in particular a remarkable book called The Essential History, which describes world history from an unusual viewpoint.

In a completely different world we meet the Baroness Nicola Ceausescu, formerly a prostitute then a successful actress and dancer, who became the second wife of a much older man. This man was involved in an intrigue which led to the execution of Miranda's father, the exile of her mother to Germany, and the financial ruin of her Aunt, Princess Aegypta Schenk von Schenk, half-German and half a descendant of the White Tyger, Miranda Brancoveanu, who saved Roumania centuries before.

It seems to be Aegypta's hope that Miranda Popescu is the new White Tyger, who will save Roumania from her corrupt current Empress, and from the threat of German invasion. Both Aegypta and Nicola are sorceresses, and Aegypta, we soon gather, has created an artificial world, our world, in which she has hidden Miranda, as well as two loyal retainers, who have been incarnated as Peter and Andromeda.

Nicola has managed to send some people to that world, to find Miranda and bring her back -- both realize that if she is the new White Tyger, control of this teenager will be critical. Nicola, furthermore, is intriguing with a German envoy, thus betraying both her nominal political ally, the Empress, and of course her longtime enemy, the Princess Aegypta.

Nicola's schemes succeed in a limited manner, and Miranda, Peter, and Andromeda all end up in the "real world": our world, and its creating book, having been destroyed. (Apparently.) But they are marooned in the wilds of America, inhabited mainly by savage refugees from earthquake-shattered England. Nicola, however, loses control of her plans, and is forced to turn against her erstwhile German friends, though she does come into possession of a powerful gem, Kepler's Eye, a tourmaline. (It is surely significant that volume II of the series is called The Tourmaline.) She finds herself accused of a murder she didn't commit, while racked with guilt over a murder she did commit. Miranda, in dream contact with Aegypta, a woman she doesn't know, struggles to make her way with Peter, Andromeda, and an obsessed tool of Nicola's, Major Raevsky, to Albany and eventually to a ship to Roumania. Or, she hopes, perhaps back to "our" world. The German Elector of Ratisbon, an illegal sorcerer himself, is trying to find Miranda, and also the tourmaline.

It's a thoroughly interesting novel. In particular, the characters of the villains are wonderfully realized, especially Nicola Ceausescu, who is a certainly a bad person, but at the same time a person with whom we sympathize: and someone who is sometimes on the "right" side. The magical parts are very original, believable (in context), and impressive. There is no real resolution -- this is after all the first of a tetralogy. But I'll be eagerly reading on.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)