|

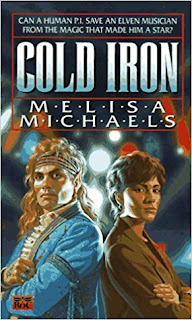

| (Covers by Ed Emshwiller) |

To repeat what I wrote in an earlier post about Bradley: Marion Zimmer was born in 1930 in Albany, NY. She was a very active SF fan from the late '40s, and she published several fanzines as well as numerous exuberant letters in the letter columns of the pulps of the day (I have several issues of old magazines with her letters). She married Robert Bradley in 1949, and they had one son, David, who became a writer, and died in 2008. (MZB's brother, Paul Zimmer, was also an active fan whose letters are easy to find in old SF magazine lettercols, and who later became a reasonably accomplished writer.)

The Bradleys divorced in 1964, and Marion married Walter Breen, a fellow SF fan and a noted numismatist, within a month. Breen was already well known as an advocate of pederasty, and MZB certainly knew of his proclivities, and indeed Breen had been banned from at least one SF convention in that time period. Breen had been convicted of pederasty-related crimes as early as 1954, and continued to have trouble with the law, finally going to jail after another conviction in 1990. MZB managed to dodge serious consequences of her husband's activities throughout her life, and she died in 1999. In 2014 her daughter, by Breen, Moira Greyland, accused her of sexual abuse, and in retrospect it seems to me that it should have been clear all along that Bradley was at least negligently complicit in her husband's crimes, certainly aware of them, and now it appears more likely than not that she was a participant herself.

My view of the treatment of art produced by people later shown to be morally compromised or worse is straightforward -- the art is not affected (though it's fair game to view it with an eye to how the creator's apparent attitudes inform it), and while I support the notion of trying to avoid direct benefit to criminal creators, I absolutely reject the notion of censoring art by "bad" people. Bradley, it seems to me, represents a curious test case here -- because her work, in my view, though at times quite enjoyable, was never truly outstanding. Indeed, a novel like The Mists of Avalon, to my mind, received excessive praise when it appeared for essentially political reasons, making it ironic that it may now be suppressed by some for still political reasons. All that said, even it it is true that the world wouldn't miss Bradley's work all that much were it forgotten, I think it should be remembered for exactly what it is.

The Door Through Space opens with Race Cargill, a Terran who has spent most of his life on the planet Wolf, preparing to leave for a post on another world. He is a member of the Terran Secret Service, chained to a desk for the past six years after a confrontation with his friend and brother-in-law Rakhal which led to a blood feud between them. It seems that Rakhal, a human native of Wolf, had been working for the Secret Service but had turned renegade, and now supported independence for the planet. Race knows if he leaves the Terran areas he will have to fight Rakhal -- and either he will die himself or he will kill his sister's husband. So after years behind a desk he has decided to leave.

But at the last moment he is called back to investigate one more problem. Rakhal has disappeared and taken his daughter, and Race's sister Juli is begging for help. At the same time there is native unrest, and there are rumors of a matter transmitter being used somewhere on the planet. Terra really wants the matter transmitter!

So Race goes native again, and begins a journey to the Dry Towns to seek out Rakhal. At the same time he is beguiled be visions of a beautiful woman who has appeared to him a couple of times only to suddenly disappear, at the temples of Nebran, the evil Toad God. Race's travels lead him to a Dry Town royal, the twin sister of his mysterious woman, and to an alien city, and to stories of strange toys with sinister effects. It all works out more or less as you might expect. Tolerable enough stuff in what I would call a sub-Leigh Brackett mode.

|

| (Cover by Enrich) |

Arthur Bertram Chandler (1912-1984) was an English-born Australian seaman who began writing SF for Astounding in the 40s. His most famous stories are about Commodore John Grimes, a spaceship Captain in the Rim Worlds of our Galaxy. Chandler's spaceships, not surprisingly, recall sea ships a lot, particularly in the command organization.

|

| (Cover by John Schoenherr) |

There the foursome are kidnapped, and they soon realize that they are held by an exiled AI. This seems to be a sort of Williamsonian robot, obsessed with making humans happy and safe, to a fault. The AI wants to keep the foursome forever, and goes so far as to create beautiful android women for them.

The do escape, of course, but not without cost. Indeed, the novel's ending is quite dark. The thing as a whole is a bit of an implausible mess, but to a small extent it is redeemed by the unexpectedly bitter conclusion.