The Prodigal Troll, by Charles Coleman Finlay

a review by Rich Horton

Charles Coleman Finlay was born July 1, 1964, so I am exhuming this review I did of his first novel, The Prodigal Troll, for his 54th birthday. Charlie, who has been using the form of his name "C. C. Finlay" as a byline in recent years, has been editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction since 2015. He's been publishing short fiction, and a few novels, since 2001 (his first a story in F&SF told all in footnotes, and called, appropriately, "Footnotes"). I think he's an excellent writer of fiction, and I hope his editorial duties don't wholly suppress his auctorial voice -- so far, alas, we haven't seen any new fiction since 2015, so he seems perhaps to be following the path of Gardner Dozois, if not quite that of John W. Campbell, Jr. And, that said, I've been really pleased with his work at F&SF.

The Prodigal Troll was his first novel, published in 2005. It was expanded from some previously published short stories. A couple appeared in F&SF, and one interesting one appeared in Black Gate. This last, "The Nursemaid's Suitor", is actually the first part of the novel, but slightly -- though very significantly -- changed. As Finlay notes, it's the story that he would have told if the story was meant to be about the nursemaid and her suitor, rather than about Claye/Maggot, the actual protagonist of the novel.

In a fairly standard (but nicely presented) medievaloid fantasy world, Lord Gruethrist's domains are, at the open, taken over by an ambitious rival. Or, I should say, Lady Gruethrist -- in this world, all land is owned by women. Men fight wars and otherwise act for their wives, but only women can own property. Well, women and eunuchs (who are addressed as "she" and "her".) Lord and Lady Gruethrist have an infant son, Claye, and he has detailed one of his best warriors to help the child's nursemaid to escape to safety. The warrior in question, it turns out, has an unrequited passion for the nursemaind. But on their escape they learn that the situation is more dire than they expected -- it seems the political winds blow entirely against Lord Gruethrist, and all his allies are either dead or subverted. They try to make a home in an deserted cottage, but come to grief -- however, the child survives, because he is adopted by a troll.

Trolls, it seems, are an endangered humanoid species, living in the mountains. Claye, now called Maggot, is raised as a troll, but his differences soon become apparent. His good heart and intelligence serve him in good stead, against the suspicions of the dwindling bands of trolls -- victims of human incursion and their own inflexibility. Eventually Maggot comes out of the mountains, where he sees a woman who completely entrances him. Much of the rest of the novel concerns his fumbling attempts to attract her attention, leading to involvement in a human war, and eventually in corrupt human politics. The resolution involves some expected but satisfying coincidences, and an honest and not standard conclusion -- which quite effectively closes the novel's story but leaves open the possibility (but not necessity) of sequels.

It turns out, to be sure, that there were no sequels, and only three further novels, the "Traitor to the Crown" trilogy of fantasies set during the American Revolution. But Finlay's short fiction has been consistently excellent, and I will include a selection of my reviews of his work in another blog post.

Sunday, July 1, 2018

Wednesday, June 27, 2018

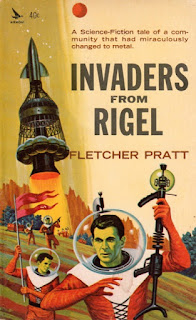

A Mercifully Forgotten SF Novel: Invaders from Rigel, by Fletcher Pratt

A Mercifully Forgotten SF Novel: Invaders from Rigel, by Fletcher Pratt

At one time I wondered if it would make sense to compile a list of elephant-like intelligent aliens in SF stories. This was about when Mike Resnick published "The Elephants on Neptune" (which I hated). There are those beasties in Niven&Pournelle's Footfall, which I've never been able to read. And there are the mammoths in Stephen Baxter's awful Silverhair and sequels. Weren't there intelligent elephants in Silverberg's Downward to the Earth (at least I thought that was pretty good)?

At one time I wondered if it would make sense to compile a list of elephant-like intelligent aliens in SF stories. This was about when Mike Resnick published "The Elephants on Neptune" (which I hated). There are those beasties in Niven&Pournelle's Footfall, which I've never been able to read. And there are the mammoths in Stephen Baxter's awful Silverhair and sequels. Weren't there intelligent elephants in Silverberg's Downward to the Earth (at least I thought that was pretty good)?

Any others?

So, the record of elephants in SF is maybe not so great, eh? And perhaps the WORST of all SF elephant stories is Fletcher Pratt's Invaders from Rigel, which I read and reviewed about the same time as Resnick's story appeared. I bought the book used a long time ago, in part because of Pratt's reputation (mainly, perhaps, derived from his de Camp collaborations). Danger signs, however, were immediately apparent. The book was published in 1960, and Pratt died in 1956. It was published by the salvage imprint Airmont, famous for publishing some dreadful stuff, though also some of de Camp's Krishna stories.

At first I thought it a late novel by Pratt, but that is only because the book came out in 1960. However, it was first published as "The Onslaught from Rigel", in Wonder Stories Quarterly, Winter 1931. It was reprinted in a 1950 edition of Wonder Story Annual which I assume was a reprint publication featuring backlist stuff from Wonder Stories.

I thought Pratt was a good writer. I thought that because of his de Camp collaborations. I am also told that later stuff like Double Jeopardy and especially The Well of the Unicorn is OK. Well maybe. But when he wrote for the pulps in the '30s he was irredeemably awful. I had earlier read Alien Planet, first published as "A Voice Across the Years" in the Winter 1932 Amazing Stories Quarterly, listed there as a collaboration with I. M. Stephens (who was his wife, Inga Stephens Pratt, a quite significant illustrator). Inexplicably, Ace reprinted this book as late as 1973. That book was awful, though oddly ambitious in being a rather satirical look at humans and their politics. Ham-handedly satirical, mind you, but at least it sort of tried. Invaders from Rigel doesn't even try anything so daring.

The story opens with one Murray Lee waking in his New York Penthouse. He soon realizes he is all metal. His roommate is as well. They tromp about the city for a bit, finding a few more live metal people, and many dead ones. This doesn't seem to bother them much. Before long alien birdlike creatures are attacking, and some people are carried away by the birds. It turns out that a comet just crashed with the Earth. That must have turned everybody to metal. Jokes are made about how they like to drink motor oil now, and their "food" is electric current. But the birds are a problem: they seem to be intelligent and malevolent. After trying to activate a destroyer, they are discovered by some Australians, who have not been turned to metal, though their blood has cobalt instead of iron now, so they are colored blue. The metal Americans join with the Australians to fight the bird menace, but it soon turns out that the real menace is a race of elephant-beings from Rigel, who are using the metal men, as well as metal apes, as slaves to harvest "pure light" from the core of the Earth.

Right.

The humans start to fight the Rigellians, but the aliens have a "pure light" weapon. Then a new character is introduced: a pilot who was captured by the elephants. He managed to escape (his ordeal is given several chapters), carrying the knowledge that lead blocks the alien super ray. Yeah. The novel concludes with a number of chapters of arms escalation, as the humans invent anti-gravity (because gravity is just like electricity, and so basically, as described, antigravity can be produced by ionization). Pointless to continue. By the end, the elephants have been vanquished (whoda thunk it?), and the metal people returned to normal. Also, there are a couple of totally unconvincing and uninvolving love affairs.

Oh, and most of the world's population is dead, and nobody really cares.

A couple of quotes which struck me particularly:

"I've got it, folks!" he cried. "A gravity beam!"

[chapter break, natch!]

"A gravity beam!" they ejaculated together, in tones ranging from incredulity to simple puzzlement.

"What's that?"

"Well, it'll take a bit of explaining but I'll drop out the technical part of it." [I'll bet you will!]

[some blather about how light and matter and electricity and gravity are all the same. Einstein said so, right!]

then:

"What was it in chemical atoms [as opposed to the other kind, I guess] that was weight? It's the positive charge, isn't it? ... Now if we can just find some way to pull some negative charges loose ..."

See? Antigravity by ionisation! If we only knew!

Later on one of the metal women is trapped with one of the metal men in a prison. They are a couple of cages away. He needs a safety pin, and she has one. So: "She swung with that underarm motion that is the nearest any woman can come to a throw." ! Let's tell Dot Richardson!

Oh, well, silly to complain further, or at all really. I'm sure Platt wrote this in about two days.

At one time I wondered if it would make sense to compile a list of elephant-like intelligent aliens in SF stories. This was about when Mike Resnick published "The Elephants on Neptune" (which I hated). There are those beasties in Niven&Pournelle's Footfall, which I've never been able to read. And there are the mammoths in Stephen Baxter's awful Silverhair and sequels. Weren't there intelligent elephants in Silverberg's Downward to the Earth (at least I thought that was pretty good)?

At one time I wondered if it would make sense to compile a list of elephant-like intelligent aliens in SF stories. This was about when Mike Resnick published "The Elephants on Neptune" (which I hated). There are those beasties in Niven&Pournelle's Footfall, which I've never been able to read. And there are the mammoths in Stephen Baxter's awful Silverhair and sequels. Weren't there intelligent elephants in Silverberg's Downward to the Earth (at least I thought that was pretty good)? Any others?

So, the record of elephants in SF is maybe not so great, eh? And perhaps the WORST of all SF elephant stories is Fletcher Pratt's Invaders from Rigel, which I read and reviewed about the same time as Resnick's story appeared. I bought the book used a long time ago, in part because of Pratt's reputation (mainly, perhaps, derived from his de Camp collaborations). Danger signs, however, were immediately apparent. The book was published in 1960, and Pratt died in 1956. It was published by the salvage imprint Airmont, famous for publishing some dreadful stuff, though also some of de Camp's Krishna stories.

At first I thought it a late novel by Pratt, but that is only because the book came out in 1960. However, it was first published as "The Onslaught from Rigel", in Wonder Stories Quarterly, Winter 1931. It was reprinted in a 1950 edition of Wonder Story Annual which I assume was a reprint publication featuring backlist stuff from Wonder Stories.

I thought Pratt was a good writer. I thought that because of his de Camp collaborations. I am also told that later stuff like Double Jeopardy and especially The Well of the Unicorn is OK. Well maybe. But when he wrote for the pulps in the '30s he was irredeemably awful. I had earlier read Alien Planet, first published as "A Voice Across the Years" in the Winter 1932 Amazing Stories Quarterly, listed there as a collaboration with I. M. Stephens (who was his wife, Inga Stephens Pratt, a quite significant illustrator). Inexplicably, Ace reprinted this book as late as 1973. That book was awful, though oddly ambitious in being a rather satirical look at humans and their politics. Ham-handedly satirical, mind you, but at least it sort of tried. Invaders from Rigel doesn't even try anything so daring.

The story opens with one Murray Lee waking in his New York Penthouse. He soon realizes he is all metal. His roommate is as well. They tromp about the city for a bit, finding a few more live metal people, and many dead ones. This doesn't seem to bother them much. Before long alien birdlike creatures are attacking, and some people are carried away by the birds. It turns out that a comet just crashed with the Earth. That must have turned everybody to metal. Jokes are made about how they like to drink motor oil now, and their "food" is electric current. But the birds are a problem: they seem to be intelligent and malevolent. After trying to activate a destroyer, they are discovered by some Australians, who have not been turned to metal, though their blood has cobalt instead of iron now, so they are colored blue. The metal Americans join with the Australians to fight the bird menace, but it soon turns out that the real menace is a race of elephant-beings from Rigel, who are using the metal men, as well as metal apes, as slaves to harvest "pure light" from the core of the Earth.

Right.

The humans start to fight the Rigellians, but the aliens have a "pure light" weapon. Then a new character is introduced: a pilot who was captured by the elephants. He managed to escape (his ordeal is given several chapters), carrying the knowledge that lead blocks the alien super ray. Yeah. The novel concludes with a number of chapters of arms escalation, as the humans invent anti-gravity (because gravity is just like electricity, and so basically, as described, antigravity can be produced by ionization). Pointless to continue. By the end, the elephants have been vanquished (whoda thunk it?), and the metal people returned to normal. Also, there are a couple of totally unconvincing and uninvolving love affairs.

Oh, and most of the world's population is dead, and nobody really cares.

A couple of quotes which struck me particularly:

"I've got it, folks!" he cried. "A gravity beam!"

[chapter break, natch!]

"A gravity beam!" they ejaculated together, in tones ranging from incredulity to simple puzzlement.

"What's that?"

"Well, it'll take a bit of explaining but I'll drop out the technical part of it." [I'll bet you will!]

[some blather about how light and matter and electricity and gravity are all the same. Einstein said so, right!]

then:

"What was it in chemical atoms [as opposed to the other kind, I guess] that was weight? It's the positive charge, isn't it? ... Now if we can just find some way to pull some negative charges loose ..."

See? Antigravity by ionisation! If we only knew!

Later on one of the metal women is trapped with one of the metal men in a prison. They are a couple of cages away. He needs a safety pin, and she has one. So: "She swung with that underarm motion that is the nearest any woman can come to a throw." ! Let's tell Dot Richardson!

Oh, well, silly to complain further, or at all really. I'm sure Platt wrote this in about two days.

Thursday, June 21, 2018

A Forgotten Ace Double: The Nemesis from Terra, by Leigh Brackett/Collision Course, by Robert Silverberg

Ace Double Reviews, 55: The Nemesis from Terra, by Leigh Brackett/Collision Course, by Robert Silverberg (#F-123, 1961, $0.40)

Here's an Ace Double consisting of two all but forgotten books -- by two writers who are anything but forgotten! I've written about both Brackett and Silverberg before, so I'll just jump right into discussing the books.

The Nemesis from Terra is about 42,000 words long. It is the same story as "Shadow Over Mars", from the Fall 1944 Startling Stories. I haven't seen that magazine (and I don't think the story has otherwise been reprinted, except perhaps in the recent Haffner Press collection of early Brackett). So I don't know if the Ace Double version is expanded or otherwise changed.

It's set on a Mars uneasily shared by human colonists and Martians. There is a nascent movement among the Martians for rebellion. The humans, meanwhile, are increasingly controlled by the "Company", and the notional government, which is supposed to support Martian as well as human interests, seems powerless. Rick, the hero, is being chased by Company goons as the story opens -- they will put him to work in the mines. But first he encounters an ancient Martian woman, who sees Rick's "shadow over Mars". Rick then kills her (admittedly in self-defense), making him an enemy to Martians.

Finally captured, he goes to work in the mines. But he manages an escape, and links up with the beautiful Mayo McCall, who has been working with a Martian-rights group. He makes another enemy, too, in the Company thug Jaffa Storm. Mayo and he escape and encounter another Martian race, a winged race. Mayo urges him to join the Martian-rights effort, but Rick is more interested in revenge.

Rick is captured by the Martians, including their boy King, and he is punished for his earlier murder. But a Martian rebellion fails utterly. Rick then gains influence, and begins to rally Martians and oppressed humans to his side. Meanwhile Jaffa Storm has murdered his way to the top of the Company, and he has also captured Mayo McCall. Rick's rebellion is successful, but he is again betrayed, and his destiny is resolved in a journey to the North Pole home of the Martian "Thinkers", where Jaffa Storm has fled with Mayo McCall.

It's decent work, early Brackett in more of a tough and cynical mode than the poetic mode she later found. It's interesting, too, in its realpolitik take on the Martian rebellion, and on Rick's ultimate place in civilized society. It's not quite clear that it fits at all well into Brackett's eventual semi-coherent Martian "mythos" -- many of the names of cities are familiar, but the general shape of things doesn't seem to jibe with, say, The Sword of Rhiannon. (Not that this is really a problem.)

Collision Course is about 47,000 words long. It is expanded from a novella in the July 1959 Amazing. The novel was first published in hardcover by the low end firm Thomas Bouregy, in 1961. Presumably this text is unchanged from the hardcover, as the cover says "Complete & Unabridged".

The Earth of several hundred years in the future is ruled by a technocratic oligarchy. Humans have expanded into space, using STL ships to reach new worlds, and matter transmitters for instantaneous travel to already discovered places. The Technarch McKenzie, one of the thirteen-member ruling council, has sponsored an FTL project which has finally borne fruit. But the first FTL ship returns with shocking news: the planet they have discovered is already occupied by aliens of a similar level of development.

The Technarch immediately decides to send a group of experts to negotiate with the aliens -- the first intelligent aliens to be discovered. They have orders to divvy up the galaxy fairly. This small group is nominally led by Dr. Martin Bernard, an expert on Sociometrics, and it includes one of his chief rivals, the New Puritan Thomas Havig. The trip out to the new planet is occupied with a certain amount of bickering between the members of the negotiating team.

But once on the planet, after some good work in setting up communication with the apparently very hierarchical aliens, the team hits a deadlock. The aliens chiefs refuse to negotiate, and claim all the galaxy (except for the small portion occupied by humans) for themselves. It seems war is inevitable. But the journey home is interrupted by something completely unexpected -- something which changes the view of the universe for both the humans and the aliens.

This is Silverberg in a very earnest mood, dealing with some fairly serious issues. However, the story doesn't really live up to its potential. It's rather slow paced, the characters are not quite believable, the story itself is just not interesting enough. I would characterize it (in retrospect!) as the work of an author who was determined to do more serious work, but who was not yet up to it.

Here's an Ace Double consisting of two all but forgotten books -- by two writers who are anything but forgotten! I've written about both Brackett and Silverberg before, so I'll just jump right into discussing the books.

|

| (Covers by Ed Valigursky and Ed Emshwiller) |

The Nemesis from Terra is about 42,000 words long. It is the same story as "Shadow Over Mars", from the Fall 1944 Startling Stories. I haven't seen that magazine (and I don't think the story has otherwise been reprinted, except perhaps in the recent Haffner Press collection of early Brackett). So I don't know if the Ace Double version is expanded or otherwise changed.

It's set on a Mars uneasily shared by human colonists and Martians. There is a nascent movement among the Martians for rebellion. The humans, meanwhile, are increasingly controlled by the "Company", and the notional government, which is supposed to support Martian as well as human interests, seems powerless. Rick, the hero, is being chased by Company goons as the story opens -- they will put him to work in the mines. But first he encounters an ancient Martian woman, who sees Rick's "shadow over Mars". Rick then kills her (admittedly in self-defense), making him an enemy to Martians.

|

| (Cover by Earle Bergey) |

Rick is captured by the Martians, including their boy King, and he is punished for his earlier murder. But a Martian rebellion fails utterly. Rick then gains influence, and begins to rally Martians and oppressed humans to his side. Meanwhile Jaffa Storm has murdered his way to the top of the Company, and he has also captured Mayo McCall. Rick's rebellion is successful, but he is again betrayed, and his destiny is resolved in a journey to the North Pole home of the Martian "Thinkers", where Jaffa Storm has fled with Mayo McCall.

It's decent work, early Brackett in more of a tough and cynical mode than the poetic mode she later found. It's interesting, too, in its realpolitik take on the Martian rebellion, and on Rick's ultimate place in civilized society. It's not quite clear that it fits at all well into Brackett's eventual semi-coherent Martian "mythos" -- many of the names of cities are familiar, but the general shape of things doesn't seem to jibe with, say, The Sword of Rhiannon. (Not that this is really a problem.)

Collision Course is about 47,000 words long. It is expanded from a novella in the July 1959 Amazing. The novel was first published in hardcover by the low end firm Thomas Bouregy, in 1961. Presumably this text is unchanged from the hardcover, as the cover says "Complete & Unabridged".

|

| (Cover by Albert Nuetzell) |

The Technarch immediately decides to send a group of experts to negotiate with the aliens -- the first intelligent aliens to be discovered. They have orders to divvy up the galaxy fairly. This small group is nominally led by Dr. Martin Bernard, an expert on Sociometrics, and it includes one of his chief rivals, the New Puritan Thomas Havig. The trip out to the new planet is occupied with a certain amount of bickering between the members of the negotiating team.

But once on the planet, after some good work in setting up communication with the apparently very hierarchical aliens, the team hits a deadlock. The aliens chiefs refuse to negotiate, and claim all the galaxy (except for the small portion occupied by humans) for themselves. It seems war is inevitable. But the journey home is interrupted by something completely unexpected -- something which changes the view of the universe for both the humans and the aliens.

This is Silverberg in a very earnest mood, dealing with some fairly serious issues. However, the story doesn't really live up to its potential. It's rather slow paced, the characters are not quite believable, the story itself is just not interesting enough. I would characterize it (in retrospect!) as the work of an author who was determined to do more serious work, but who was not yet up to it.

Birthday Review: Atonement, by Ian McEwan

Birthday Review: Atonement, by Ian McEwan

a review by Rich Horton

Ian McEwan was born on 21 June 1948, so in honor of his 70th birthday, I am resurrecting this piece I wrote for my SFF.net newsgroup long ago, on his best-known novel.

Ian McEwan is one of the most highly-regarded novelists working today, and with damn good reason. I first encountered him, oddly enough, in the pages of Ted White's Fantastic, back in the mid-70s, with a story called "Solid Geometry". That was a very odd and quite excellent story, and McEwan's name stuck in my mind. So I later read his first story collection, First Love, Last Rites, very fine work. I kind of lost touch for a while, though I noticed that he was beginning to be widely praised. I did eventually read his creepy and scary first novel, The Cement Garden, about a nearly feral set of siblings living alone in a decaying neighborhood. That novel, along with the stories in First Love, Last Rites, and later works like The Child in Time (about the kidnapping of a three year old) gave him a reputation as sort of a contemporary psychological horror writer, a reputation which it seems to me slightly retarded his overall recognition. (That is to say, he was highly praised, but often with a sort of caveat, suggesting that he relied a lot on shock for his effects. Or so it seemed to me.) But eventually he seemed to have become established as a contender for "Best Contemporary British Writer". He's been nominated four times for the Booker (or Man Booker) Prize, and he won once for a very short novel, Amsterdam (possibly the slightest of his short listed novels). Atonement was short listed for the 2001 prize, but it lost to Peter Carey's The True History of the Kelly Gang.

Atonement is an outstanding novel. (Much better than Amsterdam, which is fine but as I said slight.) It is the story of one day in the life of 13 year old Briony Tallis, and the terrible crime she commits, and her eventual attempt at "atonement". Briony is an aspiring writer (and, we are aware from the start, she will eventually be a very highly regarded novelist), and she is planning to present a play for her beloved older brother Leon, visiting from London, on this day in 1935. The first half of the book presents the events of that day through the intertwined perceptions of several people: Briony; her older sister Cecilia, who has just finished at Cambridge; their charlady's son, Robbie, who has also finished at Cambridge and will be trying for medical school (sponsored by Mr. Tallis); and Briony's mother Emily Tallis, an invalid whose husband stays away and is clearly cheating on her. The other key characters are the Quinceys: 15 year old Lola and 9 year old twin boys Jackson and Pierrot, who have come to stay with the Tallises while their parents (Emily's sister and her husband) go through a divorce.

Briony recruits her cousins to act in her play but they seem ready to ruin it. Robbie and Cecilia, long friends from having grown up together, begin to discover a deeper attraction. The amiable Leon shows up with his crude and rich friend Paul Marshall. Dinner ends suddenly with the young boys running away, and a terrible event while searching for them is compounded by Briony's "crime", which I won't reveal but is truly wrenching, truly a "crime", but in a way understandable.

The novel then jumps forward 5 years to the beginning of the War, specifically the retreat from Dunkirk, and the effects of Briony's crime are revealed. Briony herself begins to try to atone ... Finally, in 1999 the aging Briony, a lionized novelist, reflects on her secrets, and on her final attempt at atonement.

It's really excellent stuff -- terribly wrenching, also sweetly moving, quite exciting. The view of the events at Dunkirk is a very effective. Briony, Robbie, and Cecilia are captured with exactness and honesty. The prose is very fine, very balanced and elegant. The real thing.

It has since, of course, been made into a very well-received movie, starring Keira Knightley and James McAvoy. I did like the film. I will note that a film based on his short novel On Chesil Beach (which I thought pretty good) is due this year.

a review by Rich Horton

Ian McEwan was born on 21 June 1948, so in honor of his 70th birthday, I am resurrecting this piece I wrote for my SFF.net newsgroup long ago, on his best-known novel.

Ian McEwan is one of the most highly-regarded novelists working today, and with damn good reason. I first encountered him, oddly enough, in the pages of Ted White's Fantastic, back in the mid-70s, with a story called "Solid Geometry". That was a very odd and quite excellent story, and McEwan's name stuck in my mind. So I later read his first story collection, First Love, Last Rites, very fine work. I kind of lost touch for a while, though I noticed that he was beginning to be widely praised. I did eventually read his creepy and scary first novel, The Cement Garden, about a nearly feral set of siblings living alone in a decaying neighborhood. That novel, along with the stories in First Love, Last Rites, and later works like The Child in Time (about the kidnapping of a three year old) gave him a reputation as sort of a contemporary psychological horror writer, a reputation which it seems to me slightly retarded his overall recognition. (That is to say, he was highly praised, but often with a sort of caveat, suggesting that he relied a lot on shock for his effects. Or so it seemed to me.) But eventually he seemed to have become established as a contender for "Best Contemporary British Writer". He's been nominated four times for the Booker (or Man Booker) Prize, and he won once for a very short novel, Amsterdam (possibly the slightest of his short listed novels). Atonement was short listed for the 2001 prize, but it lost to Peter Carey's The True History of the Kelly Gang.

Atonement is an outstanding novel. (Much better than Amsterdam, which is fine but as I said slight.) It is the story of one day in the life of 13 year old Briony Tallis, and the terrible crime she commits, and her eventual attempt at "atonement". Briony is an aspiring writer (and, we are aware from the start, she will eventually be a very highly regarded novelist), and she is planning to present a play for her beloved older brother Leon, visiting from London, on this day in 1935. The first half of the book presents the events of that day through the intertwined perceptions of several people: Briony; her older sister Cecilia, who has just finished at Cambridge; their charlady's son, Robbie, who has also finished at Cambridge and will be trying for medical school (sponsored by Mr. Tallis); and Briony's mother Emily Tallis, an invalid whose husband stays away and is clearly cheating on her. The other key characters are the Quinceys: 15 year old Lola and 9 year old twin boys Jackson and Pierrot, who have come to stay with the Tallises while their parents (Emily's sister and her husband) go through a divorce.

Briony recruits her cousins to act in her play but they seem ready to ruin it. Robbie and Cecilia, long friends from having grown up together, begin to discover a deeper attraction. The amiable Leon shows up with his crude and rich friend Paul Marshall. Dinner ends suddenly with the young boys running away, and a terrible event while searching for them is compounded by Briony's "crime", which I won't reveal but is truly wrenching, truly a "crime", but in a way understandable.

The novel then jumps forward 5 years to the beginning of the War, specifically the retreat from Dunkirk, and the effects of Briony's crime are revealed. Briony herself begins to try to atone ... Finally, in 1999 the aging Briony, a lionized novelist, reflects on her secrets, and on her final attempt at atonement.

It's really excellent stuff -- terribly wrenching, also sweetly moving, quite exciting. The view of the events at Dunkirk is a very effective. Briony, Robbie, and Cecilia are captured with exactness and honesty. The prose is very fine, very balanced and elegant. The real thing.

It has since, of course, been made into a very well-received movie, starring Keira Knightley and James McAvoy. I did like the film. I will note that a film based on his short novel On Chesil Beach (which I thought pretty good) is due this year.

Sunday, June 17, 2018

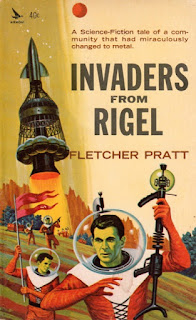

Ace Double Reviews, 5: Alpha Centauri - Or Die!, by Leigh Brackett/Legend of Lost Earth, by G. McDonald Wallis

Ace Double Reviews, 5: Alpha Centauri - Or Die!, by Leigh Brackett/Legend of Lost Earth, by G. McDonald Wallis (#F-187, 1963, $0.40)

Geraldine McDonald Wallis was born June 17, 1925. As far as I can determine, she is still alive (though that's hardly a definitive statement). She would be 93. In honor of her birthday, I'm reposting a review of one of her two Ace Doubles. I hated the other one (The Light of Lilith), but this one is a bit better.

Often in researching the history of these stories I find unexpected stuff. The surprise this time was when I looked up Wallis. G. McDonald Wallis's full name was Geraldine June McDonald Wallis (b. 1925). She published one other Ace Double, The Light of Lilith (1961), backed with Damon Knight's The Sun Saboteurs, (aka "The Earth Quarter", and one of Knight's greatest novellas). As far as the ISFDB knows, that's all she published. Not much of interest there, but the Locus Index revealed an interesting addition to her bibliography. As Hope Campbell, she published a Young Adult ghost story/detective story called Looking for Hamlet in 1987. Hope Campbell, it turns out, has quite an extensive career as a Young Adult author. Other titles include Liza (1965), Home to Hawaii (1967), Why Not Join the Giraffes? (1969), Meanwhile, Back at the Castle (1970), and several more. Her publisher even reprinted Legend of Lost Earth under the Hope Campbell name in 1977. (A Hope Campbell also had a story in Dime Detective Magazine in 1948, and several other stories earlier in the '40s in the romance pulps, but I don't know if that would be the same person. Maybe, but maybe not, as the first of those romance stories would have appeared when she was about 17.) Many of her books would presumably have been available to me when I was a young adult myself, but I admit I never heard of her. (According to her bio in front of this book, she was raised in "Hawaii and the Orient", and was an actress in radio, TV, and summer stock.)

Anyway, to the book at hand. Leigh Brackett is by far the more famous author, in SF circles at least. Alpha Centauri - Or Die! is a fixup of two novellas from Planet Stories, "The Ark of Mars" (September 1953) and "Teleportress of Alpha C" (Winter 1955 -- the ante-penultimate issue of that great pulp). Comparing my copies of "The Ark of Mars" and "Teleportress of Alpha C" with the Alpha Centauri - Or Die! suggests that the novel version is slightly expanded. It totals about 40,000 words. Lost Legend of Earth is about 45,000 words long.

Alpha Centauri - Or Die! is not one of Brackett's best novels. One problem is that it is fairly straightforward science fiction, without the frisson of Dunsany-esque fantastical imagery that so drives her best work. (Though there is a High Martian woman on hand. Also, one should note that Brackett did some fine work in the pure SF idiom, such as The Big Jump and The Long Tomorrow.)

This novel opens on Mars, in a future dominated by Williamsonian robots. These robots have taken over dangerous jobs such as space travel, for reasons of safety and to prevent war. Apparently humans are restricted in other ways as well. A band of humans, led by former pilot Kirby and his Martian wife Shari, refurbish an old ship, the Lucy B. Davenport, and plan an escape to Alpha Centauri. They get away, but soon they have to fight off a robot ship that chases them down. Years later, they reach Alpha Centauri, and they find an inhabitable planet. But the planet is occupied by creatures with teleporting powers. Can they make accommodation with these creatures? And can they fend off the Robot ship that has followed?

Mediocre stuff, really, though Brackett is never unreadable, and I did enjoy the book.

Legend of Lost Earth is actually a rather interesting book, though it takes an anti-technological view that I found annoying. Giles Cuchlainn is a young man on the planet Niflhel. This is a harsh planet, with little water, no plant life to speak of, industrial mills spewing soot into the air, a red sun invisible behind the soot and clouds. Doctrine holds that there are no other planets, and that men originated on Niflhel. Giles holds to this doctrine, but one night he attends a meeting of Earth Worshippers, who believe in a lovely green planet called Earth, the true home of men. There he meets an intriguing young woman, testing his loyalty to his longtime lover.

Soon he is recruited to spy on the Earth Worshippers, but his loyalty is thing. He attends another meeting and learns the story of how humans fled a destroyed Earth, ending up at Niflhel. He decides to save the Earth Worshippers from persecution, and then mysteriously finds himself on Earth. The ending is curious and rather mystical. To some extent the final surprise is predictable, but Wallis makes some unusual use of her revelations. She also incorporates some Celtic mythology It's not a great book, but it is interesting and somewhat original.

Geraldine McDonald Wallis was born June 17, 1925. As far as I can determine, she is still alive (though that's hardly a definitive statement). She would be 93. In honor of her birthday, I'm reposting a review of one of her two Ace Doubles. I hated the other one (The Light of Lilith), but this one is a bit better.

Often in researching the history of these stories I find unexpected stuff. The surprise this time was when I looked up Wallis. G. McDonald Wallis's full name was Geraldine June McDonald Wallis (b. 1925). She published one other Ace Double, The Light of Lilith (1961), backed with Damon Knight's The Sun Saboteurs, (aka "The Earth Quarter", and one of Knight's greatest novellas). As far as the ISFDB knows, that's all she published. Not much of interest there, but the Locus Index revealed an interesting addition to her bibliography. As Hope Campbell, she published a Young Adult ghost story/detective story called Looking for Hamlet in 1987. Hope Campbell, it turns out, has quite an extensive career as a Young Adult author. Other titles include Liza (1965), Home to Hawaii (1967), Why Not Join the Giraffes? (1969), Meanwhile, Back at the Castle (1970), and several more. Her publisher even reprinted Legend of Lost Earth under the Hope Campbell name in 1977. (A Hope Campbell also had a story in Dime Detective Magazine in 1948, and several other stories earlier in the '40s in the romance pulps, but I don't know if that would be the same person. Maybe, but maybe not, as the first of those romance stories would have appeared when she was about 17.) Many of her books would presumably have been available to me when I was a young adult myself, but I admit I never heard of her. (According to her bio in front of this book, she was raised in "Hawaii and the Orient", and was an actress in radio, TV, and summer stock.)

|

| (Covers by Richard Powers and Jack Gaughan) |

Alpha Centauri - Or Die! is not one of Brackett's best novels. One problem is that it is fairly straightforward science fiction, without the frisson of Dunsany-esque fantastical imagery that so drives her best work. (Though there is a High Martian woman on hand. Also, one should note that Brackett did some fine work in the pure SF idiom, such as The Big Jump and The Long Tomorrow.)

|

| (Cover by Kelly Freas) |

|

| (Cover by Kelly Freas) |

This novel opens on Mars, in a future dominated by Williamsonian robots. These robots have taken over dangerous jobs such as space travel, for reasons of safety and to prevent war. Apparently humans are restricted in other ways as well. A band of humans, led by former pilot Kirby and his Martian wife Shari, refurbish an old ship, the Lucy B. Davenport, and plan an escape to Alpha Centauri. They get away, but soon they have to fight off a robot ship that chases them down. Years later, they reach Alpha Centauri, and they find an inhabitable planet. But the planet is occupied by creatures with teleporting powers. Can they make accommodation with these creatures? And can they fend off the Robot ship that has followed?

Mediocre stuff, really, though Brackett is never unreadable, and I did enjoy the book.

Legend of Lost Earth is actually a rather interesting book, though it takes an anti-technological view that I found annoying. Giles Cuchlainn is a young man on the planet Niflhel. This is a harsh planet, with little water, no plant life to speak of, industrial mills spewing soot into the air, a red sun invisible behind the soot and clouds. Doctrine holds that there are no other planets, and that men originated on Niflhel. Giles holds to this doctrine, but one night he attends a meeting of Earth Worshippers, who believe in a lovely green planet called Earth, the true home of men. There he meets an intriguing young woman, testing his loyalty to his longtime lover.

Soon he is recruited to spy on the Earth Worshippers, but his loyalty is thing. He attends another meeting and learns the story of how humans fled a destroyed Earth, ending up at Niflhel. He decides to save the Earth Worshippers from persecution, and then mysteriously finds himself on Earth. The ending is curious and rather mystical. To some extent the final surprise is predictable, but Wallis makes some unusual use of her revelations. She also incorporates some Celtic mythology It's not a great book, but it is interesting and somewhat original.

Saturday, June 16, 2018

Ace Double Reviews, 67: The Pirates of Zan, by Murray Leinster/The Mutant Weapon, by Murray Leinster

Ace Double Reviews, 67: The Pirates of Zan, by Murray Leinster/The Mutant Weapon, by Murray Leinster (#D-403, 1959, $0.35, reissued as #66525, 1971, $0.95)

William F. Jenkins (better known in the SF field as Murray Leinster) was born on June 16, 1896, and died in 1975, just short of his 79th birthday. He was an extremely respected SF writer, known as the Dean of Science Fiction, and a Hugo winner. He wrote successfully in many other fields, and was also the inventor of the front projection process used in creating special effects. In honor of his birthday, I am reposting this review of one of his best known novels, backed with a less well known novel.

The longer and better known of these novels, The Pirates of Zan, was first published in Astounding, February through April, 1959, under the title "The Pirates of Ersatz". The cover of the February issue is perhaps one of the more famous Astounding covers. It's by Kelly Freas and shows a space pirate with a slide rule instead of a dagger in his teeth.

The Emshwiller cover for the 1959 Ace edition is not bad. The 1971 cover (by Dean Ellis, I think) is by comparison a grave disappointment. The serial version and the book version are almost the same -- there are small wording changes throughout, which I assume are due to different editing between John W. Campbell and Donald A. Wollheim. The serial version is a bit better.

The shorter novel is also an Astounding story. It was first published as "Med Service" in the August 1957 issue. It is of course one of Leinster's series of stories often called "Med Service", featuring a galactic medical organization that visits and aids colony planets with medical problems. The idea may owe much to the "René Lafayette" (L. Ron Hubbard) "Ole Doc Methusaleh" stories of a decade or so earlier, but Leinster's treatment is much preferable to Lafayette's: the Ole Doc Methusaleh stories are dreadfully executed as well as offensive.

"Med Service" the novella is about 22,000 words. The novel version (The Mutant Weapon) is quite a bit longer, at 34,000 words. It adds a couple of chapters at the end, going into much more detail about the motivations of the chief villain of the piece. I thought the story better at the shorter length.

The Pirates of Zan is really fairly minor stuff. It seems intended to be humourous, and it is much of the time, though some is just crank-turning. Our hero is a native of a pirate planet, but he wants to live an ordinary life, so he travels to a rich, settled, planet and sets up as a EE. But when his radical brilliant new power plant design is rejected, and he ends up accused of murder (for weird reasons that never make sense), he finds himself on the run. He ends up on a backward planet, and once again runs afoul of the local customs, after rescuing a beautiful girl from an abduction attempt. Upon escaping, he kidnaps a few of the locals and sets up as a pirate, but a completely non-violent one. He works an unconvincing scheme to use the threat of piracy to manipulate shipping and insurance stocks so that he can make enough money to a) pay off the locals who have become his crew, b) repay the people he pirated, c) set up a defrauded group of colonists on a new planet, and d) get rich enough himself to marry his girl back on the first planet he went to. Of course, he succeeds wildly, except for coming to realize that his ersatz piracy is vital to civilization, both for economic reasons and for romantic reasons, so he's stuck being a pirate, and also except for realizing (big surprise!) that his first girl is a boring spoiled brat but that he really loves the girl he rescued on his second planet. It's rather rambling, and it really doesn't convince, but it does pass the time pleasantly. It should be noted that it was nominated for the Best Novel Hugo.

The Mutant Weapon is probably intended a bit more seriously. The Med Service man Calhoun, hero of the overall series of Med Service stories, comes to a planet which is about ready for full colonization, intending to give it a basic inspection. It seems that the Med Service is the main organization keeping civilization together -- the Galaxy is too big, travel times too great, for a true interstellar government. When he arrives he is shocked to be attacked (by manipulation of the spaceship landing grid). He manages to escape and land in an isolated area. He and his alien pet/testbed Murgatroyd make their way towards the main city. He discovers a man who seems to have died from starvation, amidst what seems to be plenty of food. He is attacked by a nearly starving young woman, but convinces her he's not from the bad guys who have taken over the planet.

He learns that the original advance colonization team has almost all died from this mysterious plague. It seems that a scheme is afoot to take over this brand new planet by killing off the rightful owners with the plague, while the new colonists will be immunized. Calhoun must first discover the nature of the plague and why it was so difficult to diagnose (the answer seems reasonably clever though I am not a doctor), and then safely dislodge the bad guys from the planet, in such a way as to discourage their soon arriving large group of colonists from trying to finish the job. The novel version adds some extended stuff about the motivation and character of the evil genius who devised the plague.

It's not a great story, but it's OK. As I say above, I think it's better suited to a length of around 20,000 words than to the longer Ace Double length.

William F. Jenkins (better known in the SF field as Murray Leinster) was born on June 16, 1896, and died in 1975, just short of his 79th birthday. He was an extremely respected SF writer, known as the Dean of Science Fiction, and a Hugo winner. He wrote successfully in many other fields, and was also the inventor of the front projection process used in creating special effects. In honor of his birthday, I am reposting this review of one of his best known novels, backed with a less well known novel.

The longer and better known of these novels, The Pirates of Zan, was first published in Astounding, February through April, 1959, under the title "The Pirates of Ersatz". The cover of the February issue is perhaps one of the more famous Astounding covers. It's by Kelly Freas and shows a space pirate with a slide rule instead of a dagger in his teeth.

|

| (Cover by Kelly Freas) |

|

| (Cover by Dean Ellis?) |

"Med Service" the novella is about 22,000 words. The novel version (The Mutant Weapon) is quite a bit longer, at 34,000 words. It adds a couple of chapters at the end, going into much more detail about the motivations of the chief villain of the piece. I thought the story better at the shorter length.

|

| (Covers by ? and Ed Emshwiller) |

The Pirates of Zan is really fairly minor stuff. It seems intended to be humourous, and it is much of the time, though some is just crank-turning. Our hero is a native of a pirate planet, but he wants to live an ordinary life, so he travels to a rich, settled, planet and sets up as a EE. But when his radical brilliant new power plant design is rejected, and he ends up accused of murder (for weird reasons that never make sense), he finds himself on the run. He ends up on a backward planet, and once again runs afoul of the local customs, after rescuing a beautiful girl from an abduction attempt. Upon escaping, he kidnaps a few of the locals and sets up as a pirate, but a completely non-violent one. He works an unconvincing scheme to use the threat of piracy to manipulate shipping and insurance stocks so that he can make enough money to a) pay off the locals who have become his crew, b) repay the people he pirated, c) set up a defrauded group of colonists on a new planet, and d) get rich enough himself to marry his girl back on the first planet he went to. Of course, he succeeds wildly, except for coming to realize that his ersatz piracy is vital to civilization, both for economic reasons and for romantic reasons, so he's stuck being a pirate, and also except for realizing (big surprise!) that his first girl is a boring spoiled brat but that he really loves the girl he rescued on his second planet. It's rather rambling, and it really doesn't convince, but it does pass the time pleasantly. It should be noted that it was nominated for the Best Novel Hugo.

The Mutant Weapon is probably intended a bit more seriously. The Med Service man Calhoun, hero of the overall series of Med Service stories, comes to a planet which is about ready for full colonization, intending to give it a basic inspection. It seems that the Med Service is the main organization keeping civilization together -- the Galaxy is too big, travel times too great, for a true interstellar government. When he arrives he is shocked to be attacked (by manipulation of the spaceship landing grid). He manages to escape and land in an isolated area. He and his alien pet/testbed Murgatroyd make their way towards the main city. He discovers a man who seems to have died from starvation, amidst what seems to be plenty of food. He is attacked by a nearly starving young woman, but convinces her he's not from the bad guys who have taken over the planet.

He learns that the original advance colonization team has almost all died from this mysterious plague. It seems that a scheme is afoot to take over this brand new planet by killing off the rightful owners with the plague, while the new colonists will be immunized. Calhoun must first discover the nature of the plague and why it was so difficult to diagnose (the answer seems reasonably clever though I am not a doctor), and then safely dislodge the bad guys from the planet, in such a way as to discourage their soon arriving large group of colonists from trying to finish the job. The novel version adds some extended stuff about the motivation and character of the evil genius who devised the plague.

It's not a great story, but it's OK. As I say above, I think it's better suited to a length of around 20,000 words than to the longer Ace Double length.

Thursday, June 14, 2018

Old Bestseller Review: Invitation to Live, by Lloyd C. Douglas

Old Bestseller Review: Invitation to Live, by Lloyd C. Douglas

a review by Rich Horton

Lloyd C. Douglas was indisputably one of the bestselling authors of the 20th Century. His best-known novel, The Robe (1942), was, according to Publishers' Weekly, the bestselling novel of 1943, and also of 1953 (the year in which the film, starring Richard Burton, was released); and it was also the 7th bestselling novel of 1942, and the second bestselling novel of both 1944 and 1945. The Big Fisherman, a loose sequel to The Robe, and Douglas' last novel, was the bestselling novel of 1948, and Green Light was the bestselling novel of 1935. His novels Disputed Passage, White Banners, Forgive Us Our Trespasses, and Magnificent Obsession (his first novel) also appeared on the PW lists of the top ten bestselling novels of the year. (The novel at hand, Invitation to Live, did not!)

Lloyd Cassel Douglas was born in Indiana in 1877 as Doya C. Douglas. (I don't know when or why he changed his name.) His father was a Lutheran Minister, and like many PKs (preacher's kids) he moved around a fair amount as a child. He was himself ordained a Minister in 1903, and served as a Pastor of Lutheran churches and later Congregational churches in a variety of places (including at the University of Illinois, my own alma mater), making his way to Los Angeles and finally to Montreal (which means he qualifies as a Canadian writer! Yay, more Canlit!) In 1927 he retired from the pulpit to write. He died in 1951, having published nine novels, a memoir, and a book derived from a journal mentioned in Magnificent Obsession. Besides The Robe, at least three other novels (White Banners, Magnificent Obsession (twice), and The Big Fisherman) became movies. For all this success, he seems largely forgotten these days, though at least The Robe and Magnificent Obsession (perhaps aided by the films) do seem to have some remaining reputation.

Douglas was a very distinctly Christian writer, didactically so. Invitation to Live is certainly an example. It was published in 1940. My edition is a wartime reprint from Grosset and Dunlap, complete with notice assuring us that while it is published in accordance with regulations to conserve paper it is complete and unabridged.

Douglas was a very distinctly Christian writer, didactically so. Invitation to Live is certainly an example. It was published in 1940. My edition is a wartime reprint from Grosset and Dunlap, complete with notice assuring us that while it is published in accordance with regulations to conserve paper it is complete and unabridged.

The novel opens with Barbara Breckenridge, just about to graduate from college, receiving a generous legacy from her grandmother, with one stipulation -- that she attend Trinity Cathedral, in Chicago (she lives in New York), the weekend after her graduation, alone. Barbara, a bit uncertainly, does so, and is particularly impressed with the sermon, given by Dean Harcourt, the wheelchair-bound pastor. She feels compelled to meet with the Dean, and ends up discussing her fears that no one really knows her or likes her -- they are all friendly to her only because of her money. The Dean ends up suggesting that the money is a handicap, and that she head somewhere dressed unmodishly, find work, and see if she can make real friends. And Barbara decides to do so, and ends up at a department store, buying cheap clothes from a brassy young woman. Somehow they click, and when Barbara notes the other woman, Sally's, remarkable ability as a mimic, she suggests that Sally take her place doing summer stock in Provincetown. And indeed, so it goes -- Barbara heads west and ends up on a farm in Nebraska, and Sally goes to Provincetown where she is (rather implausibly) almost immediately discovered by a Hollywood agent and whisked off to make a film.

Suddenly the novel shifts gears, and we meet Lee Richardson, working at his Uncle's bank in Southern California. We gather immediately that he hates banking -- he wants to be an artist -- and he also hates his bossy Aunt's plans for his life, which include taking over the bank, and marrying the suitable yet boring young woman she has chosen for him. He is presented with an unexpected opportunity to escape when a flood washes out the bridge his car is crossing, and he barely survives. Letting his family assume he is dead, he takes another name and ends up in Chicago, learning to be an artist. But, somewhat discontented, he too ends up at Dean Harcourt's church -- and the Dean sends him to Barbara's farm in Nebraska, telling him to paint pictures of farm life. When he meets Barbara, we aren't surprised that sparks fly ...

And the novel moves on to Sally, in Hollywood, as she makes a successful film -- and also makes enemies with her selfish and spendthrift behavior. Sally too, it is clear, needs the Dean's help to set her moral life on a better path. But the Dean thinks Sally is Barbara's responsibility ... and this all ends up enmeshing Lee (now called Larry) in the whole thing. And the next chapter introduces yet another character -- Katherine, a regular attendee of the Dean's church, who is wasting her life by letting her family oppress her. In particular, when she meets a promising young man, her lazy but pretty sister immediately jumps in ... So the Dean involves her as well in the lives of Barbara and Lee/Larry and Sally ...

Well, the overall arc is fairly clear -- the Dean's ways will eventually set everyone's lives on better, Christian, paths. (His Christianity, I should note, is a very mainline Protestant, works-based, theologically thin, sort.) The Dean has assembled quite a stable of acolytes, people he has helped over the years, and Barbara, Lee, Sally, and Katherine are primed to join this stable.

It's all fairly obviously didactic and a bit moralistic; and fairly implausible in its working out. Even so, I enjoyed long stretches of it. The characters are certainly no more than two-dimensional, but their struggles do engage the readers' interest. The plot twists and turns may be sort of obvious, but they are still intriguing. The romance of Barbara and Lee/Larry is worth rooting for. Unfortunately, Douglas seemed to lose interest once he had the ending all arranged, and the book just kind of peters out in the last chapter. Certainly this is far from a great book -- and indeed it's easy to see why this was one of the few Douglas books not to become a major bestseller -- but it's tolerably entertaining for its relatively short length.

a review by Rich Horton

Lloyd C. Douglas was indisputably one of the bestselling authors of the 20th Century. His best-known novel, The Robe (1942), was, according to Publishers' Weekly, the bestselling novel of 1943, and also of 1953 (the year in which the film, starring Richard Burton, was released); and it was also the 7th bestselling novel of 1942, and the second bestselling novel of both 1944 and 1945. The Big Fisherman, a loose sequel to The Robe, and Douglas' last novel, was the bestselling novel of 1948, and Green Light was the bestselling novel of 1935. His novels Disputed Passage, White Banners, Forgive Us Our Trespasses, and Magnificent Obsession (his first novel) also appeared on the PW lists of the top ten bestselling novels of the year. (The novel at hand, Invitation to Live, did not!)

Lloyd Cassel Douglas was born in Indiana in 1877 as Doya C. Douglas. (I don't know when or why he changed his name.) His father was a Lutheran Minister, and like many PKs (preacher's kids) he moved around a fair amount as a child. He was himself ordained a Minister in 1903, and served as a Pastor of Lutheran churches and later Congregational churches in a variety of places (including at the University of Illinois, my own alma mater), making his way to Los Angeles and finally to Montreal (which means he qualifies as a Canadian writer! Yay, more Canlit!) In 1927 he retired from the pulpit to write. He died in 1951, having published nine novels, a memoir, and a book derived from a journal mentioned in Magnificent Obsession. Besides The Robe, at least three other novels (White Banners, Magnificent Obsession (twice), and The Big Fisherman) became movies. For all this success, he seems largely forgotten these days, though at least The Robe and Magnificent Obsession (perhaps aided by the films) do seem to have some remaining reputation.

Douglas was a very distinctly Christian writer, didactically so. Invitation to Live is certainly an example. It was published in 1940. My edition is a wartime reprint from Grosset and Dunlap, complete with notice assuring us that while it is published in accordance with regulations to conserve paper it is complete and unabridged.

Douglas was a very distinctly Christian writer, didactically so. Invitation to Live is certainly an example. It was published in 1940. My edition is a wartime reprint from Grosset and Dunlap, complete with notice assuring us that while it is published in accordance with regulations to conserve paper it is complete and unabridged.The novel opens with Barbara Breckenridge, just about to graduate from college, receiving a generous legacy from her grandmother, with one stipulation -- that she attend Trinity Cathedral, in Chicago (she lives in New York), the weekend after her graduation, alone. Barbara, a bit uncertainly, does so, and is particularly impressed with the sermon, given by Dean Harcourt, the wheelchair-bound pastor. She feels compelled to meet with the Dean, and ends up discussing her fears that no one really knows her or likes her -- they are all friendly to her only because of her money. The Dean ends up suggesting that the money is a handicap, and that she head somewhere dressed unmodishly, find work, and see if she can make real friends. And Barbara decides to do so, and ends up at a department store, buying cheap clothes from a brassy young woman. Somehow they click, and when Barbara notes the other woman, Sally's, remarkable ability as a mimic, she suggests that Sally take her place doing summer stock in Provincetown. And indeed, so it goes -- Barbara heads west and ends up on a farm in Nebraska, and Sally goes to Provincetown where she is (rather implausibly) almost immediately discovered by a Hollywood agent and whisked off to make a film.

Suddenly the novel shifts gears, and we meet Lee Richardson, working at his Uncle's bank in Southern California. We gather immediately that he hates banking -- he wants to be an artist -- and he also hates his bossy Aunt's plans for his life, which include taking over the bank, and marrying the suitable yet boring young woman she has chosen for him. He is presented with an unexpected opportunity to escape when a flood washes out the bridge his car is crossing, and he barely survives. Letting his family assume he is dead, he takes another name and ends up in Chicago, learning to be an artist. But, somewhat discontented, he too ends up at Dean Harcourt's church -- and the Dean sends him to Barbara's farm in Nebraska, telling him to paint pictures of farm life. When he meets Barbara, we aren't surprised that sparks fly ...

And the novel moves on to Sally, in Hollywood, as she makes a successful film -- and also makes enemies with her selfish and spendthrift behavior. Sally too, it is clear, needs the Dean's help to set her moral life on a better path. But the Dean thinks Sally is Barbara's responsibility ... and this all ends up enmeshing Lee (now called Larry) in the whole thing. And the next chapter introduces yet another character -- Katherine, a regular attendee of the Dean's church, who is wasting her life by letting her family oppress her. In particular, when she meets a promising young man, her lazy but pretty sister immediately jumps in ... So the Dean involves her as well in the lives of Barbara and Lee/Larry and Sally ...

Well, the overall arc is fairly clear -- the Dean's ways will eventually set everyone's lives on better, Christian, paths. (His Christianity, I should note, is a very mainline Protestant, works-based, theologically thin, sort.) The Dean has assembled quite a stable of acolytes, people he has helped over the years, and Barbara, Lee, Sally, and Katherine are primed to join this stable.

It's all fairly obviously didactic and a bit moralistic; and fairly implausible in its working out. Even so, I enjoyed long stretches of it. The characters are certainly no more than two-dimensional, but their struggles do engage the readers' interest. The plot twists and turns may be sort of obvious, but they are still intriguing. The romance of Barbara and Lee/Larry is worth rooting for. Unfortunately, Douglas seemed to lose interest once he had the ending all arranged, and the book just kind of peters out in the last chapter. Certainly this is far from a great book -- and indeed it's easy to see why this was one of the few Douglas books not to become a major bestseller -- but it's tolerably entertaining for its relatively short length.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)