Wednesday, October 22, 2014

Old Bestsellers: Heyday, by W. M. Spackman

Heyday, by W. M. Spackman

A review by Rich Horton

I'm cheating a bit here ... this wasn't a bestseller (though I think it did OK), and it's not quite as old as the usual parameters of this series. (I like to stay pre-1950, and this book is from 1953.) It's also not exactly forgotten, though it was in danger of being forgotten when Spackman's career stalled for a couple of decades as he couldn't sell his (outstanding) second novel.

One of my favorite 20th Century American writers is W. M. Spackman. Spackman was a Quaker, of old family and old money, born in 1905, a member of the Princeton Class of 1927. The depression apparently ruined his plans for his life (he lost all his money), and he spent some time in journalism and radio, before ending up in academe in the 50s, though after selling his first novel he returned to Princeton to write (but apparently not to teach). His first novel was Heyday, published in 1953, when he was 48. It was apparently a modest success. His next novel, An Armful of Warm Girl, was finished by 1959 or so, but he couldn't sell it. He concentrated on his academic work then, publishing some well-regarded essays and a collection of poems, until An Armful of Warm Girl was rediscovered and eventually published in Harper's in 1977, and as a book in 1978. Three more novels were published by 1985 (A Presence with Secrets, A Difference of Design, and A Little Decorum, for Once). Spackman died in 1990, leaving an unpublished novel (As I Sauntered Out, One Midcentury Morning) and some work on a revision to Heyday. All six of these novels (Heyday in its partially revised form) and a couple of short stories were published by the magnificent folks at The Dalkey Archive Press in 1997 as The Collected Fiction of W. M. Spackman. I've written about that book before, I think it's wonderful. The later novels, from Armful on, are generally of a piece -- the plots feature lighthearted adultery, usually between a man in his 50s or older and a somewhat younger woman (the ages range from the late teens to the 40s through the various books). The primary delight of the novels is the prose -- as somebody wrote, "confectionary" -- a breathless, elegant, supple, sheerly gorgeous stream of words -- wry and purposely affected dialogue, ardent descriptions (usually of the inexhaustible charms of beautiful women) -- and constant movement. For some tastes the prose might be too affected, too arch -- though not for me. For many tastes, including mine, if I let it bother me, the plots and situations and characterizations are very classist, arguably sexist, and full of wish-fulfillment. The general mood is comic, though the novels can turn meditative and somewhat melancholy at times.

Heyday is a rather different beast. I have read both versions. The revisions are mostly severe cuts. The original novel, about twice the length of the later revision, was published simultaneously in hardcover and paperback by Ballantine in 1953. The basic subject of the novel, in both forms, is the tribulations of the Princeton Class of 1927 during the Depression. We follow a small group of men and women as they try to find work, hatch silly schemes like riding out the slump on a communal farm, and, mostly, go to parties and sleep with each other. The narrator is a man named Webb Fletcher, a Quaker born in Pennsylvania but raised in Wilmington, Delaware (much like Spackman), but his main interest is chronicling the love life of a distant cousin of his, Malachi ("Mike") Fletcher, also a Quaker and a fellow member of the Class of 1927. The storyline follows Mike as he almost falls in love with Kitty Locke, only to find her long term involvement with a somewhat abusive other man too much to overcome; and as he fends off the desperate attentions of Jill Starr, a fragile woman who is being blatantly cheated on by her husband; then as he enters an affair with Stephanie Lowndesden, only to lose her to Webb, after which he rekindles things with Kitty, even though it is clear his chance for real happiness is gone. In the later, revised, version, that's pretty much all there is (intermixed, to be sure, with some descriptions of Webb's amorous adventures, particularly with Stephanie), but it works pretty well -- it's a desperate portrayal of a rather desperate, not wholly sympathetic, group of people. At the same time it is basically comic, though tinged with melancholy, as what wouldn't be set against the backdrop of the Depression. (And there is only a smidgen of recognition that these characters are privileged and lucky, with resources to fall back on that many a poor person entirely lacked.) The prose is pretty good, though not pitched quite to the level of Spackman's later novels (much of the dialogue is already pure Spackman).

The parts Spackman cut tend to shift the focus quite a bit, and to point a moral rather more explicitly. They also move the novel more to the tragic than comic direction. The original novel opens as Webb Fletcher, a Lt Cdr for Navy Intelligence, finds out that Mike Fletcher has died in the Pacific in 1942, attacking a Japanese ship with his carrier-based plane. (Apparently he was not a Conscientious Objector, even though a Quaker.) Webb begins to reflect on what he knew of Mike, and the ways in which he and his cousin were very similar, and yet also the ways in which Webb was able to avoid Mike's desolate end. (Not so much dying, but entering into a less than satisfactory marriage, it later becomes clear. In the revised version, I don't think it's made clear that Mike's marriage to Kitty is a second-best sort of thing.) And Webb reflects a bit on his Princeton career, and then on a trip to France shortly after college at which he encountered Davy Starr with a silly girl named Jill, and Jill's friend Barbara, or Bar, with whom Webb falls head over heels in love. Webb and Bar are married, then the Depression hits, and they spend some time in Chicago before Webb gets a job in New York. On the way to meet Webb in New York, Bar, not concentrating, runs over three children on a rural road, and gets sent to prison for manslaughter.

Which makes for a slightly lurid opening. The novel continues to the middle section, which is pretty much exactly the revised version, except that explicit references to Webb's being married, and to Bar's travails in prison, are excised. Thus the original version is much more balanced in that it is about both Webb and Mike, and that much of the novel is really concerned with Webb's loneliness, missing Bar, and how his eventual despair (particularly after an early parole chance is denied) nearly leads to what might have been a disastrous affair with Kitty Locke, and does lead to his actually rather sweet, but doomed, affair with Stephanie Lowndesden. Finally, there is a closing section, also cut, detailing Webb's and Bar's reunion in 1937, after she is finally released from prison, and their beginning to rebuild their life (apparently successfully, as far as we can tell from the perspective of 1942). Spackman also takes some care to point out that Webb's eventual salvation was that he fell thoroughly in love with someone, while Mike is portrayed as never having been able to give himself so completely to a woman (there are hints that maybe he should have taken Jill away from Davy Starr). There is also a mild suggestion that Stephanie is tragically, or at least sadly, deprived of her own true love because Webb is already "taken".

All in all the revised version seems a bit more explicitly Fitzgeraldian -- indeed, Spackman himself, in a note at the end of 1953 edition, brings up Fitzgerald. Besides Fitzgerald the most obvious comparison might be the great British novelist Henry Green, born in the same year as Spackman. Another comparison might be with the early novels of yet another great writer born in 1905, Anthony Powell, especially his first, Afternoon Men. Heyday is a pretty good book, one that you would probably call very promising had you encountered it in 1953, but maybe also a bit unsure of itself -- too ready to force a point, as it were. And maybe a bit too overtly portentous.

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Old Bestsellers: The Night Life of the Gods, by Thorne Smith

The Night Life of the Gods, by Thorne Smith

A review by Rich Horton

Thorne Smith of course remains fairly famous as the writer of two novels, Topper and Topper Takes a Trip, about a banker stuck in a boring marriage who is haunted by a funloving ghost couple. These books remain famous probably mostly because of a series of successful movies (starring Cary Grant, in the first film at least) and later a radio show and a TV series.

Smith was born James Thorne Smith, Jr., in 1892. He came from a Naval family, attended Dartmouth, and then spent some time in the Navy. His first couple of books consisted of comic sketches about Biltmore Oswald, a Naval recruit, that were originally written for a Navy magazine. His breakout books was Topper, in 1926. Besides Topper his most successful novels were The Stray Lamb (1929), and The Night Life of the Gods (1931). Smith died in 1934, as far as I can tell having essentially drunk himself to death -- his novels featured heavy drinking (even as, or perhaps because, they were set during Prohibition), and he apparently drank as prodigiously as his characters.

The Night Life of the Gods concerns Hunter Hawk, a successful bachelor inventor who has been forced to take in his sister, her useless husband, her husband's father, and their two children, the awful Alfred Junior and the rather nice Daphne. Hawk invents a petrification ray, which he uses to rather cruelly turn his relatives into stone (and back again, I should say). He wanders off into the countryside and meets a leprechaun, and the leprechaun's enchanting daughter Megaera, or Meg.

Meg falls immediately for Hawk, and leaps into his bed at the first opportunity. She and her father enjoy Hawk's liquor a great deal, and before long they have got him into trouble with the law. They end up at his New York City apartment, from whence they proceed to the Metropolitan Museum, where a reverse process of the petrification ray turns various statues of the Greek gods into living beings.

The rest of the novel concerns the chaos caused by the gods having the time of their "lives" drinking and thieving and pranking their way through New York, and later back into the country where Hawk's other home is. But the law is still after him, and the gods soon tire of the pace of modern life, not to mention the strenght of modern liquor. And Hunter's family is still a problem -- is there a way he can solve his problems so that Daphne comes out OK and the more odious of his family (and neighbors) are punished? The ending is actually rather bittersweet, and in some ways the best thing about the book. It's clear that Hunter Hawk, for all his intelligence and cynicism, and for all that he seems to really love Meg, is not a happy person.

I have to say I wasn't enthralled by the book. It's one of those stories where you can see that it's funny and clever throughout, but somehow that doesn't really strike home. Part of it might be some datedness -- the treatment of sex was perhaps intended to be shocking and titillating but for a contemporary audience that hardly registers. The drinking also perhaps doesn't come off in the same spirit so many years after prohibition, and with it necessary to keep in mind that excessive drinking (and wild driving under the influence) isn't necessarily all that funny. I know that makes me sound like a killjoy, but, well, there you are. It's clearly a well-done book, but not a book I could really love.

Some years ago I had read The Stray Lamb, and I'll reproduce the snippet I wrote about that:

This features a fortyish, rich, investment banker type, in 1928 or so, named T. Lawrence Lamb. Lamb becomes fascinated with a beautiful friend of his daughter, who throws herself at him His wife is a b*tch, so Lamb would like to accept her advances, but he is too strait-laced in habits. Then a mysterious stranger decides to teach him a lesson. He is changed in turn to several different animals, such as a horse, a dog, a seagull, and others. Chaos ensues, his wife leaves him, he learns to be less straitlaced. It's quite fun, often very funny and very clever. A bit forced at times, and a lot convenient. But enjoyable.

Thursday, October 9, 2014

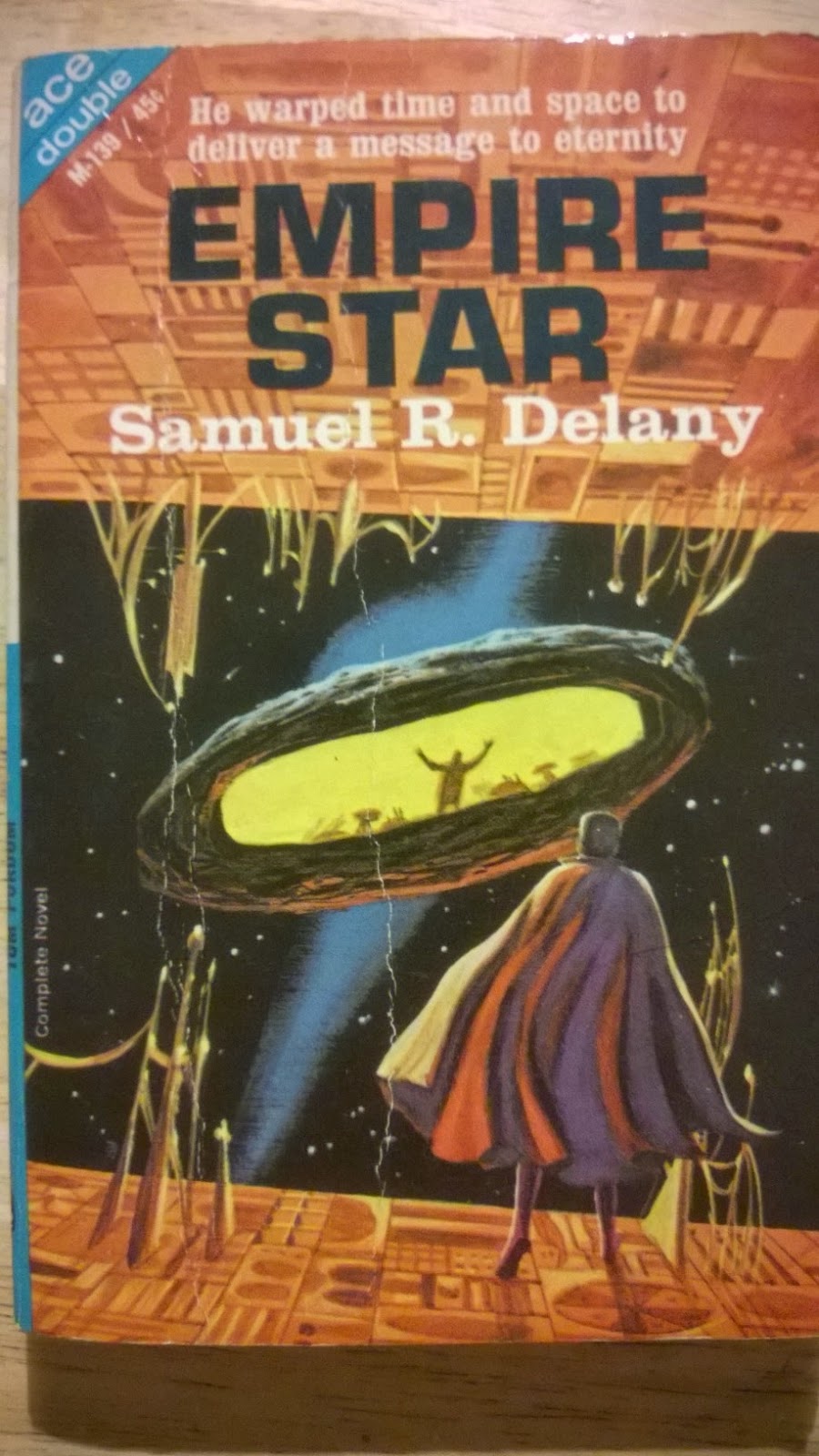

Ace Doubles: Empire Star, by Samuel R. Delany/The Tree Lord of Imeten, by Tom Purdom

Ace Doubles: Empire Star, by Samuel R. Delany/The Tree Lord of Imeten, by Tom Purdom

Ace Doubles: Empire Star, by Samuel R. Delany/The Tree Lord of Imeten, by Tom PurdomA review by Rich Horton

Not having finished reading my latest old bestseller, I'm turning to an Ace Double, as noted previously also an interest of mine. This books pairs a very interesting early novel (or novella) by one of the greatest of SF writers (and a newly minted SFWA Grandmaster) with an enjoyable early novel by a favorite writer of mine, a man whose work flew largely under the radar until a modest increase in visibility engendered by a late career resurgence. So: Samuel R. Delany certainly isn't forgotten, but to an extent Empire Star is underappreciated (in my opinion), and Tom Purdom is surely a writer who deserves a wider audience.

This Ace Double was published in 1966. Empire Star is about 29,000 words long, The Tree Lord of Imeten is about 48,000 words. To the best of my knowledge, neither book appeared in any other form previous to this publication. Delany had 5 novels appear as part of Ace Doubles: his first, The Jewels of Aptor; the first two novels in his Fall of the Towers trilogy; The Ballad of Beta-2, and this one. The Ballad of Beta-2 and Empire Star were later reissued together as #20571 in the last year of Ace Doubles, 1973. My original copy of the two books, bought in 1975 for $1.25, is not bound dos-a-dos like a typical Ace Double -- I think this is a still later reissue of the 1973 Ace Double, but I may be wrong -- perhaps this was the 1973 version (though $1.25 seems a high price).

Samuel R. Delany was justly among the most celebrated SF writers of the 60s and 70s. For me his most congenial work is a remarkable burst of stories and novels from 1966 through 1968 -- those three years saw the publication of his Nebula winning novels Babel-17 and The Einstein Intersection as well as my favorite among his novels, Nova, plus his Nebula winning story "Aye, and Gomorrah", his Nebula and Hugo winner "Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones", and such stories as "The Star Pit", "Driftglass", and "We, in Some Strange Power's Employ, Move on a Rigorous Line". To say that those are my favorites among Delany's work shouldn't be seen as rejecting the value of later stuff such as Trouble on Triton or Tales of Neveryon, which I still enjoy -- it's just that what he did from 1966 through 1968 still impresses me as just plain more fun.

Empire Star came out just at the beginning of this period, in 1966. It is generally grouped with his earlier novels, but in tone it reminds me as much of Babel-17 as any of his stuff, and it quite openly foreshadows aspects of Nova. It doesn't have the enduring reputation of the stories I mentioned above, but it is impressive work, extremely playful in a bravura and quite accomplished fashion -- showing an author clearly besotted with language, clearly interested in allusion and symbolism but still at the point of having fun with it all. It's a thoroughly enjoyable novel, if just that bit less serious than even his slightly later stuff to relegate it to the second rank among his works.

It opens with Comet Jo, a young man on a planet of Tau Ceti devoted to harvesting plyasil and nothing else, encountering a downed alien spaceship and coming into possession of a devil kitten, a crystallized alien called Jewel, and a message to deliver to Empire Star. So he hitches a ride with a spaceship away from Tau Ceti -- despite the fact that he is a simplex boy, and that living in the wider universe may require him to become complex and even multiplex. The story darts rapidly to Earth, to other planets, and to Empire Star; and Jo meets such people as the tortured San Severina, who owns seven enslaved aliens called Lll; and the embodied consciousness of a Lll in a computer -- the Lump; and the suicidal poet Ni Ty Lee, who (like Theodore Sturgeon) seems to have done everything you have done before you could do it; and a Princess escaped from Miss Perrypicker's Academy. What is it about -- well, that's sort of multiplex. It's swift and gay and bittersweet and funny and the ending is delightful, with echoes of Charles Harness but much tighter. It's really a fine work.

Tom Purdom's first story was published in 1957, when he was 21, and over the subsequent 15 years or so he published some 13 stories in a variety of places (Analog, Science Fiction Quarterly, Amazing, Galaxy, etc.) and 5 novels (three of which were Ace Double halves). It would probably be fair to say that he didn't gain a lot of notice, though at least one story made a Wollheim/Carr Best of the Year collection. Then he fell mostly silent until 1990 -- only two stories, one in Galaxy and one in Analog. Beginning in 1990, however, he began to publish short fiction regularly again, most of it in Asimov's, and much of it very impressive indeed. Stories like "Cider", the three "Romance" stories about a Casanova-like character in a posthuman future, and this year's "The Path of the Transgressor" are quite remarkable, as well as later work like 2013's "A Stranger from a Foreign Ship".

So, I am rather an admirer of his latter-day short fiction. I was thus glad when I ran across this Ace Double:-- not only was it a good excuse to reread Empire Star but a good opportunity to try Purdom at novel length, as this was the first of his novels I read. The result is not bad -- The Tree Lord of Imeten isn't a brilliant book at all, and it's noticeably rushed in its conclusion, but it's a fairly original and refreshing story in many ways. It's not as good as Empire Star (not even close) but it's solid work, and the combined Ace Double has to rank as one of the stronger books in the whole series.

Harold is a 21 year old man living in a colony of refugees from a regimented 21st Century Earth. The colony has been established on a plateau on a planet of Delta Pavonis, on a world otherwise dominated by forest, mountain, and ocean. His mother and sister are long dead, and his father and his best friend have just been murdered in some never specified political dispute. A young woman, Joanne, negotiates a deal whereby the two are exiled off the plateau, but not killed.

In the forest they encounter two separate intelligent species -- a ground-dwelling species without hands (just paws) but great linguistic facility; and a tree-dwelling apelike species which has just entered on an Iron Age. The tree-dwellers are violent, and they have enslaved many members of the ground dwelling species. Harold and Joanne are captured by the tree-dwellers, and, sickened by the slaveholding, they scheme to escape and work to free the slaves.

All fairly routine, really, but it's redeemed by a pretty decent job of portraying the two species, particularly the ground-dwellers, and by the fairly well-characterized main characters. Minor effective details are Harold's extreme nearsightedness and Joanne's limp. The plot resolution is a bit rapid, and somewhat conventional. Still, I liked it, and I wondered if Purdom wrote a sequel -- there's definitely room for a story about the eventual contact between the two indigenous species and the rest of the human colony.

As for the sequel I had wondered about: in the past few years (2010-2014) Purdom has published four novelette-length extensions to the story, all published in Asimov's: "Warfriends", "Golva's Ascent", "Warloard", and "Bogdavi's Dream". These follow on fairly directly from the novel, continuing the story of the two alien races and a number of humans: not just Harold and Joanne but other resisters to the (now better explained) political dispute among the human colony. They are very fine work, and I hope we'll eventually see an omnibus of The Tree Lord of Imeten and these follow-on stories.

Thursday, October 2, 2014

Old Bestsellers: The Black Flemings, by Kathleen Norris

The Black Flemings, by Kathleen Norris

The Black Flemings, by Kathleen NorrisA review by Rich Horton

Here again is a book of the sort I consider central to this series ... a popular book from decades ago by a supremely popular writer who is now mostly forgotten.

Kathleen Thompson was born in San Francisco, California, in 1880. Her parents both died in 1899, and she worked in a hardware store to support her siblings, and also began to publish occasional short stories. In 1906 she became the society columnist for the San Franscico Call. She met writer Charles Gilman Norris in the course of that job, and married him in 1909, after he had moved to New York to edit the American Magazine. They had one living child (a pair of twins died in childbirth or shortly after). The Norrises returned to California in 1919. Kathleen Norris died in 1966.

Norris' first novel, Mother (1911), was expanded from a story she wrote for the American. It became a bestseller and was praised by the likes of President Theodore Roosevelt. She began publishing novels regularly, by some accounts publishing as many as 93. Her novels were consistently bestsellers, and two appear on Publishers' Weekly's lists of the Top Ten bestsellers by year: The Heart of Rachael in 1916, and Harriet and the Piper in 1920. She is often called the bestselling woman novelist of the 20th Century -- I'm not sure how this was determined, though. For example, Mary Roberts Rinehart, a very near contemporary of Norris's, and approximately as prolific, appeared on the PW lists of Top Ten Bestsellers of the year 12 times, for 10 different books -- one would think she sold as many or more books as Norris. Norris continued to publish novels at least into the 1950s.

Norris was related by marriage to a number of well-known writers. Her husband was a well-received novelist in his day, most especially for Salt, though he is all but forgotten today. Her brother-in-law, Frank Norris, was much more crtically successful than either of them, and is still remembered, especially for McTeague and The Octopus. Kathleen Norris' sister married poet William Rose Benét, who won the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry in 1942. Though William Rose Benét is hardly read any more, his brother Stephen Vincent Benét, who also won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, is still very well-known. (The Benét's are the only pair of siblings each to have won a Poetry Pulitzer, though cousins Amy Lowell and Robert Lowell also both won the Prize.)

Kathleen Norris was critically regarded as overly sentimental, partly because her books exalted the roles of wife and mother; and no doubt partly because her bestseller plots do seem to have tended towards the sentimental. He relatively low critical regard probably also stems from her prolificity, and too from her financial success. Her husband's work was better received at the time, though she seems to have sold better. Likely her place as a writer of overtly "women's fiction" contributed to her reception as well. It is my sense that she is a writer, unlike many of the writers I've covered in this series (though not all) who may well be worthy of a modest revival. She was a devout Catholic, and an ardent opponent of birth control, though on other political questions, especially having to do with women's rights, her views were more liberal.

The Black Flemings (1926) does not seem to be one of her better known books. (As far as I can tell, her best-received novels, besides the bestsellers already mentioned, include Saturday's Child (1914), Josselyn's Wife (1918), and Certain People of Importance (1922).) It is set in Massachusetts, on the coast, almost entirely in a gloomy old mansion called Wastewater. Wastewater is the home of the Fleming family, but at the time of the action, there is no real head of the family. David Fleming, a distant cousin who was raised by the late Roger Fleming after his widowed mother married him, acts as a financial advisor of sorts. He is level-headed and not terribly ambitious, and spends much of his time painting. He has a sort of intention to marry Roger's niece, Sylvia, who is beautiful and intelligent and "superior". Roger's son (and David's half-brother), Tom, ran away to sea at 14, and had not been heard from since -- he is assumed to be dead, making Sylvia the heir. The mistress of Wastewater is Aunt Flora, another distant cousin, who had twice been engaged to marry Roger, only to be thrown over, first for David's mother and then for Cecily Kent, a frail 17 year old who somehow attracted Roger's attention only to die after only a few unhappy years of marriage. Flora had married Roger's rackety brother Will, who later died, though not before fathering Sylvia.

Into this tangle returns Gabrielle Charpentier, the daughter of Aunt Lily, Flora's younger sister, who went mad and died, partly because her husband, Mr. Charpentier, abandoned her even before Gabrielle's birth. Gabrielle, or Gay, is a beautiful young woman, blond as opposed to the usual brunette of the "Black Flemings", and convent educated. The problem is what to do with her ... she has no money, and little in the way of education. But, we soon realize, she is the true heroine, and her steadfastness, honesty, and good instincts are seen (by the writer and (eventually) the reader) as greater virtues than Sylvia's "superiority" (though it should not be said that Sylvia is at all a bad person). To the reader's non-surprise, she falls for David -- and soon David for her, though he doesn't quite realize it.

The novel develops somewhat slowly (though it remains interesting), and unveils its secrets (which are many) at a rather unconventional pace. It turns mainly on the questions of Gabrielle's birth, about which there are a series of revelations, as well as on such things as the identity of the mysterious old woman whom Gay sometimes sees but whom everyone else denies the existence of; and too of course on the true fate of David's half-brother Tom, who would be the heir to Wastewater and to the Fleming fortune if he were ever to be found; and also on the real history of Roger's adventures with women. So in fact there is a distinct touch of the Gothic to the whole thing, though it's not a full-blown Gothic.

The wrapping up is not really much of a surprise, though the specifics of the working out aren't necessarily exactly as expected. I will say Sylvia's eventual fate seemed a bit tacked-on to me. It really reads quite nicely -- Norris was a writer of some skill. She also worked hard at delineated her characters -- doing, to be sure, a lot of telling and not showing. And she did not get deep into their inner life, but at a more superficial level she does good work. I suppose I would say it is quite skilled popular fiction characterization, if not being great literary characterization. Her depiction of Sylvia, in particular, is quite acute, and I believed it utterly. Gay, on the other hand, though a very engaging protagonist, is rather too much the paragon to convince. The book, as I suggested, moves a bit slowly, but it still held my attention. And I will say that I have some interest in checking out something more by Norris (though I probably don't have the TIME to do so!)

Thursday, September 25, 2014

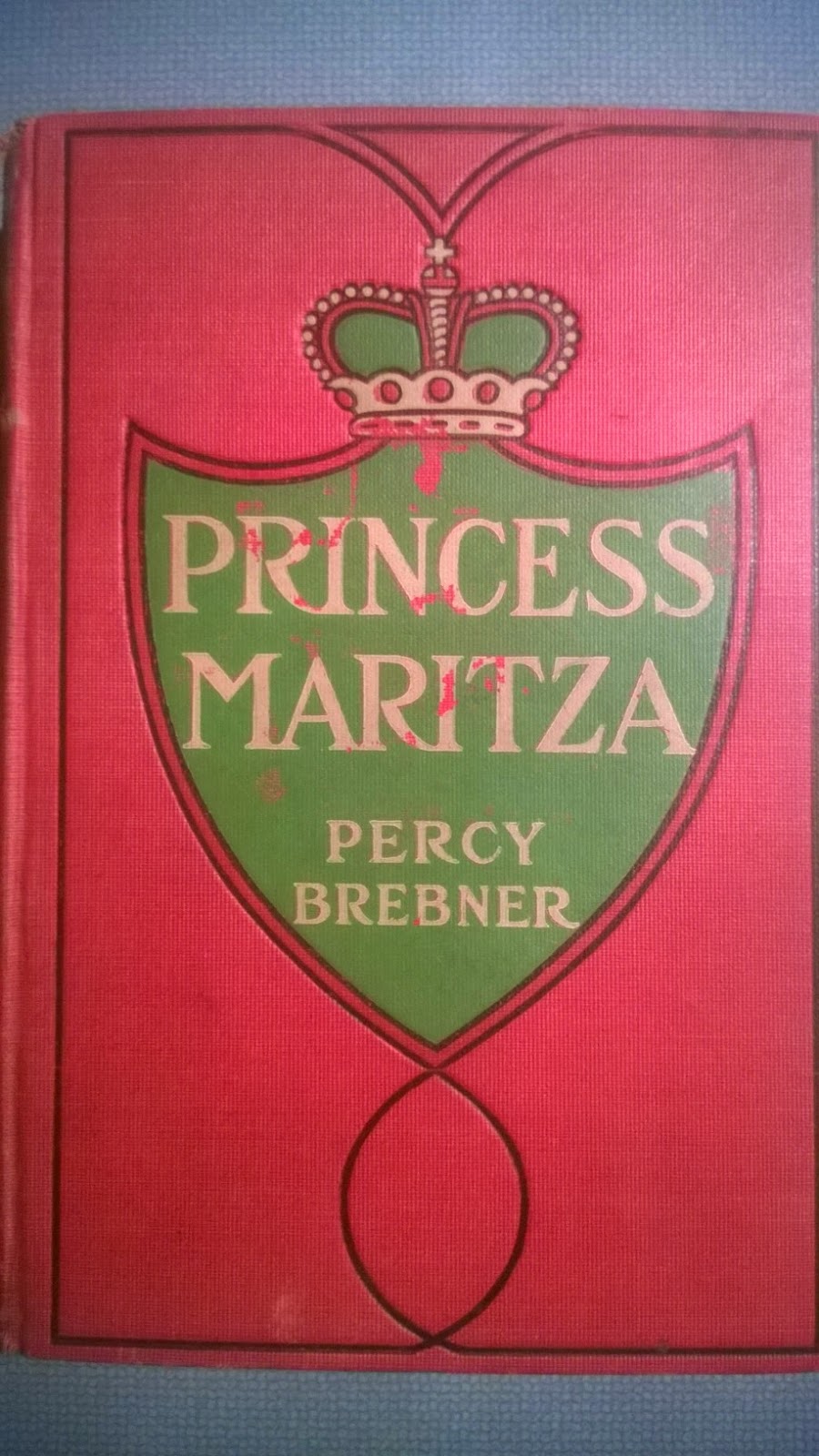

Old Bestsellers: Princess Maritza, by Percy Brebner

Princess Maritza, by Percy Brebner

Princess Maritza, by Percy Brebnera review by Rich Horton

Here's a pretty obscure book, I'd say -- at least to me. I had never heard of the book or the author until I saw it in an antique store just off Highway 55 40 or so miles north of St. Louis. But it was clear that it was a Ruritanian story, and I have a bit of a weakness for that subgenre.

Once again, the best online source of informaton on this non-SF writer was the Science Fiction Encylopedia. Percy James Brebner (1864-1922) was an Englishman. He wrote mostly romantic adventures, at least a dozen novels. Some of his books were written as by "Christian Lys". The SFE is interested in five of his novels that had (mostly somewhat slight) fantastical elements, particularly The Fortress of Yadasara: A Narrative Prepared from the Manuscript of Clinton Verrall, Esq. (in a magazine in 1898 as by Lys, in book form as The Knight of the Silver Star in 1907 as by Brebner) and The Mystery of Ladyplace (1900).

Princess Maritza was first published by T. J. McBride and Son in 1906 according to the copyright notice in my edition, which is a Grosset and Dunlap reprint. (The SFE gives 1907 by Cassell -- perhaps that was the first UK edition?) My edition has two rather nice illustrations by Harrison Fisher, a fairly well-known illustrator of that time, noted in particular for his depictions of women.

As I noted, it's a Ruritanian story, indeed nearly as pure an example as might be found this side of the original, Anthony Hope's The Prisoner of Zenda. Of course it is not nearly as good as that book, but I did rather enjoy it. It opens with the disgraced soldier Desmond Ellery wandering the downs near a friend's house, when he encounters a beautiful 18 year old girl, who tells him that she is playing hooky from the local finishing school ... and also that she is a Princess, though her family's throne, in the apparently Balkan country of Wallaria, has been usurped. Her ambition, though she is but a female, is to return and retake her throne, despite the fact that the Great Powers all oppose this, feeling that Wallaria is best kept in its current state for balance of power reasons. And indeed Desmond's friend Sir Charles Martin informs him later that Princess Maritza's family were terrible rulers.

But Desmond feels there is nothing left for him in England, after he was unfairly dismissed from his military post due to a false story of cheating at cards. So he heads to Sturatzberg, capital of Wallaria, and offers his services to the King. (A curious move, this, as if he was so intrigued by Princess Maritza, why would he swear to serve her enemies?) After a couple of years of no action, he is summoned by a mysterious Frenchman to a meeting with a woman who turns out to be the Queen -- and it seems she will soon have a mission for him, to travel to the secret headquarters of the brigand Vasilici and recruit him to her mission -- which is to rise up and throw out the foreigners who have dominated Wallaria through the weak King. Chief among these seems to be the British Ambassador, Lord Cloverton.

Desmond, in the interim, spends time at court, and becomes associated with the beautiful Countess Frina Mavrodin. Lord Cloverton recognizes Desmond's worth, but is concerned that he will be a problem. Desmond is also kidnapped and brought to a meeting with a masked woman, who warns him against involvement with the Frenchman's schemes ... And there are rumors that Princess Maritza has run away from her English school and returned to Sturatzberg.

Things continue in this vein. Desmond Ellery, torn between his promised service to the Queen and his obsession with the memory of Princess Maritza, dallies with Frina Mavrodin for a while (not realizing her true loyalties) before finally being sent on his mission to Vasilici. He gains a new companion on this trip, a beardless youth who is a brilliant marksman. He learns some of the truth about the scheming Frenchman. There is a duel, and noble men and women are tragically placed on opposite sides of the struggle, and there is a love triangle or quadrangle. Desmond and his loyal servant and the mysterious beardless youth (I defy anyone to guess his identity [grin]) are hopelessly trapped by the brigands in an abandoned castle. The city rises in rebellion ...

Brebner doesn't really miss a trick here. And it mostly works fairly well. It's all quite silly of course, and often implausible, and as with many novels published in this time frame, the shadow of World War I hangs heavily over all the fustian, for a present day reader, anyway. (That said, there is a vein of realpolitik in Brebner's treatment of the place of Wallaria in events of its time.) The ending is, within the constraints of its genre, somewhat believable. The characters are types, of course, but nicely done types -- Desmond is just dense enough to be almost human despite his near-perfection in other aspects; his servant Stephen is an OK comic foil; the Princess is likeable and brave and the tragic Countess is also admirable. The slimy French villain is perhaps a bit too stock and over the top; but what do you expect? The prose is efficient, a bit on the wordy side but not at the expense of readability. Certainly this is not a book that demands revival, but it's still a book I'm happy enough to have encountered.

Friday, September 19, 2014

An Old Fantasy Masterwork: Time and the Gods, by Lord Dunsany

Time and the Gods, by Lord Dunsany

a review by Rich Horton

This probably doesn't really qualify as an old "Bestseller", nor certainly does Dunsany qualify as "forgotten", but these books (six are considered here) were certainly old, and though Dunsany is not forgotten he is perhaps less read these days than he deserves. This is a review first published in 2000 at SF Site, with slight revisions.

Lord Dunsany's full name was Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany (of the Irish peerage). His niece was Lady Violet Powell, nee Pakenham, the wife of the great novelist Anthony Powell and the sister of the notorious Earl of Longford. Lady Violet's memoirs include a depiction of time spent in Lord Dunsany's somewhat old-fashioned Irish home.

Lord Dunsany is widely regarded as a seminal 20th-century writer of fantasy, the originator of many of the tropes we see in story after story, and a master stylist. However, he is not all that widely read any more (or so it seems to me). Speaking for myself, prior to receiving this collection for review (back in 2000), I had read only the odd story or three that I found reprinted in Weird Tales or some anthology. My copy of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy reprint of The King of Elfland's Daughter is still mouldering on a shelf in my basement, shockingly unread. Perhaps I could have been forgiven if I had thought that Dunsany might be more of an "originator" than a "keeper," or that his reputation as a "stylist" might be built on prose more ornate and flowery than is much appreciated these days.

Well, this new collection, the second in Millennium's much to be praised series of Fantasy Masterworks (a companion to their excellent SF Masterworks series), would seem to have been intended to reach readers like me, and to set Dunsany's record straight. And so it does: the best stories in this book are excellent, written in lovely prose that is indeed ornate, but to good effect, often rounded off with an ironic barb, stuffed with lush images, and suffused with the odour of "regret," which Michael Swanwick has called central to "Hard Fantasy." And the bulk of the stories here are excellent or just a step below.

That said, a few caveats are necessary regarding this particular edition. My main issue is with the presentation of the stories. For a major writer like Dunsany, dead these 43 years, I think a collection of this nature should include at least a small amount of critical/biographical/bibliographical apparatus. I'd have liked to see an introduction discussing the history of these stories, and discussing the rest of Dunsany's career. And I'd have liked to see a longer biographical treatment than the brief paragraph on the back cover. (I might also add that there were rather more typos than I like in the stories themselves.) I suppose, however, that we should be happy with any such large collection, and with such a reasonable price as well.

My second caveat is more in the nature of a warning. This book collects Dunsany's first six collections of fantasy stories: The Gods of Pegana, Time and the Gods, The Sword of Welleran and Other Stories, A Dreamer's Tales, The Book of Wonder, and The Last Book of Wonder. For some reason, The Gods of Pegana, Dunsany's first book (1905), is presented last. Time and the Gods, his second book (1906), is presented first. I chose to read the collection in order of writing, and frankly I almost bogged down in the first two books. The Gods of Pegana is a collection of closely linked fragments, dealing almost entirely with the title beings. As an imaginative creation, the book is interesting, but there is no plot, and the "gods" did not come to life for me. Time and the Gods consists of less closely linked stories, but it is still dealing with, essentially, faux "creation myths," and varieties of "Just So Stories." I remained mostly unconvinced. In addition, in these collections Dunsany seemed more prone to his style descending to what might be called "forsoothery," as with so many bad Dunsany imitators. There are a few high points, such as "The Cave of Kai," about a King who wishes to be remembered, "The Relenting of Sarnidac," about a dwarf who is mistaken for a god, and especially the last two stories. "The Dreams of a Prophet" is a brief piece, memorable mainly for a real stinger of a line. "The Journeys of the King" is the longest story in the entire (larger) collection: a moving account of a dying King and the prophets who tell him where he will go on his "last journey."

Thus, I would recommend leaving the two earlier collections until later, or perhaps only sampling them. Dunsany seemed to hit his stride with the remarkable stories in The Sword of Welleran and Other Stories (1908). In these stories the focus is on humans. Also, they incorporate actual plots. There is still the ornate writing, but put to better effect. Furthermore, for all that it is ornate, it is wonderfully balanced. The rhythms, as well as the imagery and the alliteration, are seamless and beautiful. The gods and other odd beings are still present. "The Sword of Welleran" is one of the best, about a once war-like city, now guarded only by the statues of the heroes of its past. Another astounding story is "The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save by Sacnoth," which would be memorable for its glorious title alone. The story itself is a veritable prototype of hundreds of followers in the genre: the land is troubled by an evil wizard who can only be vanquished by a miraculous weapon, the sword Sacnoth, so our hero literally wrests the sword from the spine of an alligator, then sets out on his quest to the "fortress unvanquishable."

The stories continue in similar modes through the rest of the six books included. As time goes on, Dunsany makes connections with Earth more explicit, and by the last couple of books much effort is spent mourning the departure of "Romance," pushed out by modern times, industry and suburbs and so on. (One amusing story, "A Tale of London," turns the tables somewhat, presenting a vision of a marvelous London from the viewpoint of a Sultan's hashish smoker.) Certainly these books were of their time -- just prior to the First World War.

The dominant fantasy landscape here is vaguely Oriental cum Arabic. Much is made of trackless deserts, wondrous cities with their Minarets and Sultans and robed inhabitants, the smoking of hashish, etc. The dominant mood is regret for what is lost or about to be lost. And most of the stories end sadly. The hand of fate lies heavy on the characters herein. The most common length is very short: 1000 to 2000 words or so. But despite the outward sameness, and with the exception of the weaker earlier books, I was not bored with the stories, nor did I feel that Dunsany repeated himself. In fact, taken together the stories gain strength. The collections as a whole are almost stronger than their individual parts: a very rare thing for anthologies.

Perhaps a sample or two of Dunsany's prose would be in order. Here is the opening of "The Fall of Babbulkund":

"I said: 'I will arise now and see Babbulkund, City of Marvel. She is of one age with the Earth, the stars are her sisters. Pharaohs of old time coming conquering from Araby first saw her, a solitary mountain in the desert, and cut the mountain into towers and terraces. They destroyed one of the hills of God, but they made Babbulkund. She is carven, not built, her palaces are one with her terraces, there is neither join nor cleft...'"

From "Poltarnees, Beholder of Ocean":

"Toldees, Mondath, Arizim, these are the Inner Lands, the lands whose sentinels upon their borders do not behold the sea. Beyond them to the East there lies a desert, forever untroubled by man: all yellow it is, and spotted with shadows of stones, and Death is in it, like a leopard lying in the sun. To the south they are bounded by magic, to the west by a mountain, and to the north by the voice and anger of the Polar wind."

Though many of these stories are melancholy, Dunsany is not above dry humour, either the odd dig (on seeing a sheep smoke a pipe: "-- an incident that struck me as unlikely; but in the hills of Sneg I met an honest politician."); or stories with sharply ironic points, or pure entertainments, such as the stories about the pirate Shard, which are among the best collected here ("The Loot of Bombasharna" and "A Story of Land and Sea"). All in all this is as fine an extended collection of fiction as I've seen in a considerable period.

Besides the virtues of the stories themselves, they are significant influences on the fantasy and even the SF of our time. The most obvious derivative works are the many sword and sorcery tales which borrow, too often ineffectively, the quasi-Oriental settings, the quest plots, and broad echoes of Dunsany's prose style. But the influences run elsewhere: certainly Leigh Brackett's Martian landscapes owe something to Dunsany. And even a nominally "hard SF" writer like Arthur C. Clarke (quoted on the back cover calling Dunsany "One of the greatest writers of this century") shows in his romantic visions a distinct heritage from these fantasies.

I recommend this collection of exotic and colourful fantasies to readers interested in the originals from which much contemporary sword and sorcery derive, to those interested in a true master of English prose of the older style, and to those ready to immerse themselves in a melancholy and wholly different world view. Thoroughly involving.

a review by Rich Horton

This probably doesn't really qualify as an old "Bestseller", nor certainly does Dunsany qualify as "forgotten", but these books (six are considered here) were certainly old, and though Dunsany is not forgotten he is perhaps less read these days than he deserves. This is a review first published in 2000 at SF Site, with slight revisions.

Lord Dunsany's full name was Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany (of the Irish peerage). His niece was Lady Violet Powell, nee Pakenham, the wife of the great novelist Anthony Powell and the sister of the notorious Earl of Longford. Lady Violet's memoirs include a depiction of time spent in Lord Dunsany's somewhat old-fashioned Irish home.

Lord Dunsany is widely regarded as a seminal 20th-century writer of fantasy, the originator of many of the tropes we see in story after story, and a master stylist. However, he is not all that widely read any more (or so it seems to me). Speaking for myself, prior to receiving this collection for review (back in 2000), I had read only the odd story or three that I found reprinted in Weird Tales or some anthology. My copy of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy reprint of The King of Elfland's Daughter is still mouldering on a shelf in my basement, shockingly unread. Perhaps I could have been forgiven if I had thought that Dunsany might be more of an "originator" than a "keeper," or that his reputation as a "stylist" might be built on prose more ornate and flowery than is much appreciated these days.

Well, this new collection, the second in Millennium's much to be praised series of Fantasy Masterworks (a companion to their excellent SF Masterworks series), would seem to have been intended to reach readers like me, and to set Dunsany's record straight. And so it does: the best stories in this book are excellent, written in lovely prose that is indeed ornate, but to good effect, often rounded off with an ironic barb, stuffed with lush images, and suffused with the odour of "regret," which Michael Swanwick has called central to "Hard Fantasy." And the bulk of the stories here are excellent or just a step below.

That said, a few caveats are necessary regarding this particular edition. My main issue is with the presentation of the stories. For a major writer like Dunsany, dead these 43 years, I think a collection of this nature should include at least a small amount of critical/biographical/bibliographical apparatus. I'd have liked to see an introduction discussing the history of these stories, and discussing the rest of Dunsany's career. And I'd have liked to see a longer biographical treatment than the brief paragraph on the back cover. (I might also add that there were rather more typos than I like in the stories themselves.) I suppose, however, that we should be happy with any such large collection, and with such a reasonable price as well.

My second caveat is more in the nature of a warning. This book collects Dunsany's first six collections of fantasy stories: The Gods of Pegana, Time and the Gods, The Sword of Welleran and Other Stories, A Dreamer's Tales, The Book of Wonder, and The Last Book of Wonder. For some reason, The Gods of Pegana, Dunsany's first book (1905), is presented last. Time and the Gods, his second book (1906), is presented first. I chose to read the collection in order of writing, and frankly I almost bogged down in the first two books. The Gods of Pegana is a collection of closely linked fragments, dealing almost entirely with the title beings. As an imaginative creation, the book is interesting, but there is no plot, and the "gods" did not come to life for me. Time and the Gods consists of less closely linked stories, but it is still dealing with, essentially, faux "creation myths," and varieties of "Just So Stories." I remained mostly unconvinced. In addition, in these collections Dunsany seemed more prone to his style descending to what might be called "forsoothery," as with so many bad Dunsany imitators. There are a few high points, such as "The Cave of Kai," about a King who wishes to be remembered, "The Relenting of Sarnidac," about a dwarf who is mistaken for a god, and especially the last two stories. "The Dreams of a Prophet" is a brief piece, memorable mainly for a real stinger of a line. "The Journeys of the King" is the longest story in the entire (larger) collection: a moving account of a dying King and the prophets who tell him where he will go on his "last journey."

Thus, I would recommend leaving the two earlier collections until later, or perhaps only sampling them. Dunsany seemed to hit his stride with the remarkable stories in The Sword of Welleran and Other Stories (1908). In these stories the focus is on humans. Also, they incorporate actual plots. There is still the ornate writing, but put to better effect. Furthermore, for all that it is ornate, it is wonderfully balanced. The rhythms, as well as the imagery and the alliteration, are seamless and beautiful. The gods and other odd beings are still present. "The Sword of Welleran" is one of the best, about a once war-like city, now guarded only by the statues of the heroes of its past. Another astounding story is "The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save by Sacnoth," which would be memorable for its glorious title alone. The story itself is a veritable prototype of hundreds of followers in the genre: the land is troubled by an evil wizard who can only be vanquished by a miraculous weapon, the sword Sacnoth, so our hero literally wrests the sword from the spine of an alligator, then sets out on his quest to the "fortress unvanquishable."

The stories continue in similar modes through the rest of the six books included. As time goes on, Dunsany makes connections with Earth more explicit, and by the last couple of books much effort is spent mourning the departure of "Romance," pushed out by modern times, industry and suburbs and so on. (One amusing story, "A Tale of London," turns the tables somewhat, presenting a vision of a marvelous London from the viewpoint of a Sultan's hashish smoker.) Certainly these books were of their time -- just prior to the First World War.

The dominant fantasy landscape here is vaguely Oriental cum Arabic. Much is made of trackless deserts, wondrous cities with their Minarets and Sultans and robed inhabitants, the smoking of hashish, etc. The dominant mood is regret for what is lost or about to be lost. And most of the stories end sadly. The hand of fate lies heavy on the characters herein. The most common length is very short: 1000 to 2000 words or so. But despite the outward sameness, and with the exception of the weaker earlier books, I was not bored with the stories, nor did I feel that Dunsany repeated himself. In fact, taken together the stories gain strength. The collections as a whole are almost stronger than their individual parts: a very rare thing for anthologies.

Perhaps a sample or two of Dunsany's prose would be in order. Here is the opening of "The Fall of Babbulkund":

"I said: 'I will arise now and see Babbulkund, City of Marvel. She is of one age with the Earth, the stars are her sisters. Pharaohs of old time coming conquering from Araby first saw her, a solitary mountain in the desert, and cut the mountain into towers and terraces. They destroyed one of the hills of God, but they made Babbulkund. She is carven, not built, her palaces are one with her terraces, there is neither join nor cleft...'"

From "Poltarnees, Beholder of Ocean":

"Toldees, Mondath, Arizim, these are the Inner Lands, the lands whose sentinels upon their borders do not behold the sea. Beyond them to the East there lies a desert, forever untroubled by man: all yellow it is, and spotted with shadows of stones, and Death is in it, like a leopard lying in the sun. To the south they are bounded by magic, to the west by a mountain, and to the north by the voice and anger of the Polar wind."

Though many of these stories are melancholy, Dunsany is not above dry humour, either the odd dig (on seeing a sheep smoke a pipe: "-- an incident that struck me as unlikely; but in the hills of Sneg I met an honest politician."); or stories with sharply ironic points, or pure entertainments, such as the stories about the pirate Shard, which are among the best collected here ("The Loot of Bombasharna" and "A Story of Land and Sea"). All in all this is as fine an extended collection of fiction as I've seen in a considerable period.

Besides the virtues of the stories themselves, they are significant influences on the fantasy and even the SF of our time. The most obvious derivative works are the many sword and sorcery tales which borrow, too often ineffectively, the quasi-Oriental settings, the quest plots, and broad echoes of Dunsany's prose style. But the influences run elsewhere: certainly Leigh Brackett's Martian landscapes owe something to Dunsany. And even a nominally "hard SF" writer like Arthur C. Clarke (quoted on the back cover calling Dunsany "One of the greatest writers of this century") shows in his romantic visions a distinct heritage from these fantasies.

I recommend this collection of exotic and colourful fantasies to readers interested in the originals from which much contemporary sword and sorcery derive, to those interested in a true master of English prose of the older style, and to those ready to immerse themselves in a melancholy and wholly different world view. Thoroughly involving.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

Old Bestsellers: The Man from Scotland Yard, by David Frome

The Man from Scotland Yard, by David Frome

The Man from Scotland Yard, by David Fromea review by Rich Horton

This book might not have been a real bestseller but it seemed to do OK: the edition I have was the fifth printing (in about a year) of the Pocket Books edition. Indeed, its publication history is interesting (to me), and a bit of a window on publishing history in general.

The first edition, in 1932 was from Farrar and Rinehart. This company was founded in 1929 by John C. Farrar and Stanley Rinehart, Jr. This was the first of two prominent publishing firms founded by Farrar -- the second of course is the legendary Farrar, Straus and Giroux, founded as Farrar, Straus in 1946. Stanley Rinehart was the son of famous mystery writer Mary Roberts Rinehart. He and his brother Frederick had worked at the firm George H. Doran (which published the last book I reviewed, You Know Me Al, by Ring Lardner), but which became Doubleday, Doran after a merger in 1927. Stanley and Frederick then joined Farrar in his new venture, taking their mother and her future books with them. After Farrar left Farrar and Rinehart, the company was called Rinehart and Company until 1960, when a merger with two other companies, Henry Holt and John C. Winston, created the prominent firm Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

There were no mass market paperbacks in the early '30s, so the first inexpensive edition of The Man from Scotland Yard was a hardcover from Grosset and Dunlap in 1934, one of the (perhaps THE) leading reprint hardcover houses. The mass market paperback was essentially invented by Pocket Books in 1939, so this book, first reprinted in paperback in 1942, was a fairly early example. And my edition, I should add, was a wartime edition, and the publishers made special note of that, with this disclaimer: "In order to cooperate with the government's war effort, this book has been made in strict conformity with WPB regulations concerning the use of certain materials." There is also a sort of PSA at the end urging people to "HELP WIN THE WAR! Don't waste anything."

As for the author, "David Frome" has a somewhat interesting history. Frome was a pseudonym for an American writer with the unlikely name of Zenith Brown (nee Jones). Zenith Brown was born in California (daughter of a missionary to Indians), and was educated at the University of Washington (in Seattle), and briefly taught there, but lived much of her life in Annapolis. Her husband, Ford K. Brown, was a Professor at the very well regarded liberal arts school St. John's College in Annapolis: known primarily for their "Great Books" curriculum. Zenith Brown (1898-1983) published her first novel in 1929, when she was living in London: In at the Death, as by Frome. Her English-set books continued to be published under the Frome name, but she also wrote a great many mysteries set in the US (mainly in the DC area) as by "Leslie Ford", and also a few books as by "Brenda Conrad". As "Leslie Ford" she was apparently a regular in the Saturday Evening Post. She stopped writing )or at least publishing) in 1962.

Well, after all that blather, what was the book like? I quite enjoyed it. It's billed as "A Mr. Pinkerton Mystery", as were most or all of her British-set books. Mr. Pinkerton is a mousy Welsh widower, free at last from the domination of his horrible wife, but with nothing in his life except his (apparently accidental) friendship with Inspector J. Humphrey Bull of Scotland Yard. Pinkerton is not really central to the book, though he's an important character. The story is told from multiple points of view, but Bull's POV is most important.

It opens with a pair of young men noticing an acquaintance of theirs, the somewhat older (but still beautiful) Diana Barrett, looking distressed and heading to a moneylenders'. It seems she is known as a reckless gambler on horse racing. And indeed Mrs. Barrett is next seen begging Mr. David Craikie for extra time to pay back her £5000 loan. But it seems she must ask David's brother Simon instead, and he is not in. Then we meet handwriting expert Mr. Arthurington, returning from holiday in France. When Mr. Arthurington gets home, he is shocked to discover a dead man in his house, which had been rented but (mysteriously?) vacated a short time previously. Next up is Inspector Bull, looking into the matter of an odd note claiming "a mother and three little ones" have been killed and buried in the back garden of a small house ... only to find that the murdered creatures are cats. And finally we meet Mr. Arthurington's daughter Joan and her friend Nancy, also returning to England in the company of their duenna, Miss Mandle.

All this seems terribly complicated, and it is. Before long another murder has occurred, and Inspector Bull is on the case, soon realizing that -- perhaps -- the two murdered men are in fact the moneylenders Simon and David Craikie. Or are they? The two brothers were reclusive people, and the identification doesn't seem absolutely certain. Mr. Pinkerton shows up begging to help, and to get him out of his hair Bull asks him to investigate the matter of the murdered cats ... and somehow Pinkerton, largely by accident, finds out, or helps Bull find out, and unexpected connection between that disquieting but trivial incident and the double murder. As for all the other characters ... Mrs. Barrett, the Arhuringtons, even the two young men in the opening scene ... they are all connected to each other -- mostly they are neighbors, and indeed they also have at least slight connections to the Craikies, or to the Craikies' lawyer.

Complications build on complications. There is a Craikie sister and a (missing) Craikie daughter. The Australian tenant of the Arthurington house might be implicated. Social climbing Americans are mentioned. Mr. Arthurington's handwriting expertise comes into play. And Mr. Pinkerton goes off to Liverpool ...

The whole construction is highly improbable and overcomplicated, but it does pretty much hold together, and it makes for a satisfyingly intricate mystery with a fairly believable solution (believable under the implicit conditions of this subgenre). Inspector Bull is an pretty well-realized, if somewhat stock, character, and enjoyable to read about. There are moments of suspense and danger, and the book is always readable and interesting. It's far from a great work -- it's an artificial construction. But on its own terms it's quite fun. Edmund Wilson (not a favorite of mine ... wrong about Lovecraft, wrong about Tolkien, wrong about entertainment in general -- though to be fair, pretty much right about the likes of Nabokov and Hemingway and Fitzgerald) famously asked "Who cares who killed Roger Ackroyd?", and of course that's a classic case of entirely missing the point. No, we don't really "care" about Ackroyd -- or, in this book, the Craikies -- in any deep way: the pleasures are different and doubtless shallower, but this sort of book does what it does (when done well) effectively.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)