Gordon R. Dickson was born November 1st, 1923, so his 97th birthday was a few days ago. I realized I hadn't ever done one of these short fiction review assemblages for him before (I did review his Ace Double The Genetic General/Time to Teleport), and so I put together a collection of all the short fiction I'd happened to write about when discussing old SF magazines. Then I remembered that the cover story of the very first SF magazine I ever bought, the August 1974 Analog, was by Dickson, and I figured I should write about that too! But that required some excavation in my boxes of old Analogs, and thus this birthday review is a bit late!

Astounding, February 1952

"Steel Brother" may have been the first solo Gordon Dickson story to make a lasting impact. It's about a Solar System Frontier Guard, Thomas Jordan. The Frontier Guards man a somewhat implausible series of station at the edge of the Solar System, which each control a phalanx of robot ships that attack the aliens that periodically try to invade. Thomas Jordan has just taken his first command, and he's convinced he's a coward. He's also afraid of the implanted connection to the stored memories of all his predecessors (the "steel brother"): he's heard stories of people losing their identity and being overwhelmed by the memories. So when his first attack comes, he funks it, and almost lets the alien ships through, until he finally allows the "steel brother" to help -- and learns a lesson about, well, comradeship. There's a typically Dicksonian ambition, and a sort of ponderousness, to the story -- which nonetheless didn't really work for me, it seemed strained.

Universe, December 1953

The other novelette is also light comedy: "The Adventure of the Misplaced Hound" (9200 words), one of Poul Anderson and Gordon R. Dickson's Hoka stories. I've never been as big a fan of the Hoka stories as many readers, though I think to some extent I burden the entire series with my dislike of the one late novel, Star Prince Charlie, which I think was quite poor. This story is decent enough, though not really great. The Hokas, of course, are teddy bear like aliens who love to imitate fictional models -- in this story, obviously, they are imitating Sherlock Holmes. Much to the distress of a human IBI agent who is tracking down a nasty alien drug runner who has chosen to hide near the Hoka equivalent of the Baskerville mansion.

Galaxy, January 1954

The novelets are Gordon R. Dickson's "Lulungomeena" (6500 words), and Winston Marks's "Backlash" (8800 words). "Lulungomeena" is a story that is mostly OK but that relies on a contrived and annoying trick ending. It's about an old spacer, about to retire, and a young kid who is bored by the old man's tales of his home, Lulungomeena, and frustrated by the old man's claim to have once been a ready gambler, who gave up the habit. The kid wants to get a chance at the old man's savings, and also to shut him up. He finally baits the older man into a large bet ... and then the trick ending. One interesting detail is that the story is narrated by another older spaceman, who identifies himself as a Dorsai. The earliest story Miller/Contento list as part of the Childe Cycle is "Act of Creation" (Satellite, April 1957). This one seems at least linked (or perhaps part of a beta version of some sort).

Orbit, July-August 1954

"Fellow of the Bees", by Gordon R. Dickson (7700 words) -- very slight but modestly entertaining. A somewhat implausibly vicious Empire comes to a remote planet to press gang crewmembers for their space navy. Most implausibly of all, they plan to press gang EVERY adult between about 20 and 60! The day is saved by the good fortune that the politically appointed admiral of the fleet is a bee lover, and by some implausibly brilliant space navy tactics masterminded by an old lady using the planet's merchant fleet.

Venture, March 1957

“Friend’s Best Man” is a Gordon Dickson sociological set-up story … really a very Campbellian sort of thing. A rich man comes to an isolated frontier planet to meet an old friend, and learns that the friend has been murdered by a local nogoodnik. And that despite the dead man being universally popular, and the nogoodnik largely reviled, and the facts of the case not being in dispute, nothing is being done about it. The reason soon becomes obvious – the planet is labor-starved, and they can’t afford to lose the work done by the bad guy. The only solution is for the rich visitor to replace him – then justice can be done, and the bad guy punished. But will the rich guy have the balls to give up his easy life for the hard work of a frontier planet? Dickson is here straining to make a point, a point that frankly I don’t believe for a second. The strains of the setup show, and there is no examination of the ultimate stresses – and resulting loss of productivity – that such a system would cause.

Astounding, December 1957

The other story that presents the humans are inherently superior idea, much more explicitly, is Dickson's "Danger -- Human!". (Silverberg's story, to give it its due, doesn't really suppose that humans are inherently superior, just that some sort of local historical accident has resulted in humanity being ahead of the nearby aliens in development.) In "Danger -- Human!" an alien group is monitoring Earth. It seems that humans are the descendents of a race that two or three times before has risen from obscurity to dominate the Galaxy, not to the benefit of the rest of the intelligent races. One of the monitoring guys decides to kidnap an human, a New Hampshire farmer, to study him and figure out if humans are still dangerous. Bad idea ... (as we could guess immediately). The main problem is that the human superiority is essentially asserted, not proven, unless we are to conclude from a final revelation (unless I misunderstood it) that the guy broke through an impenetrable field of some sort that humans have psi powers. (Which would really make the story stupid.)

Analog, August 1974

This is the first SF magazine I ever bought, from the newsstand at Alton Drugs in Naperville, IL, sometime in July of 1974. I'd been reading SF from the library with great dedication for a couple of years by then, and reading anthologies like The Science Fiction Hall of Fame and the Nebula Award Stories collections had shown me that there were magazines that published the stuff.

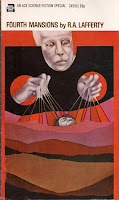

That day there were three magazines next to each other, the August issues of Analog, Galaxy, and F&SF. I bought the Analog first because it still had a certain reputation in my mind -- derived mostly from Campbell's 1940s "Golden Age". (I also liked the John Schoenherr cover.) I read through it quickly, and the next day I bought Galaxy, and the day after I bought F&SF.

The cover story is "Enter a Pilgrim", by Gordon R. Dickson. It tells of Shane Evert, a young man who works as a translator for the alien ruler of Earth -- Earth having been conquered three years before by the huge and technologically superior Aalaag. Shane dreams of some hero leading a resistance to the Aalaag, but on this day he witness the brutal execution of a man who had defended his wife from a careless young Aalaag. Later, a bit drunk, Shane is accosted by three human outlaws, but easily kills them all -- and in the mixture of shame and triumph he feels, something clicks, and the takes what (I can tell) will be the first steps of resistance to the Aalaag. Even at 14 I could see that this was not a complete story -- and indeed, three more stories followed (two in Analog, one in the anthology/magazine Far Frontiers), and they were fixed up into a novel, Way of the Pilgrim (1987). This took a surprisingly long time -- the other stories didn't appear until 1980 and 1985, and I never actually have read the novel, though I'm fairly sure I know the basic plot!

(That August 1974 Galaxy also features a story that is basically an appendage to a novel -- Ursula K. Le Guin's "The Day Before the Revolution", which to be fair isn't part of The Dispossessed, and works fine by itself. And I should note that Lester Del Rey picked the Dickson story for his Best of the Year volume.)

Cosmos, July 1977

"Monad Gestalt", Dickson's novella, is actually part of his novel Time Storm. It reads very much like a novel excerpt -- it's not very successful standing alone. The central idea of Time Storm is neat enough -- Earth (and, it turns out, the whole universe) is divided by "windwalls" into different times -- if you pass through a wall (which may be stationary or moving) you will end up in the same geographical location but at another time. Our hero (the first person narrator) is leading a group of people, including a few violent toughs, a scientifically-oriented man, a teenaged girl, a woman named Marie with a four year old daughter, and a tame leopard. The narrator has claimed Marie as "his woman" but doesn't love her. The teenager is attracting the attention of the leader of the toughs, a man named Tek. The group is trying to find a spot in the future that might hold a clue to the origin of the time storm. Indeed, they do eventually find a deserted future city -- deserted but for one inhabitant, an "avatar" of an alien intelligence. Guided by the alien plus a lot of totally ridiculous mumbo-jumbo, our hero finds another location with a sort of computer/gestalt connection, which will allow him to link with the other minds in his group and become a sort of supermind, able to deflect the time storm at least locally.

Faugh! Dickson sets up an intriguing premise in the time storm and resolves it with authorial fiat. (And stupid coincidence -- the narrator needs exactly eight people in his "gestalt" to gain full power. But there are only seven adults in his group. Not to worry -- the four year old can be combined with a genetically engineered ape that just happens to be nearby to provide slot number 8!) Add a very creepy romance that doesn't even have any emotional force -- the narrator all of a sudden just realizes that he wants the teenaged (young teenaged -- not much older than 14) girl for his own. To be fair, some of the problems I had with this story may well be the result of abridgement to novella length -- the full novel might allow more convincing development of some of these things.