Convention and Vacation Report, Sasquan 2015

by Rich Horton

Part IV: Saturday (and the Hugos) and Sunday

Saturday morning we figured we'd get a real breakfast. My preference is to find a good local place, instead of a chain. So while there was a Perkins near the hotel (which would have been fine), we used the smartphone to find a place called Waffles Plus. It was a bit of dive decor-wise, but the service was fast and the food was fine. Then we went back to the convention. First stop of course was the business meeting. There were to be preliminary presentations on the major proposal (EPH, 4/6), and an attempt to clear out the rest of the business. Again I couldn't stay long but Mary Ann stayed for most of it. The proposal to eliminated the 5% requirement to get on the ballot, a longtime bugaboo of mine, did pass, fairly easily. I can't remember the order of actions, but for the most part discussion of EPH and 4/6 was put off until Sunday. I should mention that the Site Selection winner for 2017 was announced (most people had heard this the night before): Helsinki, Finland; a very popular choice. (I'm happy with it winning, though I will almost certainly not be able to afford to attend.)

I had signed up for James van Pelt's Kaffee Klatche, at 10, so I rushed out pretty quick to make it. James (as mentioned) has been a long-time friend online, from SFF.net days and such, and it was a privilege to watch his career develop (and reprint some of his best work). He has a new YA novel out from Fairwood Press,

Pandora's Gun. There was a nice group there, and a lot of what James discussed was working writer stuff: how long it takes him to write a story, the marketing process. James has over time (sometimes a long time!) sold a remarkable percentage of his stories. I spent a certain amount of time (perhaps too much, but they asked!) talking about things from the reviewers' side, the state of the market and so on. A good talk.

Next up for me, at 12, was the panel "How to Edit Anthologies", with John Joseph Adams, Ellen Datlow, and Mike Resnick. I've done this panel a few times before at various cons, and so too I know have John, Ellen, and Mike. I admit to feeling a bit tired of the whole concept and not really looking forward to it much, but the panel actually went quite nicely. I've been on panels with all of these folks before, and by now I know them all fairly well (Mike Resnick perhaps a bit less well, but I've talked with him at length too -- or should I say mostly listened -- he's an excellent storyteller, in person as well as in print). I don't know if that helps on a panel -- I think maybe it does, though I'm always excited to meet new people too. We discussed the usual things: story order, open vs. closed anthologies, reprint vs. original, etc. Not sure we broke any new ground, but as I said it seemed to go well.

I seemed to be in a rush, and the next panel I was interested was "The Future of Online Magazines", but between running into people for a chat etc. I got there pretty late. The panelists were Anaea Lay (

Strange Horizons), Scott Andrews (

Beneath Ceaseless Skies), John Joseph Adams (

Lightspeed, of course), Mike Resnick (the late lamented

Baen's Universe), and Neil Clarke (

Clarkesworld). So, a good, representative set. I was happy to meet Anaea and Scott, neither of whom I had yet run into.

My next panel was at 3:00, so I figured I'd run over to the Hugo Ceremony rehearsal, which ran from 2 to 4 -- it was advertised as just taking 5 or 10 minutes for a quick runthrough. Alas, to begin with the theatre space they were using (the INB) was locked, and finally someone found us (about 10 or 15 people had shown up) and took us in a back door. Things were a bit disorganized -- I think the director and the presenters (David Gerrold and Tananarive Due) had expected this time to be mainly for their rehearsal. David gave us a nice talk, about how to walk on the stage and all that, and what to expect. (There was some distinct tension noticeable, to do with worrying about the possibility of boos, and No Awards, etc.) It ended up taking nearly the whole hour -- indeed, I ducked out a bit in advance of any actual practice (unnecessary anyway, I think) in order to make the Space Opera panel at 3.

This was in a room I hadn't been in before, not as large as some of the others, and the room was absolutely packed. The front table was tiny, so the five had to rather squeeze in and around it. I joked "biggest crowd and smallest front table at the con". The five panelists were me as moderator (on the strength of my

Space Opera anthology, I suppose) with four writers who have definitely done Space Opera: Doug Farren, Jeffrey Carver, Charles Stross, and Ann Leckie. Being a moderator is not necessarily as easy as it might seem, though my fellow panelists were certainly helpful. In all, I think the panel went well. We discussed the history of Space Opera, of the so-called "New Space Opera", Bob Tucker's invention of the term, the revitalization of it by the likes of, in different ways, Brian Aldiss, Samuel R. Delany, and M. John Harrison ... followed of course by Banks and co. Also the experiences of each of the authors writing Space Opera ... often without really considering what they were doing Space Opera at the time.

Then it was back to the hotel room to relax a bit and then change for the Pre-Hugo Reception. The reception (for the nominees, presenters, and guests) featured drinks and appetizers -- a pretty nice spread. They dragged us off for pictures during the process. We ran into a number of people, of course -- I was able to introduce Mary Ann to Ann Leckie, who was there with her high school age son. We had a nice conversation about Webster Groves schools -- as our kids and Ann's all went to Webster Groves High School, and Mary Ann worked at the grade school where Ann's kids went (though she left there for another job in the district before Ann's kids would have been in the class she worked at).

I also got to talk to Brent Bowen, a friend of some years (from the KC area), who was a Hugo nominee for his fine podcast

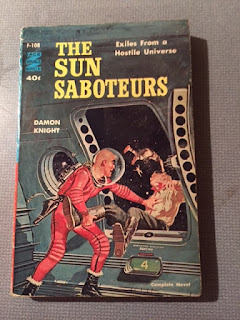

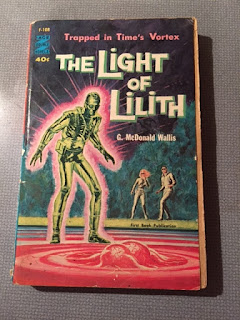

Adventures in Sci-Fi Publishing. He had just got in town after first seeing a long-planned concert by the Foo Fighters. This is also when I asked Robert Silverberg to sign the Ace Double I had bought. Talked some as well with Neil Clarke and Sean Wallace. And other people too, but one of the problems with waiting so long to write all this up is that I forget things. (That's probably one of the problems with being 55, too.)

At just about 8 we were escorted to the INB for the ceremony. We had assigned seating, in part to keep the nominees close to the stage for easy access should we win. The

Lightspeed crew were seated in something like the sixth row. John Scalzi was just a few seats to my left. Naturally I started to get a bit nervous.

The ceremony took a while to get going -- they showed the "Pre-Hugo" show being streamed at Ustream (which would stream the ceremony), and the folks on the show made some broad comments about how much stretching they were having to do. David Gerrold and Tananarive Due did a really nice job throughout the ceremony. It opened with a bit of Star Trek schtick, amusing enough. Robert Silverberg came up and performed a special "Blessing of the Hugo", based, he said, on encounters with the Hare Krishna at a long ago Worldcon. The entire audience sang along to the Hare Krishna chant. Connie Willis also gave an amusing talk. Alas, I have already forgotten her jokes ... It's that 55 thing again.

The awards part of the ceremony began with a series of non-Hugo awards. A special award was presented to the late Jay Lake, a Northwest-based writer who died of cancer in 2014. Jay was a super writer, and a really good man. He was special to a lot of people, and for me to to claim to be close to him would be wrong, but I always felt close, because we were both writing for

Tangent at the same time, back in the late '90s, and we corresponded a fair bit. Because of the

Tangent connection, I followed his rapidly burgeoning career closely, and I was delighted as he progressed from a very prolific, and always interesting, writer of short stories for mostly small 'zines to a Hugo-nominated writer to a Campbell winner to a prolific novelist. I was thrilled to be able to reprint some of his stories. I finally met Jay at Chicon in 2012, when he was in remission from his cancer. The award was accepted by his sister, and it seemed totally appropriate to me.

The First Fandom award went to Julian May, who was born in 1931, and was active in fanzines in the late '40s. Her first SF story was the excellent novella "Dune Roller", which appeared in 1951 in

Astounding, but after only one more story she left the field. She married the anthologist T. E. Dikty, editor of the first Best of the Year series. She kept writing in ensuing years, including a series of juveniles, and later some media tie-in sort of work as by "Ian Thorne". She returned to the field in 1981 with

The Many-Colored Land, which made a huge splash, and since then has published quite a few further novels. She's still alive, but was unable to attend the convention.

The Sam Moskowitz award went to David Aronowitz, a collector and bookseller.

And the Big Heart award went to Ben Yalow. I was thrilled by this award as well. Ben is a SMOF, of course, and a very nice guy. I've known him for quite a while, though not all that closely, but we've talked on a number of occasions at smaller cons. The first time I met him I remember asking if he was related to Rosalyn Yalow, who won the Nobel Prize in 1977, while I was a student at the University of Illinois, where she got her Ph.D. (so naturally they made a big deal of her). Ben, of course, is Rosalyn's son. A very deserving winner.

The final "non-Hugo" is an award that lots of people, I suspect, think of as a Hugo, because it is nominated and voted for in the same process: the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. The winner was Wesley Chu, a very deserving winner as well. He won from a shortlist otherwise dominated by "Puppy" nominees, and No Award finished second, a bellwether for the Hugos, no doubt. That said, I think Chu was a likely winner against any field of nominees, though Andy Weir, author of The Martian and the first person left off the ballot, might have given him a run for his money. (The next writer on the long list of people just short of a nomination who really would have excited me was Sam J. Miller, who wouldn't have made the ballot regardless of the slates ... which is not to say that the writers ahead of him are at all unworthy.)

So, it was finally time for the Hugos. I won't post the whole list, because it's readily available. Most notable acceptance speech was by James Bacon, one of the winners for Best Fanzine (

Journey Planet), though perhaps I give him extra credit for his Irish accent. (One of his fellow-editors at

Journey Planet, Chris Garcia, is famous for one of the best Hugo acceptance speeches of all time after he won for another fanzine (

The Drink Tank) in 2011 -- indeed, James gave a good portion of that speech (which was actually nominated for Best Dramatic Presentation (Short Form) the following year.) I would say that from my perspective the choices for the Hugo were good choices, not always what I voted for but worthy work in context.

Jumping around a bit, I'll add that the most funny part of the ceremony was the Dalek that presented the Dramatic Presentation awards. Great fun. There were, of course, moments of great controversy. The first involved the now notorious asterisks. These are little wood coaster sized things that were sold (in slightly smaller versions) to benefit one of Sir Terry Pratchett's favorite charities, The Orangutan Foundation. The full-sized versions were given to all the Hugo nominees. Of course it was a joke suggesting that there might be an asterisk associated with the awards this year -- which one would have to be a dolt not to have noticed. I believe it was intended as a light-hearted, affectionate joke, and it should have been taken that way, but many people weren't ready (may never be ready) to accept that. Gerrold gave a presentation saying that the six arms of the asterisk were exclamation points -- celebrating the many records Sasquan set, such as most Hugo voters.

The other major controversy occurred in the categories where No Award won. In each case, there was a lot of cheering, which I thought regrettable. No Award was probably appropriate in most of these cases, certainly understandable as a rebuke to the slate tactic, but it was nothing to celebrate. As it happens, I chose not to vote No Award first myself in any category, but that said, I felt the nominations in each case were tainted by the slate support, and the overall shortlists much much weaker than usual. Except for the editor categories, I did not feel I was voting for candidates that were truly Hugo-worthy -- I was voting for solid and enjoyable stories that I didn't feel would besmirch the Hugos.

Anyway ... (as Washington native Joel McHale might say) ...

The cool part -- for me! The award for Best Semiprozine was presented by TAFF (Transatlantic Fan Fund) representative Nina Horvath, from Austria. (One of several she presented.) She read the name of the category as "Seamy Prozine", which (as David Gerrold noted) seemed a nice way to put it! I will confess now that while I had tried to tell myself all along that we had at best a 1/3 chance of winning, I was actually kind of confident, on two grounds: we won last year, and the (limited) set of posted ballots seemed to favor us. Oh, and I think we're pretty deserving! (Which is not to say that the other nominees,

Strange Horizons,

Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Abyss and Apex, and

Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine aren't outstanding as well.)

So anyway, as the announcement came -- well, I was thrilled, that's all I can say. The five of us went up, and got like three Hugos to share on stage (the other two we got backstage, and sorted them out according to nameplate.) We all got to talk for about a minute and a half. I don't think I quite made a fool of myself, but I was a bit stiff. One thing that a lot of people noted from previous ceremonies is absolutely true -- you cannot see the audience at all from the podium.

We went back to our seats, and saw the rest of the award presentations. Then we hung around for a while for official photographs, taken on stage. The photographer, the excellent John O'Halloran, herded us cats into place, and took his pictures, then audience members were allowed to take their own.

Then it was time for the afterparties. We went first to the traditional Hugo Losers' Party, which this year was just called the Post-Hugo Reception or something like that, at Auntie's Bookstore in downtown Spokane. As usual, this was hosted by next year's Worldcon (in Kansas City, and thus run by a number of friends of mine). The gift was barbecue tongs. There was a nice crowd, and drinks, and some food. I talked to several people, including new F&SF editor, and first-rate writer, C. C. Finlay; the lovely Wang Yao, who writes as Xia Jia, and whose work I have reprinted; and Ken Burnside, a nominee for Best Related Work whose "The Hot Equations" was broadly regarded as the best of the nominees, and which indeed did finish second (to No Award). We talked at some length -- Ken was sensible, a bit upset about the way the Puppies were treated but somewhat understanding as well, and quite convinced that things are only going to get worse for the Hugos.

I had heard that George R. R. Martin (who, with Gardner Dozois, started the Hugo Losers' Party tradition back in the '70s) was hosting a Losers' Party somewhere, but I didn't get an invitation. (Possibly because I wasn't a Hugo Loser, who knows?) It sounds like it was a good time. As far as I know, none of the

Lightspeed crew made it there, though I know he was trying to find John Joseph Adams, who did qualify as a Hugo Loser because he was one of those knocked off the ballot (in Editor, Short Form) by the slate candidates. As it was I stayed for a while at Auntie's, hoping to link up with the rest of the crew, but only saw Stefan Rudnicki, our Podcast Editor.

Mary Ann was getting a bit tired, so we went back to the hotel, then I went out again (on foot and by bus), and first made my way to the SFWA Suite. It was fairly empty, but I was fortunate to strike up a long conversation with Brian Dolton, a fine writer (we've actually shared a TOC, in the Spring 2011

Black Gate), who was serving the Scotch. So we talked about Scotch, and about Iain Banks (who was an expert (of the "fan" sort) on Scotch, wrote a book about it), and about Thorne Smith, and about Roger Zelazny.

After some time in the suite, I went down to the bar on the first floor. There was a nice crowd there as well. I spent some time talking to the fine writer Alvaro Zinos-Amaro, who is one of those I also know from a mailing list. The

Lightspeed crew also showed up, and was able to talk for some time to Christie and Wendy and John. Annie Bellet was there, showing off her Alfie, awarded by George R. R. Martin at his party. I am distressed that I am forgetting some of the other folks I talked with -- partly because it's late, but also, alas, I took too long to get around to writing this. One of them (could it have been Ramez Naam, another fine young writer?) shared a drink with me after the bar closed. Anyway, I had a great time -- lots of great conversation, the key (in my opinion) to any con.

(Not that winning a Hugo didn't help!)

It was about 4, as I recall, that I went back to the hotel.

So then Sunday, time for the trip home. But first, back to the con for one more panel, and another swoop through things. We did first go to the Business Meeting again, where the two major Hugo Reform proposals were considered, EPH and 4/6. Both passed, EPH by a wide margin, 4/6 on a very close vote. That was preceeded by a series of votes aimed at selecting which variant of 4/6 would be the official one (5/10, 5/8, etc.) My suggestion was 5/10, but I would have been happy with 5/8, which alleviated one problem with 5/10 (a perhaps too long short list). 5/8 failed without a count, on the chair's ruling. I will be honest and say that I thought it was too close to rule it out without a count, but I wasn't quick enough (or brave enough) to ask for a count. I will add that I strongly believe 5/8 a far better option. I should note (as was noted at the meeting) that EPH and 4/6 (or its variants) are not mutually exclusive. I will also add that I actually got up and spoke (in favor of 4/6) at the meeting. I suppose you could see me on You Tube, if you wanted. (I haven't.)

There were a couple of 11 o'clock panels I had some interest in: Historical Fiction for SF Readers and The Role of the Critic. It was rather late when I left the Business Meeting, and I opted for The Role of the Critic, because it featured Liza Groen Trombi, editor of

Locus, and also Alvaro Zinos-Amaro (and Alan Stewart, whom I don't know, but who was a good panelist as well.) I only caught the last 15 minutes or so, then was able to say Hi to Liza.

That was about it -- we had a 3:00 flight to catch, and so figured we'd leave about 1:00. I did take the time to pick up a Hugo box, to run through the Dealers' Room one more time, and also to go by the Green Room. Then it was off to the airport.

I like small airports, and Spokane's qualifies. It was easy to navigate, and the lines were short. (I forgot to mention earlier that on leaving St. Louis the lines to check baggage were horrendous, and so I actually paid a skycap to do it for us.) Naturally TSA took great interest in the Hugo, but not terribly suspicious interest. They did unpack it, and rub it down to see if there was explosive residue. It may have helped that another con attendee was in line with me, and he eagerly told the agents what to expect.

The flight back was tolerable. I read most of the Silverberg Ace Double. Both planes were delayed, making us 4 for 4 on the trip. We got in well after midnight -- so it was a good thing I had planned all along to take Monday off.

Final analysis -- I had a wonderful time. The stopover in Seattle was very enjoyable (boat trip probably the best part). The trip up Crystal Mountain to view Mt. Rainier was neat. The convention was great (even accounting for the tension surrounding the Hugo controversy). Best restaurant: Steelhead Diner in Seattle. Best in Spokane: Central Food. I don't think I mentioned meeting Andy Porter before -- editor of

Algol (later

Starship), one of the very first fanzines (or really a semiprozine) that I ever bought, and a wonderful 'zine -- also editor of

SF Chronicle, and a Hugo winner and Big Heart winner. Lots of other folks met, hopefully not too many forgotten in this report!

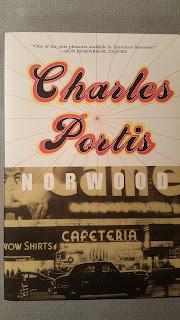

This blog is aimed first at books from, let's say, at least a half-century ago which were bestsellers, and also, sometimes, at books that have been "neglected" or "forgotten". I remember mentioning somewhere that one of the writers who is sometimes called "neglected" is Charles Portis, when he really isn't. In fact, for a writer with only five novels to his credit, the last of them published almost a quarter-century ago, Portis gets a pretty fair share of attention. To be sure, that's mostly because of one book -- True Grit -- and the two (both excellent) movies made from it. And the likes of Roy Blount, Jr. and Ron Rosenbaum did yeoman work, back in the day, to keep Portis in people's minds when few people remembered anything but the John Wayne movie. All that said, by now, all five of his novels are in print (from Overlook Press), and he is certainly on the general literary radar. (Which makes it a bit of a shame that he seems to be retired ... I don't know of anything new he's done this millennium, actually.)

This blog is aimed first at books from, let's say, at least a half-century ago which were bestsellers, and also, sometimes, at books that have been "neglected" or "forgotten". I remember mentioning somewhere that one of the writers who is sometimes called "neglected" is Charles Portis, when he really isn't. In fact, for a writer with only five novels to his credit, the last of them published almost a quarter-century ago, Portis gets a pretty fair share of attention. To be sure, that's mostly because of one book -- True Grit -- and the two (both excellent) movies made from it. And the likes of Roy Blount, Jr. and Ron Rosenbaum did yeoman work, back in the day, to keep Portis in people's minds when few people remembered anything but the John Wayne movie. All that said, by now, all five of his novels are in print (from Overlook Press), and he is certainly on the general literary radar. (Which makes it a bit of a shame that he seems to be retired ... I don't know of anything new he's done this millennium, actually.)