Today is the birthday of Canadian writer Tony Pi, whose work I have enjoyed for the past decade or more. Here's a set of my reviews of his short fiction for Locus:

Review of Writers of the Future XXIII (Locus, November 2007)

Tony Pi’s “The Stone Cipher” has one of the wildest ideas: statues around the world begin to move, apparently in unison, but very slowly. The story is in the end an ecological message – but a bit too long and with not quite plausible leads.

Locus, January 2008

At the fourth quarter issue of Abyss and Apex I quite enjoyed a long novelette from Tony Pi, “Metamorphoses in Amber”. It’s about a group of immortals who can use amber to facilitate such things as healing and shape-changing (within limits). The narrator, Flea is trying to steal a Faberge egg from the Mantis, another immortal. Flea and Mantis have long been rivals – for example, they were once Little John and the Sheriff of Nottingham, respectively. He steals the egg, but something goes wrong in his escape, and he finds himself becoming female – an irreversible metamorphosis that happens to the immortals for reasons they don’t understand. His search for a cure leads him to the Amber Room, and a very special piece of amber. Colorful and different adventure.

Locus, April 2009

In Ages of Wonder Tony Pi’s “Sphinx!” is a delight, set in a quite alternate history, in which the land of Ys is threatened by a sphinx that a film maker has apparently revived for a new movie. But other things are going on – most notably, perhaps, the jealousy of the movie’s director about his young wife, the movie’s star.

Locus, May 2009

Tony Pi’s “Silk and Shadows” (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, 2/26) is a fine romantic fantasy, about Dominin, who has at last prevailed in battle against the Stormlord who killed his father. But the victory came at a price: a deal with the notoriously treacherous witch Anansya. Dominin has also fallen in love with Anansya’s apprentice Selenja, and that may make the eventual price even higher. All is resolved imaginatively in a well-enacted magical puppet show.

Locus, July 2009

The Spring On Spec has finally arrived, with nice pieces from Jack Skillingstead and Tony Pi. ... Pi’s “Come-From-Aways” is about a linguistics professor in Newfoundland who risks her career – and eventually much more – when she decides that a strange shipwrecked man is really the 11th Century Welsh Prince Madoc.

Locus, May 2010

Alembical 2 is the second in a series of anthologies of novellas... Best is probably “The Paragon Lure”, by Tony Pi, one of several stories he’s written about a group of shapechanging immortals – here the story revolves around a mysterious pearl, and Elizabeth I – and while at times its just a bit too preposterous it moves nicely and is quite a lot of fun.

Locus, May 2014

I haven't mentioned the venerable Canadian magazine On Spec in a while. It continues to produce enjoyable issues. In Winter 2013/2104 I particularly liked Tony Pi's “The Marotte”, a Russian-flavored fantasy about a sorcerer who is judicially murdered by the Patriarch, but who survives in the jester's “marotte” (a stick-puppet), and is able to work with the jester to try to save his beloved Tsarina from the Patriarch's plots;

Locus, November 2014

The September 4 issue of Beneath Ceaseless Skies features two fine entertainments. “No Sweeter Art”, by Tony Pi, is another story of Ao, the candy magician. Ao is engaged by the local magistrate to protect him against a suspected assassination attempt at a Riddle duel. The magistrate is an expert riddle maker. Pi nicely intertwines Ao's ability – to make candy creatures and inhabit them remotely – with a good look at the riddle contest, with dangerous encounters with the gods of the Chinese Zodiac, and with serious concerns about the morality of killing even bad people.

Locus, June 2016

In Beneath Ceaseless Skies I found ... “The Sweetest Skill”, by Tony Pi, his latest story of Ao, whose magic is entwined with “the sweetest skill”: candymaking. In this entry he is charged by Tiger to save the Pale Tigress, guardian of Chengdu, who has been attacked by the Ten Crows gang. Straightforward enough, if hardly easy – but then Dog and Pig get involved, with ramifications, no doubt, for future stories in what’s become a quite enjoyable series.

Locus, June 2017

I quite enjoyed stories in the two April issues of Beneath Ceaseless Skies. In April 27 we get the latest of Tony Pi’s ongoing and very entertaining series about Tangren Ao, a sugar shaper who uses the magic in his candy animals to help people, often at the behest of the animal spirits of the zodiac. In “That Lingering Sweetness” he encounters a pair of curses in a stolen box of tea intended for the Emperor that has somehow fetched up at a local teashop. He must negotiate with Monkey and Goat, who have set the conflicting curses, and at the same time try to find a way to clean up some of the messes resulting from his earlier adventure. Fun stuff.

Monday, September 9, 2019

Friday, September 6, 2019

Birthday Review: The Scar, by China Mieville

Birthday Review: The Scar, by China Mieville

Today is China Mieville's 47th birthday. In his honor, then, here's what I wrote way back when about his third novel, The Scar. I should add, perhaps, that two of his later novels are better still: Embassytown and The City and the City are brilliant -- truly two of the best works of fantastika of the 21st century.

The Scar is China Mieville's third novel. His second, Perdido Street Station, was a major success, garnering him a Hugo nomination as well as plenty of critical acclaim and, unless I miss by guess, healthy sales. This new novel is set in the same world as Perdido Street Station, Bas Lag, and as such fits loosely into that vague subgenre sometimes called "Science Fantasy". That novel was set in the huge, corrupt, city of New Crobuzon. This novel opens with mysterious doings in the ocean, and then we meet the noted linguist Bellis Coldwine, who is fleeing New Crobuzon to the colony city of Nova Esperancia. A tenuous linkage to the events of Perdido Street Station is provided by Bellis's reasons for leaving: she was a former lover of the hero of Perdido Street Station, and she fears being rounded up as a potential witness after the rather catastrophic happenings in that book.

The ship carrying Bellis Coldwine (as well as ocean biologist Johannes Tearfly and a group of Remade prisoners including a man named Tanner Sack) does not get very far, though, before it is overtaken by pirates from the mysterious floating city Armada. Bellis, Johannes, and the other passengers and prisoners are taken to Armada, where they are informed they will live the rest of their lives. They cannot leave the floating city, but they will otherwise be allowed full citizenship. Tanner Sack and Johannes accept fairly eagerly, but Bellis is desperate to have a chance to return to her beloved home city. Soon she falls into league with the mysterious Silas Fennec, a spy from New Crobuzon who is as desperate as she to return home, in his case because he has information of a coming attack on their city. It becomes clear that the leaders of Armada are engaged in a mysterious project, and Bellis becomes a key figure when she finds a crucial book in a language that she is a leading expert in. She learns that Armada is planning to harness a huge sea creature called an avanc, and to have the avanc tow the floating city to the dangerous rift in reality called the Scar, where it might be possible to do "Probability Mining". More importantly to her and Fennec, her new influence gives her the chance to get a message Fennec has prepared back to New Crobuzon.

The story takes further twists and turns from there -- it's very intelligently plotted, with the motivations of the characters well portrayed, and with plot elements that seem weak later revealed, after a twist or two, to make much more sense. But it's not the plot that is the key to enjoying the book. The characters are also fascinating. Besides Bellis and Tanner and Fennec, there are such Armadan figures as the Lovers, male and female leaders of Armada's strongest "riding", who scar each other symmetrically during their S&Mish lovemaking; Uther Doul, the dour and enigmatic bodyguard with a sword forged by the creatures who made the Scar, a sword that flickers through multiple possible outcomes, possible paths, at once; and the Brucolac, a vampir, and a fairly conventional one, but still strikingly portrayed.

As in Perdido Street Station, Mieville invents fascinating part-human species, hybrids of humans and other forms, in this book most strikingly the anophelii, mosquito men, and, more scarily and affectingly, mosquito women. In the end it is Mieville's fervent, sometimes overheated, imagination, that drives the book. His descriptions of cruel and dirty places, and odd creatures, are endless intriguing. Yes, he sometimes luxuriates overmuch in grotesquerie, but I suspect any application of discipline to his imagination would lose us more neat visions than we might gain by avoiding the occasional silliness or vulgarness. The book is also a bit too long -- some of this is the author's delight in showing us this or that cool gross notion he has had, but also I think his sense of pace is weak. A fair number of scenes, I think, could readily have been excised or shortened. (Such as most of the grindylow "interludes".) The other weakness is one fairly common in certain fantasy: when so many weird magical things are allowed, on occasion it seems that things happen, or characters gain powers, for reasons of the plot only. But though the book is a bit overlong, it remains compelling reading, and though the magical happenings aren't always fully consistent, they really don't strain suspension of disbelief too much: on the whole, this is another outstanding effort from Mieville. I'd rank it about even with Perdido Street Station, and perhaps slightly better on the grounds that the plot really is worked out quite well, with plenty of surprises and an honest, satisfying, resolution.

Today is China Mieville's 47th birthday. In his honor, then, here's what I wrote way back when about his third novel, The Scar. I should add, perhaps, that two of his later novels are better still: Embassytown and The City and the City are brilliant -- truly two of the best works of fantastika of the 21st century.

The Scar is China Mieville's third novel. His second, Perdido Street Station, was a major success, garnering him a Hugo nomination as well as plenty of critical acclaim and, unless I miss by guess, healthy sales. This new novel is set in the same world as Perdido Street Station, Bas Lag, and as such fits loosely into that vague subgenre sometimes called "Science Fantasy". That novel was set in the huge, corrupt, city of New Crobuzon. This novel opens with mysterious doings in the ocean, and then we meet the noted linguist Bellis Coldwine, who is fleeing New Crobuzon to the colony city of Nova Esperancia. A tenuous linkage to the events of Perdido Street Station is provided by Bellis's reasons for leaving: she was a former lover of the hero of Perdido Street Station, and she fears being rounded up as a potential witness after the rather catastrophic happenings in that book.

The ship carrying Bellis Coldwine (as well as ocean biologist Johannes Tearfly and a group of Remade prisoners including a man named Tanner Sack) does not get very far, though, before it is overtaken by pirates from the mysterious floating city Armada. Bellis, Johannes, and the other passengers and prisoners are taken to Armada, where they are informed they will live the rest of their lives. They cannot leave the floating city, but they will otherwise be allowed full citizenship. Tanner Sack and Johannes accept fairly eagerly, but Bellis is desperate to have a chance to return to her beloved home city. Soon she falls into league with the mysterious Silas Fennec, a spy from New Crobuzon who is as desperate as she to return home, in his case because he has information of a coming attack on their city. It becomes clear that the leaders of Armada are engaged in a mysterious project, and Bellis becomes a key figure when she finds a crucial book in a language that she is a leading expert in. She learns that Armada is planning to harness a huge sea creature called an avanc, and to have the avanc tow the floating city to the dangerous rift in reality called the Scar, where it might be possible to do "Probability Mining". More importantly to her and Fennec, her new influence gives her the chance to get a message Fennec has prepared back to New Crobuzon.

The story takes further twists and turns from there -- it's very intelligently plotted, with the motivations of the characters well portrayed, and with plot elements that seem weak later revealed, after a twist or two, to make much more sense. But it's not the plot that is the key to enjoying the book. The characters are also fascinating. Besides Bellis and Tanner and Fennec, there are such Armadan figures as the Lovers, male and female leaders of Armada's strongest "riding", who scar each other symmetrically during their S&Mish lovemaking; Uther Doul, the dour and enigmatic bodyguard with a sword forged by the creatures who made the Scar, a sword that flickers through multiple possible outcomes, possible paths, at once; and the Brucolac, a vampir, and a fairly conventional one, but still strikingly portrayed.

As in Perdido Street Station, Mieville invents fascinating part-human species, hybrids of humans and other forms, in this book most strikingly the anophelii, mosquito men, and, more scarily and affectingly, mosquito women. In the end it is Mieville's fervent, sometimes overheated, imagination, that drives the book. His descriptions of cruel and dirty places, and odd creatures, are endless intriguing. Yes, he sometimes luxuriates overmuch in grotesquerie, but I suspect any application of discipline to his imagination would lose us more neat visions than we might gain by avoiding the occasional silliness or vulgarness. The book is also a bit too long -- some of this is the author's delight in showing us this or that cool gross notion he has had, but also I think his sense of pace is weak. A fair number of scenes, I think, could readily have been excised or shortened. (Such as most of the grindylow "interludes".) The other weakness is one fairly common in certain fantasy: when so many weird magical things are allowed, on occasion it seems that things happen, or characters gain powers, for reasons of the plot only. But though the book is a bit overlong, it remains compelling reading, and though the magical happenings aren't always fully consistent, they really don't strain suspension of disbelief too much: on the whole, this is another outstanding effort from Mieville. I'd rank it about even with Perdido Street Station, and perhaps slightly better on the grounds that the plot really is worked out quite well, with plenty of surprises and an honest, satisfying, resolution.

Wednesday, September 4, 2019

Birthday Review: Stories of Rick Wilber

Today is Rick Wilber's 71st birthday. I've gotten to know Rick fairly well meeting him at numerous conventions over the past years -- he's a St. Louis native, and I live there, which makes one connection, and Rick is the son of a major league ballplayer (Del Wilber) and a baseball player and fan himself -- and I wasn't much of a ballplayer after hitting .600 or so in Little League (I was exposed once I saw a curveball), but I'm still a fan, so there's another connection. Rick's also a damn fine writer, and his story "Today is Today" will be in my 2019 Best of the Year book. His stories often feature baseball as a major element, and sometimes St. Louis as well (so that, for example, I'm pretty sure I know exactly what Kirkwood nursing home is mentioned in "Walking to Boston".) Here's a selection of my reviews of his more recent stories in Locus:

Locus, November 2010

Better still is Rick Wilber’s “Several Items of Interest” (Asimov's, October-November), the latest in a series of stories about the aftermath of the invasion of Earth by the S’hudonni. It concerns two brothers. Inevitably, one is a collaborator, who has been rewarded profoundly (with wealth, health, and sex) for telling the S’hudoni story as they – or as his patron, Twoclicks – want it told. The other is a resistance leader. That’s an old story, and Wilber doesn’t do anything fundamentally new with it, but the familiar ground is traveled very well. We see the brothers’ personal history, and why each chose his path, and we see the complications of S’hudoni politics, and the choices are not as straightforward as might be expected. As I say – nothing much here is really new, but it’s quite fun.

Locus, April 2012

Rick Wilber's novelette “Something Real” (Asimov's, April-May) takes on baseball player and spy Moe Berg, in a story set in multiple alternate worlds during World War II, in which he must wrestle with the notion of assassinating Werner Heisenberg, who may have been on the cusp of developing an atomic bomb for Germany. '

Locus, November 2015

Probably the best thing in the October-November Asimov's is Rick Wilber's “Walking to Boston”, set in WWII Ireland and in 1980s St. Louis, as Harry Mack visits his wife in a Kirkwood, MO, nursing home and indulges her desire to travel to Boston, where he'd promised to take her on their honeymoon. Niamh was an Irish girl whom he met when his bomber crashed on the way to England during the War, and we hear of the crash, and how Harry and Niamh met, and her grandmother and the “sisters”, and Harry's less than faithful treatment of her after their marriage. Most of us will guess who the “sisters” are easily enough, but they are mainly a vehicle for a story of character, and a nicely done story it is.

Locus, July 2018

Asimov’s for May/June opens and closes with entertaining novellas. Rick Wilber and Alan Smale offer “The Wandering Warriors”, about a semipro baseball team, just after World War II (in a slightly alternate history), who are then transported to ancient Rome, at the time of the interregnum between the Emperor Septimius Severus and his two sons, Caracalla and Geta. Luckily their catcher and leader, the Professor, knows Latin, and they are able to land on their feet, so to speak, ending up in the Colosseum for a baseball tournament in celebration of the two new Emperors. Of course, there is intrigue, involving the famously awful Caracalla and his rivalry with his somewhat nicer brother, and particularly their mother, Julia Domna, who turns out to be a good baseball player in her own right (though in our history she’d have been about 50 at the time). I have to say the Romans' ready adoption of baseball didn’t really convince me, but the story remains a good read.

Locus, September 2018

Rick Wilber’s “Today is Today” (Stonecoast Review, Summer) reflects on parallel universes as the narrator meditates on numerous alternate tracks his life might have taken, concerning his sports career, his relationship with his wife, and especially the life of his daughter, who in most of these tracks has Down Syndrome. (The early reference to the Billikens of Loyola University of St. Louis clued this St. Louis resident in right away to the fact that the prime universe displayed here is not our own!) Again – the story is in the end about a father and his daughter – and quite movingly so – the SFnal apparatus is an enabling element, but used quite effectively.

Locus, November 2010

Better still is Rick Wilber’s “Several Items of Interest” (Asimov's, October-November), the latest in a series of stories about the aftermath of the invasion of Earth by the S’hudonni. It concerns two brothers. Inevitably, one is a collaborator, who has been rewarded profoundly (with wealth, health, and sex) for telling the S’hudoni story as they – or as his patron, Twoclicks – want it told. The other is a resistance leader. That’s an old story, and Wilber doesn’t do anything fundamentally new with it, but the familiar ground is traveled very well. We see the brothers’ personal history, and why each chose his path, and we see the complications of S’hudoni politics, and the choices are not as straightforward as might be expected. As I say – nothing much here is really new, but it’s quite fun.

Locus, April 2012

Rick Wilber's novelette “Something Real” (Asimov's, April-May) takes on baseball player and spy Moe Berg, in a story set in multiple alternate worlds during World War II, in which he must wrestle with the notion of assassinating Werner Heisenberg, who may have been on the cusp of developing an atomic bomb for Germany. '

Locus, November 2015

Probably the best thing in the October-November Asimov's is Rick Wilber's “Walking to Boston”, set in WWII Ireland and in 1980s St. Louis, as Harry Mack visits his wife in a Kirkwood, MO, nursing home and indulges her desire to travel to Boston, where he'd promised to take her on their honeymoon. Niamh was an Irish girl whom he met when his bomber crashed on the way to England during the War, and we hear of the crash, and how Harry and Niamh met, and her grandmother and the “sisters”, and Harry's less than faithful treatment of her after their marriage. Most of us will guess who the “sisters” are easily enough, but they are mainly a vehicle for a story of character, and a nicely done story it is.

Locus, July 2018

Asimov’s for May/June opens and closes with entertaining novellas. Rick Wilber and Alan Smale offer “The Wandering Warriors”, about a semipro baseball team, just after World War II (in a slightly alternate history), who are then transported to ancient Rome, at the time of the interregnum between the Emperor Septimius Severus and his two sons, Caracalla and Geta. Luckily their catcher and leader, the Professor, knows Latin, and they are able to land on their feet, so to speak, ending up in the Colosseum for a baseball tournament in celebration of the two new Emperors. Of course, there is intrigue, involving the famously awful Caracalla and his rivalry with his somewhat nicer brother, and particularly their mother, Julia Domna, who turns out to be a good baseball player in her own right (though in our history she’d have been about 50 at the time). I have to say the Romans' ready adoption of baseball didn’t really convince me, but the story remains a good read.

Locus, September 2018

Rick Wilber’s “Today is Today” (Stonecoast Review, Summer) reflects on parallel universes as the narrator meditates on numerous alternate tracks his life might have taken, concerning his sports career, his relationship with his wife, and especially the life of his daughter, who in most of these tracks has Down Syndrome. (The early reference to the Billikens of Loyola University of St. Louis clued this St. Louis resident in right away to the fact that the prime universe displayed here is not our own!) Again – the story is in the end about a father and his daughter – and quite movingly so – the SFnal apparatus is an enabling element, but used quite effectively.

Sunday, September 1, 2019

Birthday Review: Dragon and Thief, by Timothy Zahn

Today is Timothy Zahn's 68th birthday. He's perhaps best known for his Star Wars novels, but he's done a lot of pretty enjoyable SF on his own. And he's a fellow U of I grad -- a few years (8, I suppose!) before me. Here's what I wrote about the first book in a YA series that I read with enjoyment until the end.

Dragon and Thief, by Timothy Zahn

Timothy Zahn is probably best-known for his Star Wars novelizations, which seem to be fairly well-regarded among media tie-in books, and SW novelizations in particular. I haven't read them myself. He first appeared in the field with stories in Analog, one of which ("Cascade Point") won a Hugo, and with some military SF novels. I've found his writing (I've only read short fiction) fairly enjoyable -- he usually tells a decent story. I believe he has said that he has made enough money from the SW books to write what he wants nowadays.

His new book [as of 2003], advertised as the first of a series, is Dragon and Thief. This is basically a Young Adult novel. I enjoyed it quite a lot -- it is quite satisfying not too ambitious space adventure. It is, to use that most cliche of terms, a good read. There are a few nice ideas incorporated into a fairly routine plot, with a story resolved acceptably in this book, as well as the beginning of a story arc that will probably be quite sufficient for a series.

There are two main characters, announced by the title. The Dragon is an alien called Draycos (the implausible dragon-like given name (possibly handwaved away in the text but so what) is one of a few lazy things about the world-building), a "warrior-poet" of a race of symbiotic beings. These folks and their host species are fleeing a genocidally evil alien race from another arm of the Galaxy, in hopes of colonizing a likely world in our arm. The advance team, including Draycos and his host, arrives only to find that they have been betrayed -- the bad guys are waiting and kill everyone except Draycos. And Draycos, like all his species, can only survive about six hours without a host.

The Thief is Jack Morgan, a teenaged boy who has been working criminally with his Uncle Virge for some time. He wants to go straight, and be a cargo-hauler with his Uncle's ship, but already they have been framed and accused of stealing some valuable cargo. They flee to an empty world -- which not surprisingly is the world where Draycos's people ended up. And it turns out that humans, such as Jack, are an acceptable host for the dragons -- so when Jack investigates Draycos's crashed ship, he finds himself with an unwanted guest.

The neat characteristic of Draycos's people is that they can occupy other dimensions, staying in contact with our 3-d space in 2-d form, as a sort of tattoo on their host. I thought that a really cute idea, and well-handled in the book. There is another secret about Jack that Zahn hides well for a while, which I won't reveal -- partly because I guessed it myself and had fun guessing it. At any rate Draycos agrees to help Jack figure out who framed he and his Uncle, and maybe solve that problem -- but in return he wants to stay with Jack as a host for as long as possible, and he hopes Jack will help him discover who betrayed them, and find a means of countering the threat of the genocidal aliens.

The story is fast-moving and fun and at least believable enough for this sort of book, and the main characters are enjoyable to be with. The book points a moral, mainly about Jack needing to learn that cooperation with another person for a larger goal than self-advancement is a good thing -- and it does so pretty naturally and without too much preaching. I liked it as very nice light reading -- I'll read the next book in the series for sure and probably the whole thing -- and I would think it an excellent book to recommend to early teenaged readers looking for good YA SF in pretty much the Heinlein Juvenile mode.

Dragon and Thief, by Timothy Zahn

Timothy Zahn is probably best-known for his Star Wars novelizations, which seem to be fairly well-regarded among media tie-in books, and SW novelizations in particular. I haven't read them myself. He first appeared in the field with stories in Analog, one of which ("Cascade Point") won a Hugo, and with some military SF novels. I've found his writing (I've only read short fiction) fairly enjoyable -- he usually tells a decent story. I believe he has said that he has made enough money from the SW books to write what he wants nowadays.

His new book [as of 2003], advertised as the first of a series, is Dragon and Thief. This is basically a Young Adult novel. I enjoyed it quite a lot -- it is quite satisfying not too ambitious space adventure. It is, to use that most cliche of terms, a good read. There are a few nice ideas incorporated into a fairly routine plot, with a story resolved acceptably in this book, as well as the beginning of a story arc that will probably be quite sufficient for a series.

There are two main characters, announced by the title. The Dragon is an alien called Draycos (the implausible dragon-like given name (possibly handwaved away in the text but so what) is one of a few lazy things about the world-building), a "warrior-poet" of a race of symbiotic beings. These folks and their host species are fleeing a genocidally evil alien race from another arm of the Galaxy, in hopes of colonizing a likely world in our arm. The advance team, including Draycos and his host, arrives only to find that they have been betrayed -- the bad guys are waiting and kill everyone except Draycos. And Draycos, like all his species, can only survive about six hours without a host.

The Thief is Jack Morgan, a teenaged boy who has been working criminally with his Uncle Virge for some time. He wants to go straight, and be a cargo-hauler with his Uncle's ship, but already they have been framed and accused of stealing some valuable cargo. They flee to an empty world -- which not surprisingly is the world where Draycos's people ended up. And it turns out that humans, such as Jack, are an acceptable host for the dragons -- so when Jack investigates Draycos's crashed ship, he finds himself with an unwanted guest.

The neat characteristic of Draycos's people is that they can occupy other dimensions, staying in contact with our 3-d space in 2-d form, as a sort of tattoo on their host. I thought that a really cute idea, and well-handled in the book. There is another secret about Jack that Zahn hides well for a while, which I won't reveal -- partly because I guessed it myself and had fun guessing it. At any rate Draycos agrees to help Jack figure out who framed he and his Uncle, and maybe solve that problem -- but in return he wants to stay with Jack as a host for as long as possible, and he hopes Jack will help him discover who betrayed them, and find a means of countering the threat of the genocidal aliens.

The story is fast-moving and fun and at least believable enough for this sort of book, and the main characters are enjoyable to be with. The book points a moral, mainly about Jack needing to learn that cooperation with another person for a larger goal than self-advancement is a good thing -- and it does so pretty naturally and without too much preaching. I liked it as very nice light reading -- I'll read the next book in the series for sure and probably the whole thing -- and I would think it an excellent book to recommend to early teenaged readers looking for good YA SF in pretty much the Heinlein Juvenile mode.

Saturday, August 31, 2019

Birthday Review: Sleeping Planet, by William R. Burkett, Jr.

Birthday Review: Sleeping Planet, by William R. Burkett, Jr.

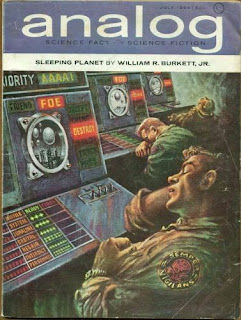

William R. Burkett, Jr., turns 76 today. He isn't much remembered in SF this days, but his first novel, an Analog serial from the bedsheet days, is still remembered fondly in some circles. He was a journalist by main profession. He published two more SF books much later in 1998, Bloodsport and Blood Lines, books that the Science Fiction Encyclopedia describes as spoofish Space Opera about a big game hunter and his cyborg sidekick. In 2013, he self-published A Matter of Logistics 1, an expansion of a novella that John W. Campbell had rejected in 1968. (Campbell apparently had told him it needed to be expanded, and either Burkett didn't have time to do it then, or perhaps by the time he could take it further Campbell had died.) The second part of A Matter of Logistics hasn't appeared yet. Here's what I wrote about Sleeping Planet some while back:

One of the novels I used to hear cited every so often, in places like rec.arts.sf-written, as an underappreciated old SF book, is William R. Burkett, Jr.'s Sleeping Planet. I've seen it cited by a couple of people as an all-time favorite, and it often comes up in lists of "humorous SF". It comes up particularly often, and most appropriately, when people as for "writers like Eric Frank Russell". That last, at least, is true. Sleeping Planet reads almost like an EFR pastiche. It was serialized in Analog in the July through September 1964 issues, at about the time Russell retired. While John Campbell's main Russell replacement, in my view, was Christopher Anvil, he was always a sucker for stories of this type.

And what type is that? "Stupid Alien" stories. The sort of thing Russell did in Next of Kin, Wasp, Three to Conquer, "Nuisance Value", and other stories, and the sort of thing Anvil did in his Pandora stories. (Though to give Anvil his due, his "stupid aliens" weren't entirely cliche stupid aliens -- in some ways they really were superior to humans, and in fact they end up winning, though partly by letting the humans "join" them.) The basic idea is to either a) have aliens with what should be superior tech or numbers invade Earth, and be repulsed by human pluck or ingenuity; or b) have a few humans (or just one) be stuck on the alien planet and single-handedly outwit an entire planet of aliens. Sleeping Planet fits template a.

The story is told from three main viewpoints. James Rierson is a lawyer who is hunting in backwoods Georgia when strange things start to happen, beginning with the deer he is after just collapsing to sleep. Bradford Donovan is an ex-soldier, invalided due to his two artificial legs, who finds himself the only person who stays awake in an air-raid shelter after the alien Llarans attack. Martak Sarno is the Supreme Commander of the Llaran invasion fleet. It is Sarno who discovered the Llaran secret weapon, which he hopes will turn the tide in a decades long war. A plant on one of the Llaran colony planets secretes a poison which is harmless to Llarans but which puts Terran life to sleep, normally for just hours but Sarno's project has extended this period to months. The catch is that once exposed to this plant and put to sleep once, Terrans are immune to its effects. This means that a few humans who happen to have visited the Llaran planet in question and who encountered this plant are immune. Obviously, Rierson and Donovan are among those few.

Donovan is soon captured. But he soon gathers that Llarans are extremely superstitious, and he begins telling ghost stories and causing a loss of morale among the rank and file invaders. (This is a particularly Russell-like notion.) All this would come to nothing except that Rierson, who spends some time sniping at isolated Llaran units, overhears some of the soldiers repeating Donovan's stories, and cooperates by planting the idea that he is one of the ghosts Donovan mentions. Even that wouldn't have helped, except that Rierson eventually discovers the one group of fairly intelligent Earth inhabitants that are unaffected by the gas: robots. The story, then, involves the coordinated efforts of Rierson, Donovan, and the robots to continue to spread fear among the Llarans, finally bringing them to surrender.

I suppose it's a pleasant enough story, but it hardly seems worth special remembrance. It's second-rate imitation Russell, basically. It's not really even very funny -- which to be fair wasn't really Burkett's intention, in my view. Certainly the occasional atrocities committed by the aliens are hard to laugh at. It depends too much on implausibilities -- I suppose the first one, the unlikely effects of the "sleeping gas", are acceptable as the raison d'etre for the story, but the way the action plays out, and especially the convenient dullness of the aliens, just didn't convince me. Finally, there just wasn't enough cleverness. All the above shortcomings could have been overcome simply by a sufficient quantity of clever or silly or just plain adventurous happenings, but there really isn't enough here. A very minor work.

William R. Burkett, Jr., turns 76 today. He isn't much remembered in SF this days, but his first novel, an Analog serial from the bedsheet days, is still remembered fondly in some circles. He was a journalist by main profession. He published two more SF books much later in 1998, Bloodsport and Blood Lines, books that the Science Fiction Encyclopedia describes as spoofish Space Opera about a big game hunter and his cyborg sidekick. In 2013, he self-published A Matter of Logistics 1, an expansion of a novella that John W. Campbell had rejected in 1968. (Campbell apparently had told him it needed to be expanded, and either Burkett didn't have time to do it then, or perhaps by the time he could take it further Campbell had died.) The second part of A Matter of Logistics hasn't appeared yet. Here's what I wrote about Sleeping Planet some while back:

|

| (Cover by Kelly Freas) |

And what type is that? "Stupid Alien" stories. The sort of thing Russell did in Next of Kin, Wasp, Three to Conquer, "Nuisance Value", and other stories, and the sort of thing Anvil did in his Pandora stories. (Though to give Anvil his due, his "stupid aliens" weren't entirely cliche stupid aliens -- in some ways they really were superior to humans, and in fact they end up winning, though partly by letting the humans "join" them.) The basic idea is to either a) have aliens with what should be superior tech or numbers invade Earth, and be repulsed by human pluck or ingenuity; or b) have a few humans (or just one) be stuck on the alien planet and single-handedly outwit an entire planet of aliens. Sleeping Planet fits template a.

The story is told from three main viewpoints. James Rierson is a lawyer who is hunting in backwoods Georgia when strange things start to happen, beginning with the deer he is after just collapsing to sleep. Bradford Donovan is an ex-soldier, invalided due to his two artificial legs, who finds himself the only person who stays awake in an air-raid shelter after the alien Llarans attack. Martak Sarno is the Supreme Commander of the Llaran invasion fleet. It is Sarno who discovered the Llaran secret weapon, which he hopes will turn the tide in a decades long war. A plant on one of the Llaran colony planets secretes a poison which is harmless to Llarans but which puts Terran life to sleep, normally for just hours but Sarno's project has extended this period to months. The catch is that once exposed to this plant and put to sleep once, Terrans are immune to its effects. This means that a few humans who happen to have visited the Llaran planet in question and who encountered this plant are immune. Obviously, Rierson and Donovan are among those few.

Donovan is soon captured. But he soon gathers that Llarans are extremely superstitious, and he begins telling ghost stories and causing a loss of morale among the rank and file invaders. (This is a particularly Russell-like notion.) All this would come to nothing except that Rierson, who spends some time sniping at isolated Llaran units, overhears some of the soldiers repeating Donovan's stories, and cooperates by planting the idea that he is one of the ghosts Donovan mentions. Even that wouldn't have helped, except that Rierson eventually discovers the one group of fairly intelligent Earth inhabitants that are unaffected by the gas: robots. The story, then, involves the coordinated efforts of Rierson, Donovan, and the robots to continue to spread fear among the Llarans, finally bringing them to surrender.

I suppose it's a pleasant enough story, but it hardly seems worth special remembrance. It's second-rate imitation Russell, basically. It's not really even very funny -- which to be fair wasn't really Burkett's intention, in my view. Certainly the occasional atrocities committed by the aliens are hard to laugh at. It depends too much on implausibilities -- I suppose the first one, the unlikely effects of the "sleeping gas", are acceptable as the raison d'etre for the story, but the way the action plays out, and especially the convenient dullness of the aliens, just didn't convince me. Finally, there just wasn't enough cleverness. All the above shortcomings could have been overcome simply by a sufficient quantity of clever or silly or just plain adventurous happenings, but there really isn't enough here. A very minor work.

Wednesday, August 28, 2019

Birthday Review: Stories of Chris Willrich

Birthday Review: Stories of Chris Willrich

Chris Willrich turns 52 today. He's a neat writer of both fantasy and SF, probably better known for his Persimmon and Bone fantasies (several short stories and three novels), but his SF has been very nice too. Here's a collection of my Locus reviews of his work:

Locus, July 2002

I also liked Chris Willrich's atmospheric fantasy "King Rainjoy's Tears" (F&SF, July), in which the poet Persimmon Gaunt and her lover, the thief Imago Bone, must find the exiled, personified, title objects, lest the compassion-deprived King force his country into war.

Locus, May 2003

Chris Willrich's "Count to One" (Asimov's, May) quite intriguingly considers the relationship of an AI and a human. Kwatee was developed to understand the Earth's climate well enough to recommend a course of action to save Earth from either runaway greenhouse effect or a new ice age. He "lives" mostly in a simulation of Earth, taking on a persona resembling an American Indian god. Now he faces danger from "wolves", viruses of some sort that have been attacking him. But he is also in love, with a woman who enters his simulation virtually. And he needs to make a decision -- what ecological changes are best? And best for whom? Humans? Earth? Life in general? Kwatee? A very thoughtful, moving, piece.

Locus, August 2006

I thought the August issue of F&SF particularly strong, one of the best issues of any magazine this year. It opens and closes with strong novelettes. Chris Willrich’s “Penultima Thule” is another Persimmon Gaunt/Imago Bone story. The poet Gaunt and her lover Bone have headed north, hoping to dispose of the deadly book they have stolen, a “cacography”. Reading it is fatal, and its influence is malignant even unread. But nearly at the northern rim of the world Bone is captured by the Stonekin, to become a victim of the “Hunger Stone”. Gaunt must free him and then flee with him to the Rim – still not knowing what will result of ridding the world of the book. It’s colorful, dourly romantic, and bleakly funny, and in the end moving and poetic.

Locus, September 2007

The pick story in the August F&SF is Chris Willrich’s “A Wizard of the Old School”. This is another story about the thieves Persimmon Gaunt and Imago Bone. But here the title character is central: Krumwheezle of the Old School. It was he who identified the baleful book which featured in the previous story “Penultima Thule”. In this story we learn more of Krumwheezle – his history at the Old School, his lost lover, his quiet life in his adopted village. And when Gaunt and Bone return, still cursed though they hope to have a child, he joins them on a quest that may cure them – and, it turns out, may cure some of his own problems, problems he hardly acknowledges. This is a story that is both a satisfying and imaginative high fantasy, and an equally satisfying, slightly sentimental, domestic tale.

Locus, January 2009

The new webzine Beneath Ceaseless Skies, devoted to, in editor Scott H. Andrews’s words, “literary adventure fantasy”, is off to a promising start. The first couple of issues of this biweekly magazine feature a strong Gaunt and Bone story from Chris Willrich, in which his continuing characters, a pair of lovers, one a thief, one a poet, are charged with returning the title object, “The Sword of Loving Kindness”, to its rightful owner – with consequences expected to be dire, yet which turn out ironically different.

Locus, June 2009

Another very pure SF story in the June Asimov's comes from Chris Willrich, better known for his sword and sorcery stories at F&SF. “Sails the Morne” is a very strange story, only slowly comprehensible – but in a good way. It evolves into a mystery, with a spaceship and its motley crew (humans and AIs, from Earth and elsewhere) transporting a valuable artifact (The Book of Kells) as well as a likewise motley group of aliens to an Exposition on the outskirts of the Solar system. Theft and murder result … it’s very entertaining, often quite funny, satisfyingly concluded.

Locus, September 2011

The new Black Gate is another monster-sized issue. (Full disclosure – I have an article in the magazine, and am a regular contributor.) As ever it’s stuffed with satisfying adventure fantasy. Notable here is how often the heroes are the unexpected: for example Chris Willrich’s “The Lions of Karthagar”, in which two armies from opposite sides of the world converge on the peaceful city of Karthagar, beside the Ruby Waste, there to learn that peace comes at a price. Conventional enough, if well executed, except that the story is told through two aging weatherworkers, one from each camp, who find in each other something more valuable than their ambitious masters, or the utopia of Karthagar.

Locus, May-June 2012

Finally, in the May F&SF, Chris Willrich offers “Grand Tour”, in which I-Chen Fisher is a young woman, ready to take her “Grand Tour” among the stars, while her loving but perhaps a little stifling family readies to see her off, and to leave on a Wanderjahr of their own. Luckily, she meets a boy her own age with his different sort of family problems. Little enough really happens, but it's a nice glimpse of an expansive-seeming future, and a nice look at a few well-drawn characters.

Chris Willrich has another story, “The Mote Dancer and the Firelife”, at Beneath Ceaseless Skies for March 8. Oddly enough, its main character is also named I-Chen – perhaps she is meant to be a much older version of the character in “Grand Tour”? (Not that the story suggests that!) She's returned to the planet where her husband died, accompanied by his ghost, to look for resolution of sorts. The natives of this planet, called Spinies, can link into a network facilitated by ancient alien technology (“Motes”), and they feel a certain contempt for humans, who mostly can't. But I-Chen is a rare human “Mote Dancer” … The story involves the alien's habit of fighting as pairs (“Quixotes” and “Sanchos”), and the “Firelife” where their dead go – including perhaps the Spiny who killed her husband. It's neat, colorful stuff.

Chris Willrich turns 52 today. He's a neat writer of both fantasy and SF, probably better known for his Persimmon and Bone fantasies (several short stories and three novels), but his SF has been very nice too. Here's a collection of my Locus reviews of his work:

Locus, July 2002

I also liked Chris Willrich's atmospheric fantasy "King Rainjoy's Tears" (F&SF, July), in which the poet Persimmon Gaunt and her lover, the thief Imago Bone, must find the exiled, personified, title objects, lest the compassion-deprived King force his country into war.

Locus, May 2003

Chris Willrich's "Count to One" (Asimov's, May) quite intriguingly considers the relationship of an AI and a human. Kwatee was developed to understand the Earth's climate well enough to recommend a course of action to save Earth from either runaway greenhouse effect or a new ice age. He "lives" mostly in a simulation of Earth, taking on a persona resembling an American Indian god. Now he faces danger from "wolves", viruses of some sort that have been attacking him. But he is also in love, with a woman who enters his simulation virtually. And he needs to make a decision -- what ecological changes are best? And best for whom? Humans? Earth? Life in general? Kwatee? A very thoughtful, moving, piece.

Locus, August 2006

I thought the August issue of F&SF particularly strong, one of the best issues of any magazine this year. It opens and closes with strong novelettes. Chris Willrich’s “Penultima Thule” is another Persimmon Gaunt/Imago Bone story. The poet Gaunt and her lover Bone have headed north, hoping to dispose of the deadly book they have stolen, a “cacography”. Reading it is fatal, and its influence is malignant even unread. But nearly at the northern rim of the world Bone is captured by the Stonekin, to become a victim of the “Hunger Stone”. Gaunt must free him and then flee with him to the Rim – still not knowing what will result of ridding the world of the book. It’s colorful, dourly romantic, and bleakly funny, and in the end moving and poetic.

Locus, September 2007

The pick story in the August F&SF is Chris Willrich’s “A Wizard of the Old School”. This is another story about the thieves Persimmon Gaunt and Imago Bone. But here the title character is central: Krumwheezle of the Old School. It was he who identified the baleful book which featured in the previous story “Penultima Thule”. In this story we learn more of Krumwheezle – his history at the Old School, his lost lover, his quiet life in his adopted village. And when Gaunt and Bone return, still cursed though they hope to have a child, he joins them on a quest that may cure them – and, it turns out, may cure some of his own problems, problems he hardly acknowledges. This is a story that is both a satisfying and imaginative high fantasy, and an equally satisfying, slightly sentimental, domestic tale.

Locus, January 2009

The new webzine Beneath Ceaseless Skies, devoted to, in editor Scott H. Andrews’s words, “literary adventure fantasy”, is off to a promising start. The first couple of issues of this biweekly magazine feature a strong Gaunt and Bone story from Chris Willrich, in which his continuing characters, a pair of lovers, one a thief, one a poet, are charged with returning the title object, “The Sword of Loving Kindness”, to its rightful owner – with consequences expected to be dire, yet which turn out ironically different.

Locus, June 2009

Another very pure SF story in the June Asimov's comes from Chris Willrich, better known for his sword and sorcery stories at F&SF. “Sails the Morne” is a very strange story, only slowly comprehensible – but in a good way. It evolves into a mystery, with a spaceship and its motley crew (humans and AIs, from Earth and elsewhere) transporting a valuable artifact (The Book of Kells) as well as a likewise motley group of aliens to an Exposition on the outskirts of the Solar system. Theft and murder result … it’s very entertaining, often quite funny, satisfyingly concluded.

Locus, September 2011

The new Black Gate is another monster-sized issue. (Full disclosure – I have an article in the magazine, and am a regular contributor.) As ever it’s stuffed with satisfying adventure fantasy. Notable here is how often the heroes are the unexpected: for example Chris Willrich’s “The Lions of Karthagar”, in which two armies from opposite sides of the world converge on the peaceful city of Karthagar, beside the Ruby Waste, there to learn that peace comes at a price. Conventional enough, if well executed, except that the story is told through two aging weatherworkers, one from each camp, who find in each other something more valuable than their ambitious masters, or the utopia of Karthagar.

Locus, May-June 2012

Finally, in the May F&SF, Chris Willrich offers “Grand Tour”, in which I-Chen Fisher is a young woman, ready to take her “Grand Tour” among the stars, while her loving but perhaps a little stifling family readies to see her off, and to leave on a Wanderjahr of their own. Luckily, she meets a boy her own age with his different sort of family problems. Little enough really happens, but it's a nice glimpse of an expansive-seeming future, and a nice look at a few well-drawn characters.

Chris Willrich has another story, “The Mote Dancer and the Firelife”, at Beneath Ceaseless Skies for March 8. Oddly enough, its main character is also named I-Chen – perhaps she is meant to be a much older version of the character in “Grand Tour”? (Not that the story suggests that!) She's returned to the planet where her husband died, accompanied by his ghost, to look for resolution of sorts. The natives of this planet, called Spinies, can link into a network facilitated by ancient alien technology (“Motes”), and they feel a certain contempt for humans, who mostly can't. But I-Chen is a rare human “Mote Dancer” … The story involves the alien's habit of fighting as pairs (“Quixotes” and “Sanchos”), and the “Firelife” where their dead go – including perhaps the Spiny who killed her husband. It's neat, colorful stuff.

Birthday Review: The Narrow Land, by Jack Vance

The Narrow Land, by Jack Vance

a review by Rich Horton

The Narrow Land is an interesting collection by Jack Vance. It dates to about 1980, though first publication seems to be 1982 in a DAW edition. That is to say, it's copyright 1980, and the internal matter (with which Contento and the ISFDB agree) says that the first publication was in 1982 by DAW. The edition I have is a 1984 Coronet (UK) paperback. The stories, however, date to much earlier: one from 1967, one from 1963, and the others to 1956 and earlier still. So it's a bit odd: almost a collection of odds and ends and leftovers, you would think. But actually it has some very good stuff, and some quite significant stuff.

Perhaps most interesting is Vance's very first published story, "The World-Thinker", from the Summer 1945 Thrilling Wonder Stories. This is a striking story, quite Vancean (much more so than lots of early Vance, such as the weaker Magnus Ridolph stories), certainly rather clumsy in some ways but still effective. More to the point, perhaps, it really shows certain of Vance's career long characteristics, particularly the odd (or perhaps not so odd) mix of hints of misogynism with the depiction of the major female character as strong and independent.

One of the '60s stories is the title piece, about the coming of age of an alien in a strange environment. (The environment, I believe, is intended to be the terminator of a tide-locked planet: hence "The Narrow Land", though that is never made explicit.) The alien, a creature called Ern, grows up among similar beings, who nonetheless are different from him -- eventually he learns the truth about his nature (which is tied up interestingly with the species' life cycle). The other later story is "Green Magic", in my opinion one of Vance's best short fantasies, about a man who after much effort learns the secret of entry to the "green" plane of magic.

The other stories include are "The Ten Books", "Chateau D'If", "Where Hesperus Falls", and "The Masquerade on Dicantropus". The latter two are very minor. "Chateau D'If" is a decent long novella, published under a different (and silly, as it is a spoiler, so I won't mention it) title in Thrilling Wonder in 1950. It's about five men who decide to answer an ad for the title business, which promises mysterious adventure -- but something more sinister is up. Not by any means great, but fun and scary. And "The Ten Books" (aka "Men of the Ten Books") is a rather Campbellian story (though it actually sold to Startling Stories) about the rediscovery of a lost Earth colony, which seems to be an Utopia, but the people of which revere the memory of Earth, and believe that Earth must be much superior to their society. (This story made one of the Bleiler/Dikty Year's Best volumes.)

All in all, quite a good story collection, and I find it odd that stories as good (though not great) as these were uncollected by 1980.

a review by Rich Horton

|

| (Cover by Wayne Barlowe) |

Perhaps most interesting is Vance's very first published story, "The World-Thinker", from the Summer 1945 Thrilling Wonder Stories. This is a striking story, quite Vancean (much more so than lots of early Vance, such as the weaker Magnus Ridolph stories), certainly rather clumsy in some ways but still effective. More to the point, perhaps, it really shows certain of Vance's career long characteristics, particularly the odd (or perhaps not so odd) mix of hints of misogynism with the depiction of the major female character as strong and independent.

One of the '60s stories is the title piece, about the coming of age of an alien in a strange environment. (The environment, I believe, is intended to be the terminator of a tide-locked planet: hence "The Narrow Land", though that is never made explicit.) The alien, a creature called Ern, grows up among similar beings, who nonetheless are different from him -- eventually he learns the truth about his nature (which is tied up interestingly with the species' life cycle). The other later story is "Green Magic", in my opinion one of Vance's best short fantasies, about a man who after much effort learns the secret of entry to the "green" plane of magic.

|

| (Cover by George Underwood) |

All in all, quite a good story collection, and I find it odd that stories as good (though not great) as these were uncollected by 1980.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)