A Strange Mystery Novel: Essential Saltes, by Don Webb

A review by Rich Horton

Don Webb was born on April 30, 1960 (which makes him younger than me! Sigh). He is a prolific writer of intriguing stories, often with a horror cast. He has written three novels, ostensibly mysteries but with weird aspects, for sure, all of which I enjoyed -- but also, none in over fifteen years. But in honor of his birthday, I thought to repost this review I did of Essential Saltes, his seond novel. The first was The Double, the third Endless Honeymoon.

The dedicated SF reader does well to scrounge other then the Science Fiction shelves. Many books are hard to categorize, and many books are categorized for marketing reasons rather than any formal genre definition. (Which is fine with me, genre definitions being so hard to come by.)

Essential Saltes seems to be marketed as a mystery, and indeed it is one. It’s also arguably speculative fiction, though it’s open to multiple readings. But it’s definitely good, and filled with outrageous content that ought to satisfy our desire for the strange.

Don Webb has published boatloads of short stories. As a writer, he is weird, often funny, often strange, always interesting, and Texan. As a book, Essential Saltes is all of those things.

The protagonist is Matthew Reynman, a used-book dealer in Austin. His wife was murdered two years prior to the action, and now her ashes have been stolen. Matthew had promised to keep them and arrange for his and her ashes to be mixed and shot off in fireworks after his death. This really annoys him, and, much worse, his wife’s murderer has been released from prison in a bureaucratic snafu. Matthew tries to find the thief of his wife’s remains, and at the same time avoid being killed by his wife’s murderer.

The story involves many very odd characters, and a mix of subjects that in its eclecticness reminds me of Robertson Davies (though it’s not a very Davies-like book): fireworks, sex, race, alchemy, used books, codes and code-breaking, mental illness, polyamory, and more. There are also some tantalizing hints of a story involving Matthew’s brother John, which is the subject of Webb’s first novel, The Double, also recommended. Essential Saltes is continually interesting just for the strange characters, the odd subject matter, and the well-described sex. The plot is full of action, but at times a bit discursive, and almost too strange for me. That is, the motivations of the very strange individuals involved were perhaps a bit too odd to always hold my interest. But the rest of the book was strong enough to keep me going, and I enjoyed it quite a bit. Definitely worth reading.

Monday, April 30, 2018

Saturday, April 28, 2018

A Forgotten Ace Double: The Duplicators, by Murray Leinster/No Truce With Terra, by Philip E. High

Ace Double Reviews, 40: The Duplicators, by Murray Leinster/No Truce With Terra, by Philip E. High (#F-275, 1964, $0.40)

a review by Rich Horton

This Ace Double review is posted in memory of Philip E. High's birth, on April 28, 1914.

To be honest, this particular Ace Double really didn't excite me prior to reading. Murray Leinster (a pseudonym for Will F. Jenkins) was a respected old pro, but he's never been a particular favorite of mine. Philip E. High is an English writer who never became prominent: he's not really very good, but I find him something of a guilty pleasure. Leinster published 9 Ace Double halves in 8 separate books (plus a later reprint of the one Ace Double that featured him on both sides). High published 6 Ace Double halves. The Duplicators) is about 46,000 words long, and No Truce With Terra is about 34,000 words.

Will F. Jenkins was 68 when The Duplicators was published. He retired from writing just a few years later. His first SF story appeared way back in 1919 in the legendary all-sorts-of-fiction pulp Argosy: this was "The Runaway Skyscraper", a decent story that was reprinted in the first year of Amazing, and also a couple of times since then. He also had some mainstream success under his own name. He also had success as an inventor, holding two patents involving significant movie special effects technology. Jenkins died in 1975.

The Duplicators is an expansion of a novella called "Lord of the Uffts", from the February 1964 Worlds of Tomorrow. It takes on the idea of the matter duplicator, and like Damon Knight in A for Anything, Leinster concludes that this would be disastrous. The story begins with a rather rackety young spaceman named Link Denham getting drunk and in lots of trouble, and as a result (pretty much) signing on as astrogator on a beat up old ship owned by a disreputable and dislikable man named Thistlethwaite. Thistlethwaite is convinced he is about to make his fortune at a mysterious planet he has rediscovered.

On arrival at the planet, called Sord Three, Thistlethwaite immediately manages to be sentenced to hang, for the crime of being unmannerly. Link lasts a bit longer, but when he gives a speech to the indigenous intelligent race, the "uffts", the Household head, Harl, who has met the spaceship reluctantly decides to hang him too, despite his relatively good manners. But when Link gets to the Harl's mansion, he soon realizes that the entire economy of the planet is based on using some decaying "dupliers": duplicating machines. As a result, no human does any work, and what little work is needed is done by the uffts, in exchange for beer. But the uffts are getting restless. Worse, perhaps, the duplicating isn't working very well -- if you don't provide the right elements as raw material, the duplicated thing won't work. For example, steel knives don't duplicate very well if only iron ore is available; and electronic equipment doesn't duplicate well without, for instance, germanium for transistors. Harl has a beautiful sister, Thana, who is intelligent enough to realize the problem and try to work around it -- and Link has some ideas too. Naturally they fall in love and manage to avert his execution.

Link, perhaps a bit implausibly, quickly cottons to the disaster that dupliers have been for Sord Three, and he realizes that he must prevent the discovery of this tech by the rest of the Galaxy. He also befriends the uffts and starts to try to figure out a way to better their lot. The story, then, involves his sponsoring of an ufft revolution, his eventual solution (almost totally unbelievable) to the duplier problem, and of course his love affair with Thana. It's a breezily readable, if not plausible, novel. It's often somewhat funny. Not really very good, but not bad for half of 40 cents, I suppose.

No Truce With Terra was Philip E. High's second novel (at least according to the ISFDB), his first having been published as a single book by Ace earlier in 1964, The Prodigal Sun. Highbegan publishing short fiction in with "The Statics" in Authentic in 1955, and published quite a few short stories, mostly in UK magazines, through 1963. In 1964 he switched over almost entirely to novels, publishing some 14 through 1979. He seemed to retire at that time (he also retired from his day job, as a bus driver), but a spate of new short fiction began appearing in the Fantasy Annual series of original anthologies featuring mostly Carnell-era veterans, and other places, a total of more than thirty additional stories in the last decade of his life. He died in 2006, aged 92.

This novel begins with a scientist returning to his home only to find it impregnable -- apparently occupied by some strange being, quickly identified as an alien. These aliens seem to be metallic in nature, and to use electricity as a motivating force. They also seem all-powerful, capable of vaporizing attackers. They come in many rather terrifying forms. Soon all of England, and by extension the world, is under threat.

The scientist and a couple of friends, however, are able to analyze the aliens' means of transport, some sort of interdimensional warp gate. They copy the technology and by hit or miss open a gate to yet another planet. Their main thought is to hope at best for a lucky solution to the invader problem, or at least possibly to use this new planet as a refuge. This planet is at a low-tech developmental state, but it is also being monitored by some very advanced aliens, who soon detect the humans. These aliens make contact with the humans, and quickly offer their help. There is also a surprise about these aliens -- easily guessed in advance (I certainly did), but still I'll leave it at that.

Meanwhile, back on Earth the battle against the electronic invaders is going poorly. Even nuclear weapons are useless. But the new aliens do have some ideas ... Well, there aren't really any surprises coming.

High's prose style is fairly individual to him, and a bit shoddy. The plot here is implausible, as are the SFnal ideas ... but ... but ... The story is fast-moving and really kind of fun. The resolution is convenient but still interesting. There is one personal story that stretches belief but that I still found sweet. This is a good example of how Philip E. High could be a pleasure to read, albeit a guilty one.

a review by Rich Horton

This Ace Double review is posted in memory of Philip E. High's birth, on April 28, 1914.

To be honest, this particular Ace Double really didn't excite me prior to reading. Murray Leinster (a pseudonym for Will F. Jenkins) was a respected old pro, but he's never been a particular favorite of mine. Philip E. High is an English writer who never became prominent: he's not really very good, but I find him something of a guilty pleasure. Leinster published 9 Ace Double halves in 8 separate books (plus a later reprint of the one Ace Double that featured him on both sides). High published 6 Ace Double halves. The Duplicators) is about 46,000 words long, and No Truce With Terra is about 34,000 words.

|

| (Covers by Ed Emshwiller and Jack Gaughan) |

Will F. Jenkins was 68 when The Duplicators was published. He retired from writing just a few years later. His first SF story appeared way back in 1919 in the legendary all-sorts-of-fiction pulp Argosy: this was "The Runaway Skyscraper", a decent story that was reprinted in the first year of Amazing, and also a couple of times since then. He also had some mainstream success under his own name. He also had success as an inventor, holding two patents involving significant movie special effects technology. Jenkins died in 1975.

The Duplicators is an expansion of a novella called "Lord of the Uffts", from the February 1964 Worlds of Tomorrow. It takes on the idea of the matter duplicator, and like Damon Knight in A for Anything, Leinster concludes that this would be disastrous. The story begins with a rather rackety young spaceman named Link Denham getting drunk and in lots of trouble, and as a result (pretty much) signing on as astrogator on a beat up old ship owned by a disreputable and dislikable man named Thistlethwaite. Thistlethwaite is convinced he is about to make his fortune at a mysterious planet he has rediscovered.

On arrival at the planet, called Sord Three, Thistlethwaite immediately manages to be sentenced to hang, for the crime of being unmannerly. Link lasts a bit longer, but when he gives a speech to the indigenous intelligent race, the "uffts", the Household head, Harl, who has met the spaceship reluctantly decides to hang him too, despite his relatively good manners. But when Link gets to the Harl's mansion, he soon realizes that the entire economy of the planet is based on using some decaying "dupliers": duplicating machines. As a result, no human does any work, and what little work is needed is done by the uffts, in exchange for beer. But the uffts are getting restless. Worse, perhaps, the duplicating isn't working very well -- if you don't provide the right elements as raw material, the duplicated thing won't work. For example, steel knives don't duplicate very well if only iron ore is available; and electronic equipment doesn't duplicate well without, for instance, germanium for transistors. Harl has a beautiful sister, Thana, who is intelligent enough to realize the problem and try to work around it -- and Link has some ideas too. Naturally they fall in love and manage to avert his execution.

Link, perhaps a bit implausibly, quickly cottons to the disaster that dupliers have been for Sord Three, and he realizes that he must prevent the discovery of this tech by the rest of the Galaxy. He also befriends the uffts and starts to try to figure out a way to better their lot. The story, then, involves his sponsoring of an ufft revolution, his eventual solution (almost totally unbelievable) to the duplier problem, and of course his love affair with Thana. It's a breezily readable, if not plausible, novel. It's often somewhat funny. Not really very good, but not bad for half of 40 cents, I suppose.

No Truce With Terra was Philip E. High's second novel (at least according to the ISFDB), his first having been published as a single book by Ace earlier in 1964, The Prodigal Sun. Highbegan publishing short fiction in with "The Statics" in Authentic in 1955, and published quite a few short stories, mostly in UK magazines, through 1963. In 1964 he switched over almost entirely to novels, publishing some 14 through 1979. He seemed to retire at that time (he also retired from his day job, as a bus driver), but a spate of new short fiction began appearing in the Fantasy Annual series of original anthologies featuring mostly Carnell-era veterans, and other places, a total of more than thirty additional stories in the last decade of his life. He died in 2006, aged 92.

This novel begins with a scientist returning to his home only to find it impregnable -- apparently occupied by some strange being, quickly identified as an alien. These aliens seem to be metallic in nature, and to use electricity as a motivating force. They also seem all-powerful, capable of vaporizing attackers. They come in many rather terrifying forms. Soon all of England, and by extension the world, is under threat.

The scientist and a couple of friends, however, are able to analyze the aliens' means of transport, some sort of interdimensional warp gate. They copy the technology and by hit or miss open a gate to yet another planet. Their main thought is to hope at best for a lucky solution to the invader problem, or at least possibly to use this new planet as a refuge. This planet is at a low-tech developmental state, but it is also being monitored by some very advanced aliens, who soon detect the humans. These aliens make contact with the humans, and quickly offer their help. There is also a surprise about these aliens -- easily guessed in advance (I certainly did), but still I'll leave it at that.

Meanwhile, back on Earth the battle against the electronic invaders is going poorly. Even nuclear weapons are useless. But the new aliens do have some ideas ... Well, there aren't really any surprises coming.

High's prose style is fairly individual to him, and a bit shoddy. The plot here is implausible, as are the SFnal ideas ... but ... but ... The story is fast-moving and really kind of fun. The resolution is convenient but still interesting. There is one personal story that stretches belief but that I still found sweet. This is a good example of how Philip E. High could be a pleasure to read, albeit a guilty one.

Thursday, April 26, 2018

A Forgotten Ace Double: Siege of the Unseen, by A. E. Van Vogt/The World Swappers, by John Brunner

Ace Double Reviews, 66: Siege of the Unseen, by A. E. Van Vogt/The World Swappers, by John Brunner (#D-391, 1959, $0.35)

April 26 was A. E. Van Vogt's birthday, so here's an A. E. Van Vogt Ace Double! Siege of the Unseen is about 30,000 words long. It is apparently the same story as "The Chronicler", a two-part serial from Astounding, October and November, 1946. I'm not sure if the story was revised in any way for the 1959 reprinting. It was also reprinted once as "The Third Eye of Evil", a really pulpy title that actually is the only one of the three that has much to do with the story. As for John Brunner's The World Swappers, it is about 43,000 words, and I don't know of any earlier or different publication.

Siege of the Unseen is rather uneasily framed by a series of extracts from the coroner's report on the death of the protagonist, Michael Slade. Slade's mutilated body was found on his land -- identifiable by his third eye. I have to say I was never really worried about Slade's fate, though!

Michael Slade is a successful businessman who gets injured in a crash and suddenly develops a third eye on his forehead. He eschews treatment, and instead tries to learn to see from the third eye. As a result his wife divorces him and he is generally shunned. But when he does learn to see well with all three eyes (curing his previous two-eyed astigmatism in the process), he finds that he can transport himself to another world, apparently coexistent with Earth. This world is inhabited by three-eyed people, including a beautiful naked woman.

Before long, and somewhat against Slade's will, the woman has recruited him to come to her world and join her in a battle against the evil oppressor Geean. She dumps him in a gloomy city and says he must survive for a day. He finds that the city is inhabited by three-eyed vampires, who are apparently normal (if three-eyed) people who have been corrupted by Geean. A young woman befriends him, and tries to get him to lead an attack on Geean, but Slade doesn't feel ready -- especially when the woman asks him for a drink of blood.

Slade returns to Earth only to be recalled again, where he meets a nicer group of people, apparently primitives, but actually people living in superior harmony with nature. But they prove rather passive as to the evil Geean, and soon Slade is on his own again, before being captured by Geean forces. But Slade finds an unexpected ally, leading to his eventual confrontation with the evil leader (not to mention, of course, meeting the beautiful leading lady again ...)

It's a truly silly book, but at times the silliness is inspired. I can't say I liked it much, but I liked it more than I expected. Van Vogt could be so strange that you just had to play along at times. In John Boston's wonderful phrase, he "was the Wile E. Coyote of SF. He ran off the cliff in 1939 and looked down sometime in the 1950s."

The World Swappers is about a secret group of long-lived people plotting a better future for humanity. Which is a familiar enough idea, but Brunner uses it a bit differently than many others. It opens with a man, Saïd Counce, lying in wait for a powerful businessman. He confronts the businessman with his plan to rule the galaxy (that is, the smallish local group of planets humans have colonized). Earth, it seems, is a very nice place to live, but it is becoming overpopulated. Opening new colonies is not feasible, so the businessman plans to promote emigration to the existing colonies -- but they all resent Earthmen. Counce suggests that the businessman, Bassett, is going about things just a bit wrong, and offers his group's help, then disappears.

Then we meet others of Counce's group, on a distant unoccupied planet. They have discovered evidence of aliens, the Others, evidently humanlike but adapted to slightly different types of planets. They fear that humanity is not ready to meet the Others. Finally, we go to Ymir, the least pleasant of the human colonies, ruled by a very repressive religious sect. There we meet a rebellious young woman, Enni Zatok.

We quickly gather that Counce leads a group of people devoted to the interests of all humanity, as opposed to people like Bassett, interested only in themselves. Counce's group is desperately trying to arrange for humans to be welcoming to the aliens. In part they hope to solve the problem of Ymir -- especially as they have a plan for Ymir.

One aspect of the story I liked was the early use of matter transmission as a means of practical immortality, much as with Wil McCarthy's Queendom of Sol stories. (That is, a record of the copy of a person created when he is transmitted is saved (and possibly edited even, as with McCarthy's stories) and then the person can be recopied if his "original" dies.) That's the earliest use I can think of of this particular wrinkle on matter transmission.

On the whole, its an enjoyable novel, though a bit wobbly towards the end in particular. It tries to do too much too fast, perhaps. The noble central motivations are nicely presented, too. On the other hand, the ideas and events are often a bit strained, not quite convincing. Not Brunner at his best, at all, but as ever with him it is a decent read.

April 26 was A. E. Van Vogt's birthday, so here's an A. E. Van Vogt Ace Double! Siege of the Unseen is about 30,000 words long. It is apparently the same story as "The Chronicler", a two-part serial from Astounding, October and November, 1946. I'm not sure if the story was revised in any way for the 1959 reprinting. It was also reprinted once as "The Third Eye of Evil", a really pulpy title that actually is the only one of the three that has much to do with the story. As for John Brunner's The World Swappers, it is about 43,000 words, and I don't know of any earlier or different publication.

|

| (Covers by Ed Valigursky) |

Siege of the Unseen is rather uneasily framed by a series of extracts from the coroner's report on the death of the protagonist, Michael Slade. Slade's mutilated body was found on his land -- identifiable by his third eye. I have to say I was never really worried about Slade's fate, though!

Michael Slade is a successful businessman who gets injured in a crash and suddenly develops a third eye on his forehead. He eschews treatment, and instead tries to learn to see from the third eye. As a result his wife divorces him and he is generally shunned. But when he does learn to see well with all three eyes (curing his previous two-eyed astigmatism in the process), he finds that he can transport himself to another world, apparently coexistent with Earth. This world is inhabited by three-eyed people, including a beautiful naked woman.

Before long, and somewhat against Slade's will, the woman has recruited him to come to her world and join her in a battle against the evil oppressor Geean. She dumps him in a gloomy city and says he must survive for a day. He finds that the city is inhabited by three-eyed vampires, who are apparently normal (if three-eyed) people who have been corrupted by Geean. A young woman befriends him, and tries to get him to lead an attack on Geean, but Slade doesn't feel ready -- especially when the woman asks him for a drink of blood.

Slade returns to Earth only to be recalled again, where he meets a nicer group of people, apparently primitives, but actually people living in superior harmony with nature. But they prove rather passive as to the evil Geean, and soon Slade is on his own again, before being captured by Geean forces. But Slade finds an unexpected ally, leading to his eventual confrontation with the evil leader (not to mention, of course, meeting the beautiful leading lady again ...)

It's a truly silly book, but at times the silliness is inspired. I can't say I liked it much, but I liked it more than I expected. Van Vogt could be so strange that you just had to play along at times. In John Boston's wonderful phrase, he "was the Wile E. Coyote of SF. He ran off the cliff in 1939 and looked down sometime in the 1950s."

The World Swappers is about a secret group of long-lived people plotting a better future for humanity. Which is a familiar enough idea, but Brunner uses it a bit differently than many others. It opens with a man, Saïd Counce, lying in wait for a powerful businessman. He confronts the businessman with his plan to rule the galaxy (that is, the smallish local group of planets humans have colonized). Earth, it seems, is a very nice place to live, but it is becoming overpopulated. Opening new colonies is not feasible, so the businessman plans to promote emigration to the existing colonies -- but they all resent Earthmen. Counce suggests that the businessman, Bassett, is going about things just a bit wrong, and offers his group's help, then disappears.

Then we meet others of Counce's group, on a distant unoccupied planet. They have discovered evidence of aliens, the Others, evidently humanlike but adapted to slightly different types of planets. They fear that humanity is not ready to meet the Others. Finally, we go to Ymir, the least pleasant of the human colonies, ruled by a very repressive religious sect. There we meet a rebellious young woman, Enni Zatok.

We quickly gather that Counce leads a group of people devoted to the interests of all humanity, as opposed to people like Bassett, interested only in themselves. Counce's group is desperately trying to arrange for humans to be welcoming to the aliens. In part they hope to solve the problem of Ymir -- especially as they have a plan for Ymir.

One aspect of the story I liked was the early use of matter transmission as a means of practical immortality, much as with Wil McCarthy's Queendom of Sol stories. (That is, a record of the copy of a person created when he is transmitted is saved (and possibly edited even, as with McCarthy's stories) and then the person can be recopied if his "original" dies.) That's the earliest use I can think of of this particular wrinkle on matter transmission.

On the whole, its an enjoyable novel, though a bit wobbly towards the end in particular. It tries to do too much too fast, perhaps. The noble central motivations are nicely presented, too. On the other hand, the ideas and events are often a bit strained, not quite convincing. Not Brunner at his best, at all, but as ever with him it is a decent read.

Wednesday, April 25, 2018

The Hugo Ballot: Novella

Novella

The nominees are:

All Systems Red,

by Martha Wells (Tor.com Publishing)

"And Then There Were (N-One)," by Sarah Pinsker (Uncanny, March/April 2017)

Binti: Home, by

Nnedi Okorafor (Tor.com Publishing)

The Black Tides of

Heaven, by JY Yang (Tor.com Publishing)

Down Among the Sticks

and Bones, by Seanan McGuire (Tor.Com Publishing)

River of Teeth,

by Sarah Gailey (Tor.com Publishing)

My views here are fairly simple. It’s a decent shortlist,

but a bifurcated one. There are three nominees that are neck and neck in my

view, all first-rate stories and well worth a Hugo. And there are three that

are OK, but not special – in my view not Hugo-worthy (but not so obviously

unworthy that I will vote them below No Award.)

My ballot will look like this:

1.

Sarah Pinsker, “And Then There Were (N – One)” –

A story about a convention of alternate Sarah Pinskers, complete with a murder.

It is warmly told – funny at time, certainly the milieu is familiar to any SF

con-goer. But it’s dark as well – after, there’s a murder – and it

intelligently deals with issue of identity and contingency.

2.

Martha Wells, All Systems Red – a

ripping good novella about a security android which calls itself a murderbot,

guarding a group of researchers on an alien planet. The murderbot mainly wants

peace to watch its favorite TV shows, but that becomes impossible when the team

comes under threat. It soon becomes clear that there is an unexpected group on

the planet that doesn’t want any rivals, and the murderbot has to work with its

humans to find a way to safety. That part – the plotty part – is nicely done,

but the depiction of the murderbot is the story’s heart: convincingly a real

person but not a human, with emotions but not those that humans expect: very

funny at times but also quite moving.

3.

Seanan McGuire, Down Among the Sticks and Bones – I was rather disappointed by

Every Heart a Doorway, the first novella in McGuire’s Wayward Children series.

I thought its main character boring, and its murder mystery plot rather a mess,

and I thought the story just too long. For that reason, I passed on Down Among

the Sticks and Bones until it showed up on the Hugo shortlist. So I came to the

story with low expectations – and I was completely delighted. This isn’t just

better than Every Heart a Doorway – it’s LOTS better. This tells the backstory

of Jack and Jill, very important characters from the first book. They are

twins, born to a couple who aren’t really interested in children except for how

they look to their colleagues, and who force them into their ideas of the perfect

girls – Jacqueline is the pretty one (thought they look the same), intended to

be the popular one; while Jillian is the tomboy, the soccer player, the

adventurer. (The one weakness of the story is the characterization of the

parents – they’re a cliché, their faults seem forced.) The things is, that’s

not who the girls really are, and when they find a door into another world,

they take it, ending up on the Moors, a very dangerous place, ruled by a

vampire, and featuring other horrors like werewolves. Jack stays with a

relatively good man, and exercises her interest in learning and scientific

research. Jill stays with the vampire, wanting to become a vampire herself –

his heir, indeed. But when Jack takes a local girl as her lover, Jill’s

eventual reaction catalyzes the inevitable ending.

4.

Sarah Gailey, River of Teeth – a caper story (OK, not a caper – an operation!)

about a mixed team of “hoppers” (hippopotamus wranglers, basically) assembled

to clear the lower Mississippi of feral hippos. Their leader, Winslow Houndstooth,

also wants revenge, against the man who burned down his hippo farm years

before. There’s a lot of violence, a truly evil villain, and a fair amount of

believable darkness. I mean, I enjoyed it. I just didn’t see it as special – in

particular in a speculative sense – yes, there’s the fairly cool alternate

history aspect involving the hippos in Louisiana, but nothing with real SFnal

zing. Still – it’s pretty fun.

5.

JY Yang, The

Black Tides of Heaven – The story concerns the twin children of the

Protector, originally promised to the local Monastery. But one of them turns

out to have precognitive powers, and the Protector claims them … the other

strikes off on their own, ending up in a rebellion against their mother. The

good – a decent magic system (alas, treated in a clichéd fashion on occasion),

interesting if seemingly inconsistent and underdeveloped treatment of gender (to

be fair, the supposed inconsistencies may well be eventually explained), and

decent characters. The not-so-good: a fairly clichéd plot (which doesn’t really

resolve, though to be sure its companion novella was released in parallel, and

that may illuminate the story), rather ordinary prose, and some pacing issues,

mainly in the opening section (about a fourth of the story), which really

should have been almost entirely cut. Bottom line – an okay story that has been

ridiculously overpraised.

6.

Nnedi Okorafor, Binti: Home – Much as with Every Heart a Doorway, I was puzzled by

the extravagant praise Binti received – I thought it kind of a mess, really

illogical, hard to believe. Alas, the sequel, unlike the McGuire story’s

prequel, is not much better than the opening, in my view. (Also, it doesn’t

come to a real conclusion.) Binti, after spending some time at Oomza Uni, comes

home to her family for a visit, and a pilgrimage. She is accompanied by her

friend Okwu, one of the murderous Meduse (who also altered Binti’s genetics,

though they didn’t kill her, unlike all her innocent prospective classmates). The

notion is apparently to make some repairs in the Meduse’s relationship with humans,

especially the Koush, a rival people to Binti’s Himba. But little enough happens

on that ground (presumably that’s left for the next installment) – instead,

Binti’s pilgrimage becomes a trip to the home of the mysterious Desert People,

who turn out to be part of her ancestry, and to have a relationship going far

back in history with a group of aliens with special tech. I have to say, my

main problem was that I just didn’t believe in the story, nor, really, in

Binti. It’s obvious a lot of people love these stories, and so it’s clear they’re

seeing something I’m missing. So be it – the fault may well lie with me. But I

didn’t like this story much, to be honest.

My nominees were, in alphabetical order by author:

1.

Kathleen Ann Goonan, “The Tale of the Alcubierre

Horse”

2.

Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Prime Meridian

3.

Sofia Samatar, “Fallow”

4.

Sarah Pinsker, “And Then There Were (N – One)”

5.

Martha Wells, All Systems Red

In reality, the three that weren’t nominated are easy to

understand – they are the three least readily available. Goonan’s story is from

an original anthology (and one that didn’t seem to get a ton of attention, Extrasolar, from PS Publishing in the

UK). Samatar’s story is from her exceptional collection Tender, and story collections typically get less attention, especially for original stories, than either magazines or anthologies. Moreno-Garcia’s may be the most obscure – available only to

supports of her Indiegogo campaign (and to lucky reviewers!) Indeed, I suspect

it might be eligible for next year’s Hugo. But there were plenty of other

worthy potential nominees; for instance Damien Broderick’s “Tao Zero”, Dave Hutchinson’s

Acadie, and Jeremiah Tolbert’s “The

Dragon of Dread Peak”.

Monday, April 23, 2018

The Hugo Ballot: Novelette

Novelette

The nominees are:

“Children of

Thorns, Children of Water,” by Aliette de Bodard (Uncanny, July-August 2017)

“Extracurricular Activities,” by Yoon Ha Lee (Tor.com,

February 15, 2017)

“The Secret Life of Bots,” by Suzanne Palmer (Clarkesworld, September 2017)

“A Series of Steaks,” by Vina Jie-Min Prasad (Clarkesworld, January 2017)

“Small Changes Over Long Periods of Time,” by K.M. Szpara (Uncanny, May/June 2017)

“Wind Will Rove,” by Sarah Pinsker (Asimov’s, September/October 2017)

This is really a very strong shortlist. The strongest

shortlist in years and years, I’d say. Two are stories I nominated, and two

more were on my personal shortlist of stories I considered nominating. The

other two stories are solid work, though without quite the little bit extra I

want in an award winner.

My ballot will look like this. I’ll mention that first two

were 1 and 2 on my list before the shortlist was announced, which is pretty

unusual!

1. Yoon Ha Lee, “Extracurricular Activities”

(Tor.com, 2/17) – a quite funny, and quite clever, story concerning the earlier

life of a very significant character in Lee’s two novels, both Hugo nominees

themselves, Ninefox Gambit and Raven Stratagem. Shuos Jedao is an undercover operative for the Heptarchate, assigned to

infiltrate a space station controlled by another polity, and to rescue the crew

of a merchanter ship that had really been heptarchate spies, including an old

classmate.

2.

Suzanne Palmer, “The Secret Life of Bots” (Clarkesworld, 9/17) – a very old bot on a battered Ship trying to

stop an alien attack on Earth. It shows a surprising amount of initiative –

even, one might say, imagination – in dealing with the Incidental. Might that

not be useful in dealing with the aliens? Or might bots have their own ideas

about their own place? Very strong work indeed.

3.

Sarah Pinsker, “Wind Will Rove” (Asimov’s, 9-10/17) – a story about the folk process, and memory,

and the occasional importance of forgetting, set on a generation ship. Rosie is

a middle-aged teacher on the ship, and a pretty good fiddle player. A malicious

virus wiped most of the ship’s memory not too long into the journey, and Rosie

and her fellows work on restoring what’s been lost by remembering everything

they can, including folk tunes. But some of her students resent being taught

history – another form of remembering – why should they re-create Earth on the

ship, or even the new planet (that they will never see)? Even Rosie’s daughter

has doubts. But purposeful forgetting – or malicious erasing – hardly seems

right either. These questions are considered in the light of Rosie thinking

about a particular folk tune, “Windy Grove”, a favorite of her grandmother’s,

and how it changed over time – and might still change. Thoughtful and quite

moving.

4.

Vina Jie-Min Prasad, “A Series of Steaks” (Clarkesworld, 1/17) -- Helena is a frustrated art student who, in

order to make ends meet, has turned to forging steak using a 3-D printer (in

this future, real meat is very rare (pun intended!).). She’s pretty good at it

actually (it’s an art!), but then she receives a huge order for a bunch of

T-bones … with a blackmail threat attached. The story turns into a bit of a

caper story, with a bit of a love story attached – effectively enough. The

original central idea, and nice characters, lifted it above the ordinary for

me.

5.

Aliette de Bodard, “Children of Thorns, Children

of Water” (Uncanny, 7-8/17) – set in a fantastical Paris ruled by houses

of Angels, a couple of adversaries are trying to infiltrate House Hawthorn (using

among other things cooking skills). It’s a story I liked – and a story that

made me want to read the other works in this milieu – but it didn’t quite seem

finished to me, more an outtake or pendant to its overall series.

6.

K. M. Szpara, “Small Changes Over Long Periods

of Time” (Uncanny, 5-6/17) – Not a bad story at all, but not one that

thrilled me. It’s a vampire story, and a gay/transgender story. The first

aspect is, if I’m honest, a bit of a negative for me, which isn’t fair, I

guess, but it’s real – I’ve been tired of vampires for a long time. The second

aspect is just fine, and nicely – but maybe just a bit obviously – integrated with

the vampire theme. Nothing wrong with any of this, but for me it all added up

to “fine work, but not really award-worthy”. Many others’ mileage varied, which

is fine.

Obviously several novelettes I nominated didn’t make the

cut, but while I’ll still say that if “Soulmates.com” or “The Hermit of Houston”

or “ZeroS” or “Keepsakes” or a couple others had made that ballot it would be

marginally better, I really can’t complain about the ballot we got.

A Significant Ace Double: Rocannon's World, by Ursula K. Le Guin/The Kar-Chee Reign, by Avram Davidson

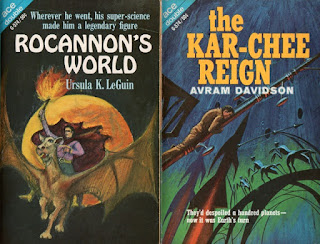

Ace Double Reviews, 10: Rocannon's World, by Ursula K. Le Guin/The Kar-Chee Reign, by Avram Davidson (#G-574, 1966, $0.50)

(This April 23 repost is in honor of Avram Davidson's birthday, 23 April 1923.)

Ace Doubles have a fairly declassé image. One doesn't tend to look for all time classics or Hugo candidates among them. Though as previous reviews in this series have shown, there were first rate novels and novellas published as Ace Double halves, such as Jack Vance's Hugo winner "The Dragon Masters". (That was, however, a reprint.) But even so, it's something of a surprise to see that Ursula Le Guin's first novel was first published as half of an Ace Double. Rocannon's World is about 44,000 words long. It was expanded from a 7700 word story, "Dowry of the Angyar", which was in the September 1964 Amazing. This story appears unchanged as the prologue to Rocannon's World (called here "The Necklace"), and it has latterly been reprinted by itself under Le Guin's preferred title, "Semley's Necklace".

If Ursula Le Guin is a mild surprise as an Ace Double author (her second novel, Planet of Exile, was also an Ace Double half), so too might be Avram Davidson. Though it should be noted that Davidson's early novels were fairly routine, rather pulpish, not terribly characteristic of his best work. The Kar-Chee Reign is a 49,000 word novel, a prequel to his 1965 Ace novel (not an Ace Double half!) Rogue Dragon. Rogue Dragon itself was nominated for a Nebula Award, but The Kar-Chee Reign, a lesser work, to my mind, was not. The two novels were reprinted together in 1979, in a volume bannered "Ace Double", but not a true Ace Double. That is, it was not published in dos-a-dos format, and not part of a regular series. Rather, Ace essentially put out a few single author "omnibus" editions of two novels at about that time, and called them Ace Doubles in a nod to their past.

Ursula K. Le Guin, one of the greatest SF/Fantasy writers of all time (arguably the greatest), indeed one of the greatest American writers of her generation, died January 22, 2018, aged 88. Le Guin was a favorite of mine since I first encountered her work in the early 1970s. She was best known for her SF novels The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness, and for her fantasy trilogy for young adults, The Earthsea Trilogy (later extended with two more books). I loved those books, but also her first written novel, Malafrena, and her last novel, Lavinia, and most everything she published in between, including any number of remarkable short stories. (My favorite is "The Stars Below".)

Her first published novel, Rocannon's World is a perhaps a bit curious, but clearly on the road to her mature work. It is a "Hainish" novel, thus fitting into Le Guin's main "future history", but it doesn't seem wholly consistent with novels like The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed. (And indeed Le Guin acknowledged that inconsistency, and wasn't much bothered by it.) What it mainly is is a fantasy novel with SF trappings. Except for the prose, which is excellent as one might expect from Le Guin, it feels strikingly pulpish. (The plot and feel would not have been out of place in an early 50s issue of Planet Stories, and in fact much of the content of Planet Stories was fantasy with SF trappings, work that might have been published as pure fantasy once the market for that exploded after the paperback publication of The Lord of the Rings.) Perhaps the influence of Leigh Brackett or Andre Norton can be detected. The ultimate effect is mixed -- the plot is just not terribly plausible in places, and some of the setting and trappings are a bit old hat. But as I said the prose is fine, and the romantic and melancholy overtones are extremely effective.

Fomalhaut II is a planet which has only been lightly explored by the League of All Words (in later novels, the Ekumen). The League does not even know how many intelligent races live there -- three for sure, but perhaps two more. One non-humanoid race is not even encountered in the book. The main races are the Liuar (basically "humans"); and the now split Gdemiar (Clayfolk -- dwarf-analogues) and Fiia (elf-analogues). The League has been promoting the advancement of the Gdemiar to an industrial society, and extracting taxes from them and the Liuar, but after the ethnologist Rocannon encounters Semley (an aristocrat of the Liuar) in the prologue, he decides the world is not well enough understood, and he mounts an expedition to study it. But disaster strikes -- an enemy race is there as well, and they find and destroy Rocannon's spaceship, marooning him with none of his equipment.

He then must travel, with the help of Semley's grandson and a small band of locals, to the mysterious Southwest continent where the enemy is located, hoping to find an ansible and call for help. Their journey, mostly on rather unlikely flying "horses", or windsteeds, is full of adventure -- they encounter various different sorts of outlaws, and danger from the weather, and a scary quasi-intelligent race, and finally an unconvincing "Old One" who grants Rocannon special powers, helping him finally accomplish his mission. All this is entertaining but as I have said faintly pulpish and not very plausible. But the final resolution is achingly bittersweet, deeply romantic and very melancholy. Certainly a novel worth reading, though of course Le Guin has done much better things.

Avram Davidson (1923-1993) was also one of the SF field's best, and most original, writers. He wrote a number of exceptional short stories (my favorite among them is one of the greatest SF stories of all time, "The Sources of the Nile"), and quite a few novels. The novels, especially the later novels, were interesting but not as brilliant as the short stories. He sometimes seemed to lose interest the more he wrote about something, and indeed he started several series that he never finished. He was also editor of F&SF between 1962 and 1964. Two series of stories are particularly worth notice: the Eszterhazy stories, and the Limekiller stories, and his nonfiction about the sources of certain legends, Adventures in Unhistory, is quite absorbing.

I haven't read The Kar-Chee Reign in some little time, so the following summary may be a bit lacking. It is set far in the future. Humans have colonized other stars, and have forgotten Earth. Earth itself is, as Davidson puts it "flat, empty, weary and bare". A few humans remain, apparently living a low-tech style of life. Then the insectlike aliens the Kar-Chee come, to mine the Earth for its remaining metals, with the help of huge beasts called Dragons by the humans. The Kar-Chee hardly care about humans, displacing them without much thought or worry. Humans have come to cower away from the Kar-Chee, avoiding them in hopes of escaping notice.

The Rowan family lives in fair comfort on an isolated island that the Kar-Chee have not yet reached. When the aliens finally do come, certain of the locals seem to have forgotten the policy of avoiding them at all costs, and a series of attacks are mounted. These attacks meet with initial success, but then the Kar-Chee are irritated, and reprisals occur. But a group led by one Liam decides to continue to take the fight to the Kar-Chee. It will not be a great surprise that they are eventually successful, and Liam becomes a celebrated hero. The Kar-Chee depart, but they leave some of the Dragons behind (setting up Rogue Dragon, set some time further in the future). There is also an indication that contact with the human-colonized worlds will resume, and that Earth itself will be revitalized.

It's far from a great novel, and it's far from Davidson at anything like his best. Still, I do recall enjoying it, though I thought the action in general routine (and sometimes confused), and much of the setup a bit silly. The prose shows only hints of pure Davidson.

(This April 23 repost is in honor of Avram Davidson's birthday, 23 April 1923.)

Ace Doubles have a fairly declassé image. One doesn't tend to look for all time classics or Hugo candidates among them. Though as previous reviews in this series have shown, there were first rate novels and novellas published as Ace Double halves, such as Jack Vance's Hugo winner "The Dragon Masters". (That was, however, a reprint.) But even so, it's something of a surprise to see that Ursula Le Guin's first novel was first published as half of an Ace Double. Rocannon's World is about 44,000 words long. It was expanded from a 7700 word story, "Dowry of the Angyar", which was in the September 1964 Amazing. This story appears unchanged as the prologue to Rocannon's World (called here "The Necklace"), and it has latterly been reprinted by itself under Le Guin's preferred title, "Semley's Necklace".

|

| (Covers by Gerald McConnell and Jack Gaughan) |

If Ursula Le Guin is a mild surprise as an Ace Double author (her second novel, Planet of Exile, was also an Ace Double half), so too might be Avram Davidson. Though it should be noted that Davidson's early novels were fairly routine, rather pulpish, not terribly characteristic of his best work. The Kar-Chee Reign is a 49,000 word novel, a prequel to his 1965 Ace novel (not an Ace Double half!) Rogue Dragon. Rogue Dragon itself was nominated for a Nebula Award, but The Kar-Chee Reign, a lesser work, to my mind, was not. The two novels were reprinted together in 1979, in a volume bannered "Ace Double", but not a true Ace Double. That is, it was not published in dos-a-dos format, and not part of a regular series. Rather, Ace essentially put out a few single author "omnibus" editions of two novels at about that time, and called them Ace Doubles in a nod to their past.

Ursula K. Le Guin, one of the greatest SF/Fantasy writers of all time (arguably the greatest), indeed one of the greatest American writers of her generation, died January 22, 2018, aged 88. Le Guin was a favorite of mine since I first encountered her work in the early 1970s. She was best known for her SF novels The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness, and for her fantasy trilogy for young adults, The Earthsea Trilogy (later extended with two more books). I loved those books, but also her first written novel, Malafrena, and her last novel, Lavinia, and most everything she published in between, including any number of remarkable short stories. (My favorite is "The Stars Below".)

Her first published novel, Rocannon's World is a perhaps a bit curious, but clearly on the road to her mature work. It is a "Hainish" novel, thus fitting into Le Guin's main "future history", but it doesn't seem wholly consistent with novels like The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed. (And indeed Le Guin acknowledged that inconsistency, and wasn't much bothered by it.) What it mainly is is a fantasy novel with SF trappings. Except for the prose, which is excellent as one might expect from Le Guin, it feels strikingly pulpish. (The plot and feel would not have been out of place in an early 50s issue of Planet Stories, and in fact much of the content of Planet Stories was fantasy with SF trappings, work that might have been published as pure fantasy once the market for that exploded after the paperback publication of The Lord of the Rings.) Perhaps the influence of Leigh Brackett or Andre Norton can be detected. The ultimate effect is mixed -- the plot is just not terribly plausible in places, and some of the setting and trappings are a bit old hat. But as I said the prose is fine, and the romantic and melancholy overtones are extremely effective.

Fomalhaut II is a planet which has only been lightly explored by the League of All Words (in later novels, the Ekumen). The League does not even know how many intelligent races live there -- three for sure, but perhaps two more. One non-humanoid race is not even encountered in the book. The main races are the Liuar (basically "humans"); and the now split Gdemiar (Clayfolk -- dwarf-analogues) and Fiia (elf-analogues). The League has been promoting the advancement of the Gdemiar to an industrial society, and extracting taxes from them and the Liuar, but after the ethnologist Rocannon encounters Semley (an aristocrat of the Liuar) in the prologue, he decides the world is not well enough understood, and he mounts an expedition to study it. But disaster strikes -- an enemy race is there as well, and they find and destroy Rocannon's spaceship, marooning him with none of his equipment.

He then must travel, with the help of Semley's grandson and a small band of locals, to the mysterious Southwest continent where the enemy is located, hoping to find an ansible and call for help. Their journey, mostly on rather unlikely flying "horses", or windsteeds, is full of adventure -- they encounter various different sorts of outlaws, and danger from the weather, and a scary quasi-intelligent race, and finally an unconvincing "Old One" who grants Rocannon special powers, helping him finally accomplish his mission. All this is entertaining but as I have said faintly pulpish and not very plausible. But the final resolution is achingly bittersweet, deeply romantic and very melancholy. Certainly a novel worth reading, though of course Le Guin has done much better things.

Avram Davidson (1923-1993) was also one of the SF field's best, and most original, writers. He wrote a number of exceptional short stories (my favorite among them is one of the greatest SF stories of all time, "The Sources of the Nile"), and quite a few novels. The novels, especially the later novels, were interesting but not as brilliant as the short stories. He sometimes seemed to lose interest the more he wrote about something, and indeed he started several series that he never finished. He was also editor of F&SF between 1962 and 1964. Two series of stories are particularly worth notice: the Eszterhazy stories, and the Limekiller stories, and his nonfiction about the sources of certain legends, Adventures in Unhistory, is quite absorbing.

I haven't read The Kar-Chee Reign in some little time, so the following summary may be a bit lacking. It is set far in the future. Humans have colonized other stars, and have forgotten Earth. Earth itself is, as Davidson puts it "flat, empty, weary and bare". A few humans remain, apparently living a low-tech style of life. Then the insectlike aliens the Kar-Chee come, to mine the Earth for its remaining metals, with the help of huge beasts called Dragons by the humans. The Kar-Chee hardly care about humans, displacing them without much thought or worry. Humans have come to cower away from the Kar-Chee, avoiding them in hopes of escaping notice.

The Rowan family lives in fair comfort on an isolated island that the Kar-Chee have not yet reached. When the aliens finally do come, certain of the locals seem to have forgotten the policy of avoiding them at all costs, and a series of attacks are mounted. These attacks meet with initial success, but then the Kar-Chee are irritated, and reprisals occur. But a group led by one Liam decides to continue to take the fight to the Kar-Chee. It will not be a great surprise that they are eventually successful, and Liam becomes a celebrated hero. The Kar-Chee depart, but they leave some of the Dragons behind (setting up Rogue Dragon, set some time further in the future). There is also an indication that contact with the human-colonized worlds will resume, and that Earth itself will be revitalized.

It's far from a great novel, and it's far from Davidson at anything like his best. Still, I do recall enjoying it, though I thought the action in general routine (and sometimes confused), and much of the setup a bit silly. The prose shows only hints of pure Davidson.

Saturday, April 21, 2018

The Hugo Ballot, Short Story

Here's the first of what will be a series of posts detailing my thoughts on my final ballot ordering for a number of the Hugo categories.

Short Story

The Hugo shortlist is:

"Carnival Nine" by Caroline M. Yoachim (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, May 2017)

"Clearly Lettered in a Mostly Steady Hand", by Fran Wilde (Uncanny, September 2017)

"Fandom for Robots", by Vina Jie-Min Prasad (Uncanny, September/October 2017)

"The Martian Obelisk," by Linda Nagata (Tor.com, July 19, 2017)

"Sun, Moon, Dust", by Ursula Vernon (Uncanny, May/June 2017)

"Welcome to your Authentic Indian Experience[TM]", by Rebecca Roanhorse (Apex, August 2017)

This is by no means a bad shortlist. Every story on it is at least pretty decent. My ballot will look like this:

1. “The Martian Obelisk”, by Linda Nagata – This is set in a future in which a series of disasters, with causes in human nature, in environmental collapse, and in technological missteps, has led to a realization that humanity is doomed. One old architect, in a gesture of, perhaps, memorialization of the species, has taken over the remaining machines of an abortive Mars colony to create a huge obelisk that might end up the last surviving great human structure after we are gone. But her project is threatened when a vehicle from one of the other Martian colonies (all of which failed) approaches. Is the vehicle’s AI haywire? Has it been hijacked by someone else on Earth? The real answer is more inspiring – and if perhaps just a bit pat, the conclusion is profoundly moving.

2. “Fandom for Robots”, by Vina Jie-Min Prasad – a quite delightful story of a 1950s robot (called Computron, natch!) writing fan fiction about an anime called Hyperdimension Warp Record. Prasad pulls it off with a perfect deadpan delivery, which makes Computron, as it were, come alive – and which captures the fan fiction culture right on the nose.

3. “Clearly Lettered in a Mostly Steady Hand”, by Fran Wilde – a story of a visit to a museum exhibition that in the end seems to be a “freak show”, and which has a distinct and scary effect on the visitor. It’s told in the second person, and this is (perhaps rarely!) the exactly correct choice for this story, as the reader slowly realizes that the act of viewing the perhaps grotesque (or just misunderstood?) exhibits has parallels with how they see people who are different. I will say that this is a story that improved on rereading – either because my mood was different, or because I saw more on a second pass.

4. “Carnival Nine”, by Caroline M. Yoachim – a nice take on the notion of windup dolls that are truly alive, as Zee, blessed with a mainspring that takes extra winding, grows up with her beloved Papa, marries a nice young boy, and then makes a child who can hardly be wound at all. It’s a simple idea, and told straightforwardly, with no compromises or miracles.

5. “Sun, Moon, Dust”, by Ursula Vernon – a fine magic sword story in which Allpa’s grandmother leaves him a sword on her death, with the three title warriors enchanted into it to teach him to fight. But Allpa is a farmer, and doesn’t see much need for a sword, much to the frustration of Sun, Moon, and Dust. Allpa has plenty to learn, but maybe he has more to teach – and maybe perhaps one of these warriors will realize that there’s more to life than war.

6. "Welcome to your Authentic Indian ExperienceTM", by Rebecca Roanhorse – another second person story, and while that’s done well enough, it doesn’t seem quite as effective a choice as in the Wilde story. It’s the story of a Native American man working in a near future tourist destination where people can have “authentic” virtual experience of historical Indian life – but instead of being truly “authentic” the experiences are overlaid with typical fake Indian clichés. I thought it was fine, well worth reading, but it didn’t really wow me.

On reflection and rereading, even though I only nominated one of these stories (and the second wasn’t too far off my nomination ballot), I’m pretty happy with the nominations of the top four stories on my ballot, and the other two are solid work that I can’t and don’t complain about. That said, the nominators missed some outstanding work, I think largely on the basis of ready availability.

My prime nomination candidates were:

Maureen McHugh, "Sidewalks" (Omni, Winter/17)

Giovanni de Feo, "Ugo" (Lightspeed, 9/17)

Charlie Jane Anders, "Don’t Press Charges and I Won’t Sue" (Boston Review, Global Dystopias)

Sofia Samatar, “An Account of the Land of Witches” (Tender)

Linda Nagata, "The Martian Obelisk" (Tor.com, 7/17)

Karen Joy Fowler, "Persephone of the Crows" (Asimov’s, 5-6/17)

Tobias Buckell, "Zen and the Art of Starship Maintenance" (Cosmic Powers)

The only one of those stories (besides the Nagata, which made the ballot) that was as readily available as the six stories on the final ballot is de Feo’s “Ugo”, a first story by an Italian writer. The other stories are all outstanding. I would say that the Anders, McHugh, and Samatar stories are particularly big misses, and in each case the story appeared in a print publication that was very easy for a reader to miss. Them’s the berries, I guess. For all that, I have to say that this is one of the best Short Story Hugo ballots in a long time.

I’ll note that all six nominees are women – and that that seems fair, this year. Yes, Tobias Buckell and Giovanni de Feo did work on a level with all these women (Anders, Samatar, Fowler, and McHugh included), but they didn’t do work obviously better.

Short Story

The Hugo shortlist is:

"Carnival Nine" by Caroline M. Yoachim (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, May 2017)

"Clearly Lettered in a Mostly Steady Hand", by Fran Wilde (Uncanny, September 2017)

"Fandom for Robots", by Vina Jie-Min Prasad (Uncanny, September/October 2017)

"The Martian Obelisk," by Linda Nagata (Tor.com, July 19, 2017)

"Sun, Moon, Dust", by Ursula Vernon (Uncanny, May/June 2017)

"Welcome to your Authentic Indian Experience[TM]", by Rebecca Roanhorse (Apex, August 2017)

This is by no means a bad shortlist. Every story on it is at least pretty decent. My ballot will look like this:

1. “The Martian Obelisk”, by Linda Nagata – This is set in a future in which a series of disasters, with causes in human nature, in environmental collapse, and in technological missteps, has led to a realization that humanity is doomed. One old architect, in a gesture of, perhaps, memorialization of the species, has taken over the remaining machines of an abortive Mars colony to create a huge obelisk that might end up the last surviving great human structure after we are gone. But her project is threatened when a vehicle from one of the other Martian colonies (all of which failed) approaches. Is the vehicle’s AI haywire? Has it been hijacked by someone else on Earth? The real answer is more inspiring – and if perhaps just a bit pat, the conclusion is profoundly moving.

2. “Fandom for Robots”, by Vina Jie-Min Prasad – a quite delightful story of a 1950s robot (called Computron, natch!) writing fan fiction about an anime called Hyperdimension Warp Record. Prasad pulls it off with a perfect deadpan delivery, which makes Computron, as it were, come alive – and which captures the fan fiction culture right on the nose.

3. “Clearly Lettered in a Mostly Steady Hand”, by Fran Wilde – a story of a visit to a museum exhibition that in the end seems to be a “freak show”, and which has a distinct and scary effect on the visitor. It’s told in the second person, and this is (perhaps rarely!) the exactly correct choice for this story, as the reader slowly realizes that the act of viewing the perhaps grotesque (or just misunderstood?) exhibits has parallels with how they see people who are different. I will say that this is a story that improved on rereading – either because my mood was different, or because I saw more on a second pass.

4. “Carnival Nine”, by Caroline M. Yoachim – a nice take on the notion of windup dolls that are truly alive, as Zee, blessed with a mainspring that takes extra winding, grows up with her beloved Papa, marries a nice young boy, and then makes a child who can hardly be wound at all. It’s a simple idea, and told straightforwardly, with no compromises or miracles.

5. “Sun, Moon, Dust”, by Ursula Vernon – a fine magic sword story in which Allpa’s grandmother leaves him a sword on her death, with the three title warriors enchanted into it to teach him to fight. But Allpa is a farmer, and doesn’t see much need for a sword, much to the frustration of Sun, Moon, and Dust. Allpa has plenty to learn, but maybe he has more to teach – and maybe perhaps one of these warriors will realize that there’s more to life than war.

6. "Welcome to your Authentic Indian ExperienceTM", by Rebecca Roanhorse – another second person story, and while that’s done well enough, it doesn’t seem quite as effective a choice as in the Wilde story. It’s the story of a Native American man working in a near future tourist destination where people can have “authentic” virtual experience of historical Indian life – but instead of being truly “authentic” the experiences are overlaid with typical fake Indian clichés. I thought it was fine, well worth reading, but it didn’t really wow me.

On reflection and rereading, even though I only nominated one of these stories (and the second wasn’t too far off my nomination ballot), I’m pretty happy with the nominations of the top four stories on my ballot, and the other two are solid work that I can’t and don’t complain about. That said, the nominators missed some outstanding work, I think largely on the basis of ready availability.

My prime nomination candidates were:

Maureen McHugh, "Sidewalks" (Omni, Winter/17)

Giovanni de Feo, "Ugo" (Lightspeed, 9/17)

Charlie Jane Anders, "Don’t Press Charges and I Won’t Sue" (Boston Review, Global Dystopias)

Sofia Samatar, “An Account of the Land of Witches” (Tender)

Linda Nagata, "The Martian Obelisk" (Tor.com, 7/17)

Karen Joy Fowler, "Persephone of the Crows" (Asimov’s, 5-6/17)

Tobias Buckell, "Zen and the Art of Starship Maintenance" (Cosmic Powers)

The only one of those stories (besides the Nagata, which made the ballot) that was as readily available as the six stories on the final ballot is de Feo’s “Ugo”, a first story by an Italian writer. The other stories are all outstanding. I would say that the Anders, McHugh, and Samatar stories are particularly big misses, and in each case the story appeared in a print publication that was very easy for a reader to miss. Them’s the berries, I guess. For all that, I have to say that this is one of the best Short Story Hugo ballots in a long time.

I’ll note that all six nominees are women – and that that seems fair, this year. Yes, Tobias Buckell and Giovanni de Feo did work on a level with all these women (Anders, Samatar, Fowler, and McHugh included), but they didn’t do work obviously better.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)