by Rich Horton

Leonard Knapp was born on June 2, 1915, though by the time he began publishing science fiction stories in 1938 he was using the name Lester del Rey, and continued to do so until his death in 1993. He told people various versions of his "true" name, typically a variation on "Ramon Felipe Alvarez-del Rey", and only after his estate was settled was it definitively settled that his birth name was Knapp. Throughout his career he used other pseudonyms as well, most notably Erik Van Lihn and Philip St. John. He made an early mark as a writer with stories like "Helen O'Loy" and "Nerves", each of which appeared in one of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies, but in later years he was often blocked. However, he had a major impact as an editor, at magazines like Space Science Fiction, and more notably at Ballantine Books, which SF/Fantasy imprint was renamed "Del Rey Books" after he and his wife Judy-Lynn. Lester Del Rey's most famous discovery was Terry Brooks -- he acquired and edited The Sword of Shannara and it became a smash bestseller. On the occasion of what would have been his 104th birthday, here's a look at his only Ace Double.

As I've noted before, many of the SFWA Grand Masters published in Ace Doubles. One of my goals is to review Ace Doubles by each of the Grand Masters who did have an Ace Double. Lester Del Rey is one of the interesting cases. His only Ace Double was one of the last. This book appeared in 1973, as the series was limping to a conclusion. Interestingly, this same pairing appeared earlier as a double book from a different publisher, one of the more unusual "double" series ever. This was the Galaxy Magabooks, put out by Galaxy magazine between 1963 and 1965. These "books" were in the format of issues of Galaxy, and they paired two short novels by the same author back to back (not dos-a-dos). The Sky Is Falling/Badge of Infamy was the first such book. The other two were Theodore Sturgeon's "... And My Fear is Great ..." paired with "Baby is Three" (two very short novels indeed, really indisputably novellas), and Jack Williamson's After World's End paired with The Legion of Time. (You can't fault the choice of authors -- two Grand Masters and the third author, Sturgeon, clearly the best of the three, not a Grand Master due only to a relatively early death.)

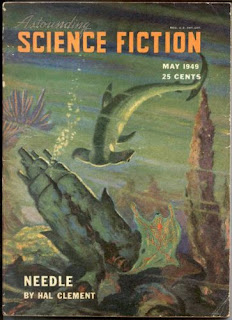

|

| (Cover by Virgil Finlay(?)) |

This caused me to wonder about stories that first appeared as collaborations, but were expanded to novels under only one name. Three other examples come immediately to mind: James Blish and Damon Knight's story "The Weakness of RVOG" became Blish's novel VOR, Poul Anderson and F. N. Waldrop's novelette "Tomorrow's Children" (Anderson's first published story, and Waldrop's only story -- and I wonder how much he really contributed) became Anderson's novel Twilight World, and Samuel R. Delany and James Sallis's novelette "They Fly at Çiron" became Delany's novel They Fly at Çiron. Anyone have any further examples?

[I wrote this in 2004 or so -- while I stand by my critical evaluations below I've softened on my disputes with the Grand Master decision in this and other cases, partly because SFWA has gone to one per year instead of a maximum of six per decade.] I am on record as not approving of the decision to make Lester Del Rey a Grand Master. I think a tenuous case can be made based on his editorial influence. He was editor of several minor magazines in the 50s, under various names (and he used to publish his own work under pseudonyms, so that as "Philip St. John" he edited SF Adventures and published "Lester Del Rey", and as Lester Del Rey he edited Space and published "St. John". Much more importantly, he was very influential in the 70s and 80s as an editor for Ballantine, and the Ballantine imprint Del Rey was named jointly after he and his wife Judy Lynn. In particular, Lester Del Rey discovered Terry Brooks's The Sword of Shannara, edited it rigorously, and made it a bestseller. In so doing he was crucial to popularizing the Tolkien-influenced subgenre we now call EFP, for "extruded fantasy product". So much for Del Rey the editor -- but my main interest is always in the writer. As a writer he was responsible for two stories in the SF Hall of Fame -- one a very good novella about a nuclear accident, "Nerves"; the other a forgettable and schmaltzy story about a robot "wife", "Helen O'Loy". Besides those stories there were a few more decent efforts ("For I am a Jealous People", "The Day is Done", "To Avenge Man", not much else); and several novels, many of which showed a quirky imagination and a desire to explore unpopular ideas, but none of which are really memorable. He really didn't publish all that much considering the length of his career. To my mind, it simply doesn't add up to a Grand Master's quality of work, nor even quantity.

Still, Del Rey was a pro. And he was a decent writer, and a writer who generally made an effort to have something to say. So both the stories in this Ace Double are readable, and they have some intriguing aspects. But neither is particularly special.

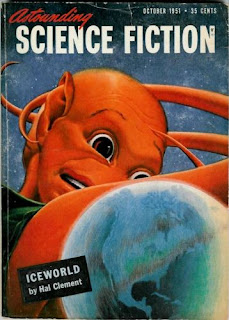

|

| (Cover by Alex Schomburg) |

The dead man in the flophouse turns out to have a certificate as a spaceship worker, and Feldman leaps at the chance to assume the other's identity and take a job on a ship heading for Mars. He is found out and expelled on Mars. There he learns that the maximally evil Earth guilds are squeezing the Martians (i.e. human colonists, -- the old Martians are long dead), and those Martians in the rebellious villages in particular. There is only one hospital on Mars, and so treatment is very hard to come by. Feldman becomes a secret doctor. He faces death if he is discovered, and his problem is exacerbated by the fact that his wife has come to Mars to set up a second hospital.

He discovers a long-incubating Martian plague, that likely has already spread to Earth. Unless a cure can be found, the populations of both planets will be decimated. But when he tries to alert authorities to this danger, he is arrested for performing illegal research. He is sentenced to die.

Well -- what do you think? Will he really die? Will his psychotic wife realize that her support of the psychotic rules about medical research is stupid? Will she have to get the plague first to realize her mistake? Will the Martians rebel? C'mon -- we all know the answers! The basic problem with the story is that the bad guys are so absurdly evull that there is no believing in them. As 50s SF adventure it works OK -- it's quite competently done, reads swiftly, holds the interest, but it doesn't really make much sense at all.

|

| (Cover by Vidmer) |

not really successful either. Dave Hanson wakes up in pain. His last memory is of a bulldozer at a construction site in Canada falling onto him. If he has been saved, this hospital room seems strange, with people making strange gestures and wearing strange clothes, and talking about strange things.

He eventually learns that he is in some other world. He has died and been reconstituted for his engineering talent -- it appears that this world is a Ptolemaic universe, complete with a physical sky on which the stars and planets and sun are fixed. The sky is cracked, and they need someone to fix it. Unfortunately, Dave Hanson isn't the right guy -- his uncle David Hanson is the engineering genius, Dave is just a computer geek.

But he makes a brave try, then is kidnapped by the opposition, which believes that it is destiny that the sky crack open, and the world "hatch" from its egg. He is accompanied by a beautiful woman who misperformed a spell and ended up spelling herself in love with him by mistake. (Alas that she is a "certified and registered virgin".) It's not clear which side is right and which wrong, but perhaps it doesn't matter, until it occurs to someone that Dave's computer knowledge, combined with magical principles and an orrery, might actually be enough to repair the sky.

This is also pretty goofy stuff, but also kind of original. It gets points for the originality, for trying something new. But in execution it is sort of slapdash, and never really convincing.