I've already posted reviews of the three of his novels that appeared in Ace Doubles, including a post one year ago today! Here are reviews of his other two novels (not counting the fixup Romance on Four Worlds from 2005, which is essentially a collection of his four "Casanova" stories from Asimov's.) These books appeared in 1971 and 1972.

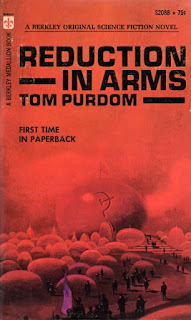

Reduction in Arms, by Tom Purdom

a review by Rich Horton

Reduction in Arms is Tom Purdom's fourth novel, published in 1971. Its subject matter is rather interesting, somewhat dated in many ways -- very 70s, though with some resonance with today's "current events".

Reduction in Arms is Tom Purdom's fourth novel, published in 1971. Its subject matter is rather interesting, somewhat dated in many ways -- very 70s, though with some resonance with today's "current events".The story is told mainly from the viewpoint of Jerry Weinberg, a US weapons inspector working in the Soviet Union. It appears to be set in the mid-80s, at a guess. A strict arms-limitation treaty has just been signed, such that both countries (and China, Britain, France, and other nuclear powers) have agreed to allow regular and sometimes random inspections of any facility that may house weapons building or research. The problem is that "weapons research" might be done is a very small area, when you consider that weapons might include tailored viruses. And indeed, Weinberg is suddenly summoned to inspect a Russian psychiatric hospital, because the Americans have learned that a distinguished microbiologist has been undergoing "treatment" there for some time. The US has information that the man has been seen in a bar -- entirely inconsistent with his supposed mental illness.

When they get to the hospital, they are denied entry to certain floors, including the microbiologist's floor, on the grounds that experimental treatments on those floors are so rigorous that any disturbance will completely ruin things. Naturally the inspectors are suspicious, but protocol requires that they go through channels. Things are further complicated by factions in both the US and Russia which oppose the disarmament treaty, and which are itching for a "incident" which will make it politically necessary that it be abrogated. So Weinberg must balance several possibilities -- that this might be staged by the Russians to embarrass the US; that this might be staged by US hardliners -- or if not staged, that a minor infraction will be fanned into something more serious for political reasons by said hardliners; that the Russians really are trying to get away with something; that everything is innocent and the US will come out with egg on its face; or some combination of the above.

The ideas here are interesting and worth thinking about, but a lot ends up not very convincing. Purdom's ideas about the future of psychiatry, in this and even more in other novels (particularly The Barons of Behavior) are downright scary but also, I think, a bit unlikely. I also found the likelihood of such an arms control treaty as described rather low -- and the danger that it could be readily circumvented by an even better hidden remote lab higher than described. Also, the book rather drags -- it's very talky for about the first half, though the second half moves much more rapidly, with plenty of action. Still, not in my opinion one of Purdom's best efforts.

The Barons of Behavior, by Tom Purdom

a review by Rich Horton

The Barons of Behavior is an interesting book on several grounds. Purdom, as I have mentioned before, is an interesting author with an interesting career shape: he

began selling SF in the late 50s, and published a dozen or so stories,

and 5 novels, through the early 70s.

The Barons of Behavior is an interesting book on several grounds. Purdom, as I have mentioned before, is an interesting author with an interesting career shape: he

began selling SF in the late 50s, and published a dozen or so stories,

and 5 novels, through the early 70s. The Barons of Behevior, from 1972, was and remains his last novel. He published two more stories at long intervals until the 90s, when he returned to the field with a vengeance -- he has published dozens of stories since 1990, most in Asimov's, many absolutely first rate.

The first thing that strikes me about The Barons of Behavior is that it is very uncommercial. Its hero is hardly admirable -- or, if admirable in many ways, he is also not very likeable, and he is shown doing many bad things. The plot is resolved ambiguously, and long before the natural end of the action. The general theme is very scary, and the "good guys" are forced to use the tactics of the bad guys, and not in very nice ways.

The "hero" is Ralph Nicholson, a psychiatrist based in Philadelphia (I believe). The book is set in either 2001 or 2003. Nicholson is concerned about the tactics of Martin Boyd, the Congressman representing Windham County in New Jersey. Boyd is using psychological profiles of every resident of his district to control their reactions and voting. He has even arranged for neighborhoods to be adjusted so that only people of a given profile live in them.

Nicholson, and his boss, another politician, believe that the only way to stop Boyd is to get him out of Congress, and the only way that can happen is to arrange for someone else to get elected. But the only way they can counteract Boyd's psych work is to do the same -- choose a candidate and slant his message in a way that matches the psych profiles of voters.

But Boyd plays dirty -- he kidnaps Nicholson, using his bought-and-paid-for police force, and threatens to use a profile of Nicholson's wife to suborn her. Will Nicholson stay the course? Will Nicholson's chosen politician go along with the not precisely ethical actions urged on him, including staged incidents designed to make voters support a "citizens' patrol", organized by the candidate? Will Nicholson's wife stay faithful? Will all this effort even be enough?

Along the way we get something of a picture of Nicholson's character and history, and of the civic background of his time. Perhaps all this is a bit sketchy, but it's of some interest. Notably the sexual mores are loose and a bit weird seeming -- in particularly Nicholson's pursuit of his wife is very calculated, including carefully planned affairs with other women. All this ties into the psychological themes of the novel, of course.

For all the interesting ideas and considerable ambition, however, the book isn't quite successful. It really doesn't overcome its odd (presumably purposefully so) truncated structure and its unlikable characters. But I think the ambition and honest of the effort deserves admiration.