As with many of these writers, my reviews only cover late work -- I'm not discussing some of Howard Waldrop's spectacular stories from the '80s and '90s. But, be that as it may -- Howard turns 73 today, and here's a look at the stories I've reviewed over my time at Locus, not to mention on early piece for Shayol.

Review of Shayol #7

Waldrop's story, "What Makes Hieronymus Run?", is a weird one -- quel surprise, eh? It's about a couple time traveling to 16th Century Holland. But instead of tulip growers and the Duke of Alba, they find themselves in scenes from paintings, eventually including, of course, a painting by Bosch. Pretty good stuff, not quite Waldrop at his best, though. (It didn't really advance enough beyond simply presenting the neat idea.)

Locus, November 2003

In Sci Fiction for October I also enjoyed Howard Waldrop's "D=RxT", though it doesn't seem to be SF: a loving and honest story about boys (and a girl) in the 50s racing pedal cars, and a challenge from "Rocket Boy".

Locus, October 2004

Sci Fiction in September offers a short story by Howard Waldrop, "The Wolf-man of Alcatraz", which, in a characteristically Waldropian way, takes a goofy idea and makes it seem natural: what if the "Birdman of Alcatraz" was a "Wolf-man" – a werewolf. His evocation of the prisoner's life, buttressed with details like his obsession with the moon, is very nicely done, though almost too straightforward.

Locus, December 2005

In Sci Fiction in November there is a pretty good Howard Waldrop story, “The Horse of a Different Color (That You Rode In On)”, about an unknown (to us) Marx Brother, Manny Marks, the death of vaudeville, and, particularly, a mysterious vaudeville act and their quest.

Locus, January 2006

Finally, in the December Sci Fiction, Howard Waldrop offers one of his best recent stories, “The King of Where-I-Go”. Waldrop’s recent territory has been the American 20th Century, ever viewed from just slightly skewed viewpoints: obscure alternate histories, or in this case a very personal bit of time travel. The story concerns a Texas boy and his younger sister. They spend summers with relatives in Alabama, while their parents, in the end unsuccessfully, try to work out marital problems. Then the sister gets polio, surviving because of her Aunt’s experience. She is slightly handicapped, and perhaps changed in another way, as she ends up participating in the Duke University psychic experiments. The story has a definite SFnal twist, but at its heart it is a pitch perfect portrayal of a mid-20th century childhood in the American South.

Review of Fast Ships and Black Sails (Locus, December 2008)

In “Avast, Abaft”, Howard Waldrop mashes up H. M. S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance to delightful effect.

Review of Warriors (Locus, May 2010)

The best of the other entries comes from Howard Waldrop. “Ninieslando” is set during World War I. A British soldier is injured in No Man’s Land, between the lines, and wakes up in a mysterious place, full of Esperanto speakers. (Fortuitously, he had been an Esperanto enthusiast prior to the war.) The story turns on the Esperantist dream of human unity arising from a common language – and turns again, quite bitterly, on the constant ability of humans to find differences for no particular reason. (It’s critical, I suppose, for such a story to be set in the relatively senseless “Great War” rather than in the Second World War.) The story is only marginally fantastical – it’s more a sort of Secret History, but the conception of the existence and location of the Esperantist refuge is pure Waldropian loopiness of the sort that makes it clearly unfair to call it loopy – rather, it’s inspired.

Locus, January 2014

In Old Mars my favorite comes from Howard Waldrop. “The Dead Sea-Bottom Scrolls (A Recreation of Oud’s Journey by Slimshang from Tharsis to Solis Lacus, by George Weeton, Fourth Mars Settlement Wave, 1981)” is, as the title tells us, told at multiple levels – it's a later edition of the account of an early Martian settler reenacting an old Martian's journey as his journal described it … clever, moving, believable, and mysterious.

Sunday, September 15, 2019

Saturday, September 14, 2019

Birthday Review: Stories of Steve Rasnic Tem

I first encountered Steve Rasnic Tem in the little-remembered anthology Other Worlds 1 -- a fantasy offshoot of Roy Torgeson's original anthology series Chrysalis. (Chrysalis and Other Worlds never received the notice that anthologies like the Universe and New Dimensions books did, but they were a worthwhile and different set of books, featuring a noticeably different set of regular writers.) Over the years he (and also his late wife, Melanie Tem) slowly developed for me a reputation as reliably intriguing and original short story writers. Steve Rasnic Tem has published several novels (a couple in collaboration with Melanie), but he still seems primary a short fiction writer, and a very good one. Today is his birthday, and in his honor here's a look stories of his I've reviewed for Locus. (Two of them, "Invisible" and "A Letter From the Emperor" were reprinted in my Best of the Year books, and I recommend them very highly, especially "A Letter From the Emperor", an exceptional story that I think deserved a lot more notice than it got.)

Locus, April 2005

I found Steve Rasnic Tem's "Invisible" (Sci Fiction) quite painful (in a good way): the story of a couple who seem to be growing literally invisible as they become socially invisible. This is, evidently, that sort of fantasy that uses its fantastic element as straightforward metaphor for a "mundane" central theme -- and it does so very well, as we see the viewpoint character's co-workers snubbing him, his daughter failing to call, and his wife's evanescing.

Locus, December 2008

At Asimov’s for December, Melanie Tem and Steve Rasnic Tem offer “In Concert”, a moving story of an aging woman who has, all her life, telepathically sensed the thoughts of others – sometimes those close to her, sometimes people across the world. Now she lives alone, close to death, and she begins to sense the thoughts of an astronaut lost in space. She also learns something about her possibly suicidal great-grandson, and in the end, much is lost – in the natural way of things – but hope remains.

Locus, October 2009

Black Static’s version of “horror” probably fits my taste as well as any horror magazine. At the August/September issue I enjoyed Steve Rasnic Tem’s “Charles”, a deadpan tale of a mother telling her long dead son that it’s really not right for dead people to marry – the story is at first funny, but it closes on an effectively sad note.

Locus, January 2010

“A Letter from the Emperor”, by Steve Rasnic Tem, is the outstanding piece from the January Asimov’s. Jacob is a messenger for a Galactic Empire. His partner has just committed suicide as they come to an isolated planet, long out of contact with what seems an only tenuously in control Emperor. His guilt over his failure to understand his late partner combines with his concern for the aging governor of this planet, who is desperate for approval from his Emperor … and what results is a letter that perhaps says more about we readers and our nostalgia for things like Galactic Empires and noble adventures than anything else.

Locus, January 2011

Then Steve Rasnic Tem’s “Visitors” (Asimov's, January) tells of a future punishment, as an old couple are shown visiting their son, who is confined rather horribly in a sort of suspended animation. It seems a way of avoiding the death penalty without really avoiding it, and the implications are quite disturbing.

Beneath Ceaseless Skies for October 14 had some strong work, including a neat, funny, original wizard’s apprentice type story from Steve Rasnic Tem, “Dying on the Elephant Road”, about a lovelorn young man who gets himself killed trying to protect the woman he loves (who doesn’t know him), only to be restored (sort of) by a wizard;

Locus, April 2005

I found Steve Rasnic Tem's "Invisible" (Sci Fiction) quite painful (in a good way): the story of a couple who seem to be growing literally invisible as they become socially invisible. This is, evidently, that sort of fantasy that uses its fantastic element as straightforward metaphor for a "mundane" central theme -- and it does so very well, as we see the viewpoint character's co-workers snubbing him, his daughter failing to call, and his wife's evanescing.

Locus, December 2008

At Asimov’s for December, Melanie Tem and Steve Rasnic Tem offer “In Concert”, a moving story of an aging woman who has, all her life, telepathically sensed the thoughts of others – sometimes those close to her, sometimes people across the world. Now she lives alone, close to death, and she begins to sense the thoughts of an astronaut lost in space. She also learns something about her possibly suicidal great-grandson, and in the end, much is lost – in the natural way of things – but hope remains.

Locus, October 2009

Black Static’s version of “horror” probably fits my taste as well as any horror magazine. At the August/September issue I enjoyed Steve Rasnic Tem’s “Charles”, a deadpan tale of a mother telling her long dead son that it’s really not right for dead people to marry – the story is at first funny, but it closes on an effectively sad note.

Locus, January 2010

“A Letter from the Emperor”, by Steve Rasnic Tem, is the outstanding piece from the January Asimov’s. Jacob is a messenger for a Galactic Empire. His partner has just committed suicide as they come to an isolated planet, long out of contact with what seems an only tenuously in control Emperor. His guilt over his failure to understand his late partner combines with his concern for the aging governor of this planet, who is desperate for approval from his Emperor … and what results is a letter that perhaps says more about we readers and our nostalgia for things like Galactic Empires and noble adventures than anything else.

Locus, January 2011

Then Steve Rasnic Tem’s “Visitors” (Asimov's, January) tells of a future punishment, as an old couple are shown visiting their son, who is confined rather horribly in a sort of suspended animation. It seems a way of avoiding the death penalty without really avoiding it, and the implications are quite disturbing.

Beneath Ceaseless Skies for October 14 had some strong work, including a neat, funny, original wizard’s apprentice type story from Steve Rasnic Tem, “Dying on the Elephant Road”, about a lovelorn young man who gets himself killed trying to protect the woman he loves (who doesn’t know him), only to be restored (sort of) by a wizard;

Friday, September 13, 2019

Birthday Review: Olympiad, by Tom Holt

Last year on Tom Holt's birthday I posted a selection of my reviews of K. J. Parker's short fiction. So this year surely it makes sense to post a review of a Tom Holt book! This is one of several blackly comic historical novels he wrote, one of which, The Walled Orchard (originally published in two volumes as Goat Song/The Walled Orchard) is in my opinion one of the best historical novels of the past few decades. (I posted my review of that diptych here.) Alsd, Olympiad isn't as good as that, but it's enjoyable enough, and it's the only other Holt novel on which I had a review ready to post.

Olympiad, by Tom Holt

a review by Rich Horton

Tom Holt wrote an historical novel in two volumes called The Walled Orchard (separately Goat Song and The Walled Orchard), set in Greece at the time of Aristophanes. It is one of my favorite historical novels ever -- a deeply bitter story about the folly of war and the folly of men, very blackly funny, very moving. It stands out among his amusing but rather slight humourous fantasies like a redwood among daisies. He has written two more historical novels set in Greece: a loose sequel to The Walled Orchard called Alexander at the World's End, and a story about the origins of the Olympic Games, Olympiad, published in 2000. Both are broadly similar in tone to The Walled Orchard -- perhaps a touch lighter -- but while they are decent work they are no patch on it.

Tom Holt wrote an historical novel in two volumes called The Walled Orchard (separately Goat Song and The Walled Orchard), set in Greece at the time of Aristophanes. It is one of my favorite historical novels ever -- a deeply bitter story about the folly of war and the folly of men, very blackly funny, very moving. It stands out among his amusing but rather slight humourous fantasies like a redwood among daisies. He has written two more historical novels set in Greece: a loose sequel to The Walled Orchard called Alexander at the World's End, and a story about the origins of the Olympic Games, Olympiad, published in 2000. Both are broadly similar in tone to The Walled Orchard -- perhaps a touch lighter -- but while they are decent work they are no patch on it.

Olympiad is framed as a story told by two aging brothers in about 750 BC concerning the time more than a quarter century earlier that they got themselves stuck traveling around the Pelopennese recruiting athletes for what would become the Olympics. They are telling the story to a bored Phoenician trader who in his turn is trying to convince the Greeks of the value of this newfangled thing the Phoenicians have invented, where you make scratches on pieces of clay or something to help you remember things. Much of the thematic burden, then, is Holt's contention that we are witnessing the invention of history.

The main story involves the two brothers, along with their sister and a couple more people, being sent on a mission to find a bunch of athletes to meet at Olympus for an unheard of concept: Funeral Games without a Funeral. The idea is to arrange for their King's worthless son to look good doing something, because he's apparently pretty bad at everything else, but OK at some athletic events. Unfortunately, another faction wishes to obstruct them, and goes around badmouthing them at the various cities they visit, sometimes in quite evil fashion.

They eventually run into a wanderer who claims to be the unfairly deposed prince of an island city. And to their horror their sister falls for him, which makes it tricky when he turns out to be a jerk. Plus they don't believe his story. And some of the cities they visit are gone, and some aren't interested, and so on ... pretty much its a story of (fairly amusing) abject failure. Which is to say it's very cynical. One of my problems with it was that there are no admirable characters. I know that's a lame complaint, but it really is hard to warm to a book where no one at all is really likable.

Holt's skill is clear, and he gets off plenty of very funny lines and sets up plenty of (often painfully) funny situations, but I thought it only a fitfully enjoyable book. It's odd -- much of it is funny, much of it is penetratingly observed and sensible, the characters are believably portrayed (and seem consistently not people of our time) - it's really quite well done. It just didn't fully work for me.

Olympiad, by Tom Holt

a review by Rich Horton

Tom Holt wrote an historical novel in two volumes called The Walled Orchard (separately Goat Song and The Walled Orchard), set in Greece at the time of Aristophanes. It is one of my favorite historical novels ever -- a deeply bitter story about the folly of war and the folly of men, very blackly funny, very moving. It stands out among his amusing but rather slight humourous fantasies like a redwood among daisies. He has written two more historical novels set in Greece: a loose sequel to The Walled Orchard called Alexander at the World's End, and a story about the origins of the Olympic Games, Olympiad, published in 2000. Both are broadly similar in tone to The Walled Orchard -- perhaps a touch lighter -- but while they are decent work they are no patch on it.

Tom Holt wrote an historical novel in two volumes called The Walled Orchard (separately Goat Song and The Walled Orchard), set in Greece at the time of Aristophanes. It is one of my favorite historical novels ever -- a deeply bitter story about the folly of war and the folly of men, very blackly funny, very moving. It stands out among his amusing but rather slight humourous fantasies like a redwood among daisies. He has written two more historical novels set in Greece: a loose sequel to The Walled Orchard called Alexander at the World's End, and a story about the origins of the Olympic Games, Olympiad, published in 2000. Both are broadly similar in tone to The Walled Orchard -- perhaps a touch lighter -- but while they are decent work they are no patch on it.Olympiad is framed as a story told by two aging brothers in about 750 BC concerning the time more than a quarter century earlier that they got themselves stuck traveling around the Pelopennese recruiting athletes for what would become the Olympics. They are telling the story to a bored Phoenician trader who in his turn is trying to convince the Greeks of the value of this newfangled thing the Phoenicians have invented, where you make scratches on pieces of clay or something to help you remember things. Much of the thematic burden, then, is Holt's contention that we are witnessing the invention of history.

The main story involves the two brothers, along with their sister and a couple more people, being sent on a mission to find a bunch of athletes to meet at Olympus for an unheard of concept: Funeral Games without a Funeral. The idea is to arrange for their King's worthless son to look good doing something, because he's apparently pretty bad at everything else, but OK at some athletic events. Unfortunately, another faction wishes to obstruct them, and goes around badmouthing them at the various cities they visit, sometimes in quite evil fashion.

They eventually run into a wanderer who claims to be the unfairly deposed prince of an island city. And to their horror their sister falls for him, which makes it tricky when he turns out to be a jerk. Plus they don't believe his story. And some of the cities they visit are gone, and some aren't interested, and so on ... pretty much its a story of (fairly amusing) abject failure. Which is to say it's very cynical. One of my problems with it was that there are no admirable characters. I know that's a lame complaint, but it really is hard to warm to a book where no one at all is really likable.

Holt's skill is clear, and he gets off plenty of very funny lines and sets up plenty of (often painfully) funny situations, but I thought it only a fitfully enjoyable book. It's odd -- much of it is funny, much of it is penetratingly observed and sensible, the characters are believably portrayed (and seem consistently not people of our time) - it's really quite well done. It just didn't fully work for me.

Thursday, September 12, 2019

Ace Double Reviews, 56: Meeting at Infinity, by John Brunner/Beyond the Silver Sky, by Kenneth Bulmer

I just figured it was time to post another of my old Ace Double reviews, this time one by a couple of very prolific Ace Double writers. This is a pretty short review compared to my usual.

Ace Double Reviews, 56: Meeting at Infinity, by John Brunner/Beyond the Silver Sky, by Kenneth Bulmer (#D-507, 1961, $0.35)

a review by Rich Horton

Meeting at Infinity is about 48,000 words long. This Ace publication seems to be its first -- I can find no evidence of earlier serial publication, nor of expansion from a shorter work. It's an odd work for Brunner, to my mind -- it strikes me as almost consciously a pastiche or imitation of someone like Charles Harness (or perhaps A. E. Van Vogt).

I admit I was surprised not to find a serial version, because the book shares with some serials a three part structure, in which the central "paradigm", as it were, changes each part. The novel opens with a policeman chasing a man he believes to be a murderer. The "murderer", Luis Nevada, desperately confronts a prominent man, Ahmed Lyken, with the phrase "Remember Akkilmar", and Lyken rescues him. Lyken, as it happens, has just learned that he is about to lose his franchise for a "Tacket world".

So what's going on? It turns out that the "Tacket Worlds" are alternate Earths. Franchise owners have monopoly control of trade with a given alternate world. This is economically vital for Earth, but dangerous, because in the past a plague came across from a Tacket World. Franchise owners have complete control of their worlds, even to the point of being allowed to shelter murderers. But why is Lyken so interested in "Akkilmar"?

The plot becomes recomplicated. A young street kid, working for a gangster boss, tries to sell his valuable information about Nevada and Lyken's confrontation to his boss, who asks him to find out more. But Lyken is planning to retreat to his Tacket World and fight. And what of Luis Nevada's horribly burned ex-wife and her desire for revenge? And the primitive but mentally powerful people of Akkilmar? And who is the hero of this book anyway?

As I said, Brunner keeps upping the ante, changing our expectations. It's kind of fun, though not terribly convincing at any step. Middle-range early Brunner, on the whole.

Beyond the Silver Sky first appeared, under the same title, in Science Fantasy, #43 (October 1960). The book version may be slightly expanded -- it's about 30,000 words long. I haven't seen the magazine version -- it apparently occupies about 60 pages, which would probably be about 27,000 words (but I may be off in that count).

It is set in a far future undersea society. The human residents of the society are somewhat adapted to undersea life -- they have gills, for example -- but they rigorously cull further mutations, such as webfooted children. They are hard-pressed by mysterious foes called the Zammu. They are also facing the dropping of the sea level -- or as they call it, the lowering of the "Silver Sky".

Keston Ochiltree is a young man with scientific training, but a volunteer in the military. He is recruited by his former professor for a mission to investigate what lies "beyond the silver sky". The novel simply tells of his expedition -- along with two professors, another young man, and two young women who are there only to provide not very convincing love interests for the young men. The expedition itself is also not very interesting, as no reader will be in the slightest surprised by the discoveries. (Gasp! Humans once lived out of the sea! Amazing!) The novel also ends quite abruptly, with no very satisfying resolution to the potentially interesting questions raised ("What are the Zammu?" "What will humans do in response to the lowered sea level" etc.) I wonder if Bulmer wrote either predecessors or successors to this story.

Ace Double Reviews, 56: Meeting at Infinity, by John Brunner/Beyond the Silver Sky, by Kenneth Bulmer (#D-507, 1961, $0.35)

a review by Rich Horton

|

| (Covers by Ed Emswhiller and John Schoenherr (in a very Richard Powers-esque mode)) |

I admit I was surprised not to find a serial version, because the book shares with some serials a three part structure, in which the central "paradigm", as it were, changes each part. The novel opens with a policeman chasing a man he believes to be a murderer. The "murderer", Luis Nevada, desperately confronts a prominent man, Ahmed Lyken, with the phrase "Remember Akkilmar", and Lyken rescues him. Lyken, as it happens, has just learned that he is about to lose his franchise for a "Tacket world".

So what's going on? It turns out that the "Tacket Worlds" are alternate Earths. Franchise owners have monopoly control of trade with a given alternate world. This is economically vital for Earth, but dangerous, because in the past a plague came across from a Tacket World. Franchise owners have complete control of their worlds, even to the point of being allowed to shelter murderers. But why is Lyken so interested in "Akkilmar"?

The plot becomes recomplicated. A young street kid, working for a gangster boss, tries to sell his valuable information about Nevada and Lyken's confrontation to his boss, who asks him to find out more. But Lyken is planning to retreat to his Tacket World and fight. And what of Luis Nevada's horribly burned ex-wife and her desire for revenge? And the primitive but mentally powerful people of Akkilmar? And who is the hero of this book anyway?

As I said, Brunner keeps upping the ante, changing our expectations. It's kind of fun, though not terribly convincing at any step. Middle-range early Brunner, on the whole.

Beyond the Silver Sky first appeared, under the same title, in Science Fantasy, #43 (October 1960). The book version may be slightly expanded -- it's about 30,000 words long. I haven't seen the magazine version -- it apparently occupies about 60 pages, which would probably be about 27,000 words (but I may be off in that count).

It is set in a far future undersea society. The human residents of the society are somewhat adapted to undersea life -- they have gills, for example -- but they rigorously cull further mutations, such as webfooted children. They are hard-pressed by mysterious foes called the Zammu. They are also facing the dropping of the sea level -- or as they call it, the lowering of the "Silver Sky".

Keston Ochiltree is a young man with scientific training, but a volunteer in the military. He is recruited by his former professor for a mission to investigate what lies "beyond the silver sky". The novel simply tells of his expedition -- along with two professors, another young man, and two young women who are there only to provide not very convincing love interests for the young men. The expedition itself is also not very interesting, as no reader will be in the slightest surprised by the discoveries. (Gasp! Humans once lived out of the sea! Amazing!) The novel also ends quite abruptly, with no very satisfying resolution to the potentially interesting questions raised ("What are the Zammu?" "What will humans do in response to the lowered sea level" etc.) I wonder if Bulmer wrote either predecessors or successors to this story.

Wednesday, September 11, 2019

Birthday Review: Stories of Pat Cadigan

Yesterday was Pat Cadigan's birthday. She has been a really impressive SF writer for a long time. And we shouldn't forget that early in her career she edited one of the great semi-professional magazines ever. In her honor, then, here's a selection of my Locus reviews of her short fiction, but beginning with a look at an issue of her lovely magazine Shayol (complete with one of her stories.)

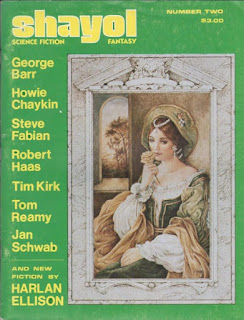

Review of Shayol #2, February 1978

I thought I had better cover a 70s issue of Shayol, if my goal was to cover 70s magazines. This issue is the second. To my taste it isn't quite as nice looking as #7, but still a very professionally produced product, as well done as any SF magazine ever.

The cover is by Robert Haas, called "Beauty", from a series of illustrations of "Beauty and the Beast". There is an interior black and white section with a few more of Haas's "Beauty and the Beast" illos. There is one more special art feature, called "Shayol", by Vikki Marshall -- four full-page drawings based on Cordwainer Smith stories. It wasn't much to my taste. Another illustration-oriented feature is an interview -- a long one -- with Tim Kirk. Interior illustrations for the stories are by Haas, Marshall, Jan Schwab, Clyde Caldwell, and Debora Whitehouse, with George Barr contributing a nice picture of Kirk. And the inside front cover features a Steve Fastner/Randall Larson picture. And there is a full page Kirk cartoon.

Other features include Harlan Ellison's famous open letter to attendees of Iguanacon, the World SF Convention in Arizona for which he was GOH. As a protest against Arizona's failure to ratify the ERA, he was refusing to spend any money in the state, while still honoring his commitment to the Convention. Steve Utley has a poem, "Rex and Regina", about Tyrannosaurs. Phillip Bolick's brief essay "Thick Thews and Busty Babes" (illustrated by Howard Chaykin) criticizes the narrowness of focus and lack of humor in Robert E. Howard and imitators. Book Reviews, by Marty Ketchum, are of The Futurians, The Shining, and Rime Isle. The editorial has one section by Arnie Fenner, much of it given to a rant about the poor printing quality of the first issues, and one section by Pat Cadigan, about Brooke Shields (then 12) and child porn. And there is a Contributors section with brief profiles and a few photos.

The fiction includes three short stories. Harlan Ellison's "Opium" (1400 words) is about a plain woman committing suicide, rescued by the Seven Dwarves who convince her to live in the "real world", i.e. a wet dream. Minor stuff. Terry Matz's "Sport" (5000 words) is not bad. Aliens have taken over Earth and bred humans for their ideas of beauty (i.e. grotesqueness) and lack of intelligence. One alien has bred one mutant for intelligence -- this "sport" tells the story, which concerns a captured wild human who his owner wants to breed to him. (This seems to have been Matz's only publication.) Tom Reamy had just died, and there is an obituary accompanying his story, "Waiting for Billy Star" (2400 words). Reamy lived in Kansas City (I had always thought him a Texan, and he was a native of Texas), and was apparently very close to Cadigan and Fenner (Shayol was based in KC). This story is a sad piece about a woman in love with a no-account rodeo cowboy who dumps her. She waits for him forlornly at a truck stop, then she hears that he has died ... Neat little story.

William Wallace's "The Mare" is a shortish novelette, at about 7700 words. It's horror, and quite well executed but not my sort of thing. The inevitableness of horror I find tiresome -- you know from the start exactly how it will work out. This story is about a young man, living with a woman on his family's haunted farm in East Texas. He remembers his grandfather's horrible death, and he has dreams, and ... well, you know where it's going. And as I said, it's well enough done -- professionally written and all, but what's the POINT? (This is one of only 2 stories Wallace seems to have published, not counting four collaborations with Joseph Pumilia as "M. M. Moamrath".)

Finally, Cadigan contributes a novella, "Death From Exposure" (20,000 words). Nice to see a story so long in a semipro magazine. Though I must say, the story probably should have been cut about in half. It's about two women cops, who are mostly assigned to trivial things like arresting flashers. (SF reading protocols messed me up here -- for a while I thought "flashers" might be referring to some futuristic crime, but no, the story is apparently contemporary in setting, and the "flashers" are just dirty old men in raincoats.) Then a woman is turned to stone. They investigate, at first refusing to believe it's anything but a prank. At long last they are convinced something real is going on, after some more "statues" turn up. And the whole thing is related to flashers. The point of the thing is to reveal the characters of the two partners, and the final revelation is believable and pretty affecting, but the story takes too long getting there. Still, decent work. The story does not seem to have been reprinted, unless fairly recently.

Locus, September 2005

Sci Fiction for August features Pat Cadigan's "Is There Life After Rehab?" -- a pure delight. The opening line is a killer, the real meaning taking some time to come clear. I think the story is best appreciated cold so I'll say nothing in particular – it is indeed about rehab, and about the lure of addiction – a special sort of addiction in this case. I really liked it.

Review of The Del Rey Book of Science Fiction (Locus, April 2008)

Pat Cadigan’s “Jimmy” is a moving story of a girl growing up in the ‘60s, and her friend Jimmy, who is passed around from worthless relative to worthless relative – finally escaping, perhaps, after revealing to her his distressing secret.

Locus, April 2009

Ellen Datlow’s new anthology, Poe, includes stories “inspired” by Edgar Allan Poe … sometimes riffing on stories or poems, other times simply borrowing Poe’s atmospheres and themes, once or twice even featuring Poe as a character. It’s a strong book throughout. I particularly liked Pat Cadigan’s “Truth and Bone”, about an extended family of people with unusual “knowledge”. A different sort of knowledge. Hannah’s mother, for example, knows how to fix things. And her aunt knows when you’re lying. But Hannah realizes early that her talent, her knowledge, will be something a lot scarier and a lot less useful. And the story shows why in believable and wrenching terms.

Review of Is Anybody Out There? (Locus, June 2010)

Pat Cadigan, in “The Taste of Night”, tells of a woman who has become a street person in part because she is convinced that aliens are on the way, and are communicating with her through an extra sense she is developing. It is heartbreaking in its portrayal of her decline, and her husband’s despair – but it might just be hopeful, if we can believe her obsession is real.

Review of Urban Fantasy (Locus, August 2011)

Foreign cities get a look in too -- Pat Cadigan’s “Picking Up the Pieces” is told by one of five sisters, about the youngest (by a wide margin), named Quinn. Quinn falls in love with a German man, but has her heart broken when he leaves her as the Wall is about to come down, in late 1989. Quinn follows him, and her sister follows her, and they learn something striking about her erstwhile boyfriend’s family.

Locus, December 2012

Strahan also gives us a new anthology of stories set in the relatively near future Solar System, Edge of Infinity, which has a plethora of neat pieces. I had two favorites. “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi”, by Pat Cadigan, is set in Jupiter's orbit among the various workers, most of whom have had themselves altered to forms more useful in space. It concerns the legal travails of an unaltered woman who wants to alter herself after an injury – which of course reflects also the legal and political situation of everyone out there.

Review of Shayol #2, February 1978

|

| (Cover by Robert Haas) |

The cover is by Robert Haas, called "Beauty", from a series of illustrations of "Beauty and the Beast". There is an interior black and white section with a few more of Haas's "Beauty and the Beast" illos. There is one more special art feature, called "Shayol", by Vikki Marshall -- four full-page drawings based on Cordwainer Smith stories. It wasn't much to my taste. Another illustration-oriented feature is an interview -- a long one -- with Tim Kirk. Interior illustrations for the stories are by Haas, Marshall, Jan Schwab, Clyde Caldwell, and Debora Whitehouse, with George Barr contributing a nice picture of Kirk. And the inside front cover features a Steve Fastner/Randall Larson picture. And there is a full page Kirk cartoon.

Other features include Harlan Ellison's famous open letter to attendees of Iguanacon, the World SF Convention in Arizona for which he was GOH. As a protest against Arizona's failure to ratify the ERA, he was refusing to spend any money in the state, while still honoring his commitment to the Convention. Steve Utley has a poem, "Rex and Regina", about Tyrannosaurs. Phillip Bolick's brief essay "Thick Thews and Busty Babes" (illustrated by Howard Chaykin) criticizes the narrowness of focus and lack of humor in Robert E. Howard and imitators. Book Reviews, by Marty Ketchum, are of The Futurians, The Shining, and Rime Isle. The editorial has one section by Arnie Fenner, much of it given to a rant about the poor printing quality of the first issues, and one section by Pat Cadigan, about Brooke Shields (then 12) and child porn. And there is a Contributors section with brief profiles and a few photos.

The fiction includes three short stories. Harlan Ellison's "Opium" (1400 words) is about a plain woman committing suicide, rescued by the Seven Dwarves who convince her to live in the "real world", i.e. a wet dream. Minor stuff. Terry Matz's "Sport" (5000 words) is not bad. Aliens have taken over Earth and bred humans for their ideas of beauty (i.e. grotesqueness) and lack of intelligence. One alien has bred one mutant for intelligence -- this "sport" tells the story, which concerns a captured wild human who his owner wants to breed to him. (This seems to have been Matz's only publication.) Tom Reamy had just died, and there is an obituary accompanying his story, "Waiting for Billy Star" (2400 words). Reamy lived in Kansas City (I had always thought him a Texan, and he was a native of Texas), and was apparently very close to Cadigan and Fenner (Shayol was based in KC). This story is a sad piece about a woman in love with a no-account rodeo cowboy who dumps her. She waits for him forlornly at a truck stop, then she hears that he has died ... Neat little story.

William Wallace's "The Mare" is a shortish novelette, at about 7700 words. It's horror, and quite well executed but not my sort of thing. The inevitableness of horror I find tiresome -- you know from the start exactly how it will work out. This story is about a young man, living with a woman on his family's haunted farm in East Texas. He remembers his grandfather's horrible death, and he has dreams, and ... well, you know where it's going. And as I said, it's well enough done -- professionally written and all, but what's the POINT? (This is one of only 2 stories Wallace seems to have published, not counting four collaborations with Joseph Pumilia as "M. M. Moamrath".)

Finally, Cadigan contributes a novella, "Death From Exposure" (20,000 words). Nice to see a story so long in a semipro magazine. Though I must say, the story probably should have been cut about in half. It's about two women cops, who are mostly assigned to trivial things like arresting flashers. (SF reading protocols messed me up here -- for a while I thought "flashers" might be referring to some futuristic crime, but no, the story is apparently contemporary in setting, and the "flashers" are just dirty old men in raincoats.) Then a woman is turned to stone. They investigate, at first refusing to believe it's anything but a prank. At long last they are convinced something real is going on, after some more "statues" turn up. And the whole thing is related to flashers. The point of the thing is to reveal the characters of the two partners, and the final revelation is believable and pretty affecting, but the story takes too long getting there. Still, decent work. The story does not seem to have been reprinted, unless fairly recently.

Locus, September 2005

Sci Fiction for August features Pat Cadigan's "Is There Life After Rehab?" -- a pure delight. The opening line is a killer, the real meaning taking some time to come clear. I think the story is best appreciated cold so I'll say nothing in particular – it is indeed about rehab, and about the lure of addiction – a special sort of addiction in this case. I really liked it.

Review of The Del Rey Book of Science Fiction (Locus, April 2008)

Pat Cadigan’s “Jimmy” is a moving story of a girl growing up in the ‘60s, and her friend Jimmy, who is passed around from worthless relative to worthless relative – finally escaping, perhaps, after revealing to her his distressing secret.

Locus, April 2009

Ellen Datlow’s new anthology, Poe, includes stories “inspired” by Edgar Allan Poe … sometimes riffing on stories or poems, other times simply borrowing Poe’s atmospheres and themes, once or twice even featuring Poe as a character. It’s a strong book throughout. I particularly liked Pat Cadigan’s “Truth and Bone”, about an extended family of people with unusual “knowledge”. A different sort of knowledge. Hannah’s mother, for example, knows how to fix things. And her aunt knows when you’re lying. But Hannah realizes early that her talent, her knowledge, will be something a lot scarier and a lot less useful. And the story shows why in believable and wrenching terms.

Review of Is Anybody Out There? (Locus, June 2010)

Pat Cadigan, in “The Taste of Night”, tells of a woman who has become a street person in part because she is convinced that aliens are on the way, and are communicating with her through an extra sense she is developing. It is heartbreaking in its portrayal of her decline, and her husband’s despair – but it might just be hopeful, if we can believe her obsession is real.

Review of Urban Fantasy (Locus, August 2011)

Foreign cities get a look in too -- Pat Cadigan’s “Picking Up the Pieces” is told by one of five sisters, about the youngest (by a wide margin), named Quinn. Quinn falls in love with a German man, but has her heart broken when he leaves her as the Wall is about to come down, in late 1989. Quinn follows him, and her sister follows her, and they learn something striking about her erstwhile boyfriend’s family.

Locus, December 2012

Strahan also gives us a new anthology of stories set in the relatively near future Solar System, Edge of Infinity, which has a plethora of neat pieces. I had two favorites. “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi”, by Pat Cadigan, is set in Jupiter's orbit among the various workers, most of whom have had themselves altered to forms more useful in space. It concerns the legal travails of an unaltered woman who wants to alter herself after an injury – which of course reflects also the legal and political situation of everyone out there.

Monday, September 9, 2019

Birthday Review: Stories of Tony Pi

Today is the birthday of Canadian writer Tony Pi, whose work I have enjoyed for the past decade or more. Here's a set of my reviews of his short fiction for Locus:

Review of Writers of the Future XXIII (Locus, November 2007)

Tony Pi’s “The Stone Cipher” has one of the wildest ideas: statues around the world begin to move, apparently in unison, but very slowly. The story is in the end an ecological message – but a bit too long and with not quite plausible leads.

Locus, January 2008

At the fourth quarter issue of Abyss and Apex I quite enjoyed a long novelette from Tony Pi, “Metamorphoses in Amber”. It’s about a group of immortals who can use amber to facilitate such things as healing and shape-changing (within limits). The narrator, Flea is trying to steal a Faberge egg from the Mantis, another immortal. Flea and Mantis have long been rivals – for example, they were once Little John and the Sheriff of Nottingham, respectively. He steals the egg, but something goes wrong in his escape, and he finds himself becoming female – an irreversible metamorphosis that happens to the immortals for reasons they don’t understand. His search for a cure leads him to the Amber Room, and a very special piece of amber. Colorful and different adventure.

Locus, April 2009

In Ages of Wonder Tony Pi’s “Sphinx!” is a delight, set in a quite alternate history, in which the land of Ys is threatened by a sphinx that a film maker has apparently revived for a new movie. But other things are going on – most notably, perhaps, the jealousy of the movie’s director about his young wife, the movie’s star.

Locus, May 2009

Tony Pi’s “Silk and Shadows” (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, 2/26) is a fine romantic fantasy, about Dominin, who has at last prevailed in battle against the Stormlord who killed his father. But the victory came at a price: a deal with the notoriously treacherous witch Anansya. Dominin has also fallen in love with Anansya’s apprentice Selenja, and that may make the eventual price even higher. All is resolved imaginatively in a well-enacted magical puppet show.

Locus, July 2009

The Spring On Spec has finally arrived, with nice pieces from Jack Skillingstead and Tony Pi. ... Pi’s “Come-From-Aways” is about a linguistics professor in Newfoundland who risks her career – and eventually much more – when she decides that a strange shipwrecked man is really the 11th Century Welsh Prince Madoc.

Locus, May 2010

Alembical 2 is the second in a series of anthologies of novellas... Best is probably “The Paragon Lure”, by Tony Pi, one of several stories he’s written about a group of shapechanging immortals – here the story revolves around a mysterious pearl, and Elizabeth I – and while at times its just a bit too preposterous it moves nicely and is quite a lot of fun.

Locus, May 2014

I haven't mentioned the venerable Canadian magazine On Spec in a while. It continues to produce enjoyable issues. In Winter 2013/2104 I particularly liked Tony Pi's “The Marotte”, a Russian-flavored fantasy about a sorcerer who is judicially murdered by the Patriarch, but who survives in the jester's “marotte” (a stick-puppet), and is able to work with the jester to try to save his beloved Tsarina from the Patriarch's plots;

Locus, November 2014

The September 4 issue of Beneath Ceaseless Skies features two fine entertainments. “No Sweeter Art”, by Tony Pi, is another story of Ao, the candy magician. Ao is engaged by the local magistrate to protect him against a suspected assassination attempt at a Riddle duel. The magistrate is an expert riddle maker. Pi nicely intertwines Ao's ability – to make candy creatures and inhabit them remotely – with a good look at the riddle contest, with dangerous encounters with the gods of the Chinese Zodiac, and with serious concerns about the morality of killing even bad people.

Locus, June 2016

In Beneath Ceaseless Skies I found ... “The Sweetest Skill”, by Tony Pi, his latest story of Ao, whose magic is entwined with “the sweetest skill”: candymaking. In this entry he is charged by Tiger to save the Pale Tigress, guardian of Chengdu, who has been attacked by the Ten Crows gang. Straightforward enough, if hardly easy – but then Dog and Pig get involved, with ramifications, no doubt, for future stories in what’s become a quite enjoyable series.

Locus, June 2017

I quite enjoyed stories in the two April issues of Beneath Ceaseless Skies. In April 27 we get the latest of Tony Pi’s ongoing and very entertaining series about Tangren Ao, a sugar shaper who uses the magic in his candy animals to help people, often at the behest of the animal spirits of the zodiac. In “That Lingering Sweetness” he encounters a pair of curses in a stolen box of tea intended for the Emperor that has somehow fetched up at a local teashop. He must negotiate with Monkey and Goat, who have set the conflicting curses, and at the same time try to find a way to clean up some of the messes resulting from his earlier adventure. Fun stuff.

Review of Writers of the Future XXIII (Locus, November 2007)

Tony Pi’s “The Stone Cipher” has one of the wildest ideas: statues around the world begin to move, apparently in unison, but very slowly. The story is in the end an ecological message – but a bit too long and with not quite plausible leads.

Locus, January 2008

At the fourth quarter issue of Abyss and Apex I quite enjoyed a long novelette from Tony Pi, “Metamorphoses in Amber”. It’s about a group of immortals who can use amber to facilitate such things as healing and shape-changing (within limits). The narrator, Flea is trying to steal a Faberge egg from the Mantis, another immortal. Flea and Mantis have long been rivals – for example, they were once Little John and the Sheriff of Nottingham, respectively. He steals the egg, but something goes wrong in his escape, and he finds himself becoming female – an irreversible metamorphosis that happens to the immortals for reasons they don’t understand. His search for a cure leads him to the Amber Room, and a very special piece of amber. Colorful and different adventure.

Locus, April 2009

In Ages of Wonder Tony Pi’s “Sphinx!” is a delight, set in a quite alternate history, in which the land of Ys is threatened by a sphinx that a film maker has apparently revived for a new movie. But other things are going on – most notably, perhaps, the jealousy of the movie’s director about his young wife, the movie’s star.

Locus, May 2009

Tony Pi’s “Silk and Shadows” (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, 2/26) is a fine romantic fantasy, about Dominin, who has at last prevailed in battle against the Stormlord who killed his father. But the victory came at a price: a deal with the notoriously treacherous witch Anansya. Dominin has also fallen in love with Anansya’s apprentice Selenja, and that may make the eventual price even higher. All is resolved imaginatively in a well-enacted magical puppet show.

Locus, July 2009

The Spring On Spec has finally arrived, with nice pieces from Jack Skillingstead and Tony Pi. ... Pi’s “Come-From-Aways” is about a linguistics professor in Newfoundland who risks her career – and eventually much more – when she decides that a strange shipwrecked man is really the 11th Century Welsh Prince Madoc.

Locus, May 2010

Alembical 2 is the second in a series of anthologies of novellas... Best is probably “The Paragon Lure”, by Tony Pi, one of several stories he’s written about a group of shapechanging immortals – here the story revolves around a mysterious pearl, and Elizabeth I – and while at times its just a bit too preposterous it moves nicely and is quite a lot of fun.

Locus, May 2014

I haven't mentioned the venerable Canadian magazine On Spec in a while. It continues to produce enjoyable issues. In Winter 2013/2104 I particularly liked Tony Pi's “The Marotte”, a Russian-flavored fantasy about a sorcerer who is judicially murdered by the Patriarch, but who survives in the jester's “marotte” (a stick-puppet), and is able to work with the jester to try to save his beloved Tsarina from the Patriarch's plots;

Locus, November 2014

The September 4 issue of Beneath Ceaseless Skies features two fine entertainments. “No Sweeter Art”, by Tony Pi, is another story of Ao, the candy magician. Ao is engaged by the local magistrate to protect him against a suspected assassination attempt at a Riddle duel. The magistrate is an expert riddle maker. Pi nicely intertwines Ao's ability – to make candy creatures and inhabit them remotely – with a good look at the riddle contest, with dangerous encounters with the gods of the Chinese Zodiac, and with serious concerns about the morality of killing even bad people.

Locus, June 2016

In Beneath Ceaseless Skies I found ... “The Sweetest Skill”, by Tony Pi, his latest story of Ao, whose magic is entwined with “the sweetest skill”: candymaking. In this entry he is charged by Tiger to save the Pale Tigress, guardian of Chengdu, who has been attacked by the Ten Crows gang. Straightforward enough, if hardly easy – but then Dog and Pig get involved, with ramifications, no doubt, for future stories in what’s become a quite enjoyable series.

Locus, June 2017

I quite enjoyed stories in the two April issues of Beneath Ceaseless Skies. In April 27 we get the latest of Tony Pi’s ongoing and very entertaining series about Tangren Ao, a sugar shaper who uses the magic in his candy animals to help people, often at the behest of the animal spirits of the zodiac. In “That Lingering Sweetness” he encounters a pair of curses in a stolen box of tea intended for the Emperor that has somehow fetched up at a local teashop. He must negotiate with Monkey and Goat, who have set the conflicting curses, and at the same time try to find a way to clean up some of the messes resulting from his earlier adventure. Fun stuff.

Friday, September 6, 2019

Birthday Review: The Scar, by China Mieville

Birthday Review: The Scar, by China Mieville

Today is China Mieville's 47th birthday. In his honor, then, here's what I wrote way back when about his third novel, The Scar. I should add, perhaps, that two of his later novels are better still: Embassytown and The City and the City are brilliant -- truly two of the best works of fantastika of the 21st century.

The Scar is China Mieville's third novel. His second, Perdido Street Station, was a major success, garnering him a Hugo nomination as well as plenty of critical acclaim and, unless I miss by guess, healthy sales. This new novel is set in the same world as Perdido Street Station, Bas Lag, and as such fits loosely into that vague subgenre sometimes called "Science Fantasy". That novel was set in the huge, corrupt, city of New Crobuzon. This novel opens with mysterious doings in the ocean, and then we meet the noted linguist Bellis Coldwine, who is fleeing New Crobuzon to the colony city of Nova Esperancia. A tenuous linkage to the events of Perdido Street Station is provided by Bellis's reasons for leaving: she was a former lover of the hero of Perdido Street Station, and she fears being rounded up as a potential witness after the rather catastrophic happenings in that book.

The ship carrying Bellis Coldwine (as well as ocean biologist Johannes Tearfly and a group of Remade prisoners including a man named Tanner Sack) does not get very far, though, before it is overtaken by pirates from the mysterious floating city Armada. Bellis, Johannes, and the other passengers and prisoners are taken to Armada, where they are informed they will live the rest of their lives. They cannot leave the floating city, but they will otherwise be allowed full citizenship. Tanner Sack and Johannes accept fairly eagerly, but Bellis is desperate to have a chance to return to her beloved home city. Soon she falls into league with the mysterious Silas Fennec, a spy from New Crobuzon who is as desperate as she to return home, in his case because he has information of a coming attack on their city. It becomes clear that the leaders of Armada are engaged in a mysterious project, and Bellis becomes a key figure when she finds a crucial book in a language that she is a leading expert in. She learns that Armada is planning to harness a huge sea creature called an avanc, and to have the avanc tow the floating city to the dangerous rift in reality called the Scar, where it might be possible to do "Probability Mining". More importantly to her and Fennec, her new influence gives her the chance to get a message Fennec has prepared back to New Crobuzon.

The story takes further twists and turns from there -- it's very intelligently plotted, with the motivations of the characters well portrayed, and with plot elements that seem weak later revealed, after a twist or two, to make much more sense. But it's not the plot that is the key to enjoying the book. The characters are also fascinating. Besides Bellis and Tanner and Fennec, there are such Armadan figures as the Lovers, male and female leaders of Armada's strongest "riding", who scar each other symmetrically during their S&Mish lovemaking; Uther Doul, the dour and enigmatic bodyguard with a sword forged by the creatures who made the Scar, a sword that flickers through multiple possible outcomes, possible paths, at once; and the Brucolac, a vampir, and a fairly conventional one, but still strikingly portrayed.

As in Perdido Street Station, Mieville invents fascinating part-human species, hybrids of humans and other forms, in this book most strikingly the anophelii, mosquito men, and, more scarily and affectingly, mosquito women. In the end it is Mieville's fervent, sometimes overheated, imagination, that drives the book. His descriptions of cruel and dirty places, and odd creatures, are endless intriguing. Yes, he sometimes luxuriates overmuch in grotesquerie, but I suspect any application of discipline to his imagination would lose us more neat visions than we might gain by avoiding the occasional silliness or vulgarness. The book is also a bit too long -- some of this is the author's delight in showing us this or that cool gross notion he has had, but also I think his sense of pace is weak. A fair number of scenes, I think, could readily have been excised or shortened. (Such as most of the grindylow "interludes".) The other weakness is one fairly common in certain fantasy: when so many weird magical things are allowed, on occasion it seems that things happen, or characters gain powers, for reasons of the plot only. But though the book is a bit overlong, it remains compelling reading, and though the magical happenings aren't always fully consistent, they really don't strain suspension of disbelief too much: on the whole, this is another outstanding effort from Mieville. I'd rank it about even with Perdido Street Station, and perhaps slightly better on the grounds that the plot really is worked out quite well, with plenty of surprises and an honest, satisfying, resolution.

Today is China Mieville's 47th birthday. In his honor, then, here's what I wrote way back when about his third novel, The Scar. I should add, perhaps, that two of his later novels are better still: Embassytown and The City and the City are brilliant -- truly two of the best works of fantastika of the 21st century.

The Scar is China Mieville's third novel. His second, Perdido Street Station, was a major success, garnering him a Hugo nomination as well as plenty of critical acclaim and, unless I miss by guess, healthy sales. This new novel is set in the same world as Perdido Street Station, Bas Lag, and as such fits loosely into that vague subgenre sometimes called "Science Fantasy". That novel was set in the huge, corrupt, city of New Crobuzon. This novel opens with mysterious doings in the ocean, and then we meet the noted linguist Bellis Coldwine, who is fleeing New Crobuzon to the colony city of Nova Esperancia. A tenuous linkage to the events of Perdido Street Station is provided by Bellis's reasons for leaving: she was a former lover of the hero of Perdido Street Station, and she fears being rounded up as a potential witness after the rather catastrophic happenings in that book.

The ship carrying Bellis Coldwine (as well as ocean biologist Johannes Tearfly and a group of Remade prisoners including a man named Tanner Sack) does not get very far, though, before it is overtaken by pirates from the mysterious floating city Armada. Bellis, Johannes, and the other passengers and prisoners are taken to Armada, where they are informed they will live the rest of their lives. They cannot leave the floating city, but they will otherwise be allowed full citizenship. Tanner Sack and Johannes accept fairly eagerly, but Bellis is desperate to have a chance to return to her beloved home city. Soon she falls into league with the mysterious Silas Fennec, a spy from New Crobuzon who is as desperate as she to return home, in his case because he has information of a coming attack on their city. It becomes clear that the leaders of Armada are engaged in a mysterious project, and Bellis becomes a key figure when she finds a crucial book in a language that she is a leading expert in. She learns that Armada is planning to harness a huge sea creature called an avanc, and to have the avanc tow the floating city to the dangerous rift in reality called the Scar, where it might be possible to do "Probability Mining". More importantly to her and Fennec, her new influence gives her the chance to get a message Fennec has prepared back to New Crobuzon.

The story takes further twists and turns from there -- it's very intelligently plotted, with the motivations of the characters well portrayed, and with plot elements that seem weak later revealed, after a twist or two, to make much more sense. But it's not the plot that is the key to enjoying the book. The characters are also fascinating. Besides Bellis and Tanner and Fennec, there are such Armadan figures as the Lovers, male and female leaders of Armada's strongest "riding", who scar each other symmetrically during their S&Mish lovemaking; Uther Doul, the dour and enigmatic bodyguard with a sword forged by the creatures who made the Scar, a sword that flickers through multiple possible outcomes, possible paths, at once; and the Brucolac, a vampir, and a fairly conventional one, but still strikingly portrayed.

As in Perdido Street Station, Mieville invents fascinating part-human species, hybrids of humans and other forms, in this book most strikingly the anophelii, mosquito men, and, more scarily and affectingly, mosquito women. In the end it is Mieville's fervent, sometimes overheated, imagination, that drives the book. His descriptions of cruel and dirty places, and odd creatures, are endless intriguing. Yes, he sometimes luxuriates overmuch in grotesquerie, but I suspect any application of discipline to his imagination would lose us more neat visions than we might gain by avoiding the occasional silliness or vulgarness. The book is also a bit too long -- some of this is the author's delight in showing us this or that cool gross notion he has had, but also I think his sense of pace is weak. A fair number of scenes, I think, could readily have been excised or shortened. (Such as most of the grindylow "interludes".) The other weakness is one fairly common in certain fantasy: when so many weird magical things are allowed, on occasion it seems that things happen, or characters gain powers, for reasons of the plot only. But though the book is a bit overlong, it remains compelling reading, and though the magical happenings aren't always fully consistent, they really don't strain suspension of disbelief too much: on the whole, this is another outstanding effort from Mieville. I'd rank it about even with Perdido Street Station, and perhaps slightly better on the grounds that the plot really is worked out quite well, with plenty of surprises and an honest, satisfying, resolution.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)