On what would have been Charles V. De Vet's 107th birthday, I'm reposting one of my personal favorites among my Ace Double reviews -- not because the books are my favorites, but because I had a lots of fun tracking down the extended history of the De Vet/MacLean novel and its sequel.

King of the Fourth Planet is about 43,000 words long. Cosmic Checkmate is about 33,000 words, and it has a complicated publishing history. It's an expansion (by a factor of roughly 2) of the novelette "Second Game" (Astounding, March 1958), a Hugo nominee and still a fairly well-known story. The novel was reissued in 1981 by DAW with further expansions, to some 56,000 words, now retitled Second Game after the novelette. (A much better title!) Finally, De Vet by himself wrote a sequel published in the February 1991 Analog, called "Third Game".

|

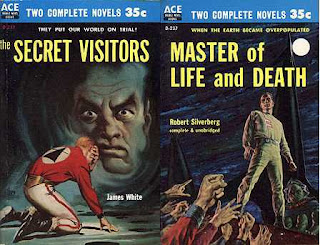

| (Covers by Ed Emswhiller and Ed Valigursky) |

Neither of the authors of Cosmic Checkmate was terribly prolific, indeed, their quantity of output is strikingly similar: 30 or 40 stories and one solo novel each. De Vet (1911-1997) began publishing in 1950, and through 1962 published a couple of dozen stories. Over the next couple of decades he published far less often, just 8 more stories according to the ISFDB, several in Ted White's mid-70s Amazing, with "Third Game" his last story. He published just one additional novel, Special Feature (1975), another expansion of a 1958 Astounding novelette ("Special Feature", May 1958). MacLean (b. 1925), is deservedly the better known. She is this year's SFWA Writer Emeritus (2003). She began publishing in 1949, and has had a story in Analog as recently as "Kiss Me" (February 1997), which made the Hartwell Year's Best #3. Her best-known story is almost certainly "The Missing Man" (Analog, March 1971), which won a Nebula for Best Novella, and which was expanded to her only solo novel, Missing Man (1975). (She has published one other collaborative novel, Dark Wing, (1979), with Carl West, which I haven't seen but which appears to be a YA Fantasy.) Other stories such as "Contagion" (1950), "Pictures Don't Lie" (1951), "The Snowball Effect" (1952), "The Diploids" (1953), "The Trouble With You Earth People" (1968), and "The Kidnapping of Baroness 5" (1995), gained considerable notice.

Robert Moore Williams (1907-1977) was a fairly regular writer for the SF magazines beginning in the late 30s, and ending in 1965-1966 with a sudden spurt of 4 stories for Fred Pohl's If after roughly a decade of publishing no short fiction. He also published quite a few novels in the field, including 11 Ace Double halves (in 9 books -- two of his halves were story collections that backed his own novels). Based on what I've read of his work, he wasn't really very good, and presumably as a result he is all but forgotten now. He might have been best known for a series of Edgar Rice Burroughs-like stories about heroes named Zanthar and Jongor, which appeared from Lancer and Popular Library from 1966 through 1970. (The Jongor books were reprints (perhaps expanded) of stories from Fantastic Adventures between 1940 and 1951, and the 1970 editions had Frazetta covers, which I am pretty sure I saw back in the day, though I never read them.)

King of the Fourth Planet is pretty straightforward SF. John Rolf is a former executive of the Company for Planetary Development who has repented of his unethical ways, and moved to Mars, divorcing his wife and leaving her with their young daughter when she refuses to accompany him. Rolf lives on the giant mountain Suzusilam, where most of the Martians live. The mountain (perhaps a "prediction" of Olympus Mons, which wasn't discovered until 1971) is divided into seven levels, on each of which live Martians of increasing "civilizedness". The fourth level is the home of the Martians at roughly Earth levels of development. The seventh level is reputedly home only to the mysterious King of the Red Planet, a Martian of incredible powers who "holds the mountain in his hand". Rolf lives on the fourth level, home to many mechanical geniuses, and he himself is working on a telepathy machine, which he hopes will solve humanity's problems by giving all people understanding of others. He is assisted at times by his friend Thallen from the fifth level. Just as he completes his machine, a Human spaceship lands, and Rolf senses the evil mind of the Company executive controlling the spaceship. Before you know it, this man, Jim Hardesty, shows up at Rolf's doorstep, demanding his assistance in cheating the Martians. Rolf refuses, whereupon Hardesty reveals that he has hired Rolf's daughter as his secretary (i.e. potential sex slave), but Rolf, with his daughter's help, continues to refuse. Soon a man shows up who has fallen in love with Rolf's daughter, but then Hardesty mounts an attack on the Martians, the daughter is kidnapped, Rolf is injured and his mind becomes detached from his body, and all leads to a confrontation on the seventh level with the mysterious King.

It's mostly a pretty bad book. Some of it is slapdash, such as having people run up and down this presumably huge mountain in no more than a couple of hours. The action develops too quickly, and not logically, and plot threads and ideas that showed promise (or not) are often as not brushed aside without resolution, or with unsatisfactory resolution. There are some nice bits -- the climactic scene at the top of the mountain is pretty impressive in parts, the advanced Martian tech represented by "abacuses" that play musical notes which cause healing and other powers is really kind of nicely depicted, the ethical message advanced, if crudely put, seems deeply felt and not unreasonable. Still -- not really a book worth attention. And not any reason to reconsider Williams' place in the canon.

Second Game is rather better. It's the story of the planet Velda, which has just been discovered by the Earth-centered Ten Thousand Worlds. After warning that they wanted no contact, the Veldians destroyed the Fleet that Earth sent anyway. The narrator, a chess champion, has learned that the Veldians base their society around proficiency in a Game, somewhat like Chess but more complicated. (Details are sketchy, but it is played on a 13x13 board, and each player controls 26 pieces, or "pukts".) Equipped with an "annotator", sort of an AI addition to his brain, the narrator learns the Game and comes to Velda to challenge all comers. He puts up a sign saying "I'll beat you the Second Game". And after probing the opponents' weaknesses by playing the first game, he does indeed beat them the second time. He finally draws the attention of Kalin Trobt, a high official and thus a proficient Game player. After the most difficult Game yet, the narrator again prevails, but Trobt perceives that he is a human, and arrests him as a spy.

Veldian society is predicated on exaggerated concepts of honor, and on absolute honesty. So the narrator is simply placed under house arrest at Trobt's house, though he is told that he will die, in the "Final Game". Over the next couple of weeks, the narrator and Trobt become friends, but the narrator's fate remains sealed. Both probe each other for secrets about their respective societies, and in particular a biological reason for much of the Veldian situation is revealed. Finally the narrator comes up with a surprising solution to his problem, and to Velda's problem, and eventually to the Ten Thousand Worlds' problem.

This short novel is a quick, entertaining, and generally absorbing read. It's not quite convincing -- the Game is marginally plausible, but not the narrator's proficiency. The Veldian social structure, and military prowess, both seem rather artificial. I didn't quite buy the biological problem at the heart of Veldian society either. Indeed, Veldqan biology as portrayed seems truly implausible -- I can't believe this race would survive! Other problems were lesser, such as the magical ability of Veldians and Humans to interbreed (this problem could easily have been finessed by a reference to panspermia or a lost colony or something, but instead the Veldians are supposed to be true aliens). Still, overall the story is enjoyable and thoughtful.

I read the novelette "Second Game" and the novel Cosmic Checkmate back to back. It's interesting how closely they resemble each other. The novel is not an extension, but an organic expansion, without even much in the way of added subplots. There is a somewhat unconvincing love interest for the narrator in the novel which is absent in the novelette.* Otherwise the expansions are all fleshed out scenes, added explanations. I think it actually works pretty well -- the novel does not seem padded.

I followed this by reading the 1981 DAW novel, Second Game. This is longer still, and it also features some curious changes. The changes include: changing the planet's name from Velda to Veldq (presumably to make it more "alien", and also perhaps to avoid sounding like a woman's name), changing the narrator's name from Robert O. Lang to Leonard Stromberg (a change I utterly fail to understand unless perhaps that was the original name, and John Campbell insisted on a more Anglo-Saxon lead character), and adding a new social group to Veldq society, the Kismans, low-status merchants. Further changes include more bald exposition of the Ten Thousand Worlds' situation, an altered (and not terribly believable) explanation for the Veldqan level of technology, a hugely expanded subplot about the narrator's Veldqan love interest, including some rather embarrassing sex scenes (and a revised account of the relationship of the sexes on Veldq), and a fair amount of small interpolations, fleshing out details.

On balance I think I prefer the shorter 1962 novel to the 1981 expansion: some of the 1981 additions are sensible fleshing out, but some are silly. The expanded love story is logical and fills in something missing in the 1962 version, but it's not very well done. Other additions, such as the Kismans and the new explanation of Veldqan tech, seem either superfluous or wrong. I wouldn't say, however, that the 1981 version feels padded -- the novelette, in retrospect, seems somewhat rushed, and I would have to say the story basically supports at least 50,000 words.

Finally I went ahead and read the 1991 novelette sequel, by De Vet alone, "Third Game". This is about 15,000 words long. It's set 23 years after the main action of Second Game. There are severe social problems on Veldq, and Leonard Stromberg's half-Veldqan son, Kalin Stromberg, comes to the planet to try to help. After some more harsh evidence of the silly over-violent Veldqan society, and another sometimes embarrassing highly sexed romance, which involved dealing fairly with the oppressed Kisman minority**, and, get this (shades of Asimov's The Stars Like Dust) -- adopt a constitution modelled on the US constitution. It's really a very bad story.

(*There was a curious brief mention of the girl who becomes the narrator's love interest in the novelette -- on reading that, bells went off in my head, and I was surprised that she did not reappear in the story. Which makes me wonder if the novelette wasn't cut before publication, as opposed to the novel being a later expansion.)

(**The Kismans are important in this story as they weren't in the 1981 Second Game, making me wonder if De Vet hadn't already written a version of "Third Game" when he (and MacLean) expanded Cosmic Checkmate to Second Game.)