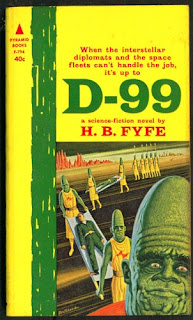

A Forgotten SF Novel: D-99, by H. B. Fyfe

A review by Rich Horton

Horace Browne Fyfe (1918-1997) was an active SF writer from 1940 through 1967, with the bulk of his work appearing between 1947 and 1963. He appeared mostly in Astounding, though by the '60s often in Fred Pohl's magazines (Galaxy and If), and he appeared elsewhere as well, in places like Amazing, Fantastic, and Gamma. The similarity of his name to another writer named H. B. plus something to do with a flute-like instrument (H. Beam Piper), along with the fact that both writers appeared often in Astounding, at about the same time, led to some speculation that one name or the other was a pseudonym, which is not true. Indeed, rather than Piper, Fyfe reminds me more of another Astounding/Analog writer, Christopher Anvil (Harry Crosby), and indeed also of a similarly obscure member of John W. Campbell's stable, Everett B. Cole.

The novel at hand, D-99, was published in 1962 by Pyramid, in paperback. Fyfe's most famous stories might be the five concerning an organization called the Bureau of Special Trading, or more colloquially, the Bureau of Slick Tricks. These stories appeared in Astounding between 1948 and 1952. The ISFDB lists D-99, his only novel, as another Bureau of Slick Tricks story, but though there are some similarities of theme and tone, that's not correct.

D-99 is a special division of the Department of Interstellar Relations, so named because it is on the 99th floor of the Department's building. This novel depicts a single night in the Department's history. It's job is to find ways to rescue Terrans from alien prisons, or other alien predicaments. This night there are four planets on which Terrans are in trouble: Tridentia, where a man named Harris has been captured by an aquatic race; Greenhaven, a puritanical Terran colony where a woman reporter, Maria Ringstad, has been imprisoned for violating the planet's rather strict moral rules; Yoleen, where one Gerson has been imprisoned for no discernible reason; and Syssoka, where two spacemen, Taranto and Meyers, have crashlanded and thus offended the local species.

The main viewpoint character at D-99 is Willy Westervelt, a young man, a pretty new recruit. The others with him are his boss, Smith; the boss's chief assistant, Pete Parrish; the genius gadgeteer Bob Lydman, who was himself once confined in an alien prison; and three woman, a couple of secretaries and a switchboard operator: Simonetta, Beryl, and Pauline, and well as a couple other minor characters. Westervelt is infatuated with Beryl, a bottle blond, to the point of outrageous sexual harassment, but alas she is more interested in being harassed by Parrish. Simonetta is the girl he should be after -- she clearly likes him. That whole aspect of the book is wildly sexist, in a vaguely Mad Men-ish fashion.

In between trying to steal a kiss from Beryl, Willy, who has very little agency (nor talent, far as we can tell) witnesses the department's monitoring the situation on each of the above-mentioned planets. At least in the story as show, we see very little that D-99 actually does to solve the problems. In fact, probably in at attempt to be true to life, sort of, the book shows, of the five prisoners, three successful rescues, one failure, and one left hanging at the end of the night. In between the chapters set at D-99 we get chapters from the points of view of the various imprisoned Terrans -- these in many ways are the more interesting.

There is another, rather trivial, crisis for D-99 to deal with: a power failure has stopped the elevators from working, trapping them on the 99th floor. (Also, implausibly, the doors to the stairways are locked because, you see, electricity is needed to open them -- which is not how such doors work, precisely because of the possibility of a power failure.) This means the D-99 folks need to stay late at work, and eat dinners like reconstituted martinis.

Anyway, this is an awfully trivial piece of work, not as interesting as the Bureau of Slick Tricks stories, not really very interesting at all. It is further weakened by Willy Westervelt's ineffectiveness ... it's hard to root for him, or even to see why he was hired. The sexism is, I suppose, much of it's time, but it still grates. I've seen other Pyramid novels from this period that were similarly trivial -- they seem to have been desperate, almost, and perhaps in a case like this to have turned to a veteran writer of short fiction and asked for a novel, getting in response a padded, ill-structured, thing that may have been based on unfinished ideas for a few shorter pieces.

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Thursday, May 21, 2015

Old Bestsellers: The Lion's Share, by Octave Thanet

Old Bestsellers: The Lion's Share, by Octave Thanet

A review by Rich Horton

It's always neat to run across an old book by a writer I've never heard of, and to find that they have an interesting story. Octave Thanet was the pseudonym of Alice French (1850-1934), born in Massachusetts (granddaughter of a Governer of that state), but who lived from the age of 6 mostly in Iowa and Arkansas. She was apparently a Lesbian, living with Joan Crawford for 40 years, though that seems to not to have been accepted widely until more recently (one site I saw calls Crawford her "widowed friend", apparently true but not the whole story -- another reference suggests that Crawford's husband's death was "mysterious"). As usual, contemporary Lesbian critics seem to stretch rather to find "coded" themes in her stories -- perhaps that's true, but I confess I found nothing of the sort in The Lion's Share, which of course doesn't mean much beyond that she was writing what she thought might sell, and avoiding controversy. Thanet was a very popular writer for a time, particularly, it seems, in the 1890s. Her novel Expiation seems to get, forgive me, the "lion's share" of praise.

It's always neat to run across an old book by a writer I've never heard of, and to find that they have an interesting story. Octave Thanet was the pseudonym of Alice French (1850-1934), born in Massachusetts (granddaughter of a Governer of that state), but who lived from the age of 6 mostly in Iowa and Arkansas. She was apparently a Lesbian, living with Joan Crawford for 40 years, though that seems to not to have been accepted widely until more recently (one site I saw calls Crawford her "widowed friend", apparently true but not the whole story -- another reference suggests that Crawford's husband's death was "mysterious"). As usual, contemporary Lesbian critics seem to stretch rather to find "coded" themes in her stories -- perhaps that's true, but I confess I found nothing of the sort in The Lion's Share, which of course doesn't mean much beyond that she was writing what she thought might sell, and avoiding controversy. Thanet was a very popular writer for a time, particularly, it seems, in the 1890s. Her novel Expiation seems to get, forgive me, the "lion's share" of praise.Thanet's views, for the most part, for good and bad, were consistent with popular attitudes of the time, particularly in racial matters. The Lion's Share, noticeably, is full of absurdly racist depictions of Japanese characters (which is not to say they were regarded as bad -- in fact, by and large, they are portrayed as good people, but in the most patronizing fashion). Thanet was pro-Capitalist, and it's a bit amusing to see some critics regard that as more objectionable than her racism.

Thanet's primary reputation was as a "local color" writer -- apparently many of her stories were set in Iowa or Arkansas, and were highly regarded for capturing local landscapes, mores, and dialect. The Lion's Share is an exception to this, however. It was published in 1907, and it's set primarily in San Francisco, which ought to be a hint as to a major event in the story! The original publisher was Bobbs-Merrill. My edition might be a first, but there's a pasted in page on the inside cover that suggests it was distributed by something called the Tabard Inn Library -- basically, you paid $1.50 for lifetime membership, and a nickel a week to borrow a book. (There are fairly nice black and white illustrations by E. M. Ashe, as well.)

It opens with Colonel Rupert Winter, on furlough from the Philippines, visiting the son of a friend, at Harvard. He witnesses the aftermath of the suicide of a young man named Mercer, gathering that Mercer killed himself because the depression of 1903 had ruined his family, partly because of the unwise investments of his older brother Cary, whom he meets as well.

A few years later, Colonel Winter, now invalided out of the Army, is in Chicago boarding a train, to accompany his sister-in-law, the rather pompous Mrs. Melville Winter, and his much more interesting Aunt, Rebecca Winter, on a trip to San Francisco. He happens to overhear someone he recognizes as Cary Mercer, seemingly plotting something nasty. The Winter women are taking young Archie Winter with them, and of a sudden it seems kidnapping is a possibility. Also on the train is Edgar Keatchem, a leading Robber Baron of the time, it seems, whose machinations seem to have contributed to the failure of the Mercer steel mill ... and who now threatens the owner of the railroad on which they ride. Finally, we meet Janet Smith, a Southern woman of a certain age (not a debutante, but not too terribly old) -- she's acting as Rebecca Winter's companion, but Mrs. Melville Winter is convinced she's a nasty schemer.

Not without incident (a robbery attempt) they reach San Francisco. Colonel Winter is concerned on numerous grounds -- he finds himself strangely attracted to Janet Smith, but he suspects she may be somehow connected to the putative kidnappers. And indeed Archie is kidnapped, under very odd circumstances ... and in the end he seems to quite enjoy the experience. Cary Mercer is involved, at first snubbing Colonel Winter ... Other Harvard boys are also involved. Then there is an attempt on the life of Edgar Keatchem, who seemed to be at the center of the scheming.

It's all quite a tangle, and it comes to a head with a certain major historical event in San Francisco in 1906. Things of course sort themselves out quite neatly. All the supposed potential villains that we have met turn out to be basically all right (if perhaps in some cases temporarily misguided), with one mostly offstage individual the real bad guy. The course or true love runs straight. Mrs. Melville Winter is appropriately put in her place, while Aunt Rebecca is vindicated. And the Colonel's soldierly instincts are to be sure the most virtuous of all.

Hmmm ... all in all, a minor work but amusing for the most part. Predictable as popular fiction so often is, but entertaining too. Another writer who I'm glad enough to have sampled, but of whose work I don't feel any particular need to read anything more.

Thursday, May 14, 2015

Another not so old Non-Bestseller: The Walled Orchard, by Tom Holt

Another not so old Non-Bestseller: The Walled Orchard, by Tom Holt

A review by Rich Horton

Tom Holt recently made a fair amount of news when he outed himself as the man behind the "K. J. Parker" pseudonym. This was not exactly a major shock -- Holt was by far the name most commonly suggested as being behind the Parker name. There were those who though Parker might be a woman (a notion I always thought unlikely, not because of any sense that the writing was "ineluctably masculine", but because of the treatment of men, women, and their relationships in Parker's books). Others were thrown off by stunts like Holt's publishing an "interview" with "Parker" at Subterranean a few years ago.

Tom Holt recently made a fair amount of news when he outed himself as the man behind the "K. J. Parker" pseudonym. This was not exactly a major shock -- Holt was by far the name most commonly suggested as being behind the Parker name. There were those who though Parker might be a woman (a notion I always thought unlikely, not because of any sense that the writing was "ineluctably masculine", but because of the treatment of men, women, and their relationships in Parker's books). Others were thrown off by stunts like Holt's publishing an "interview" with "Parker" at Subterranean a few years ago.

As for me, in the December 2010 issue of Locus I wrote the following: "I had more pleasure reading K J. Parker’s Blue and Gold than just about anything I've read all year. It features a beautifully constructed plot, plenty of cynical jokes and even some worthwhile commentary on man as a political beast. The story is set in what seemed to me something of an alternate Rome or Byzantium, perhaps a bit like the Rome of Avram Davidson's Vergil stories or his Peregrine stories. It concerns one Saloninus, who opens the book by telling someone "In the morning I discovered the secret of changing base metal into gold. In the afternoon, I murdered my wife." Whether either or both or neither of these claims is true is much of what the story is about, as well as what to make of his relationship with his city’s ruler, Prince Phocas. This is an extremely funny story through and through. The humor, and some of the darkness behind it, reminded me a good deal of Tom Holt's masterpiece, The Walled Orchard, which is close to as high praise as I have in me." Obviously that put me in the Holt=Parker camp, and after that I stayed silent on the subject at request, in order to keep a confidence.

Blue and Gold was one of the first "K. J. Parker" stories I read, and I have read many since, including several novels, among them the Engineer Trilogy, possibly his most famous work. I like them all, for the voice, yes, and for the intricate plots, and for the intriguing details of ancient technology and politics, and for the neat magic systems (when magic is present, that is), and for the dark but not quite despairing view of human nature.

I daresay most readers know Tom Holt best for his humorous fantasies, which began appearing in 1987 with Expecting Someone Taller. These are very funny and clever, and I read them happily for a while, but they began to seem a bit samey-samey after the first few. Since then I've sampled a couple more, with modest but not tremendous enjoyment. Holt also wrote a couple of sequels to E. F. Benson's series of books about Lucia and Mrs. Mapp (which I have not read because I tried the first of Benson's Lucia novels and disliked it), and, famously and (to Holt) embarrassingly, a collection of poems published when he was 13. I am not sure that I would ever have thought that K. J. Parker and the Tom Holt of the humorous fantasies were the same writer.

Parker's stories are all nominally fantasies, but many of them lack explicit magic, and all are set in a quasi-historical past, seeming to resemble Earth of some centuries or a couple millenia past. Names often echo Latin or Greek. Thus they have a distinct feeling of being historical novels to some degree. As it happens, in 1989, Holt published an historical novel set in Classical Greece, the time of Pericles, Socrates, and Euripides. This novel was called Goat Song, and its sequel, The Walled Orchard, appeared the following year. The two books really form a single novel, and they were later published together under the title The Walled Orchard. Holt has published several further historical novels, set in Hellenistic and later times: Alexander at the World's End (a loose sequel to The Walled Orchard), Olympiad, The Song of Nero, and Meadowland. Eventually he decided to publish these historical novels as by "Thomas Holt". These novels are all darkly comic, cynical, and full of plausible detail about the history and politics involved.

Of one of Parker's stories I observed that it is about the problems caused by both love and war, and in fact that theme runs through a number of his stories, including most obviously the Engineer Trilogy. And that theme is utterly central to The Walled Orchard, which I consider his masterpiece, both in the correct sense (the work that proved his ability as a master craftsman), and in the more common contemporary sense: his best and deepest story. The Walled Orchard is very very funny, but in the darkest of ways, and it is ultimately a true tragedy (after all, the title of the original first volume, Goat Song, means tragedy), and very moving indeed.

The novel is told by Eupolis of Pallene, a Greek dramatist, a writer of comedies, and a rival of Aristophanes. He is writing the history of his times, which ends up being the history of the fall of Athens from its place of importance. It's also of course the story of his life, and the story of his love for his wife, Phaedra, whom he loves desperately and also cannot stand, cannot live with.

I won't go into much detail about the plot. It concerns Eupolis' playwrighting, the contests Athens had every year for plays, as well as Athenian politics, and the original democracy. But ultimately it concerns the Athenian adventure at Syracuse on Sicily, during the Pelopennesian War, which ended in complete disaster for Athens. Eupolis is conscripted to fight at Syracuse, and he is one of the few survivors, hence this history. There's much more going on that that of course, but much of the burden of the novel is the horrors and folly of war, especially as experience at the walled orchard on Sicily.

As I said, it's a truly powerful and moving novel, both in its depiction of war, and also in the terribly sad love story of Eupolis and Phaedra. But it remains blackly funny as well. In the end, very true. And ... I will say, rereading passages of the novel, the connections with K. J. Parker's work, and voice, seem extremely obvious. To conclude -- one of the great historical novels of the past few decades, and a somewhat neglected one, I suspect because Holt's name is stereotyped as a writer of light comedies.

A review by Rich Horton

Tom Holt recently made a fair amount of news when he outed himself as the man behind the "K. J. Parker" pseudonym. This was not exactly a major shock -- Holt was by far the name most commonly suggested as being behind the Parker name. There were those who though Parker might be a woman (a notion I always thought unlikely, not because of any sense that the writing was "ineluctably masculine", but because of the treatment of men, women, and their relationships in Parker's books). Others were thrown off by stunts like Holt's publishing an "interview" with "Parker" at Subterranean a few years ago.

Tom Holt recently made a fair amount of news when he outed himself as the man behind the "K. J. Parker" pseudonym. This was not exactly a major shock -- Holt was by far the name most commonly suggested as being behind the Parker name. There were those who though Parker might be a woman (a notion I always thought unlikely, not because of any sense that the writing was "ineluctably masculine", but because of the treatment of men, women, and their relationships in Parker's books). Others were thrown off by stunts like Holt's publishing an "interview" with "Parker" at Subterranean a few years ago. As for me, in the December 2010 issue of Locus I wrote the following: "I had more pleasure reading K J. Parker’s Blue and Gold than just about anything I've read all year. It features a beautifully constructed plot, plenty of cynical jokes and even some worthwhile commentary on man as a political beast. The story is set in what seemed to me something of an alternate Rome or Byzantium, perhaps a bit like the Rome of Avram Davidson's Vergil stories or his Peregrine stories. It concerns one Saloninus, who opens the book by telling someone "In the morning I discovered the secret of changing base metal into gold. In the afternoon, I murdered my wife." Whether either or both or neither of these claims is true is much of what the story is about, as well as what to make of his relationship with his city’s ruler, Prince Phocas. This is an extremely funny story through and through. The humor, and some of the darkness behind it, reminded me a good deal of Tom Holt's masterpiece, The Walled Orchard, which is close to as high praise as I have in me." Obviously that put me in the Holt=Parker camp, and after that I stayed silent on the subject at request, in order to keep a confidence.

Blue and Gold was one of the first "K. J. Parker" stories I read, and I have read many since, including several novels, among them the Engineer Trilogy, possibly his most famous work. I like them all, for the voice, yes, and for the intricate plots, and for the intriguing details of ancient technology and politics, and for the neat magic systems (when magic is present, that is), and for the dark but not quite despairing view of human nature.

I daresay most readers know Tom Holt best for his humorous fantasies, which began appearing in 1987 with Expecting Someone Taller. These are very funny and clever, and I read them happily for a while, but they began to seem a bit samey-samey after the first few. Since then I've sampled a couple more, with modest but not tremendous enjoyment. Holt also wrote a couple of sequels to E. F. Benson's series of books about Lucia and Mrs. Mapp (which I have not read because I tried the first of Benson's Lucia novels and disliked it), and, famously and (to Holt) embarrassingly, a collection of poems published when he was 13. I am not sure that I would ever have thought that K. J. Parker and the Tom Holt of the humorous fantasies were the same writer.

Parker's stories are all nominally fantasies, but many of them lack explicit magic, and all are set in a quasi-historical past, seeming to resemble Earth of some centuries or a couple millenia past. Names often echo Latin or Greek. Thus they have a distinct feeling of being historical novels to some degree. As it happens, in 1989, Holt published an historical novel set in Classical Greece, the time of Pericles, Socrates, and Euripides. This novel was called Goat Song, and its sequel, The Walled Orchard, appeared the following year. The two books really form a single novel, and they were later published together under the title The Walled Orchard. Holt has published several further historical novels, set in Hellenistic and later times: Alexander at the World's End (a loose sequel to The Walled Orchard), Olympiad, The Song of Nero, and Meadowland. Eventually he decided to publish these historical novels as by "Thomas Holt". These novels are all darkly comic, cynical, and full of plausible detail about the history and politics involved.

Of one of Parker's stories I observed that it is about the problems caused by both love and war, and in fact that theme runs through a number of his stories, including most obviously the Engineer Trilogy. And that theme is utterly central to The Walled Orchard, which I consider his masterpiece, both in the correct sense (the work that proved his ability as a master craftsman), and in the more common contemporary sense: his best and deepest story. The Walled Orchard is very very funny, but in the darkest of ways, and it is ultimately a true tragedy (after all, the title of the original first volume, Goat Song, means tragedy), and very moving indeed.

The novel is told by Eupolis of Pallene, a Greek dramatist, a writer of comedies, and a rival of Aristophanes. He is writing the history of his times, which ends up being the history of the fall of Athens from its place of importance. It's also of course the story of his life, and the story of his love for his wife, Phaedra, whom he loves desperately and also cannot stand, cannot live with.

I won't go into much detail about the plot. It concerns Eupolis' playwrighting, the contests Athens had every year for plays, as well as Athenian politics, and the original democracy. But ultimately it concerns the Athenian adventure at Syracuse on Sicily, during the Pelopennesian War, which ended in complete disaster for Athens. Eupolis is conscripted to fight at Syracuse, and he is one of the few survivors, hence this history. There's much more going on that that of course, but much of the burden of the novel is the horrors and folly of war, especially as experience at the walled orchard on Sicily.

As I said, it's a truly powerful and moving novel, both in its depiction of war, and also in the terribly sad love story of Eupolis and Phaedra. But it remains blackly funny as well. In the end, very true. And ... I will say, rereading passages of the novel, the connections with K. J. Parker's work, and voice, seem extremely obvious. To conclude -- one of the great historical novels of the past few decades, and a somewhat neglected one, I suspect because Holt's name is stereotyped as a writer of light comedies.

Friday, May 8, 2015

Newish, Not a Bestseller, hopefully not Forgotten: Remains, by Mark W. Tiedemann

Remains, by Mark Tiedemann

A review by Rich Horton

Not ready to post about the last Old Bestseller I've read, so I'll post a review of a fairly recent novel, from 2005, Science Fiction, certainly not a bestseller (alas) … and hopefully not forgotten, but a novel that really never got a lot of notice. I say not a lot, but I should note that it was shortlisted for the 2005 Tiptree Award (which frankly surprised me (and the author) as gender does not strike me as a particularly front and center concern of the novel – that said, I'm happy it got the nod). At any rate, however, the novel in question, Mark Tiedemann's Remains, was published by a small press, BenBella , which is best known for “smart pop” books (examples include an Adam-Troy Castro book on Amazing Race, the TV show; and a Mad Men cookbook; as well as books on True Blood, Divergent, etc.). To put it simply, the novel qualifies as a prime example of the phenomenon called “Death of the Midlist”.

Full disclosure here – Mark Tiedemann is a friend of mine, a fellow St. Louisan, and I regularly attend a book group he hosts at Left Bank Books in the Central West End of St. Louis. This month we (the group members) had decided to read one of Mark's books, as he had to miss last month's get-together due to arm surgery. And the book we chose was Remains.

Remains is a pure Science Fiction novel, and also a mystery, and a love story, and it integrates all those elements quite seamlessly. It is set in the 22nd Century, mostly on Aea, an O'Neill cylinder at the Earth/Moon L5 point. Earth has first shunned its space colonies after they asserted their independence, and subsequently they seem to have experienced some apocalyptic disaster, leaving the colonies essentially isolated, with a combined population of only a few million. These colonies are on the Moon (Lunase), in Earth orbit (Aea and others), on Mars, and in a few other places.

The novel opens with Mace Preston, a security professional for PolyCarb Corporation, investigating a disaster at Hellas Planitia on Mars, where a PolyCarb manufactured shield was destroyed in a dust storm. Mace has shoehorned himself into the investigation because his wife Helen was at Hellas Planitia. But before long he is shouldered aside, forced to concede his wife's death, even as the corporation denies she was at the site, and even as her body was never found.

A few years later he is back at Aea, having retired and living quite comfortably off the proceeds of his wife's life insurance as well as some settlement money PolyCarb has given him. After some time privately trying to find out what really happened on Mars, he has largely given up, but has not precisely recovered from his wife's death. A friend, a high-level PolyCarb employee, throws him a party, and he surprises himself by having a good time and going home with Nemily Dollard, a fairly recent immigrant from Lunase.

Nemily, it turns out, is a cyberlink: due to a congenital disorder, she has a mental handicap that is cured by a variety of implants in her brain, that she can switch out as desired: one for mathematical assistance, one called “sensualist”, a synthesist, etc. This is the most Sfnally interesting part of the book: it's an interesting idea on its own, and it's used well to portray Nemily's own difficulty with accepting her individual identity – most notably, she has a hard timing believing she can love. (And an earlier career included “ghosting” – taking on other personalities via her cyberlink for prostitution (a career which does not seem to be held in particular disdain in Aea's culture, I note).)

In rapid order, Mace and Nemily are falling love, while both their pasts begin to intersect. Nemily was used by someone from Lunase to smuggle in some contraband when she emigrated to Aea; and it begins to seem that this person might be related to a series of disasters on various space habitats. It also begins to seem that these disasters might be related to the one on Hellas Planitia that killed Mace's wife – only, is she really dead?

That sets up a pretty neat thriller plot, which has a good and slightly (plausibly) messy resolution. The central love story – or pair of love stories, because the question Mace's marriage to Helen, and whether or not she loved him, is also critical to the book – is quite nicely handled as well. And the book is also full of nice Science Fictional ideas.

I don't think it's fair to call the book forgotten, after only 10 years. (And it is still available from BenBella, and at least at a couple of St. Louis bookstores, including Left Bank Books.) But it is a book that never seemed to me to get the attention it deserved on first release, and it's a book that still deserves a look.

A review by Rich Horton

Not ready to post about the last Old Bestseller I've read, so I'll post a review of a fairly recent novel, from 2005, Science Fiction, certainly not a bestseller (alas) … and hopefully not forgotten, but a novel that really never got a lot of notice. I say not a lot, but I should note that it was shortlisted for the 2005 Tiptree Award (which frankly surprised me (and the author) as gender does not strike me as a particularly front and center concern of the novel – that said, I'm happy it got the nod). At any rate, however, the novel in question, Mark Tiedemann's Remains, was published by a small press, BenBella , which is best known for “smart pop” books (examples include an Adam-Troy Castro book on Amazing Race, the TV show; and a Mad Men cookbook; as well as books on True Blood, Divergent, etc.). To put it simply, the novel qualifies as a prime example of the phenomenon called “Death of the Midlist”.

Full disclosure here – Mark Tiedemann is a friend of mine, a fellow St. Louisan, and I regularly attend a book group he hosts at Left Bank Books in the Central West End of St. Louis. This month we (the group members) had decided to read one of Mark's books, as he had to miss last month's get-together due to arm surgery. And the book we chose was Remains.

Remains is a pure Science Fiction novel, and also a mystery, and a love story, and it integrates all those elements quite seamlessly. It is set in the 22nd Century, mostly on Aea, an O'Neill cylinder at the Earth/Moon L5 point. Earth has first shunned its space colonies after they asserted their independence, and subsequently they seem to have experienced some apocalyptic disaster, leaving the colonies essentially isolated, with a combined population of only a few million. These colonies are on the Moon (Lunase), in Earth orbit (Aea and others), on Mars, and in a few other places.

The novel opens with Mace Preston, a security professional for PolyCarb Corporation, investigating a disaster at Hellas Planitia on Mars, where a PolyCarb manufactured shield was destroyed in a dust storm. Mace has shoehorned himself into the investigation because his wife Helen was at Hellas Planitia. But before long he is shouldered aside, forced to concede his wife's death, even as the corporation denies she was at the site, and even as her body was never found.

A few years later he is back at Aea, having retired and living quite comfortably off the proceeds of his wife's life insurance as well as some settlement money PolyCarb has given him. After some time privately trying to find out what really happened on Mars, he has largely given up, but has not precisely recovered from his wife's death. A friend, a high-level PolyCarb employee, throws him a party, and he surprises himself by having a good time and going home with Nemily Dollard, a fairly recent immigrant from Lunase.

Nemily, it turns out, is a cyberlink: due to a congenital disorder, she has a mental handicap that is cured by a variety of implants in her brain, that she can switch out as desired: one for mathematical assistance, one called “sensualist”, a synthesist, etc. This is the most Sfnally interesting part of the book: it's an interesting idea on its own, and it's used well to portray Nemily's own difficulty with accepting her individual identity – most notably, she has a hard timing believing she can love. (And an earlier career included “ghosting” – taking on other personalities via her cyberlink for prostitution (a career which does not seem to be held in particular disdain in Aea's culture, I note).)

In rapid order, Mace and Nemily are falling love, while both their pasts begin to intersect. Nemily was used by someone from Lunase to smuggle in some contraband when she emigrated to Aea; and it begins to seem that this person might be related to a series of disasters on various space habitats. It also begins to seem that these disasters might be related to the one on Hellas Planitia that killed Mace's wife – only, is she really dead?

That sets up a pretty neat thriller plot, which has a good and slightly (plausibly) messy resolution. The central love story – or pair of love stories, because the question Mace's marriage to Helen, and whether or not she loved him, is also critical to the book – is quite nicely handled as well. And the book is also full of nice Science Fictional ideas.

I don't think it's fair to call the book forgotten, after only 10 years. (And it is still available from BenBella, and at least at a couple of St. Louis bookstores, including Left Bank Books.) But it is a book that never seemed to me to get the attention it deserved on first release, and it's a book that still deserves a look.

Thursday, April 30, 2015

Old Bestsellers: Love Insurance, by Earl Derr Biggers

Old Bestsellers: Love Insurance, by Earl Derr Biggers

Old Bestsellers: Love Insurance, by Earl Derr Biggersa review by Rich Horton

Earl Derr Biggers (1884-1933) was an Ohio native, educated at Harvard, who worked for the Cleveland Plain-Dealer before turning to fiction and plays. He had a fair amount of success early on, and a number of his novels were filmed, but his real success came somewhat late in his shortish life, with a series of books about a Chinese-American detective in Honolulu, Charlie Chan. (Chan was based on an actual Hawaiian detective of Chinese descent, Chang Apana.)

Love Insurance comes from earlier in Biggers' career. It was published in 1914. Like a surprising number of the books I cover in this series, it turns out to have been the basis for a fairly significant movie. In this case the movie was One Night in the Tropics (1940), the first film to feature Abbott and Costello. (The two have a fairly minor role in the film, but apparently stole the show, among other things doing an abbreviated version of "Who's on First?") (Love Insurance was also twice made into a silent movie.)

The book opens with a British aristocrat, Lord Harrowby, visiting Lloyd's of London's New York office with a proposition: he wants them to insure the prospect of his marriage to an American heiress. It seems he needs her money to settle his debts, and if for some reason the marriage doesn't go off, at least the insurance policy will clear what he owes. Lloyd's sends a young man, Dick Minot, down to Florida where the wedding is scheduled to keep an eye on Harrowby, and on the others involved, and make sure the wedding goes through.

On the train to Florida, Minot chances across a very pretty girl; and indeed after the train breaks down, he and she engage an automobile to take them the last stage to their destination, San Marco, FL. Of course it turns out that the girl is Cynthia Meyrick, and she is headed to San Marco to marry Lord Harrowby. (San Marco is a real place, now a neighborhood in Jacksonville, but back then apparently a separate town.) It will hardly come as a surprise that Minot has already fallen for Cynthia, and that he is now faced with the agonizing duty to honorably fulfill his mission for Lloyd's and resist the temptation to let the wedding fail to come off and leave him free to court Cynthia.

And so he does, even as a whole variety of occurrences conspire to interfere with the wedding: a jewel thief, blackmailing newspapermen, a rival claimant to Lord Harrowby's title, Lord Harrowby's apparent cold feet, etc. etc. There are other comic bits, most notably a friend of Minot's who makes money by selling jokes to a rich old lady so she can get a reputation as the wittiest woman in San Marco.

We all know pretty much how things will conclude. The novel gets there bouncily enough, though often in quite preposterous fashion. It fits into the category of books that it doesn't surprise me were once popular, but which don't seem destined to ever be read much again, and which don't seem to deserve a revival.

My edition seems to be possibly a first, from Bobbs-Merrill. It was illustrated, pleasantly enough, by Frank Snapp. The 1940 movie, by the way, is a loosish adaptation, though it does retain the fundamental plot devices. But for example San Marco has become a South American country instead of a Jacksonville exurb. And the Abbott and Costello characters are not to be found in the book (though they may be vague amalgams of a few different characters). Still and all, seems like a movie that might be worth checking out.

Thursday, April 16, 2015

Old Bestsellers: Bound to Rise, by Horatio Alger, Jr.

Old Bestsellers: Bound to Rise, by Horatio Alger, Jr.

A review by Rich Horton

A review by Rich Horton

Back to the later middle 19th Century, and one of the most famous American popular writers of that time. Horatio Alger is best known for “rags to riches” stories of poor young men making their fortunes through hard work.

Horatio Alger, Jr., was born in 1832. His father was a Unitarian minister, of old American stock (several Pilgrims were among his ancestors), but not well off. Young Horatio was a good student, and ended up graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard. He became a minister himself, but was eventually dismissed after allegations of overfamiliarity with the young boys in his congregation. Alger had published occasion stories, poems, and articles to this point, and he turned to more active writing. A few books for adults followed, with limited success. His métier was established with the publication of Ragged Dick in 1868. Most of the books that followed (around a hundred by the end of his life) were very similar: a poor boy, through hard work (and often enough the fortuitous financial assistance of an older wealthy man who the boy might impress through courage or honesty), attains respectably middle class status. Later in his life Alger’s books became a bit more sensational in content, in response to changing public taste. Though his books sold reasonably well, his financial position was never secure. He never married, and that, coupled with the early accusations that cost him his ministerial career, along with veiled references attributed to Henry James, or discovered in some of his books, leads to the assumption by many that he was homosexual, though no hard evidence is available. (Not too surprising, given the views of the times, and the likely affect any such revelation might have had on the sales of his books for boys.)

Alger’s reputation was probably at its highest in the decades just after his death, when reprints of his books sold very widely. But by the middle of the century he was no longer much read, and frankly I doubt he will ever be much read again.

As far as I can tell the book I read, Bound to Rise, is from 1872. It is a reprint, from at a guess somewhere around 1920, published by M. A. Donohue, as part of a series of very inexpensive reprints.

Bound to Rise seems entirely typical of Alger's output. As the story opens, Harry Walton is 14 years old (though the first page says 12 … but 14 is soon after established as correct). His father is a poor farmer in New Hampshire, with six children, just barely scraping by until his cow dies. He is forced to buy a new cow on credit from miserly Squire Green. Harry, after finishing school as the prize student, decides to go off on his own and find a job, hoping to pay back his father's debt.

He spends some time work in a shoemaker's shop, and earns some decent money, while virtuously refusing to waste it on clothes or pool or cigars or any other vice. Thereby he makes an enemy of a dissolute fellow worker, who is always in debt to his tailor. Harry's first catastrophe is when he loses his pocketbook and the other boy steals it … but that is soon rectified. Then the shoe business slows, but Harry finds a place with a magician. Soon he's making even more money – enough to pay off his father's debt, but disaster strikes again when Harry is robbed at gunpoint. In this case he is saved by an even more fortuitous event (the thief steals Harry's fine overcoat, but leaves him his own shabby one in recompense, and forgets that his (the thief's) pocketbook, with even more money than was stolen, is in the overcoat). The novel ends, somewhat abruptly, as the magician, having fallen sick, releases Harry to his next job, his dream job, working for a printer. (Harry is fascinated by Ben Franklin, and eventually wants to be an editor.) Before taking up his new position, Harry returns home to pay off his father's debt, to the discomfiture of the evil Squire Green.

There's little enough action there, to be sure. And if the novel seems incomplete – it was: there was an immediate sequel, Risen from the Ranks. It's really not terribly interesting. Alger's style was quite prosy, and moralizing. He also had the habit of half-describing something interesting, then saying something like “but our story need not dwell on this detail ...” and going on. Women are not very present in the novel, and there is never a suggestion that Harry even notices girls, nor that he ever thinks of a relationship with one. And Harry's path is quite straightforward … he is a hard worker, and thrifty, but otherwise opportunities are thrown willy-nilly in his path, and difficulties are overcome with sheer good luck. All in all, just not a very good book, but it is possible to see why it and its fellows were once very popular.

A review by Rich Horton

A review by Rich HortonBack to the later middle 19th Century, and one of the most famous American popular writers of that time. Horatio Alger is best known for “rags to riches” stories of poor young men making their fortunes through hard work.

Horatio Alger, Jr., was born in 1832. His father was a Unitarian minister, of old American stock (several Pilgrims were among his ancestors), but not well off. Young Horatio was a good student, and ended up graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard. He became a minister himself, but was eventually dismissed after allegations of overfamiliarity with the young boys in his congregation. Alger had published occasion stories, poems, and articles to this point, and he turned to more active writing. A few books for adults followed, with limited success. His métier was established with the publication of Ragged Dick in 1868. Most of the books that followed (around a hundred by the end of his life) were very similar: a poor boy, through hard work (and often enough the fortuitous financial assistance of an older wealthy man who the boy might impress through courage or honesty), attains respectably middle class status. Later in his life Alger’s books became a bit more sensational in content, in response to changing public taste. Though his books sold reasonably well, his financial position was never secure. He never married, and that, coupled with the early accusations that cost him his ministerial career, along with veiled references attributed to Henry James, or discovered in some of his books, leads to the assumption by many that he was homosexual, though no hard evidence is available. (Not too surprising, given the views of the times, and the likely affect any such revelation might have had on the sales of his books for boys.)

Alger’s reputation was probably at its highest in the decades just after his death, when reprints of his books sold very widely. But by the middle of the century he was no longer much read, and frankly I doubt he will ever be much read again.

As far as I can tell the book I read, Bound to Rise, is from 1872. It is a reprint, from at a guess somewhere around 1920, published by M. A. Donohue, as part of a series of very inexpensive reprints.

Bound to Rise seems entirely typical of Alger's output. As the story opens, Harry Walton is 14 years old (though the first page says 12 … but 14 is soon after established as correct). His father is a poor farmer in New Hampshire, with six children, just barely scraping by until his cow dies. He is forced to buy a new cow on credit from miserly Squire Green. Harry, after finishing school as the prize student, decides to go off on his own and find a job, hoping to pay back his father's debt.

He spends some time work in a shoemaker's shop, and earns some decent money, while virtuously refusing to waste it on clothes or pool or cigars or any other vice. Thereby he makes an enemy of a dissolute fellow worker, who is always in debt to his tailor. Harry's first catastrophe is when he loses his pocketbook and the other boy steals it … but that is soon rectified. Then the shoe business slows, but Harry finds a place with a magician. Soon he's making even more money – enough to pay off his father's debt, but disaster strikes again when Harry is robbed at gunpoint. In this case he is saved by an even more fortuitous event (the thief steals Harry's fine overcoat, but leaves him his own shabby one in recompense, and forgets that his (the thief's) pocketbook, with even more money than was stolen, is in the overcoat). The novel ends, somewhat abruptly, as the magician, having fallen sick, releases Harry to his next job, his dream job, working for a printer. (Harry is fascinated by Ben Franklin, and eventually wants to be an editor.) Before taking up his new position, Harry returns home to pay off his father's debt, to the discomfiture of the evil Squire Green.

There's little enough action there, to be sure. And if the novel seems incomplete – it was: there was an immediate sequel, Risen from the Ranks. It's really not terribly interesting. Alger's style was quite prosy, and moralizing. He also had the habit of half-describing something interesting, then saying something like “but our story need not dwell on this detail ...” and going on. Women are not very present in the novel, and there is never a suggestion that Harry even notices girls, nor that he ever thinks of a relationship with one. And Harry's path is quite straightforward … he is a hard worker, and thrifty, but otherwise opportunities are thrown willy-nilly in his path, and difficulties are overcome with sheer good luck. All in all, just not a very good book, but it is possible to see why it and its fellows were once very popular.

Thursday, April 9, 2015

Old Bestsellers: I Love You, I Love You, I Love You, by Ludwig Bemelmans

Old Bestsellers: I Love You, I Love You, I Love You, by Ludwig Bemelmans

a review by Rich Horton

I dare say most of you have heard of, and indeed have read, at least one and possibly several books by Ludwig Bemelmans. He was the author of a delightful series of children's books about a little girl named Madeline, who went to a boarding school in Paris. The opening lines are widely remembered: "In an old house in Paris all covered with vines/lived twelve little girls in two straight lines/and the smallest one was Madeline." My mother read those books to me when I was young, and I read them to my children when they were young. Indeed, I read them to my daughter probably dozens of times.

By now I think that is all Bemelmans is remembered for. But in his prime he was an active writer of mostly humorous short stories, published in places like Harper's and the New Yorker. He wrote movie scripts as well, and a well-received memoir of his experiences as a not fully trusted volunteer in the U. S. Army during World War I (My War with the United States).

Bemelmans was born in the Tyrol, in what was then Austria-Hungary (it is now Italy), to a Belgian father and a German mother, in 1898. After his father ran off with Ludwig's governess, his mother returned to Germany, which Ludwig disliked. He eventually took an apprentice position at a hotel, but after shooting (though not killing) a waiter, he chose to be deported to the US in lieu of reform school. He worked in hotels and restaurants in the US, spent time in the Army, as noted above, and tried to make it as an artist, among other things briefly writing a comic strip. His friendship with a children's book editor at Viking, May Massee, seems to have been his big break.

I Love You, I Love You, I Love You was published in 1942 by Viking. My edition is a paperback from Signet, published in 1948. There are 12 stories included, all quite short, probably totalling no more than 30,000 words. The stories are "Souvenir", "I Love You, I Love You, I Love You", "Star of Hope", "Pale Hands", "Watch the Birdie", "Bride of Berchtesgaden", "Chagrin D'Amour", "Head-Hunters of the Quito Hills", "Vacation", "Cher Ami", "Camp Nomopo", and "Sweet Death in the Electric Chair". They are illustrated liberally by the author, in a style immediately recognizable to readers of the Madeline books.

Bemelmans, as noted, worked in hotels and restaurants for much of his life. He also owned a restaurant (later a cabaret); and he travelled very widely. So it is no surprise that the bulk of the stories here concern travel, such as the opener, "Souvenir", which has almost no plot as it tells of a trip to France (and back) on the Normandie, one way in a luxury suite, then in third class on the way back. The narrator usually seems to be Bemelmans himself, and very often his daughter Barbara is an important character. For example, "I Love You, I Love You, I Love You" opens suggestively, with a girl slipping into bed with the narrator ... but soon we realize it's his very young daughter. In the end it's about her wheedling ways, and her friendship with a small-time thief named Georges. "Camp Nomopo" is about Barbara again, this time her unhappiness at summer camp. Georges appears again in the following story, "Star of Hope", complaining that the French aren't allowing him to make a dishonest living, and wishing he could be in America, where things are much better. Georges, possibly the same character, shows up again in the next story, helping an art dealer smuggle a painting out of the hands of the Nazis. That is one of a couple of stories that balance the generally light-hearted tone of the collection with mention of the war -- the stories remain humorous but not inappropriately.

"Watch the Birdie" concerns a photographer of nudes and his unsuccessful attempts to practice his art on a beautiful American model, after which he ends up in the US and is chagrined when his agent offhandedly reveals his fortuitous success with the same young woman. "Chagrin D'Amour" feels just a bit dated ... it's set at a Haitian hotel, and turns on a supposed twist, when it is revealed that the local policeman who is in love with a pretty lady's maid is black. "Head-Hunters of the Quito Hills" is another amusing travel story, in which the narrator visits Ecuador, only to be repeatedly importuned by offers to sell him shrunken heads ... he finally learns the secret of their manufacture.

The stories as a whole are a rather slight lot, and very much of their time. But they are an easy, pleasant, read. They are humorous, but not uproariously funny. I wouldn't go out of my way to find more "adult" Bemelmans, but I'm glad to have run across this little book.

a review by Rich Horton

I dare say most of you have heard of, and indeed have read, at least one and possibly several books by Ludwig Bemelmans. He was the author of a delightful series of children's books about a little girl named Madeline, who went to a boarding school in Paris. The opening lines are widely remembered: "In an old house in Paris all covered with vines/lived twelve little girls in two straight lines/and the smallest one was Madeline." My mother read those books to me when I was young, and I read them to my children when they were young. Indeed, I read them to my daughter probably dozens of times.

By now I think that is all Bemelmans is remembered for. But in his prime he was an active writer of mostly humorous short stories, published in places like Harper's and the New Yorker. He wrote movie scripts as well, and a well-received memoir of his experiences as a not fully trusted volunteer in the U. S. Army during World War I (My War with the United States).

Bemelmans was born in the Tyrol, in what was then Austria-Hungary (it is now Italy), to a Belgian father and a German mother, in 1898. After his father ran off with Ludwig's governess, his mother returned to Germany, which Ludwig disliked. He eventually took an apprentice position at a hotel, but after shooting (though not killing) a waiter, he chose to be deported to the US in lieu of reform school. He worked in hotels and restaurants in the US, spent time in the Army, as noted above, and tried to make it as an artist, among other things briefly writing a comic strip. His friendship with a children's book editor at Viking, May Massee, seems to have been his big break.

I Love You, I Love You, I Love You was published in 1942 by Viking. My edition is a paperback from Signet, published in 1948. There are 12 stories included, all quite short, probably totalling no more than 30,000 words. The stories are "Souvenir", "I Love You, I Love You, I Love You", "Star of Hope", "Pale Hands", "Watch the Birdie", "Bride of Berchtesgaden", "Chagrin D'Amour", "Head-Hunters of the Quito Hills", "Vacation", "Cher Ami", "Camp Nomopo", and "Sweet Death in the Electric Chair". They are illustrated liberally by the author, in a style immediately recognizable to readers of the Madeline books.

Bemelmans, as noted, worked in hotels and restaurants for much of his life. He also owned a restaurant (later a cabaret); and he travelled very widely. So it is no surprise that the bulk of the stories here concern travel, such as the opener, "Souvenir", which has almost no plot as it tells of a trip to France (and back) on the Normandie, one way in a luxury suite, then in third class on the way back. The narrator usually seems to be Bemelmans himself, and very often his daughter Barbara is an important character. For example, "I Love You, I Love You, I Love You" opens suggestively, with a girl slipping into bed with the narrator ... but soon we realize it's his very young daughter. In the end it's about her wheedling ways, and her friendship with a small-time thief named Georges. "Camp Nomopo" is about Barbara again, this time her unhappiness at summer camp. Georges appears again in the following story, "Star of Hope", complaining that the French aren't allowing him to make a dishonest living, and wishing he could be in America, where things are much better. Georges, possibly the same character, shows up again in the next story, helping an art dealer smuggle a painting out of the hands of the Nazis. That is one of a couple of stories that balance the generally light-hearted tone of the collection with mention of the war -- the stories remain humorous but not inappropriately.

"Watch the Birdie" concerns a photographer of nudes and his unsuccessful attempts to practice his art on a beautiful American model, after which he ends up in the US and is chagrined when his agent offhandedly reveals his fortuitous success with the same young woman. "Chagrin D'Amour" feels just a bit dated ... it's set at a Haitian hotel, and turns on a supposed twist, when it is revealed that the local policeman who is in love with a pretty lady's maid is black. "Head-Hunters of the Quito Hills" is another amusing travel story, in which the narrator visits Ecuador, only to be repeatedly importuned by offers to sell him shrunken heads ... he finally learns the secret of their manufacture.

The stories as a whole are a rather slight lot, and very much of their time. But they are an easy, pleasant, read. They are humorous, but not uproariously funny. I wouldn't go out of my way to find more "adult" Bemelmans, but I'm glad to have run across this little book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)