I thought I should mention that my new book is out, The Year's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy, 2016 Edition. It's always fun to see the book in print, and to celebrate a whole bunch of great stories.

I dedicated this book to my late father, John Richard (Dick) Horton.

Apropos of that, I recently put together a spreadsheet detailing all the contributors to my books over the past 11 years. This series began in 2006 as two books: Science Fiction: The Best of the Year, 2006 Edition; and Fantasy: The Best of the Year, 2006 Edition. There were three years in that format, and in 2009 we switched to the bigger combined format, with both SF and Fantasy. (I should note that each edition -- 2006, 2016, whatever -- collects stories from the previous year.)

So here's this year's cover:

So, as I said, I put together a combined spreadsheet, of 11 years of these book. One of the things I was interested in was how many times I published new writers -- that is, writers whom I hadn't previously published in this series. I confess, I was partly motivated to investigate this because of an accusation by Eric Raymond that I kept choosing authors from the same pool. That seemed on the face of it blatantly false -- I've always prided myself in choosing a lot of unfamiliar writers. Naturally I have favorites, and there are some writers who appear over and over again (most obviously, Robert Reed, though he's not in this year's book!) But I had a feeling I always included a lot of new (to me) voices.

And I think the statistics back me up. Bottom line -- 62% of the stories in all my books combined were by writers who were appearing first in that year's book. But that's distorted, because of course for the first few years most of the writers were, by default, firsts. The numbers seem to settle in around 50% new writers each year beginning in about 2011 -- the percentages from 2011 through 2016 are 54%, 43%, 61%, 49%, 29%, 53%, 62%. The cumulative total percentage since 2011 is 48% new writers.

So, about half the writers in a typical book of mine have never before appeared in one of my Best of the Year collections. That seems pretty good! And, in fact, a quick comparison with at least one other editor suggests that my percentage of writers new to me is significantly higher. (Which isn't to say the other books aren't also excellent -- they are!)

One more set of numbers: I have published 354 stories by 219 writers over the 11 years of this series. 143 of those writers have appeared in my books only once. The writers who have appeared most are Robert Reed (10), Elizabeth Bear (6), Kelly Link (6), Theodora Goss (6), C. S. E. Cooney (5), Yoon Ha Lee (5), Holly Phillips (5), Genevieve Valentine (5), Rachel Swirsky (5), and Peter Watts (5). (Some of these totals might be slightly affected by how I treated collaborations.)

Tuesday, June 14, 2016

Thursday, June 9, 2016

The Only Novel by a Great Playwright: Lord Malquist and Mr. Moon, by Tom Stoppard

The Only Novel by a Great Playwright: Lord Malquist and Mr. Moon, by Tom Stoppard

a review by Rich Horton

Something a bit different this week -- a fairly little known though probably not forgotten novel by a great great writer -- but a writer known for his plays. This is something I wrote some years ago, a rather brief review, but I like the novel, and Stoppard is such a great writer I thought it worth bringing one of his more obscure works a bit of attention while I finish my latest true "Old Bestseller". (I should perhaps add that K. A. Laity discussed this in a Friday's Forgotten Books post some half-dozen years ago.)

Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Czechoslovakia in 1937. His Jewish family fled Czechoslovakia as the Nazis invaded, ending up in Singapore, then India. His father was killed in a Japanese attack or perhaps as a prisoner of war, and after the war, his mother remarried an Englishman, Kenneth Stoppard. He became a journalist at age 17, fortuitously becoming a theatre critic soon after, which lead to an ambition to write plays, He wrote some radio dramas in the '50s, and his first stage play was completed in 1960. He wrote the first version of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead with the help of a Ford Foundation grant in 1964, and it was first produced in 1966, making him a star. He has written many many plays since then, and also translated many, written some screenplays including work on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Empire of the Sun, Brazil, and Shakespeare in Love.

And one novel, very early in his career (1966): Lord Malquist and Mr. Moon. I've read Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, The Real Thing, Arcadia, The Real Inspector Hound, and a few more plays. I've seen a television version of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, but never seen a Stoppard play live, which I'll have to fix sometime. I've really enjoyed every play I've read by him.

Stoppard's plays are known for virtuoso word play, and this is a feature of Lord Malquist and Mr. Moon as well. (Add Stoppard to the list of English-language writers who grew up hearing another language (Czech, in his case) and who write flashy or otherwise special English prose. (Others: Conrad, Nabokov, Rushdie.)) The story is told mostly from the viewpoint of Mr. Moon, a rather hapless young man in London in 1965 (at the time of Churchill's funeral). He hopes to write a histoy of the world, but isn't making much progress and needs the money, so he takes a job as a professional "Boswell" to Lord Malquist, who desperately wants something to be named after him, in the manner of the Earl of Sandwich or the Duke of Wellington, or MacAdam. Malquist wants Moon to record his bon mots, and indeed Malquist's speech is quite witty.

Mr. Moon has a rich wife, who refuses his sexual overtures, but seems to give herself to pretty much anyone else, and who seems to be running their house as a sort of brothel, for which purpose she has engaged a pretty French maid. Into this mix are thrown Malquist's alcoholic wife, his black Jewish coachman, and an Irishman who claims to be the Risen Christ. Oh, and a lion, and a bomb. It's very funny, though very blackly so, and all is resolved quite inevitably. I really enjoyed it. It does seem though, that with the nearly simultaneous success of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Stoppard abandoned novel-writing for plays -- apparently a good decision!, though I for one would enjoy seeing more novels from him as well as the plays.

a review by Rich Horton

Something a bit different this week -- a fairly little known though probably not forgotten novel by a great great writer -- but a writer known for his plays. This is something I wrote some years ago, a rather brief review, but I like the novel, and Stoppard is such a great writer I thought it worth bringing one of his more obscure works a bit of attention while I finish my latest true "Old Bestseller". (I should perhaps add that K. A. Laity discussed this in a Friday's Forgotten Books post some half-dozen years ago.)

Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Czechoslovakia in 1937. His Jewish family fled Czechoslovakia as the Nazis invaded, ending up in Singapore, then India. His father was killed in a Japanese attack or perhaps as a prisoner of war, and after the war, his mother remarried an Englishman, Kenneth Stoppard. He became a journalist at age 17, fortuitously becoming a theatre critic soon after, which lead to an ambition to write plays, He wrote some radio dramas in the '50s, and his first stage play was completed in 1960. He wrote the first version of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead with the help of a Ford Foundation grant in 1964, and it was first produced in 1966, making him a star. He has written many many plays since then, and also translated many, written some screenplays including work on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Empire of the Sun, Brazil, and Shakespeare in Love.

And one novel, very early in his career (1966): Lord Malquist and Mr. Moon. I've read Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, The Real Thing, Arcadia, The Real Inspector Hound, and a few more plays. I've seen a television version of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, but never seen a Stoppard play live, which I'll have to fix sometime. I've really enjoyed every play I've read by him.

Stoppard's plays are known for virtuoso word play, and this is a feature of Lord Malquist and Mr. Moon as well. (Add Stoppard to the list of English-language writers who grew up hearing another language (Czech, in his case) and who write flashy or otherwise special English prose. (Others: Conrad, Nabokov, Rushdie.)) The story is told mostly from the viewpoint of Mr. Moon, a rather hapless young man in London in 1965 (at the time of Churchill's funeral). He hopes to write a histoy of the world, but isn't making much progress and needs the money, so he takes a job as a professional "Boswell" to Lord Malquist, who desperately wants something to be named after him, in the manner of the Earl of Sandwich or the Duke of Wellington, or MacAdam. Malquist wants Moon to record his bon mots, and indeed Malquist's speech is quite witty.

Mr. Moon has a rich wife, who refuses his sexual overtures, but seems to give herself to pretty much anyone else, and who seems to be running their house as a sort of brothel, for which purpose she has engaged a pretty French maid. Into this mix are thrown Malquist's alcoholic wife, his black Jewish coachman, and an Irishman who claims to be the Risen Christ. Oh, and a lion, and a bomb. It's very funny, though very blackly so, and all is resolved quite inevitably. I really enjoyed it. It does seem though, that with the nearly simultaneous success of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Stoppard abandoned novel-writing for plays -- apparently a good decision!, though I for one would enjoy seeing more novels from him as well as the plays.

Thursday, June 2, 2016

An Old Ace Double: The Ultimate Weapon/The Planeteers, by John W. Campbell

Ace Double Reviews, 97: The Ultimate Weapon, by John W. Campbell/The Planeteers, by John W. Campbell (#G-585, 1966, 50 cents)

a review by Rich Horton

Here's another Ace Double featuring an extremely significant figure in SF history. John W. Campbell, Jr. (1910-1971) was born in New Jersey, and lived there most of his life. He attended MIT (getting to know Norbert Wiener) but finished his degree (a B. S. in Physics, the same degree I hold) at Duke in 1932. (At Duke Campbell met J. B. Rhine and apparently participated as a subject in Rhine's ESP studies -- an interesting fact given Campbell's later obsession with parapsychology.) In 1930 he began publishing SF with several stories in Amazing. Early in his career he was known for stories of super-science. He also published a number of quieter and more thoughtful stories as by "Don A. Stuart", including the classics "Twilight" and "Who Goes There?". In 1937 he became the editor of Astounding Stories, and he is probably the most significant editor in the history of SF. It would be fair to say that he moved SF away from his "John W. Campbell" writing persona and toward his "Don A. Stuart" writing persona, though of course that's an oversimplification. He died in the saddle, as it were, in 1971.

After taking over Astounding Campbell essentially ceased writing fiction. His last published story as an active writer came in 1939, with perhaps the exception of "The Idealists", which appeared in the 1954 Raymond J. Healy original anthology 9 Tales of Time and Space (thanks to John Boston for alerting me to that story, which I think I'll have to seek out). There were a number of pieces written in the 30s but published later, such as The Incredible Planet (1949), and perhaps most interestingly, "All", published in 1976 in a collection called The Space Beyond -- but twice rewritten by major SF writers: as Empire by Clifford Simak, and as Sixth Column by Robert A. Heinlein.

I have quite enjoyed most of the Don A. Stuart stories I've read, and I've been much less impressed by the Campbell stories. This book represents my first fairly extended look at him in that mode.

I have quite enjoyed most of the Don A. Stuart stories I've read, and I've been much less impressed by the Campbell stories. This book represents my first fairly extended look at him in that mode.

The Ultimate Machine is actually a longish novella, a somewhat typical size for an Ace Double half at about 31,000 words. It was first published in the October and December 1936 issues of Amazing Stories as "Uncertainty". As it happens, I saw a copy -- may have bought a copy -- of one of Sol Cohen's horrible reprint magazines shortly after I started buying SF magazines: the July 1974 issue of Science Fiction Adventure Classics, which reprints "Uncertainty" in full.

It opens with an Earth scout ship out near Pluto, where they detect an alien ship with very powerful weapons, that easily overwhelms the mines on Pluto and destroys a couple of ships. Buck Kendall, a rich man and great scientist/engineer who has enlisted in the Space Navy, is one who escapes, and he immediately raises the alert. But his Navy bosses ignore him, brushing off what he saw as human space pirates, so he resigns, goes back to private industry, and arranges for some funding from the only smart man in the Navy, Commander McLaurin, to set up a lab on the Moon and start working on better weapons. He has deduced that the aliens are from Mira, and that they will be back at Earth in two years.

We switch to the viewpoint of the alien commander, Gresth Gkae. His race are looking for a stable system to take over, because Mira is a variable star. His ship is one of many assigned to look for new planets, and having found the Sol System he races back to Mira, to organize and then lead an invasion force.

The rest of the story is easy to figure out. Kendall and his cohorts put together some amazing new weapons and ships in an impossibly short time -- the aliens return and are surprised at the resistance they find, but they still seem likely to prevail, until Kendall figures out a way to use the Uncertainty Theory as the Ultimate Weapon. The conclusion is a slight twist, helped by a ridiculous deus ex machina.

All that said, I liked a fair amount of the story. Except for the stupidity about the Uncertainty Theory, the scientific inventions are at least on the border of plausibility (well, across the border, but at least backed by actual 1930s physics) -- Campbell mentions, for example, a weapon much like the neutron bomb. You can kind of see him working the direction he would ask his authors to take at Astounding.

The Planeteers is a collection of 5 stories about Ted Penton and Rod Blake. The stories are:

"The Brain Stealers of Mars" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1936) 8300 words

"The Double Minds" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1937) 11500 words

"The Immortality Seekers" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1937) 11700 words

"The Tenth World" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1937) 10100 words

"The Brain Pirates" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1938) 7400 words

Penton and Blake have invented atomic power, which is illegal on Earth. (Due to an accident that took out 300 square miles of Europe.) Exiled, they fly their atomic powered ship, which no on can match, all over the Solar System, looking to get rich. They keep encountering strange and intelligent aliens who always turn out to have their own interests that run counter to Penton and Blake's. Penton is the smart guy, Blake the foil.

In "Brain Stealers of Mars", they encounter creatures on Mars that can exactly mimic other creatures, and end up having to decide which of a dozen or so copies of Penton and Blake are the true ones. In "The Double Minds", a race on Callisto that has learned to use the two halves of their brain separately, increasing their mind power but reducing their coordination, has enslaved another Callistan race. Penton and Blake help out the revolution, with unexpected consequences. In "The Immortality Seekers", set on Europa, a fairly benign race turns out to need the Beryllium from which Penton and Blake's ship is made to assist what seems to be nanotech in making them immortal. Another clever creature is enlisted to help Penton and Blake. Then they head out beyond Pluto, to the Tenth World, very cold but inhabited by a very intelligent energy eater that can't control its urges to grab energy from anything hotter. Finally, on the moon of the Tenth World, surprisingly warm compared to its primary!, they encounter a creature that can eat almost anything.

These are silly and kind of annoying stories. The science -- mostly on purpose, to be sure -- is just too stupid, and the supposedly comic interactions of Penton and Blake came off pretty flat too me. Very minor work. Campbell surely made the right decision switching to the editor's seat.

a review by Rich Horton

Here's another Ace Double featuring an extremely significant figure in SF history. John W. Campbell, Jr. (1910-1971) was born in New Jersey, and lived there most of his life. He attended MIT (getting to know Norbert Wiener) but finished his degree (a B. S. in Physics, the same degree I hold) at Duke in 1932. (At Duke Campbell met J. B. Rhine and apparently participated as a subject in Rhine's ESP studies -- an interesting fact given Campbell's later obsession with parapsychology.) In 1930 he began publishing SF with several stories in Amazing. Early in his career he was known for stories of super-science. He also published a number of quieter and more thoughtful stories as by "Don A. Stuart", including the classics "Twilight" and "Who Goes There?". In 1937 he became the editor of Astounding Stories, and he is probably the most significant editor in the history of SF. It would be fair to say that he moved SF away from his "John W. Campbell" writing persona and toward his "Don A. Stuart" writing persona, though of course that's an oversimplification. He died in the saddle, as it were, in 1971.

After taking over Astounding Campbell essentially ceased writing fiction. His last published story as an active writer came in 1939, with perhaps the exception of "The Idealists", which appeared in the 1954 Raymond J. Healy original anthology 9 Tales of Time and Space (thanks to John Boston for alerting me to that story, which I think I'll have to seek out). There were a number of pieces written in the 30s but published later, such as The Incredible Planet (1949), and perhaps most interestingly, "All", published in 1976 in a collection called The Space Beyond -- but twice rewritten by major SF writers: as Empire by Clifford Simak, and as Sixth Column by Robert A. Heinlein.

I have quite enjoyed most of the Don A. Stuart stories I've read, and I've been much less impressed by the Campbell stories. This book represents my first fairly extended look at him in that mode.

I have quite enjoyed most of the Don A. Stuart stories I've read, and I've been much less impressed by the Campbell stories. This book represents my first fairly extended look at him in that mode.The Ultimate Machine is actually a longish novella, a somewhat typical size for an Ace Double half at about 31,000 words. It was first published in the October and December 1936 issues of Amazing Stories as "Uncertainty". As it happens, I saw a copy -- may have bought a copy -- of one of Sol Cohen's horrible reprint magazines shortly after I started buying SF magazines: the July 1974 issue of Science Fiction Adventure Classics, which reprints "Uncertainty" in full.

It opens with an Earth scout ship out near Pluto, where they detect an alien ship with very powerful weapons, that easily overwhelms the mines on Pluto and destroys a couple of ships. Buck Kendall, a rich man and great scientist/engineer who has enlisted in the Space Navy, is one who escapes, and he immediately raises the alert. But his Navy bosses ignore him, brushing off what he saw as human space pirates, so he resigns, goes back to private industry, and arranges for some funding from the only smart man in the Navy, Commander McLaurin, to set up a lab on the Moon and start working on better weapons. He has deduced that the aliens are from Mira, and that they will be back at Earth in two years.

We switch to the viewpoint of the alien commander, Gresth Gkae. His race are looking for a stable system to take over, because Mira is a variable star. His ship is one of many assigned to look for new planets, and having found the Sol System he races back to Mira, to organize and then lead an invasion force.

The rest of the story is easy to figure out. Kendall and his cohorts put together some amazing new weapons and ships in an impossibly short time -- the aliens return and are surprised at the resistance they find, but they still seem likely to prevail, until Kendall figures out a way to use the Uncertainty Theory as the Ultimate Weapon. The conclusion is a slight twist, helped by a ridiculous deus ex machina.

All that said, I liked a fair amount of the story. Except for the stupidity about the Uncertainty Theory, the scientific inventions are at least on the border of plausibility (well, across the border, but at least backed by actual 1930s physics) -- Campbell mentions, for example, a weapon much like the neutron bomb. You can kind of see him working the direction he would ask his authors to take at Astounding.

The Planeteers is a collection of 5 stories about Ted Penton and Rod Blake. The stories are:

"The Brain Stealers of Mars" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1936) 8300 words

"The Double Minds" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1937) 11500 words

"The Immortality Seekers" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1937) 11700 words

"The Tenth World" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1937) 10100 words

"The Brain Pirates" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1938) 7400 words

Penton and Blake have invented atomic power, which is illegal on Earth. (Due to an accident that took out 300 square miles of Europe.) Exiled, they fly their atomic powered ship, which no on can match, all over the Solar System, looking to get rich. They keep encountering strange and intelligent aliens who always turn out to have their own interests that run counter to Penton and Blake's. Penton is the smart guy, Blake the foil.

In "Brain Stealers of Mars", they encounter creatures on Mars that can exactly mimic other creatures, and end up having to decide which of a dozen or so copies of Penton and Blake are the true ones. In "The Double Minds", a race on Callisto that has learned to use the two halves of their brain separately, increasing their mind power but reducing their coordination, has enslaved another Callistan race. Penton and Blake help out the revolution, with unexpected consequences. In "The Immortality Seekers", set on Europa, a fairly benign race turns out to need the Beryllium from which Penton and Blake's ship is made to assist what seems to be nanotech in making them immortal. Another clever creature is enlisted to help Penton and Blake. Then they head out beyond Pluto, to the Tenth World, very cold but inhabited by a very intelligent energy eater that can't control its urges to grab energy from anything hotter. Finally, on the moon of the Tenth World, surprisingly warm compared to its primary!, they encounter a creature that can eat almost anything.

These are silly and kind of annoying stories. The science -- mostly on purpose, to be sure -- is just too stupid, and the supposedly comic interactions of Penton and Blake came off pretty flat too me. Very minor work. Campbell surely made the right decision switching to the editor's seat.

Thursday, May 26, 2016

Old "good" seller: Coronation Summer, by Angela Thirkell

Old Bestseller: Coronation Summer, by Angela Thirkell

a review by Rich Horton

I don't think Angela Thirkell was ever really a bestseller but her books, it appears, sold steadily over the years, in a career that last from about 1930 to her death in 1961. She still has a strong coterie of fans -- indeed, the Angela Thirkell Society will have a convention in Kansas City this year just the week before the World Science Fiction Convention.

She was born in 1890, the daughter of John Mackail and Margaret Burne-Jones, thus Rudyard Kipling's first cousin once removed, and Edward Burne-Jones' granddaughter. J. M. Barrie was her godfather. Her brother Dennis was also a novelist. Angela Mackail married James McInnes in 1911, and had three children with him befor divorcing him. (He was bisexual, and an adulterer.) She married again in 1918, to George Thirkell, a Tasmanian man, and the couple moved to Australia. But Thirkell hated it there, and left Thirkell in 1929, taking her son Lance and returning to England. Perhaps because she need the money, she began to write (she had done some journalism in Australia), and her first novel appeared in 1931. Some 40 books followed until her death (the last completed by another hand). The great majority of her books were set, curiously, in Barsetshire, the fictional county invented by the 19th Century novelist Anthony Trollope. Thirkell's books were contemporary, imagining Barsetshire as it would have been in the '30s-'50s. Many of her books, especially the later ones, were fairly conventional romances in plot structure. But as far as I can tell, her virtues were never plot, but instead a cheerfully satirical view of her characters and their milieu, and a great ear for dialogue.

The book I chose (partly simply because it was the book I encountered) is not quite characteristic of her work. Coronation Summer is an historical novel, set in 1838 when Queen Victoria was crowned. It was first published by the Oxford University Press, presumably reflecting the novel's rather educational aspect. It was reprinted in 1953 by her usual publishers, Hamish Hamilton in England and Alfred A. Knopf in the US. (My copy is the latter.)

The book I chose (partly simply because it was the book I encountered) is not quite characteristic of her work. Coronation Summer is an historical novel, set in 1838 when Queen Victoria was crowned. It was first published by the Oxford University Press, presumably reflecting the novel's rather educational aspect. It was reprinted in 1953 by her usual publishers, Hamish Hamilton in England and Alfred A. Knopf in the US. (My copy is the latter.)

Part of the book is sort of a travelogue and description of London life in 1838. Period illustrations are included: things like reprints of opera tickets. And there are numerous events: the Coronation, of course, but also a canoe race, a ceremony at Eton called Eton Montem, an opera, dress buying, and the occasional party.

There's a plot, too, if a fairly thin one. The story is presented as Mrs. Fan Darnley, as of 1840, writing up her memories of her summer in London the year of the Coronation, 1838. It opens with her and her soon-to-be sister-in-law, Emily Dacre, opening a book intended for Fanny's husband Henry Darnley. The book is Ingoldsby's Legends, and they wonder if the author, Thomas Ingoldsby, is the same Tom Ingoldsby whom they met in London. (Ingoldsby's Legends is a real book, once quite famous, though there was no Tom Ingoldsby -- that was a pseudonym.) Fan decides to write about her and Emily's visit to London.

In London they meet a couple of eligible men -- Mr. Vavasour, a rather pretentious author; and Henry (Hal) Darnley, a friend of Fan's brother Ned from his time at Cambridge. Hal and Ned are in London partly to prepare for a race. As we know from the beginning of the book that Fan's married name is Darnley, there's not a ton of suspense (not that there would have been -- in the way of romance novels it's pretty obvious from the start that Mr. Vavasour is not a suitable candidate). Meanwhile, Emily and Ned fall quickly in love. The two young women spend the next few weeks seeing what they can in London, while Fan's father, Mr. Harcourt, risks his family's solvency by gambling. Fan shows some interest in Mr. Vavasour, but really from the start she clearly prefers Hal Darnley. They meet a number of famous people, including the novelist Benjamin Disraeli (well, he's a politician too!) and the controversial poetess Caroline Norton, of who Fan cannot approve as she has left her husband. (This was a scandalous case in 1830s London, eventually leading, through Norton's efforts, to improvements in the rights of women in cases of divorce, especially as to custody of their children. Her husband was a bad person, abusive and financially reckless, so she was widely sympathized with.) Anyway, things come to a head at the end with Hal Darnley apparently convinced that Fan prefers Mr. Vavasour, and with Mr. Harcourt ruined (and Mrs. Harcourt, back home, on her deathbed). But all is resolved happily (largely because Hal Darnley is a very rich man).

In reality, then, the plot is of minor interest, and the sort of travelogue aspect is, while somewhat interest, not really that fascinating. But the book is still great fun -- why? The dialogue, and the portrayal of the characters. It's quite funny throughout. Mr. Harcourt (Fan and Ned's father) is very amusing: a blowhard of sorts, generous to a fault while pretending to be close with his money, a reflexive and unthinking Tory who hates Frenchmen especially. Fan is a bit of a prig and thus is always disapproving of Emily, who is slightly more relaxed, and Fan's exasperation with Emily is delightfully portrayed.

Coronation Summer is a short novel, and a slight one, but it's really rather delightful in sum. I'm not sure I'll get around to any of Thirkell's Barsetshire novels, but I'm quite sure I'd enjoy them if I tried them.

a review by Rich Horton

I don't think Angela Thirkell was ever really a bestseller but her books, it appears, sold steadily over the years, in a career that last from about 1930 to her death in 1961. She still has a strong coterie of fans -- indeed, the Angela Thirkell Society will have a convention in Kansas City this year just the week before the World Science Fiction Convention.

She was born in 1890, the daughter of John Mackail and Margaret Burne-Jones, thus Rudyard Kipling's first cousin once removed, and Edward Burne-Jones' granddaughter. J. M. Barrie was her godfather. Her brother Dennis was also a novelist. Angela Mackail married James McInnes in 1911, and had three children with him befor divorcing him. (He was bisexual, and an adulterer.) She married again in 1918, to George Thirkell, a Tasmanian man, and the couple moved to Australia. But Thirkell hated it there, and left Thirkell in 1929, taking her son Lance and returning to England. Perhaps because she need the money, she began to write (she had done some journalism in Australia), and her first novel appeared in 1931. Some 40 books followed until her death (the last completed by another hand). The great majority of her books were set, curiously, in Barsetshire, the fictional county invented by the 19th Century novelist Anthony Trollope. Thirkell's books were contemporary, imagining Barsetshire as it would have been in the '30s-'50s. Many of her books, especially the later ones, were fairly conventional romances in plot structure. But as far as I can tell, her virtues were never plot, but instead a cheerfully satirical view of her characters and their milieu, and a great ear for dialogue.

The book I chose (partly simply because it was the book I encountered) is not quite characteristic of her work. Coronation Summer is an historical novel, set in 1838 when Queen Victoria was crowned. It was first published by the Oxford University Press, presumably reflecting the novel's rather educational aspect. It was reprinted in 1953 by her usual publishers, Hamish Hamilton in England and Alfred A. Knopf in the US. (My copy is the latter.)

The book I chose (partly simply because it was the book I encountered) is not quite characteristic of her work. Coronation Summer is an historical novel, set in 1838 when Queen Victoria was crowned. It was first published by the Oxford University Press, presumably reflecting the novel's rather educational aspect. It was reprinted in 1953 by her usual publishers, Hamish Hamilton in England and Alfred A. Knopf in the US. (My copy is the latter.)Part of the book is sort of a travelogue and description of London life in 1838. Period illustrations are included: things like reprints of opera tickets. And there are numerous events: the Coronation, of course, but also a canoe race, a ceremony at Eton called Eton Montem, an opera, dress buying, and the occasional party.

There's a plot, too, if a fairly thin one. The story is presented as Mrs. Fan Darnley, as of 1840, writing up her memories of her summer in London the year of the Coronation, 1838. It opens with her and her soon-to-be sister-in-law, Emily Dacre, opening a book intended for Fanny's husband Henry Darnley. The book is Ingoldsby's Legends, and they wonder if the author, Thomas Ingoldsby, is the same Tom Ingoldsby whom they met in London. (Ingoldsby's Legends is a real book, once quite famous, though there was no Tom Ingoldsby -- that was a pseudonym.) Fan decides to write about her and Emily's visit to London.

In London they meet a couple of eligible men -- Mr. Vavasour, a rather pretentious author; and Henry (Hal) Darnley, a friend of Fan's brother Ned from his time at Cambridge. Hal and Ned are in London partly to prepare for a race. As we know from the beginning of the book that Fan's married name is Darnley, there's not a ton of suspense (not that there would have been -- in the way of romance novels it's pretty obvious from the start that Mr. Vavasour is not a suitable candidate). Meanwhile, Emily and Ned fall quickly in love. The two young women spend the next few weeks seeing what they can in London, while Fan's father, Mr. Harcourt, risks his family's solvency by gambling. Fan shows some interest in Mr. Vavasour, but really from the start she clearly prefers Hal Darnley. They meet a number of famous people, including the novelist Benjamin Disraeli (well, he's a politician too!) and the controversial poetess Caroline Norton, of who Fan cannot approve as she has left her husband. (This was a scandalous case in 1830s London, eventually leading, through Norton's efforts, to improvements in the rights of women in cases of divorce, especially as to custody of their children. Her husband was a bad person, abusive and financially reckless, so she was widely sympathized with.) Anyway, things come to a head at the end with Hal Darnley apparently convinced that Fan prefers Mr. Vavasour, and with Mr. Harcourt ruined (and Mrs. Harcourt, back home, on her deathbed). But all is resolved happily (largely because Hal Darnley is a very rich man).

In reality, then, the plot is of minor interest, and the sort of travelogue aspect is, while somewhat interest, not really that fascinating. But the book is still great fun -- why? The dialogue, and the portrayal of the characters. It's quite funny throughout. Mr. Harcourt (Fan and Ned's father) is very amusing: a blowhard of sorts, generous to a fault while pretending to be close with his money, a reflexive and unthinking Tory who hates Frenchmen especially. Fan is a bit of a prig and thus is always disapproving of Emily, who is slightly more relaxed, and Fan's exasperation with Emily is delightfully portrayed.

Coronation Summer is a short novel, and a slight one, but it's really rather delightful in sum. I'm not sure I'll get around to any of Thirkell's Barsetshire novels, but I'm quite sure I'd enjoy them if I tried them.

Thursday, May 19, 2016

Old Bestseller: Peter, by F. Hopkinson Smith

Old Bestseller: Peter, by F. Hopkinson Smith

a review by Rich Horton

Here's a very true Old Bestseller -- this novel was published in 1908, and was 8th on the Publishers' Weekly list of the top ten sellers of that year, and again 9th in 1909. And the author had the top sellers of 1896 (Tom Grogan) and 1898 (Caleb West). Tom Grogan seems particularly interesting -- about a woman whose husband dies, and who then dresses as a man and does his work in order to keep earning his paycheck.

Francis Hopkinson Smith (1838-1915) was a true polymath. He was a renowned civil engineer (perhaps most famously building the foundation for the Statue of Liberty, and the Race Rock Lighthouse). He was a major artist, noted mostly for landscapes done in charcoal or watercolor. He was a descendant of Francis Hopkinson, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. And of course he was a prolific novelist, writer of multiple bestsellers, beginning with his first successful novel, Col. Carter of Cartersville (1891). He had a reputation as a chronicler of the Old South, but I should note that none of the other bestsellers I mention -- Tom Grogan, Caleb West (about the building of the Race Rock Lighthouse), nor Peter, are particularly about the South. Autobiographical elements did creep regularly into his novels -- as with Caleb West, as already noted. Also, The Fortunes of Oliver Horn deals with the artist life, and portrays versions of a number of Smith's artist colleagues, and a number of Smith's heroes (including the hero of Peter) are natives of Smith's own home state, Maryland.

Peter was first published in 1908 by Charles Scribner's Sons. My edition is also from Scribner's, a 1913 reprint. There are four illustrations by A. I. Keller.

The novel is subtitled: "A Novel of Which He is not the Hero". It opens in New York, with the narrator, or Scribe, called only the Major, coming to Peter Grayson's worksplace, a distinguished old bank, the Exeter. Peter is about 60 years old, a teller. He is a bachelor, and he has a maiden sister, Felicia. The time is late in the 19th Century. The first couple of chapters slowly introduce Peter and his morals -- his belief in honest work, his devotion to his modest job, and the respect he is held in by numerous people. Peter and the narrator make their way to Peter's apartment, where they find an invitation to a party given by the architect Holker Morris for his employees. (It has been suggested that the character Morris was based on the famous architect Stanford White, a friend of Smith's, who had been murdered in 1906 by the husband of Evelyn Nesbit, an actress and one of the Gibson Girl models, who had apparently been seduced by White while only 14 or 16 (her birthdate is in question). I should add that the portrayal of Holker Morris in Peter gives no suggestion of White's scandalous history.) At Morris' party, he awards a prize to Garry Minott, a young star at the firm. Peter, however, is more impressed with Garry Minott's friend, John Breen, and he decides to take an interest in him.

Breen is an orphan, who has been taken in by his uncle, Arthur Breen. John (or "Jack") is working in his uncle's financial firm, but he has become concerned over what he thinks are potentially shady dealings -- nothing illegal, but immoral. The last straw comes when an acquaintance is ruined due to Arthur's maneuverings. Jack is also slightly importuned by Arthur's stepdaughter, Corinne, a vaguely pretty but spoiled girl who seems to regard Jack as her rightful property. And as Jack grows closer to Peter Grayson, he is offended that Corinne -- and Garry Minott, who has begun to see Corinne socially -- seem unimpressed, to the point of rudeness, with the old man. With some subtle prompting by Peter, Jack quits his uncle's establishment, leaves his house, and looks for a job -- eventually finding one with the engineer Henry MacFarlane -- who, as it happens, has a beautiful daughter, Ruth, whom Jack had met and been entranced by at a party given by Peter and his sister Felicia.

The story begins to jump forward, with Jack Breen beginning to do good work for Henry MacFarlane, and beginning to get closer to Ruth. Peter Grayson stays in contact, and so does his sometimes meddling sister Felicia. Ruth and Jack are clearly in love, but Jack's pride stands in the way of marriage. Then a dramatic disaster threatens Henry MacFarlane's life and livelihood, and Jack is instrumental in saving the day. Meanwhile, Garry Minott has married Corinne and started his own business.

Jack and Ruth finally plight their troth, but they need to wait to get married until Jack is financially able. He does have one piece of property, though it is apparently worthless. Arthur Breen also has an interest in a neighboring property. And Garry and Corinne's marriage seems troubled -- Garry is under a great deal of stress. Things come to a head with a melodramatic suicide, and a noble effort by Jack to save his friend, or at least his friend's reputation. Arthur Breen again proves his moral weakness, and also his stupidity -- and Jack is helped at the last minute by an unexpected agent -- Peter Grayson's friend Isaac Cohen, a Jewish tailor. Jack is given a lesson in the wrongness of his reflexive anti-Semitism, but things turn out, in a slightly deus ex machina fashion, quite wonderfully ...

This is by no means a great novel, or even a very good one, but it's not a bad read. There is one point to make -- this book was published 3 years after Edith Wharton's great novel The House of Mirth. Wharton's novel is almost infinitely better -- but it is noticeably accepting of its period's anti-Semitism, and Smith's novel is quite pointedly critical of that attitude. There is another point of connection with The House of Mirth -- each novel features a slightly ambiguous suicide, by the same means (chloral hydrate).

Peter Grayson, as noted in the subtitle, is not officially the "hero" of Peter, but he is the linchpin: a highly moral character, dismissive in particular of those who lust after money. He is a good friend to Isaac Cohen, even as his whole set (including his beloved sister Felicia) automatically reject him due to his religion. Peter is certainly an implausibly saintly character, but he's interesting and someone we like. Ruth and Jack are also implausibly wonderful people, but that's the way this sort of novel goes.

There are noticeable details that reflect Smith's own life. Henry MacFarlane, the engineer, surely resembles that aspect of Smith to a degree. There is a short section discussing artists that seems to comment on Smith's views of art, and his place in the art world. None of this comes off as tendentious -- rather, Smith's clear knowledge of both milieus gives the book a certain believability. Once again, this is a novel that seems quite plausibly a bestseller of its time -- but not a novel that especially demands our attention over a century later.

a review by Rich Horton

Here's a very true Old Bestseller -- this novel was published in 1908, and was 8th on the Publishers' Weekly list of the top ten sellers of that year, and again 9th in 1909. And the author had the top sellers of 1896 (Tom Grogan) and 1898 (Caleb West). Tom Grogan seems particularly interesting -- about a woman whose husband dies, and who then dresses as a man and does his work in order to keep earning his paycheck.

Francis Hopkinson Smith (1838-1915) was a true polymath. He was a renowned civil engineer (perhaps most famously building the foundation for the Statue of Liberty, and the Race Rock Lighthouse). He was a major artist, noted mostly for landscapes done in charcoal or watercolor. He was a descendant of Francis Hopkinson, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. And of course he was a prolific novelist, writer of multiple bestsellers, beginning with his first successful novel, Col. Carter of Cartersville (1891). He had a reputation as a chronicler of the Old South, but I should note that none of the other bestsellers I mention -- Tom Grogan, Caleb West (about the building of the Race Rock Lighthouse), nor Peter, are particularly about the South. Autobiographical elements did creep regularly into his novels -- as with Caleb West, as already noted. Also, The Fortunes of Oliver Horn deals with the artist life, and portrays versions of a number of Smith's artist colleagues, and a number of Smith's heroes (including the hero of Peter) are natives of Smith's own home state, Maryland.

Peter was first published in 1908 by Charles Scribner's Sons. My edition is also from Scribner's, a 1913 reprint. There are four illustrations by A. I. Keller.

The novel is subtitled: "A Novel of Which He is not the Hero". It opens in New York, with the narrator, or Scribe, called only the Major, coming to Peter Grayson's worksplace, a distinguished old bank, the Exeter. Peter is about 60 years old, a teller. He is a bachelor, and he has a maiden sister, Felicia. The time is late in the 19th Century. The first couple of chapters slowly introduce Peter and his morals -- his belief in honest work, his devotion to his modest job, and the respect he is held in by numerous people. Peter and the narrator make their way to Peter's apartment, where they find an invitation to a party given by the architect Holker Morris for his employees. (It has been suggested that the character Morris was based on the famous architect Stanford White, a friend of Smith's, who had been murdered in 1906 by the husband of Evelyn Nesbit, an actress and one of the Gibson Girl models, who had apparently been seduced by White while only 14 or 16 (her birthdate is in question). I should add that the portrayal of Holker Morris in Peter gives no suggestion of White's scandalous history.) At Morris' party, he awards a prize to Garry Minott, a young star at the firm. Peter, however, is more impressed with Garry Minott's friend, John Breen, and he decides to take an interest in him.

Breen is an orphan, who has been taken in by his uncle, Arthur Breen. John (or "Jack") is working in his uncle's financial firm, but he has become concerned over what he thinks are potentially shady dealings -- nothing illegal, but immoral. The last straw comes when an acquaintance is ruined due to Arthur's maneuverings. Jack is also slightly importuned by Arthur's stepdaughter, Corinne, a vaguely pretty but spoiled girl who seems to regard Jack as her rightful property. And as Jack grows closer to Peter Grayson, he is offended that Corinne -- and Garry Minott, who has begun to see Corinne socially -- seem unimpressed, to the point of rudeness, with the old man. With some subtle prompting by Peter, Jack quits his uncle's establishment, leaves his house, and looks for a job -- eventually finding one with the engineer Henry MacFarlane -- who, as it happens, has a beautiful daughter, Ruth, whom Jack had met and been entranced by at a party given by Peter and his sister Felicia.

The story begins to jump forward, with Jack Breen beginning to do good work for Henry MacFarlane, and beginning to get closer to Ruth. Peter Grayson stays in contact, and so does his sometimes meddling sister Felicia. Ruth and Jack are clearly in love, but Jack's pride stands in the way of marriage. Then a dramatic disaster threatens Henry MacFarlane's life and livelihood, and Jack is instrumental in saving the day. Meanwhile, Garry Minott has married Corinne and started his own business.

Jack and Ruth finally plight their troth, but they need to wait to get married until Jack is financially able. He does have one piece of property, though it is apparently worthless. Arthur Breen also has an interest in a neighboring property. And Garry and Corinne's marriage seems troubled -- Garry is under a great deal of stress. Things come to a head with a melodramatic suicide, and a noble effort by Jack to save his friend, or at least his friend's reputation. Arthur Breen again proves his moral weakness, and also his stupidity -- and Jack is helped at the last minute by an unexpected agent -- Peter Grayson's friend Isaac Cohen, a Jewish tailor. Jack is given a lesson in the wrongness of his reflexive anti-Semitism, but things turn out, in a slightly deus ex machina fashion, quite wonderfully ...

This is by no means a great novel, or even a very good one, but it's not a bad read. There is one point to make -- this book was published 3 years after Edith Wharton's great novel The House of Mirth. Wharton's novel is almost infinitely better -- but it is noticeably accepting of its period's anti-Semitism, and Smith's novel is quite pointedly critical of that attitude. There is another point of connection with The House of Mirth -- each novel features a slightly ambiguous suicide, by the same means (chloral hydrate).

Peter Grayson, as noted in the subtitle, is not officially the "hero" of Peter, but he is the linchpin: a highly moral character, dismissive in particular of those who lust after money. He is a good friend to Isaac Cohen, even as his whole set (including his beloved sister Felicia) automatically reject him due to his religion. Peter is certainly an implausibly saintly character, but he's interesting and someone we like. Ruth and Jack are also implausibly wonderful people, but that's the way this sort of novel goes.

There are noticeable details that reflect Smith's own life. Henry MacFarlane, the engineer, surely resembles that aspect of Smith to a degree. There is a short section discussing artists that seems to comment on Smith's views of art, and his place in the art world. None of this comes off as tendentious -- rather, Smith's clear knowledge of both milieus gives the book a certain believability. Once again, this is a novel that seems quite plausibly a bestseller of its time -- but not a novel that especially demands our attention over a century later.

Friday, May 13, 2016

A Couple George MacDonald Books: The Light Princess and The Golden Key

A review by Rich Horton

Looking for a book to cover this week, and not wanting to dip again into my trove of Ace Double reviews, and not quite finished with my latest Old Bestseller, I figured I'd cover a couple of lovely children's fantasies by the great George MacDonald.

George MacDonald (1824-1905) was a Scottish clergyman of the latter part of the 19th Century, rather Universalist in his views, a significant influence on C. S. Lewis (to the extent that Lewis made him a character in The Great Divorce), and the author of several excellent children's fantasies, and some fine work for adults as well. My favorite of his books has long been At the Back of the North Wind. Other fine children's work includes The Princess and the Goblin and The Princess and Curdie (the first of which was made into a (so-so) animated movies a few years ago), and Lilith is a fine adult novel. Phantastes, which I have not read, also has a reputation as a good adult fantasy. As with Lewis, most of his work is at least partly Christian allegory, or at any rate heavily imbued with Christian themes, though MacDonald could be much stranger than Lewis.

In the late 1960s, Maurice Sendak illustrated a couple of shorter MacDonald children's stories (about 10,000 words apiece). These were The Light Princess and The Golden Key. Thus these aren't really forgotten: indeed MacDonald has settled into a fairly established place in the canon of 19th Century religious fantasists. The Light Princess is very light-hearted and funny, while The Golden Key is a mystical and lovely fairy tale.

The Golden Key is the story of two children, a boy and a girl, who live (not together) on the border of Fairyland. The boy has been told that at the end of the rainbow he can find a golden key -- it is not to be sold, and no one knows what door it may open, but it will surely lead somewhere wonderful. One day he sees a rainbow, and decides to follow it into Fairyland, where it seems the end of it might be -- and there he finds the golden key. Meantime, the girl, much mistreated, wanders into the forest of Fairyland, following a strange owl-like flying fish. Soon she meets a beautiful, ageless, woman, and she learns that she and the boy must journey together, looking for the keyhole into which the golden key will fit.

Their journey is long (though the story is short), and quite wonderful. They meet some strange and wise old men, and encounter many beautiful and curious sights. At last, of course, they find the doorway with the keyhole.

The ending is unexpected and quite moving and beautiful.

It is tempting to try to analyze this story -- is it an allegory of marriage? or the story of a joint journey to salvation? Perhaps, though, as W. H. Auden suggests in an essay published as an afterword to this edition, it is best to simply let yourself be absorbed by the story, to enjoy its lovely and haunting images.

The Light Princess is the tale of a princess who is cursed by a mean, jealous, witch so that she has no gravity. The book is full of puns, so MacDonald makes much both of her weightlessness, and the lack of gravity in her character. Naturally her parents are upset and try to have her cured, but to no avail (although the efforts of a couple of Chinese philosophers to provide a cure are rendered amusingly). However the Princess is quite happy with her "light" state (of course it is in her nature to be always happy). In the way of things, a Prince appears, and falls in love with the Princess. Then the witch realizes that her curse has failed to make the Princess unhappy, so she takes further steps, which are thwarted by the selfless behavior of the Prince, and which result in the Princess recovering her gravity: not an unmixed blessing, but one which her new maturity allows her to realize is best in the long run.

This is a delightful story, told with just the right mixture of whimsy and mildly serious moral comment. The characters are lightly and accurately drawn (the Princess` parents and the Chinese philosophers in particular, are delightful), and the story is predictable but still quite imaginative, with a number of nice touches to do with the Princess` weightlessness.

Sunday, May 8, 2016

My first post on the 2016 Hugo Final Ballot

Over at Black Gate I have made a post about the 2016 Hugo Final Ballot, and its problems. This is all fairly familiar ground, mind you. I'm planning another post sometime in the next few months which will review the ballot category by category, with my thoughts on how I'll vote, but that'll have to wait until I read what I haven't read yet.

Anyway, the post is The Hugo Nominations, 2016; or, Sigh ...

Anyway, the post is The Hugo Nominations, 2016; or, Sigh ...

Thursday, May 5, 2016

Another Ace Double: Empire of the Atom, by A. E. Van Vogt/Space Station #1, by Frank Belknap Long

Ace Double Reviews, 96: Empire of the Atom, by A. E. Van Vogt/Space Station #1, by Frank Belknap Long (#D-242, 1957, 35 cents)

a review by Rich Horton

Both authors of this Ace Double are fairly significant -- Van Vogt of course is a legend, and an SFWA Grand Master. Long is less prominent, but he did win a World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement, and he has -- or had -- a significant reputation as a Horror writer, and a disciple of H. P. Lovecraft. Both were also very long-lived.

A. E. Van Vogt was born in 1912 in Canada, and died in 2000. He worked for the Canadian Ministry of Defence, doing some writing on the side, beginning with true confessions stories, and turning to SF in 1938, inspired by John Campbell's classic "Who Goes There?". His first sale, to Campbell at Astounding, was "Black Destroyer", still considered a classic. He made a huge splash in 1940 with the Astounding serial Slan, and another splash with "The Weapon Shop" (1942), which was fixed up into a novel, The Weapon Shops of Isher. (The term "fix-up" was, I believe, a Van Vogt coinage.) His most famous novel is probably still The World of Null-A (serialized in Astounding in 1945). He became a full-time writer in the early '40s, and moved to California in 1944. He was an early adopter of L. Ron Hubbard's Dianetics (later Scientology), though he apparently left the movement around 1961.

A. E. Van Vogt was born in 1912 in Canada, and died in 2000. He worked for the Canadian Ministry of Defence, doing some writing on the side, beginning with true confessions stories, and turning to SF in 1938, inspired by John Campbell's classic "Who Goes There?". His first sale, to Campbell at Astounding, was "Black Destroyer", still considered a classic. He made a huge splash in 1940 with the Astounding serial Slan, and another splash with "The Weapon Shop" (1942), which was fixed up into a novel, The Weapon Shops of Isher. (The term "fix-up" was, I believe, a Van Vogt coinage.) His most famous novel is probably still The World of Null-A (serialized in Astounding in 1945). He became a full-time writer in the early '40s, and moved to California in 1944. He was an early adopter of L. Ron Hubbard's Dianetics (later Scientology), though he apparently left the movement around 1961.

There is no denying Van Vogt's immense importance and influence in the field of SF, and I certainly don't dispute that he deserved the Grand Master award. But I confess I've never much liked his work. By and large I agree with the points Damon Knight made in his famous essay on The World of Null-A. I've generally found Van Vogt's work illogical, not very well-written, downright slapdash on occasion. But a lot of people I truly respect really love his work, so I admit without reservation that I am missing something important. Sometimes that's the way it is.

So I approached Empire of the Atom with some caution. It is another "fix-up", though a fairly coherent one, comprising five novelettes first published in Astounding in 1946 and 1947. It was published in hardcover by Shasta in 1957, followed the same year by this abridged Ace Double edition. (It's still fairly long for an Ace Double at some 56,000 words.)

I have to say I was pleasantly surprised by the book: I quite enjoyed it. One reason is that the plot is more controlled, more logical, than in other Van Vogt books, only veering off in a Van Vogtian direction right at the end. There's a reason for that -- I realized immediately that his had to be a retelling of some portion of Imperial Roman history, but my knowledge of that history was not sufficient for me to recognize the exact correspondences. But Wikipedia helped immediately -- the story is based on the life of the Emperor Claudius, most specifically as portrayed by Robert Graves in I, Claudius. This anchoring in actual historical events, I feel, kept Van Vogt on course, as it were.

It is set some 10,000 years in the future, after humans have colonized the planets of the Solar System, and then been reduced to barbarism on each of these worlds. A city-state, Linn, arose, and in the recent past it conquered the world and began to try to annex the barbarians on Venus, Mars, and even outer satellites such as Europa. The ruler, or Lord Leader, is a vigorous man but getting older. A new child is born to his scheming second wife, Lydia. (These are, of course, analogues to Augustus and Livia.) The new baby, named Clane, turns out to be a mutant -- Lydia was accidentally exposed to radiation -- this society uses radioactive metals (and worships the "Atom Gods") but has no idea how they work. As a mutant Clane should be killed. However, a leading Temple Scientist wants to raise him and show that mutants, if treated properly, have the same potential as anyone. So Clane is raised, somewhat isolated, and becomes an unusual but very intelligent young man.

The succeeding episodes show Clane learning how to function amidst his scheming relatives, the worst of whom is Lydia, whose prime desire is to place her son by a previous marriage, Lord Tews, on the throne. Clane has no wish to rule, but he does wish Linn to do well, and he does have relative favorites among his relatives, and so he helps one of his Uncles to win a great triumph on Mars, only to have the maneuvering of Livia and Lord Tews mess things up. The dueling continues, as a rebellion on Venus is also crushed, as Clane makes some significant discoveries, and as Tews finally achieves his goals, only to be threatened by an unexpected barbarian incursion from Europa -- a crisis that at last forces Clane to the forefront. Here at the denouement the book finally takes its Van Vogtian turn, but I actually found that aspect kind of cool. There is a sequel, The Wizard of Linn, serialized in Astounding in 1950.

Frank Belknap Long (1901-1994) began publishing in 1920 and his 1921 story "The Eye Above the Mantel" attracted Lovecraft's attention. He published quite a lot of horror-tinged fiction in the next couple of decades, contributing to Weird Tales from its first year (1923). His most famous story might be "The Hounds of Tindalos". He also wrote a fair amount of SF, and he wrote in several other genres (including comics, some Ellery Queen stories, a Man From Uncle story, and Gothics).

I first encountered Long with the Doubleday collection The Early Long, from the mid-'70s, part of a number of books that followed Isaac Asimov's The Early Asimov, in featuring early stories by well-known SF writers along with extensive material about the early careers of these writers. Even then I thought Long a curious choice for such an anthology, and I admit I've felt that way more and more as time goes by -- I've been very unimpressed by everything I've read from him. But I must admit that his reputation in the Horror field is actually pretty good -- I'm not really a Horror reader, so I must defer to those who really love that genre, and especially those who love Lovecraft. The most interesting SF story I've read by Long is "Lake of Fire" (Planet Stories, May 1951), not because it's all that good, but because it is a very direct prefiguring of Roger Zelazny's "A Rose for Ecclesiastes".

Space Station #1 is some 55,000 words long. This appears to be its first publication (and it may be Long's first novel-length fiction). It opens with a certain Lieutenant David Corriston in a desperate fight for his life in the bowels of the title Space Station. It turns out that this fight is the result of a murder he had witnessed just a few minutes earlier, and perhaps more to the point, of his conversation with Helen Ramsey, the daughter of Stephen Ramsey, who controls the uranium mining on Mars, apparently by oppressing the colonists. There follows a somewhat wild sequence of events, as Corriston meets Helen, the two fall instantly and implausibly in love, Helen's bodyguard is killed, she disappears, Corriston barely survives his fight, a uranium freighter coming to the station suddenly loses control and veers to the surface of Earth in a terrible disaster, Corriston is imprisoned by the station's Captain, he discovers that a number of people, including Helen and the Captain, are wearing very sophisticated masks ...

For several chapters I found this quite entertaining, but somewhere along the way it went wildly off the rails. It devolves into a silly and implausible (but of course!) battle for the soul of Mars, as Corriston must convince the Martians that neither the oppressor Stephen Ramsey nor the thug they have hired to oppose him are worth respecting ... only, it turns out, Ramsey sort of his (if mainly for having a wonderful daughter) ... And Corriston proves his worth by trekking across Mars and beating up a guy and etc. etc.

It really reads like Long started writing and every so often lost his way and just hared off in a new direction until he had written a novel's worth of words and then resolved things. The hero gets the girl, the villain(s) are vanquished, and, oh, by the way, at the last second he introduces Martian lampreys just because he needed to extend things a few thousand words more. Oh well.

a review by Rich Horton

Both authors of this Ace Double are fairly significant -- Van Vogt of course is a legend, and an SFWA Grand Master. Long is less prominent, but he did win a World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement, and he has -- or had -- a significant reputation as a Horror writer, and a disciple of H. P. Lovecraft. Both were also very long-lived.

A. E. Van Vogt was born in 1912 in Canada, and died in 2000. He worked for the Canadian Ministry of Defence, doing some writing on the side, beginning with true confessions stories, and turning to SF in 1938, inspired by John Campbell's classic "Who Goes There?". His first sale, to Campbell at Astounding, was "Black Destroyer", still considered a classic. He made a huge splash in 1940 with the Astounding serial Slan, and another splash with "The Weapon Shop" (1942), which was fixed up into a novel, The Weapon Shops of Isher. (The term "fix-up" was, I believe, a Van Vogt coinage.) His most famous novel is probably still The World of Null-A (serialized in Astounding in 1945). He became a full-time writer in the early '40s, and moved to California in 1944. He was an early adopter of L. Ron Hubbard's Dianetics (later Scientology), though he apparently left the movement around 1961.

A. E. Van Vogt was born in 1912 in Canada, and died in 2000. He worked for the Canadian Ministry of Defence, doing some writing on the side, beginning with true confessions stories, and turning to SF in 1938, inspired by John Campbell's classic "Who Goes There?". His first sale, to Campbell at Astounding, was "Black Destroyer", still considered a classic. He made a huge splash in 1940 with the Astounding serial Slan, and another splash with "The Weapon Shop" (1942), which was fixed up into a novel, The Weapon Shops of Isher. (The term "fix-up" was, I believe, a Van Vogt coinage.) His most famous novel is probably still The World of Null-A (serialized in Astounding in 1945). He became a full-time writer in the early '40s, and moved to California in 1944. He was an early adopter of L. Ron Hubbard's Dianetics (later Scientology), though he apparently left the movement around 1961.There is no denying Van Vogt's immense importance and influence in the field of SF, and I certainly don't dispute that he deserved the Grand Master award. But I confess I've never much liked his work. By and large I agree with the points Damon Knight made in his famous essay on The World of Null-A. I've generally found Van Vogt's work illogical, not very well-written, downright slapdash on occasion. But a lot of people I truly respect really love his work, so I admit without reservation that I am missing something important. Sometimes that's the way it is.

So I approached Empire of the Atom with some caution. It is another "fix-up", though a fairly coherent one, comprising five novelettes first published in Astounding in 1946 and 1947. It was published in hardcover by Shasta in 1957, followed the same year by this abridged Ace Double edition. (It's still fairly long for an Ace Double at some 56,000 words.)

I have to say I was pleasantly surprised by the book: I quite enjoyed it. One reason is that the plot is more controlled, more logical, than in other Van Vogt books, only veering off in a Van Vogtian direction right at the end. There's a reason for that -- I realized immediately that his had to be a retelling of some portion of Imperial Roman history, but my knowledge of that history was not sufficient for me to recognize the exact correspondences. But Wikipedia helped immediately -- the story is based on the life of the Emperor Claudius, most specifically as portrayed by Robert Graves in I, Claudius. This anchoring in actual historical events, I feel, kept Van Vogt on course, as it were.

It is set some 10,000 years in the future, after humans have colonized the planets of the Solar System, and then been reduced to barbarism on each of these worlds. A city-state, Linn, arose, and in the recent past it conquered the world and began to try to annex the barbarians on Venus, Mars, and even outer satellites such as Europa. The ruler, or Lord Leader, is a vigorous man but getting older. A new child is born to his scheming second wife, Lydia. (These are, of course, analogues to Augustus and Livia.) The new baby, named Clane, turns out to be a mutant -- Lydia was accidentally exposed to radiation -- this society uses radioactive metals (and worships the "Atom Gods") but has no idea how they work. As a mutant Clane should be killed. However, a leading Temple Scientist wants to raise him and show that mutants, if treated properly, have the same potential as anyone. So Clane is raised, somewhat isolated, and becomes an unusual but very intelligent young man.

The succeeding episodes show Clane learning how to function amidst his scheming relatives, the worst of whom is Lydia, whose prime desire is to place her son by a previous marriage, Lord Tews, on the throne. Clane has no wish to rule, but he does wish Linn to do well, and he does have relative favorites among his relatives, and so he helps one of his Uncles to win a great triumph on Mars, only to have the maneuvering of Livia and Lord Tews mess things up. The dueling continues, as a rebellion on Venus is also crushed, as Clane makes some significant discoveries, and as Tews finally achieves his goals, only to be threatened by an unexpected barbarian incursion from Europa -- a crisis that at last forces Clane to the forefront. Here at the denouement the book finally takes its Van Vogtian turn, but I actually found that aspect kind of cool. There is a sequel, The Wizard of Linn, serialized in Astounding in 1950.

Frank Belknap Long (1901-1994) began publishing in 1920 and his 1921 story "The Eye Above the Mantel" attracted Lovecraft's attention. He published quite a lot of horror-tinged fiction in the next couple of decades, contributing to Weird Tales from its first year (1923). His most famous story might be "The Hounds of Tindalos". He also wrote a fair amount of SF, and he wrote in several other genres (including comics, some Ellery Queen stories, a Man From Uncle story, and Gothics).

I first encountered Long with the Doubleday collection The Early Long, from the mid-'70s, part of a number of books that followed Isaac Asimov's The Early Asimov, in featuring early stories by well-known SF writers along with extensive material about the early careers of these writers. Even then I thought Long a curious choice for such an anthology, and I admit I've felt that way more and more as time goes by -- I've been very unimpressed by everything I've read from him. But I must admit that his reputation in the Horror field is actually pretty good -- I'm not really a Horror reader, so I must defer to those who really love that genre, and especially those who love Lovecraft. The most interesting SF story I've read by Long is "Lake of Fire" (Planet Stories, May 1951), not because it's all that good, but because it is a very direct prefiguring of Roger Zelazny's "A Rose for Ecclesiastes".

Space Station #1 is some 55,000 words long. This appears to be its first publication (and it may be Long's first novel-length fiction). It opens with a certain Lieutenant David Corriston in a desperate fight for his life in the bowels of the title Space Station. It turns out that this fight is the result of a murder he had witnessed just a few minutes earlier, and perhaps more to the point, of his conversation with Helen Ramsey, the daughter of Stephen Ramsey, who controls the uranium mining on Mars, apparently by oppressing the colonists. There follows a somewhat wild sequence of events, as Corriston meets Helen, the two fall instantly and implausibly in love, Helen's bodyguard is killed, she disappears, Corriston barely survives his fight, a uranium freighter coming to the station suddenly loses control and veers to the surface of Earth in a terrible disaster, Corriston is imprisoned by the station's Captain, he discovers that a number of people, including Helen and the Captain, are wearing very sophisticated masks ...

For several chapters I found this quite entertaining, but somewhere along the way it went wildly off the rails. It devolves into a silly and implausible (but of course!) battle for the soul of Mars, as Corriston must convince the Martians that neither the oppressor Stephen Ramsey nor the thug they have hired to oppose him are worth respecting ... only, it turns out, Ramsey sort of his (if mainly for having a wonderful daughter) ... And Corriston proves his worth by trekking across Mars and beating up a guy and etc. etc.

It really reads like Long started writing and every so often lost his way and just hared off in a new direction until he had written a novel's worth of words and then resolved things. The hero gets the girl, the villain(s) are vanquished, and, oh, by the way, at the last second he introduces Martian lampreys just because he needed to extend things a few thousand words more. Oh well.

Friday, April 29, 2016

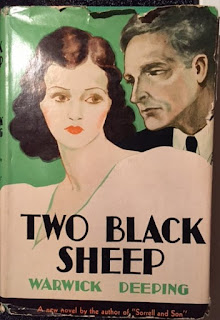

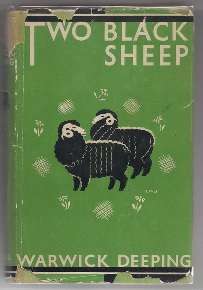

Old Bestseller: Two Black Sheep, by Warwick Deeping

Old Bestseller: Two Black Sheep, by Warwick

Deeping

A review by Rich Horton

I knew, when I started to write about old

bestsellers from the early 20th Century, that sooner or later I

would cover a Warwick Deeping book, but I have to confess that I could never

get interested in the copies I saw of his most famous novel, Sorrell and Son (1925), even though it’s

marginally Science Fiction. So I waited until I came across another novel – Two Black Sheep, from 1933. My edition

is from Grosset and Dunlap. There is a curious note on the dust jacket: "The issuance of this new edition at a reduced price is made possible by a) use of the same plates made for the original edition, and b) the author's acceptance of a reduced royalty". The "reduced price" was 75 cents! As noted, the dust jacket, and the binding, indicate Grosset and Dunlap. However, the reuse of plates from the original edition extends to an internal designation as "A Borzoi Book, Alfred E. Knopf", and the copyright page says "Published September 8, 1933. First two printings before publication. Third Printing, September 1933.", which must also be from a Knopf printing. This does suggest it sold fairly well. The G&D edition must have been not too much later, as the back page listing of other Deeping novels shows none later than Two Black Sheep.

The first UK edition was from Cassell’s,

earlier in 1933, and the novel was serialized (as “Black Sheep, Black Sheep”) between

September 1932 and February 1933 in the Hearst magazine International-Cosmopolitan. There was apparently a movie version, called Two Sinners.

Warwick

Deeping (1877-1950) was an English writer, originally a Doctor (apparently

following in the footsteps of his father). He began publishing novels in 1903,

but continued in his practice for some time. He served in the Royal Medical

Corps in the First World War. Not long after that he stopped practicing

medicine to concentrate on fiction.

He

was very prolific, publishing some 70 novels and over 200 short stories. From

the mid-‘20s to the ‘30s he was

remarkably successful, with a novel on the Publishers’ Weekly list of the 10

bestselling novels of the year for 7 consecutive years between 1926 and 1932.

(So that it seems that Two Black Sheep

may have been the one to break the streak!) The first of these huge bestsellers

was Sorrell and Son, third on the

list in 1926 and again fourth in 1927 (in which year his Doomsday was third). His literary reputation was never very high –

he was disparaged for his melodramatic plots, his somewhat platitudinous beliefs,

his sometimes strained views of sex and indeed of women, and, as George Orwell

wrote, as one of those writers who simply “don’t notice what is happening”.

That said, his novels were interested in significant and controversial social

issues: the Wikipedia entry lists themes such as rape, euthanasia, women posing

as men to achieve equal rights, slum conditions, pollution, and a wife

justifiably killing her husband because of abuse.

I

found a really delightful blog about Deeping, My Warwick Deeping Collection

(warwickdeeping.blogspot.com). The writer became obsessed with collecting

Deeping just a few years ago, and has copies of each of his books, and some of

the periodical versions as well. He includes a brief description of each book,

with some useful details on publication history as well, including sometimes

serial versions, and also picture of multiple editions. Just my thing! With the blog owner's permission, I've reproduced a couple of those images here, one the original Cassell edition dust jacket, and the other the cover of the Sunday Ledger reprint.

Two Black Sheep opens in about

1915 as Captain Henry Vane, on leave from the front, visits a certain Mr.

Belgrave, pulls a gun on him, and shoots him. Vane turns himself in

immediately, and is sent to prison for 15 years. It seems that Mr. Belgrave had

been fooling around with Mrs. Vane while Captain Vane was fighting in France,

and got Mrs. Vane pregnant.

Now

in 1930, Henry Vane has been released from prison. He’s an engineer, but has no

job prospects due to his record. Luckily, he’s quite well off, and he decides

to travel, figuring his case will be unknown outside of England. He ends up in

Rome. Meantime, Elsie Summerhays, a woman in her late 20s, and her mother have

been impoverished after the death of Mr. Summerhays (a writer) revealed a

mountain of debts. Elsie decides she must take a position, and is hired as a

governess by a spoiled and vulgar young widow, Mrs. Pym. Mrs. Pym and a friend

are planning to spend some months in Europe, and she needs a woman to look

after her daughter while she fools around with whatever men she fancies. So,

Elsie too ends up in Rome, in the Pym entourage, dealing with young Sally Pym,

a terribly spoiled little girl. As it happens, her room is next to Henry Vane’s,

and they meet while relaxing on neighboring balconies.

Over

the next couple of months, Elsie and Vane begin to fall in love. And Elsie,

after much difficulty, seems to be making progress in taming Sally Pym. But a

couple of disasters happen – first, Vane confesses his criminal history to

Elsie, and she reacts in shock. Before she has a chance to reconsider and to

talk again to Vane, Mrs. Pym, embarrassed both financially and romantically,

runs off to the Riviera. And Elsie learns that her mother is dying. She asks

Mrs. Pym for her salary, which that nasty woman refuses her, claiming she has

no money on hand. When Elsie finds a bunch of cash that Mrs. Pym was saving for

the casino, she takes enough for a ticket home (way less than she is owed), and

is arrested, and thrown into jail – Vane having tracked her down just a day or

so too late!

The

rest of the novel is a depiction of Vane building a home for the two in the

South of France while waiting for Elsie to serve her time – and it never

surprised from that time forward, despite a couple of manufactured crises (a