Richard A. Lovett is one of Analog's most regular contributors (of non-fiction as well as fiction), and one of its best. Today is his 65th birthday, and so here is a compilations of many of my Locus reviews of his stories.

(Locus, March 2003)

More interesting in the March issue of Analog is Richard A. Lovett's "Equalization", which addresses an elaborate version of the idea at the heart of Kurt Vonnegut's classic "Harrison Bergeron". In Lovett's story, people choose a career in early adolescence, and from that point forward they are transferred to new bodies each year. The idea is to balance skilled minds with less-skilled bodies, so that competition within a field is roughly equal. The story itself concerns a long-distance runner who realizes that he has been, presumably by mistake, transferred to his own original body, giving him a huge advantage. The idea here is quite interesting, but the story itself doesn't quite work, and the full ramifications of the central idea don't really hold together.

(Locus, September 2003)

The September Analog's strongest story is Richard Lovett's "Tiny Berries", which postulates even worse spam than now -- to the point of intercepting cars and extorting sales. The hero and a couple of friends come up with a solution (probably not workable but interesting) -- wrapped around a sweet but not really convincing love story.

(Locus, January 2004)

Richard A. Lovett's "Weapons of Mass Distraction" (Analog, January-February) extrapolates Patriot Act-like anti-terrorist measures to extremes, making a point about the real consequences -- and one beneficiary -- of such invasions of privacy.

(Locus, June 2005)

Richard Lovett and Mark Niemann-Ross in "NetPuppets" (Analog, June 2005) posit a Sims-like online game. A group of co-workers discover the game and create a couple of characters. The game adds detail to the characters, sometimes making subtle changes. The players try to alter their characters' lives, but unlike with Sims their actions are constrained to fairly plausible real-life actions -- for example, they cannot make a character win the lottery, but they can push her towards a better job. But they might also push their characters in negative ways -- or in criminal ways. But so what? It's only a game, right? The twist is predictable but well-handled, and the moral point, expressed through several characters, is sharply put.

(Locus, November 2005)

I also liked Richard A. Lovett’s "911-Backup", which as with many of Lovett’s stories deals intelligently with the problem areas of future tech, in ideal Analog fashion. In this case the tech is brain capacity enhancement via computer implant, and the problem is "What happens if the computer crashes, and you have offloaded too much capacity away from your brain onto the computer?"

(Locus, February 2007)

Richard A. Lovett’s "The Unrung Bells of the Marie Celeste" (Analog, January-February), is an interesting look at an idea I’ve seen once or twice before: FTL that works fine for unmanned missions but that fails whenever a human is the pilot. (For example, the fairly obscure Poul Anderson story "Mustn’t Touch".) Lovett’s reason why it doesn’t work is clever and also leads to an interesting personal story about his main character, a man chosen for a test flight because he is suicidal.

(Locus, October 2009)

Abyss and Apex for the third quarter includes a Richard A. Lovett story, "Carpe Mañana", that, as often with Lovett, thoroughly explores the social implications of a technological innovation -- his work in this vein reminds me of H. L. Gold’s Galaxy more than about any contemporary writer I can recall. The innovation explored here is the stasis box -- a fairly old SF idea, a box in which no time passes. It’s first used for food preservation -- no need for refrigeration if you can just pop in the fresh food and use it when needed. But Lovett, in a series of short pieces, shows its use by humans -- a daughter trying to escape contact with her parents, a man with Seasonal Affective Disorder skipping winter, prisoners warehoused until their cases are decided, etc. It’s thoughtful and often scary.

(Locus, July 2011)

I mentioned Jack and the Beanstalk stories last month and look! This month Analog has one. in the July-August 2011 issue. It’s called "Jak and the Beanstalk", by Richard A. Lovett, and I don’t think it will surprise anyone to learn that the Beanstalk of the title is a space elevator. Jak spends his life planning to climb the Beanstalk, a rather mad enterprise, and the first part of the story is devoted to showing how one might do that ... which to be honest isn’t terribly compelling as narrative. But the story gets rather better when war breaks out while Jak is on his way up -- making his position on the Beanstalk arguably better than anyone’s on Earth. And when he gets to the geosynchronous part of the Beanstalk and finds the maintenance crew attempting to survive, his priorities change -- in a way he finally really grows up, and ends up heading elsewhere. Lovett is probably Analog’s best current regular writer -- a writer who fits snugly within the Analog format yet does thought-provoking and interesting and continually different work within it.

(Locus, August 2012)

At the July/August Analog the cover story is "Nightfall on the Peak of Eternal Light", by Richard Lovett and William Gleason, a Moon colonization story. It focuses on a man trying to immigrate to the Moon, as part of a witness protection program. The problem is, it's hard to earn your ticket to stay ... not to mention, it turns out to be easy enough to be found even if you do stay. The ideas about why and how the Moon might be colonized are interesting, and the central plot is enjoyable enough, though the story is probably a bit too long.

(Locus, February 2015)

Analog's big Double Issue for January-February features "Defender of Worms", a novella from Richard Lovett, the latest in a long series of stories about an AI named Brittney. Freed by her first owner, who lives in the outer Solar System, she is back on Earth and acting as a sort of governess for a rebellious rich girl named Memphis. But Brittney is being hunted by another AI, which she calls the Others, and Memphis wants to escape her mother's influence, so the two have lit out for the desolate American West, off the grid. But the enemy has resources, and Memphis has a lot of learning to do, besides Brittney needing to learn to live with Memphis. This is good, entertaining SF, with plenty of action and some nice (if not terribly new) ideas behind it.

Sunday, October 28, 2018

Ace Double Reviews, 14: Cosmic Checkmate, by Charles V. De Vet and Katherine MacLean/King of the Fourth Planet, by Robert Moore Williams

Ace Double Reviews, 14: Cosmic Checkmate, by Charles V. De Vet and Katherine MacLean/King of the Fourth Planet, by Robert Moore Williams (#F-149, 1962, $0.40)

On what would have been Charles V. De Vet's 107th birthday, I'm reposting one of my personal favorites among my Ace Double reviews -- not because the books are my favorites, but because I had a lots of fun tracking down the extended history of the De Vet/MacLean novel and its sequel.

King of the Fourth Planet is about 43,000 words long. Cosmic Checkmate is about 33,000 words, and it has a complicated publishing history. It's an expansion (by a factor of roughly 2) of the novelette "Second Game" (Astounding, March 1958), a Hugo nominee and still a fairly well-known story. The novel was reissued in 1981 by DAW with further expansions, to some 56,000 words, now retitled Second Game after the novelette. (A much better title!) Finally, De Vet by himself wrote a sequel published in the February 1991 Analog, called "Third Game".

Neither of the authors of Cosmic Checkmate was terribly prolific, indeed, their quantity of output is strikingly similar: 30 or 40 stories and one solo novel each. De Vet (1911-1997) began publishing in 1950, and through 1962 published a couple of dozen stories. Over the next couple of decades he published far less often, just 8 more stories according to the ISFDB, several in Ted White's mid-70s Amazing, with "Third Game" his last story. He published just one additional novel, Special Feature (1975), another expansion of a 1958 Astounding novelette ("Special Feature", May 1958). MacLean (b. 1925), is deservedly the better known. She is this year's SFWA Writer Emeritus (2003). She began publishing in 1949, and has had a story in Analog as recently as "Kiss Me" (February 1997), which made the Hartwell Year's Best #3. Her best-known story is almost certainly "The Missing Man" (Analog, March 1971), which won a Nebula for Best Novella, and which was expanded to her only solo novel, Missing Man (1975). (She has published one other collaborative novel, Dark Wing, (1979), with Carl West, which I haven't seen but which appears to be a YA Fantasy.) Other stories such as "Contagion" (1950), "Pictures Don't Lie" (1951), "The Snowball Effect" (1952), "The Diploids" (1953), "The Trouble With You Earth People" (1968), and "The Kidnapping of Baroness 5" (1995), gained considerable notice.

Robert Moore Williams (1907-1977) was a fairly regular writer for the SF magazines beginning in the late 30s, and ending in 1965-1966 with a sudden spurt of 4 stories for Fred Pohl's If after roughly a decade of publishing no short fiction. He also published quite a few novels in the field, including 11 Ace Double halves (in 9 books -- two of his halves were story collections that backed his own novels). Based on what I've read of his work, he wasn't really very good, and presumably as a result he is all but forgotten now. He might have been best known for a series of Edgar Rice Burroughs-like stories about heroes named Zanthar and Jongor, which appeared from Lancer and Popular Library from 1966 through 1970. (The Jongor books were reprints (perhaps expanded) of stories from Fantastic Adventures between 1940 and 1951, and the 1970 editions had Frazetta covers, which I am pretty sure I saw back in the day, though I never read them.)

King of the Fourth Planet is pretty straightforward SF. John Rolf is a former executive of the Company for Planetary Development who has repented of his unethical ways, and moved to Mars, divorcing his wife and leaving her with their young daughter when she refuses to accompany him. Rolf lives on the giant mountain Suzusilam, where most of the Martians live. The mountain (perhaps a "prediction" of Olympus Mons, which wasn't discovered until 1971) is divided into seven levels, on each of which live Martians of increasing "civilizedness". The fourth level is the home of the Martians at roughly Earth levels of development. The seventh level is reputedly home only to the mysterious King of the Red Planet, a Martian of incredible powers who "holds the mountain in his hand". Rolf lives on the fourth level, home to many mechanical geniuses, and he himself is working on a telepathy machine, which he hopes will solve humanity's problems by giving all people understanding of others. He is assisted at times by his friend Thallen from the fifth level. Just as he completes his machine, a Human spaceship lands, and Rolf senses the evil mind of the Company executive controlling the spaceship. Before you know it, this man, Jim Hardesty, shows up at Rolf's doorstep, demanding his assistance in cheating the Martians. Rolf refuses, whereupon Hardesty reveals that he has hired Rolf's daughter as his secretary (i.e. potential sex slave), but Rolf, with his daughter's help, continues to refuse. Soon a man shows up who has fallen in love with Rolf's daughter, but then Hardesty mounts an attack on the Martians, the daughter is kidnapped, Rolf is injured and his mind becomes detached from his body, and all leads to a confrontation on the seventh level with the mysterious King.

It's mostly a pretty bad book. Some of it is slapdash, such as having people run up and down this presumably huge mountain in no more than a couple of hours. The action develops too quickly, and not logically, and plot threads and ideas that showed promise (or not) are often as not brushed aside without resolution, or with unsatisfactory resolution. There are some nice bits -- the climactic scene at the top of the mountain is pretty impressive in parts, the advanced Martian tech represented by "abacuses" that play musical notes which cause healing and other powers is really kind of nicely depicted, the ethical message advanced, if crudely put, seems deeply felt and not unreasonable. Still -- not really a book worth attention. And not any reason to reconsider Williams' place in the canon.

Second Game is rather better. It's the story of the planet Velda, which has just been discovered by the Earth-centered Ten Thousand Worlds. After warning that they wanted no contact, the Veldians destroyed the Fleet that Earth sent anyway. The narrator, a chess champion, has learned that the Veldians base their society around proficiency in a Game, somewhat like Chess but more complicated. (Details are sketchy, but it is played on a 13x13 board, and each player controls 26 pieces, or "pukts".) Equipped with an "annotator", sort of an AI addition to his brain, the narrator learns the Game and comes to Velda to challenge all comers. He puts up a sign saying "I'll beat you the Second Game". And after probing the opponents' weaknesses by playing the first game, he does indeed beat them the second time. He finally draws the attention of Kalin Trobt, a high official and thus a proficient Game player. After the most difficult Game yet, the narrator again prevails, but Trobt perceives that he is a human, and arrests him as a spy.

Veldian society is predicated on exaggerated concepts of honor, and on absolute honesty. So the narrator is simply placed under house arrest at Trobt's house, though he is told that he will die, in the "Final Game". Over the next couple of weeks, the narrator and Trobt become friends, but the narrator's fate remains sealed. Both probe each other for secrets about their respective societies, and in particular a biological reason for much of the Veldian situation is revealed. Finally the narrator comes up with a surprising solution to his problem, and to Velda's problem, and eventually to the Ten Thousand Worlds' problem.

This short novel is a quick, entertaining, and generally absorbing read. It's not quite convincing -- the Game is marginally plausible, but not the narrator's proficiency. The Veldian social structure, and military prowess, both seem rather artificial. I didn't quite buy the biological problem at the heart of Veldian society either. Indeed, Veldqan biology as portrayed seems truly implausible -- I can't believe this race would survive! Other problems were lesser, such as the magical ability of Veldians and Humans to interbreed (this problem could easily have been finessed by a reference to panspermia or a lost colony or something, but instead the Veldians are supposed to be true aliens). Still, overall the story is enjoyable and thoughtful.

I read the novelette "Second Game" and the novel Cosmic Checkmate back to back. It's interesting how closely they resemble each other. The novel is not an extension, but an organic expansion, without even much in the way of added subplots. There is a somewhat unconvincing love interest for the narrator in the novel which is absent in the novelette.* Otherwise the expansions are all fleshed out scenes, added explanations. I think it actually works pretty well -- the novel does not seem padded.

I followed this by reading the 1981 DAW novel, Second Game. This is longer still, and it also features some curious changes. The changes include: changing the planet's name from Velda to Veldq (presumably to make it more "alien", and also perhaps to avoid sounding like a woman's name), changing the narrator's name from Robert O. Lang to Leonard Stromberg (a change I utterly fail to understand unless perhaps that was the original name, and John Campbell insisted on a more Anglo-Saxon lead character), and adding a new social group to Veldq society, the Kismans, low-status merchants. Further changes include more bald exposition of the Ten Thousand Worlds' situation, an altered (and not terribly believable) explanation for the Veldqan level of technology, a hugely expanded subplot about the narrator's Veldqan love interest, including some rather embarrassing sex scenes (and a revised account of the relationship of the sexes on Veldq), and a fair amount of small interpolations, fleshing out details.

On balance I think I prefer the shorter 1962 novel to the 1981 expansion: some of the 1981 additions are sensible fleshing out, but some are silly. The expanded love story is logical and fills in something missing in the 1962 version, but it's not very well done. Other additions, such as the Kismans and the new explanation of Veldqan tech, seem either superfluous or wrong. I wouldn't say, however, that the 1981 version feels padded -- the novelette, in retrospect, seems somewhat rushed, and I would have to say the story basically supports at least 50,000 words.

Finally I went ahead and read the 1991 novelette sequel, by De Vet alone, "Third Game". This is about 15,000 words long. It's set 23 years after the main action of Second Game. There are severe social problems on Veldq, and Leonard Stromberg's half-Veldqan son, Kalin Stromberg, comes to the planet to try to help. After some more harsh evidence of the silly over-violent Veldqan society, and another sometimes embarrassing highly sexed romance, which involved dealing fairly with the oppressed Kisman minority**, and, get this (shades of Asimov's The Stars Like Dust) -- adopt a constitution modelled on the US constitution. It's really a very bad story.

(*There was a curious brief mention of the girl who becomes the narrator's love interest in the novelette -- on reading that, bells went off in my head, and I was surprised that she did not reappear in the story. Which makes me wonder if the novelette wasn't cut before publication, as opposed to the novel being a later expansion.)

(**The Kismans are important in this story as they weren't in the 1981 Second Game, making me wonder if De Vet hadn't already written a version of "Third Game" when he (and MacLean) expanded Cosmic Checkmate to Second Game.)

On what would have been Charles V. De Vet's 107th birthday, I'm reposting one of my personal favorites among my Ace Double reviews -- not because the books are my favorites, but because I had a lots of fun tracking down the extended history of the De Vet/MacLean novel and its sequel.

King of the Fourth Planet is about 43,000 words long. Cosmic Checkmate is about 33,000 words, and it has a complicated publishing history. It's an expansion (by a factor of roughly 2) of the novelette "Second Game" (Astounding, March 1958), a Hugo nominee and still a fairly well-known story. The novel was reissued in 1981 by DAW with further expansions, to some 56,000 words, now retitled Second Game after the novelette. (A much better title!) Finally, De Vet by himself wrote a sequel published in the February 1991 Analog, called "Third Game".

|

| (Covers by Ed Emswhiller and Ed Valigursky) |

Neither of the authors of Cosmic Checkmate was terribly prolific, indeed, their quantity of output is strikingly similar: 30 or 40 stories and one solo novel each. De Vet (1911-1997) began publishing in 1950, and through 1962 published a couple of dozen stories. Over the next couple of decades he published far less often, just 8 more stories according to the ISFDB, several in Ted White's mid-70s Amazing, with "Third Game" his last story. He published just one additional novel, Special Feature (1975), another expansion of a 1958 Astounding novelette ("Special Feature", May 1958). MacLean (b. 1925), is deservedly the better known. She is this year's SFWA Writer Emeritus (2003). She began publishing in 1949, and has had a story in Analog as recently as "Kiss Me" (February 1997), which made the Hartwell Year's Best #3. Her best-known story is almost certainly "The Missing Man" (Analog, March 1971), which won a Nebula for Best Novella, and which was expanded to her only solo novel, Missing Man (1975). (She has published one other collaborative novel, Dark Wing, (1979), with Carl West, which I haven't seen but which appears to be a YA Fantasy.) Other stories such as "Contagion" (1950), "Pictures Don't Lie" (1951), "The Snowball Effect" (1952), "The Diploids" (1953), "The Trouble With You Earth People" (1968), and "The Kidnapping of Baroness 5" (1995), gained considerable notice.

Robert Moore Williams (1907-1977) was a fairly regular writer for the SF magazines beginning in the late 30s, and ending in 1965-1966 with a sudden spurt of 4 stories for Fred Pohl's If after roughly a decade of publishing no short fiction. He also published quite a few novels in the field, including 11 Ace Double halves (in 9 books -- two of his halves were story collections that backed his own novels). Based on what I've read of his work, he wasn't really very good, and presumably as a result he is all but forgotten now. He might have been best known for a series of Edgar Rice Burroughs-like stories about heroes named Zanthar and Jongor, which appeared from Lancer and Popular Library from 1966 through 1970. (The Jongor books were reprints (perhaps expanded) of stories from Fantastic Adventures between 1940 and 1951, and the 1970 editions had Frazetta covers, which I am pretty sure I saw back in the day, though I never read them.)

King of the Fourth Planet is pretty straightforward SF. John Rolf is a former executive of the Company for Planetary Development who has repented of his unethical ways, and moved to Mars, divorcing his wife and leaving her with their young daughter when she refuses to accompany him. Rolf lives on the giant mountain Suzusilam, where most of the Martians live. The mountain (perhaps a "prediction" of Olympus Mons, which wasn't discovered until 1971) is divided into seven levels, on each of which live Martians of increasing "civilizedness". The fourth level is the home of the Martians at roughly Earth levels of development. The seventh level is reputedly home only to the mysterious King of the Red Planet, a Martian of incredible powers who "holds the mountain in his hand". Rolf lives on the fourth level, home to many mechanical geniuses, and he himself is working on a telepathy machine, which he hopes will solve humanity's problems by giving all people understanding of others. He is assisted at times by his friend Thallen from the fifth level. Just as he completes his machine, a Human spaceship lands, and Rolf senses the evil mind of the Company executive controlling the spaceship. Before you know it, this man, Jim Hardesty, shows up at Rolf's doorstep, demanding his assistance in cheating the Martians. Rolf refuses, whereupon Hardesty reveals that he has hired Rolf's daughter as his secretary (i.e. potential sex slave), but Rolf, with his daughter's help, continues to refuse. Soon a man shows up who has fallen in love with Rolf's daughter, but then Hardesty mounts an attack on the Martians, the daughter is kidnapped, Rolf is injured and his mind becomes detached from his body, and all leads to a confrontation on the seventh level with the mysterious King.

It's mostly a pretty bad book. Some of it is slapdash, such as having people run up and down this presumably huge mountain in no more than a couple of hours. The action develops too quickly, and not logically, and plot threads and ideas that showed promise (or not) are often as not brushed aside without resolution, or with unsatisfactory resolution. There are some nice bits -- the climactic scene at the top of the mountain is pretty impressive in parts, the advanced Martian tech represented by "abacuses" that play musical notes which cause healing and other powers is really kind of nicely depicted, the ethical message advanced, if crudely put, seems deeply felt and not unreasonable. Still -- not really a book worth attention. And not any reason to reconsider Williams' place in the canon.

Second Game is rather better. It's the story of the planet Velda, which has just been discovered by the Earth-centered Ten Thousand Worlds. After warning that they wanted no contact, the Veldians destroyed the Fleet that Earth sent anyway. The narrator, a chess champion, has learned that the Veldians base their society around proficiency in a Game, somewhat like Chess but more complicated. (Details are sketchy, but it is played on a 13x13 board, and each player controls 26 pieces, or "pukts".) Equipped with an "annotator", sort of an AI addition to his brain, the narrator learns the Game and comes to Velda to challenge all comers. He puts up a sign saying "I'll beat you the Second Game". And after probing the opponents' weaknesses by playing the first game, he does indeed beat them the second time. He finally draws the attention of Kalin Trobt, a high official and thus a proficient Game player. After the most difficult Game yet, the narrator again prevails, but Trobt perceives that he is a human, and arrests him as a spy.

Veldian society is predicated on exaggerated concepts of honor, and on absolute honesty. So the narrator is simply placed under house arrest at Trobt's house, though he is told that he will die, in the "Final Game". Over the next couple of weeks, the narrator and Trobt become friends, but the narrator's fate remains sealed. Both probe each other for secrets about their respective societies, and in particular a biological reason for much of the Veldian situation is revealed. Finally the narrator comes up with a surprising solution to his problem, and to Velda's problem, and eventually to the Ten Thousand Worlds' problem.

This short novel is a quick, entertaining, and generally absorbing read. It's not quite convincing -- the Game is marginally plausible, but not the narrator's proficiency. The Veldian social structure, and military prowess, both seem rather artificial. I didn't quite buy the biological problem at the heart of Veldian society either. Indeed, Veldqan biology as portrayed seems truly implausible -- I can't believe this race would survive! Other problems were lesser, such as the magical ability of Veldians and Humans to interbreed (this problem could easily have been finessed by a reference to panspermia or a lost colony or something, but instead the Veldians are supposed to be true aliens). Still, overall the story is enjoyable and thoughtful.

I read the novelette "Second Game" and the novel Cosmic Checkmate back to back. It's interesting how closely they resemble each other. The novel is not an extension, but an organic expansion, without even much in the way of added subplots. There is a somewhat unconvincing love interest for the narrator in the novel which is absent in the novelette.* Otherwise the expansions are all fleshed out scenes, added explanations. I think it actually works pretty well -- the novel does not seem padded.

I followed this by reading the 1981 DAW novel, Second Game. This is longer still, and it also features some curious changes. The changes include: changing the planet's name from Velda to Veldq (presumably to make it more "alien", and also perhaps to avoid sounding like a woman's name), changing the narrator's name from Robert O. Lang to Leonard Stromberg (a change I utterly fail to understand unless perhaps that was the original name, and John Campbell insisted on a more Anglo-Saxon lead character), and adding a new social group to Veldq society, the Kismans, low-status merchants. Further changes include more bald exposition of the Ten Thousand Worlds' situation, an altered (and not terribly believable) explanation for the Veldqan level of technology, a hugely expanded subplot about the narrator's Veldqan love interest, including some rather embarrassing sex scenes (and a revised account of the relationship of the sexes on Veldq), and a fair amount of small interpolations, fleshing out details.

On balance I think I prefer the shorter 1962 novel to the 1981 expansion: some of the 1981 additions are sensible fleshing out, but some are silly. The expanded love story is logical and fills in something missing in the 1962 version, but it's not very well done. Other additions, such as the Kismans and the new explanation of Veldqan tech, seem either superfluous or wrong. I wouldn't say, however, that the 1981 version feels padded -- the novelette, in retrospect, seems somewhat rushed, and I would have to say the story basically supports at least 50,000 words.

Finally I went ahead and read the 1991 novelette sequel, by De Vet alone, "Third Game". This is about 15,000 words long. It's set 23 years after the main action of Second Game. There are severe social problems on Veldq, and Leonard Stromberg's half-Veldqan son, Kalin Stromberg, comes to the planet to try to help. After some more harsh evidence of the silly over-violent Veldqan society, and another sometimes embarrassing highly sexed romance, which involved dealing fairly with the oppressed Kisman minority**, and, get this (shades of Asimov's The Stars Like Dust) -- adopt a constitution modelled on the US constitution. It's really a very bad story.

(*There was a curious brief mention of the girl who becomes the narrator's love interest in the novelette -- on reading that, bells went off in my head, and I was surprised that she did not reappear in the story. Which makes me wonder if the novelette wasn't cut before publication, as opposed to the novel being a later expansion.)

(**The Kismans are important in this story as they weren't in the 1981 Second Game, making me wonder if De Vet hadn't already written a version of "Third Game" when he (and MacLean) expanded Cosmic Checkmate to Second Game.)

Birthday Review: Traitor's Gate, by Anne Perry

Anne Perry was born on 28 October 1938 in London, as Juliet Hulme, and the family moved to New Zealand when she was young, for her health. In 1953 she and a close friend murdered the friend's mother (to prevent them moving away), giving her a rather uncommonly appopriate background for a writer of murder mysteries. (This was the subject of Peter Jackson's film Heavenly Creatures.) After serving her time, Hulme changed her name to Anne Perry, and moved to England (and for a time to the United States). She became a Mormon, and as I understand it, two of her novels, the fantasies Tathea and Come, Armageddon, are based on Mormon themes. Her first mystery, The Cater Street Hangman, was published in 1979, and somewhat fortuitously, I discovered her work just a couple of years (and books) later.

She has written novels in several series, most prominent two set in Victorian England: the Thomas and Charlotte Pitt books; and the William Monk/Hester Latterly books. She also wrote several novels about World War I, a whole series of short "Christmas" mysteries, and beginning just last year, books featuring the Pitts' son Daniel. I read the Pitt books and the Monk books with enjoyment for quite a while, but eventually I felt the books were beginning to weaken, and gave up. This review, written over 20 years ago, is of one of the Pitt books that (as you will see) disappointed me. I'm reposting it on the occasion of Perry's 80th birthday.

Review Date: 12 December 1995

TITLE: Traitor`s Gate

AUTHOR: Anne Perry

PUBLISHED: Fawcett Columbine, 1995

ISBN: 0-449-90634-5

This is the latest in Anne Perry`s long series of mystery novels set in late Victorian England (1890, in the present case.) These novels feature Charlotte and Thomas Pitt, he a policeman (just promoted to Superindent), and she an upper-class woman who married shockingly beneath herself, but who maintains a limited entrée to society, useful in helping Thomas with cases involving crimes among the upper class.

Traitor`s Gate features Thomas much more prominently than Charlotte. Thomas` surrogate father, Sir Arthur Desmond, the owner of the estate for which Thomas` actual father was the gamekeeper, has died in his club in London. The death is ruled accidental, or suicide, but his son Matthew, Thomas` close boyhood friend, is convinced it must have been murder, and asks Thomas to investigate.

Thomas is unable to officially investigate Desmond`s death, but rather fortuitously he is asked to investigate a case of missing information at the Colonial Office, to do with Africa and with British support for Cecil Rhodes. As it turns out, Arthur Desmond, formerly employed in the Foreign Office, had just prior to his death been making "wild" accusations of abuse of power in the government support of Rhodes. Naturally, Desmond`s death and the missing information are linked, and, more importantly, both are linked to the mysterious organization Thomas has run afoul of in previous books, The Inner Circle.

As Pitt`s investigations continue, his own life and Matthew`s are threatened, another murder is committed, and finally Pitt`s discoveries trigger a chain reaction of suicides and murders, ending somewhat in medias res with Pitt apparently ready to openly take on the Inner Circle.

The story is entertaining, and the solutions to the crimes are reasonably clever and interesting. However I don`t rank this as highly as the best books in the series for a few reasons. The Inner Circle has become non-credible to me, in its villainy, and its apparent size and power, not to say the incompetence of such a powerful organization in dealing with such a minor figure as Pitt. Pitt`s solutions to the crimes take on the all-too-familiar form of confronting the criminal with the (rather sparse, by OJ standards) evidence of his wrongdoing, upon which he either confesses or commits suicide. The device of having Pitt assigned to investigate a case of espionage is rather unconvincing. Also, the key crime of the book (the second murder) is not only difficult to credit as far as motive is concerned, but is committed in a foolish manner which seems calculated to ultimately draw attention to the murderer (indeed Thomas is misled rather more than I think he should be).

Finally, a key element of the enjoyment of this series is the ongoing stories of the advancing social life of the continuing characters. The books generally feature a love story or two, and this is no exception, but I didn`t find the love stories very involving. And as I said, Charlotte`s role in this book is minor, which is understandable for this book, but something of a drawback nonetheless.

She has written novels in several series, most prominent two set in Victorian England: the Thomas and Charlotte Pitt books; and the William Monk/Hester Latterly books. She also wrote several novels about World War I, a whole series of short "Christmas" mysteries, and beginning just last year, books featuring the Pitts' son Daniel. I read the Pitt books and the Monk books with enjoyment for quite a while, but eventually I felt the books were beginning to weaken, and gave up. This review, written over 20 years ago, is of one of the Pitt books that (as you will see) disappointed me. I'm reposting it on the occasion of Perry's 80th birthday.

Review Date: 12 December 1995

TITLE: Traitor`s Gate

AUTHOR: Anne Perry

PUBLISHED: Fawcett Columbine, 1995

ISBN: 0-449-90634-5

This is the latest in Anne Perry`s long series of mystery novels set in late Victorian England (1890, in the present case.) These novels feature Charlotte and Thomas Pitt, he a policeman (just promoted to Superindent), and she an upper-class woman who married shockingly beneath herself, but who maintains a limited entrée to society, useful in helping Thomas with cases involving crimes among the upper class.

Traitor`s Gate features Thomas much more prominently than Charlotte. Thomas` surrogate father, Sir Arthur Desmond, the owner of the estate for which Thomas` actual father was the gamekeeper, has died in his club in London. The death is ruled accidental, or suicide, but his son Matthew, Thomas` close boyhood friend, is convinced it must have been murder, and asks Thomas to investigate.

Thomas is unable to officially investigate Desmond`s death, but rather fortuitously he is asked to investigate a case of missing information at the Colonial Office, to do with Africa and with British support for Cecil Rhodes. As it turns out, Arthur Desmond, formerly employed in the Foreign Office, had just prior to his death been making "wild" accusations of abuse of power in the government support of Rhodes. Naturally, Desmond`s death and the missing information are linked, and, more importantly, both are linked to the mysterious organization Thomas has run afoul of in previous books, The Inner Circle.

As Pitt`s investigations continue, his own life and Matthew`s are threatened, another murder is committed, and finally Pitt`s discoveries trigger a chain reaction of suicides and murders, ending somewhat in medias res with Pitt apparently ready to openly take on the Inner Circle.

The story is entertaining, and the solutions to the crimes are reasonably clever and interesting. However I don`t rank this as highly as the best books in the series for a few reasons. The Inner Circle has become non-credible to me, in its villainy, and its apparent size and power, not to say the incompetence of such a powerful organization in dealing with such a minor figure as Pitt. Pitt`s solutions to the crimes take on the all-too-familiar form of confronting the criminal with the (rather sparse, by OJ standards) evidence of his wrongdoing, upon which he either confesses or commits suicide. The device of having Pitt assigned to investigate a case of espionage is rather unconvincing. Also, the key crime of the book (the second murder) is not only difficult to credit as far as motive is concerned, but is committed in a foolish manner which seems calculated to ultimately draw attention to the murderer (indeed Thomas is misled rather more than I think he should be).

Finally, a key element of the enjoyment of this series is the ongoing stories of the advancing social life of the continuing characters. The books generally feature a love story or two, and this is no exception, but I didn`t find the love stories very involving. And as I said, Charlotte`s role in this book is minor, which is understandable for this book, but something of a drawback nonetheless.

Thursday, October 25, 2018

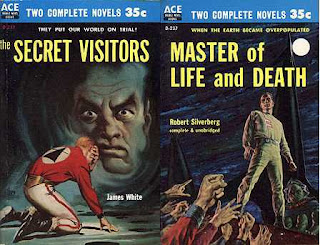

Ace Double Reviews, 21: Master of Life and Death, by Robert Silverberg/The Secret Visitors, by James White

Ace Double Reviews, 21: Master of Life and Death, by Robert Silverberg/The Secret Visitors, by James White (#D-237, 1957, $0.35)

This is an Ace Double pairing two writers who became quite prominent at a very early stage in their careers. Master of Life and Death, about 51,000 words long, was Robert Silverberg's third novel, following the weak juvenile Revolt on Alpha C (1955) (and one of the very first SF novels I ever read), and another 1957 Ace Double, The 13th Immortal. (There are also his two collaborations with Randall Garrett, The Shrouded Planet and The Dawning Light, published as by "Robert Randall", that appeared as a few short stories and a serial in Astounding in 1956 and 1957, but not until 1958/1959 as books.) Silverberg had begun publishing short fiction with "Gorgon Planet", in the February 1954 issue of the Scottish magazine Nebula (after a fair amount of fanwriting, enough to earn him a Retro-Hugo a couple of years ago). He famously beat out Harlan Ellison for a special 1956 Hugo for Best New Author.

The Secret Visitors is about 49,000 words long. It is James White's first novel. White also did a great deal of fanwriting, and he continued this throughout his life. I've read the samples collected in the NESFA book The White Papers, and he was a simply wonderful fan writer. He was also a fine pro writer. His career began with "Assisted Passage", in the January 1953 New Worlds. He was of course most famous for his long series of stories and novels about an interstellar hospital, Sector General, and as such he was noted for his aliens and their curious medical problems.

I've enjoyed a great deal of the work of both writers. Unfortunately, they were not yet fully developed at the time of writing these two novels, and neither story is really very good. The Silverberg novel is explicitly called "complete & unabridged" on the cover, which makes me wonder if there was another longer edition of the White novel. I can't find any evidence of an earlier edition, however. I see a later Ace edition by itself, a UK Digit edition, and a UK New English Library edition, on Abebooks. Some of the Abebooks listings call it a "Doctor Lockhart Adventure", leading me to wonder if there were sequels. Does anyone know?

One more point about Silverberg. I previously have listed particularly prolific Ace Double authors, but I have forgotten Silverberg. I could advance the excuse that he wrote many of his Doubles under pseudonyms (Calvin Knox most often, but also Ivar Jorgenson and David Osborne), but that's not the real reason. The real reason I didn't list him is that I forgot to think of him as an Ace Double author. But he was -- in his early, "hack", career. He wrote, as far as I can tell, 13 Ace Double halves, in 12 different books.

Master of Life and Death is an exemplar, it seems to me, of several features of SF of the 50s and 60s. For one thing, it is a strikingly didactic novel -- in this case on the subject of overpopulation. For another thing, it features what I believe is really the standard political future of SF of that period. This future, perhaps surprisingly, was not capitalist in nature, it was not (at least not overtly) America-dominated. Instead, the "default" state of world governance as of X years in the future (X could be 50 or 200 or 300), in 1960 or so, as described by SF, consisted of the United Nations in control, with a basically socialist (though rarely very detailed) economy. All this seems to me, in rereading many older stories, to be accepted all but without thought. That was simply the way things were going to be. There was nothing pro-Soviet about this -- indeed, if there was a backstory (there isn't in the book at hand) it might detail how wicked the Soviets were, until they were subsumed peacefully under the world government.

But economy, to be sure, isn't what Master of Life and Death is about. Though it must be said that the implied economic underpinning to this novel is naive and simplistic -- much like the political underpinning, and the scientific underpinning. It is, indeed, not a very good novel, hardly thought out at all. Though also told with a certain efficiency -- not exactly energy or verve, but efficiency, professionalism -- that makes it a fast read, and a book that holds the attention for the brief time it takes to read, if no longer.

The book is told in third-person but from the POV of Ray Walton, as the book opens the Assistant Administrator of the six-week-old Department of Population Equalization, or Popeek. The job of Popeek, in the horribly overpopulated world of 2232, is to balance population stresses. Reality Check #1 -- what is Silverberg's estimate of the horrible, insupportable, population level which we will have finally reached 275 years in the book's future? 7 billion. What is the current world population [as of my writing this review, 15 or so years ago], only 46 years in the book's future, according to the US Census Bureau? 6.3 billion. This doesn't invalidate the book, but it does speak to a certain failure of imagination. (I'm a bit cruel to him -- this failure of imagination was essentially universal at this time in the '50s.)

What does Popeek do, then? It moves people from overpopulated areas to sparsely populated areas. (Indeed, one of the first things we see Walton do is sign an order to move several thousand people from Belgium to Patagonia. The book doesn't consider the logistics of this.) Also, it arranges for unsuitable people to be euthanized -- babies with defects such as a potential to become tubercular, and old people who have become a burden on society. A familiar idea, but not really handled very well here. Anyway, Walton is confronted by a great poet, a favorite of Walton himself, who begs for the life of his young son. Walton secretly adjusts the records to save the boy's life, but his action is detected by his malcontent brother, whom Walton has given a job at Popeek. Now Walton is under his brother's thumb. Then an assassin kills Walton's boss, and Walton suddenly is in charge of all of Popeek.

He finds himself struggling with his own guilt, with his brother's threats, with internal problems in the department, and with three secret projects authorized by the former director: an immortality serum, terraformation of Venus, and FTL travel to allow colonization of nearby planets. The first is of course a disaster in an already overpopulated world. The second is apparently close to success -- but nothing has been heard from the planet Venus in, oh, a few days. The third is also close to success -- indeed, a ship has already been sent exploring! (Here though is another example of not thinking things through -- Silverberg details a plan to send ships to a potential habitable planet each carrying 1000 people, until a billion people have been moved. OK, suppose somehow ships can be built and launched at the rate of 1 per day -- how long would it take to move 1,000,000,000 people? Over 2700 years! Similar problems, really, would affect the use of Venus or any other "local" planet as a bleeder valve for excess population.)

Walton finds himself driven, in a ridiculously short time (the action of the book takes some 9 days) to absurdly evil actions to maintain his power, quash opposition, and push through the actions he feels necessary. It is ambiguous at times whether he is really after power or sincerely trying to do good. I felt for a while that Silverberg was trying for a tragic look at a good man corrupted. I felt for another while that he was trying for a satiric over the top look at an exaggerated regime of population control. But neither really comes off. And the book stumbles to a disappointing close, with "aliens ex machina" to solve some of the problems (though to be fair with a slightly unexpected ending twist).

Not a good book. The action is implausible, the general setup implausible, the science is dodgy, and the ending rushed and unsatisfactory.

The Secret Visitors also has serious problems, though in sum I enjoyed the story a bit more. It opens with Doctor John Lockhart, a WWII veteran, on a curious British Intelligence mission to prevent an upcoming war. His job is to identify when a mysterious old man is about to die, and to get to him in time for a last minute interrogation. When he does so, the man gibbers in an unknown language, and the Intelligence types seem rather eager to conclude that he is an alien. Before long there seem to be several factions of aliens to deal with, including a beautiful girl, several of these dying old men, and a crew at a hotel in Northern Ireland (not coincidentally, I'm sure, White's home).

The Intelligence people soon make there way to this hotel, and they learn that an evil alien travel agency is fomenting war on Earth in order that the planet, the most beautiful by far in the Galaxy (apparently because it is the only planet with axial tilt!), be maintained conveniently unspoiled for alien tourism. (It should be noted that the aliens generally seem to be fully human -- basically Spanish.) The beautiful girl is trying to smuggle evidence of this perfidy to the Galactic Court in order that the agency can be stopped. For this she needs the help of some humans -- and she seems particularly interested in the help of Lockhart. But is she telling the truth?

This setup is so extravagantly silly as to almost make the book impossible to continue with. And it isn't helped when White can't seem to decide if his method of interstellar travel involves time dilation or not (there's a man from two centuries in the past as a result of one space trip, but on the other hand this impending war seems possible to stop in short order via a round trip to the capitol planet and back.) And there is the absurd bit that Earth's medical science is so advanced compared to the aliens that Lockhart is treated almost like a god. (But the aliens have an immortality treatment -- that, it turns out, for unconvincing reasons, is WHY their medical science stinks.) And there's the part about Earth music being so superior that the aliens are reduced to tears of joy and admiration by an amateur harp player.

Still, there are good parts, such as the alien Grosni, who live partly in hyperspace. Lockhart, in a segment recalling White's Sector General series, must treat a sick Grosni. The story spirals outward from the beginning premise, leading to an action-packed but again not very convincing conclusion, with it must be said a fairly clever final resolution to the final battle. It's by no means a good novel, and I don't think it could possibly sell today, but it is in many places pleasant and imaginative entertainment.

|

| (Covers by ? and Ed Emshwiller) |

The Secret Visitors is about 49,000 words long. It is James White's first novel. White also did a great deal of fanwriting, and he continued this throughout his life. I've read the samples collected in the NESFA book The White Papers, and he was a simply wonderful fan writer. He was also a fine pro writer. His career began with "Assisted Passage", in the January 1953 New Worlds. He was of course most famous for his long series of stories and novels about an interstellar hospital, Sector General, and as such he was noted for his aliens and their curious medical problems.

I've enjoyed a great deal of the work of both writers. Unfortunately, they were not yet fully developed at the time of writing these two novels, and neither story is really very good. The Silverberg novel is explicitly called "complete & unabridged" on the cover, which makes me wonder if there was another longer edition of the White novel. I can't find any evidence of an earlier edition, however. I see a later Ace edition by itself, a UK Digit edition, and a UK New English Library edition, on Abebooks. Some of the Abebooks listings call it a "Doctor Lockhart Adventure", leading me to wonder if there were sequels. Does anyone know?

One more point about Silverberg. I previously have listed particularly prolific Ace Double authors, but I have forgotten Silverberg. I could advance the excuse that he wrote many of his Doubles under pseudonyms (Calvin Knox most often, but also Ivar Jorgenson and David Osborne), but that's not the real reason. The real reason I didn't list him is that I forgot to think of him as an Ace Double author. But he was -- in his early, "hack", career. He wrote, as far as I can tell, 13 Ace Double halves, in 12 different books.

Master of Life and Death is an exemplar, it seems to me, of several features of SF of the 50s and 60s. For one thing, it is a strikingly didactic novel -- in this case on the subject of overpopulation. For another thing, it features what I believe is really the standard political future of SF of that period. This future, perhaps surprisingly, was not capitalist in nature, it was not (at least not overtly) America-dominated. Instead, the "default" state of world governance as of X years in the future (X could be 50 or 200 or 300), in 1960 or so, as described by SF, consisted of the United Nations in control, with a basically socialist (though rarely very detailed) economy. All this seems to me, in rereading many older stories, to be accepted all but without thought. That was simply the way things were going to be. There was nothing pro-Soviet about this -- indeed, if there was a backstory (there isn't in the book at hand) it might detail how wicked the Soviets were, until they were subsumed peacefully under the world government.

But economy, to be sure, isn't what Master of Life and Death is about. Though it must be said that the implied economic underpinning to this novel is naive and simplistic -- much like the political underpinning, and the scientific underpinning. It is, indeed, not a very good novel, hardly thought out at all. Though also told with a certain efficiency -- not exactly energy or verve, but efficiency, professionalism -- that makes it a fast read, and a book that holds the attention for the brief time it takes to read, if no longer.

The book is told in third-person but from the POV of Ray Walton, as the book opens the Assistant Administrator of the six-week-old Department of Population Equalization, or Popeek. The job of Popeek, in the horribly overpopulated world of 2232, is to balance population stresses. Reality Check #1 -- what is Silverberg's estimate of the horrible, insupportable, population level which we will have finally reached 275 years in the book's future? 7 billion. What is the current world population [as of my writing this review, 15 or so years ago], only 46 years in the book's future, according to the US Census Bureau? 6.3 billion. This doesn't invalidate the book, but it does speak to a certain failure of imagination. (I'm a bit cruel to him -- this failure of imagination was essentially universal at this time in the '50s.)

What does Popeek do, then? It moves people from overpopulated areas to sparsely populated areas. (Indeed, one of the first things we see Walton do is sign an order to move several thousand people from Belgium to Patagonia. The book doesn't consider the logistics of this.) Also, it arranges for unsuitable people to be euthanized -- babies with defects such as a potential to become tubercular, and old people who have become a burden on society. A familiar idea, but not really handled very well here. Anyway, Walton is confronted by a great poet, a favorite of Walton himself, who begs for the life of his young son. Walton secretly adjusts the records to save the boy's life, but his action is detected by his malcontent brother, whom Walton has given a job at Popeek. Now Walton is under his brother's thumb. Then an assassin kills Walton's boss, and Walton suddenly is in charge of all of Popeek.

He finds himself struggling with his own guilt, with his brother's threats, with internal problems in the department, and with three secret projects authorized by the former director: an immortality serum, terraformation of Venus, and FTL travel to allow colonization of nearby planets. The first is of course a disaster in an already overpopulated world. The second is apparently close to success -- but nothing has been heard from the planet Venus in, oh, a few days. The third is also close to success -- indeed, a ship has already been sent exploring! (Here though is another example of not thinking things through -- Silverberg details a plan to send ships to a potential habitable planet each carrying 1000 people, until a billion people have been moved. OK, suppose somehow ships can be built and launched at the rate of 1 per day -- how long would it take to move 1,000,000,000 people? Over 2700 years! Similar problems, really, would affect the use of Venus or any other "local" planet as a bleeder valve for excess population.)

Walton finds himself driven, in a ridiculously short time (the action of the book takes some 9 days) to absurdly evil actions to maintain his power, quash opposition, and push through the actions he feels necessary. It is ambiguous at times whether he is really after power or sincerely trying to do good. I felt for a while that Silverberg was trying for a tragic look at a good man corrupted. I felt for another while that he was trying for a satiric over the top look at an exaggerated regime of population control. But neither really comes off. And the book stumbles to a disappointing close, with "aliens ex machina" to solve some of the problems (though to be fair with a slightly unexpected ending twist).

Not a good book. The action is implausible, the general setup implausible, the science is dodgy, and the ending rushed and unsatisfactory.

The Secret Visitors also has serious problems, though in sum I enjoyed the story a bit more. It opens with Doctor John Lockhart, a WWII veteran, on a curious British Intelligence mission to prevent an upcoming war. His job is to identify when a mysterious old man is about to die, and to get to him in time for a last minute interrogation. When he does so, the man gibbers in an unknown language, and the Intelligence types seem rather eager to conclude that he is an alien. Before long there seem to be several factions of aliens to deal with, including a beautiful girl, several of these dying old men, and a crew at a hotel in Northern Ireland (not coincidentally, I'm sure, White's home).

The Intelligence people soon make there way to this hotel, and they learn that an evil alien travel agency is fomenting war on Earth in order that the planet, the most beautiful by far in the Galaxy (apparently because it is the only planet with axial tilt!), be maintained conveniently unspoiled for alien tourism. (It should be noted that the aliens generally seem to be fully human -- basically Spanish.) The beautiful girl is trying to smuggle evidence of this perfidy to the Galactic Court in order that the agency can be stopped. For this she needs the help of some humans -- and she seems particularly interested in the help of Lockhart. But is she telling the truth?

This setup is so extravagantly silly as to almost make the book impossible to continue with. And it isn't helped when White can't seem to decide if his method of interstellar travel involves time dilation or not (there's a man from two centuries in the past as a result of one space trip, but on the other hand this impending war seems possible to stop in short order via a round trip to the capitol planet and back.) And there is the absurd bit that Earth's medical science is so advanced compared to the aliens that Lockhart is treated almost like a god. (But the aliens have an immortality treatment -- that, it turns out, for unconvincing reasons, is WHY their medical science stinks.) And there's the part about Earth music being so superior that the aliens are reduced to tears of joy and admiration by an amateur harp player.

Still, there are good parts, such as the alien Grosni, who live partly in hyperspace. Lockhart, in a segment recalling White's Sector General series, must treat a sick Grosni. The story spirals outward from the beginning premise, leading to an action-packed but again not very convincing conclusion, with it must be said a fairly clever final resolution to the final battle. It's by no means a good novel, and I don't think it could possibly sell today, but it is in many places pleasant and imaginative entertainment.

Wednesday, October 24, 2018

Birthday Review: Stories of Sofia Samatar

Birthday Review: Stories of Sofia Samatar

Today is Sofia Samatar's birthday, and again I've assembled a collection of my reviews of her stories. This isn't as long as some of my other similar posts, simply because Samatar hasn't been publishing as long. But she's a major major writer, one of my very favorites already. I haven't written about her novels, A Stranger in Olondria and The Winged Histories, but I should add that I recommend them both very highly. The second novel didn't seem to get quite as much attention as the first, but it's quite remarkable too, and in particular it closes very strongly.

(Locus, October 2012)

Clarkesworld's August issue features a couple of stories by writers I like a lot, and one by a writer new to me. So naturally the story by the unfamiliar writer, Sofia Samatar, worked best! "Honey Bear" tells of a family trip to the sea, a couple and their one child, but we slowly realize that the child isn't quite a regular human child, and that indeed the human world isn't normal at all any more. The mother narrates, desperately hoping her child, whom she loves, will remember this day, while the father is worried for hard to understand reasons. The problem is the Fair Folk, who seem to rule the Earth now (it's not clear if they are a version of fairies, or if they are aliens called that because of some resemblance). I won't say what's going on (though most readers will guess) -- because the slow reveal, and the mother's desperate, hopeless, love for her child, work together beautifully.

(Locus, April 2014)

The other original SF story in the March Lightspeed is "How to Get back to the Forest", by Sofia Samatar, who has quite rapidly become a major voice in SF/F, with one marvelous novels and several short stories (including the new Nebula nominee "Selkie Stories are for Losers") that are not only outstanding but display a striking range of themes and concerns. This latest is a scary story of a near future in which children are taken away from their parents to be raised (indoctrinated) in camps. The narrator's friend Cee rebels, insisting that she can expel the tracking bug inside her, and pulling the narrator into some of her schemes. In the end it's heartbreaking, and convincing, and intriguing in its continuing reveal of the strange dark future it portrays.

(Locus, January 2017)

Perhaps the most overt "reimagination" in The Starlit Wood is Sofia Samatar’s "The Tale of Mahliya and Mauhub and the White-Footed Gazelle", which is a look at an Arabic tale of at least a millennium ago, translated into English for the first time only last year. Samatar’s story literally "deconstructs" is, takes it apart, looks at each of the characters -- and then cunningly reassembles it, in front of the reader, in the context of the present. It is on the one hand clever -- but still it remains a story, and a moving story.

(Locus, March 2018)

I continue to catch up on some 2017 stuff I missed. For example, Sofia Samatar’s collection Tender: Stories. Truly this is one of the best collections I’ve seen in some time. This exceptional debut collection includes two new stories, "An Account of the Land of Witches", and "Fallow". Both are remarkable. "Fallow" has perhaps got more notice. It’s clearly one of the best novellas of the year. It’s set on a planet colonized by what seem to be perhaps an Amish sect, fleeing an increasingly ruined Earth. They scratch out a difficult living in what seems maybe a domed colony -- with something called the Castle nearby (is that the spaceship they came on? Part of the appeal of the story is that we are told relatively little.) The story is told by a woman who has written stories before, only to see them rejected (literally, as a waste of paper) -- now she will tell the truth about her life so far -- or, really, about three people who to some degree rebelled against that society: her teacher, Miss Snowfall; a man named Brother Lookout, a "Young Evangelist" who had become involved with a visiting "Earthman"; and finally her sister Temar, who had gone to work at the Castle. Samatar invests all this with mystery, with hints of the state of the ruined Earth (and their hopes to return), with slant looks at the details of the religion followed in this colony, with precise and affecting characterization -- it’s a sad but beautiful and not quite hopeless story.

"An Account of the Land of Witches" is quite as good in a very different way. It opens with a lyrical narrative by Arta, a slave who is taken by her master (a merchant) to the Land of Witches, where she learns their magic -- or Dream Science -- which involves language and the manipulation of time. This is absolutely lovely writing, and the magical system is beautiful. There follows -- ever in different well realized voices -- a "refutation" of Arta’s account by her angry master; and then a desperate section told by a Sudanese woman trapped back home by visa problems (and local strife) as she tries to research the fragments that make up Arta’s account and her master’s refutation for her degree from a US university; then a lexicon of the witches’ magical language, and then a strange almost mystical account of a journey in search of the Land. This is really striking, original, and, like "Fallow", mysterious.

Today is Sofia Samatar's birthday, and again I've assembled a collection of my reviews of her stories. This isn't as long as some of my other similar posts, simply because Samatar hasn't been publishing as long. But she's a major major writer, one of my very favorites already. I haven't written about her novels, A Stranger in Olondria and The Winged Histories, but I should add that I recommend them both very highly. The second novel didn't seem to get quite as much attention as the first, but it's quite remarkable too, and in particular it closes very strongly.

(Locus, October 2012)

Clarkesworld's August issue features a couple of stories by writers I like a lot, and one by a writer new to me. So naturally the story by the unfamiliar writer, Sofia Samatar, worked best! "Honey Bear" tells of a family trip to the sea, a couple and their one child, but we slowly realize that the child isn't quite a regular human child, and that indeed the human world isn't normal at all any more. The mother narrates, desperately hoping her child, whom she loves, will remember this day, while the father is worried for hard to understand reasons. The problem is the Fair Folk, who seem to rule the Earth now (it's not clear if they are a version of fairies, or if they are aliens called that because of some resemblance). I won't say what's going on (though most readers will guess) -- because the slow reveal, and the mother's desperate, hopeless, love for her child, work together beautifully.

(Locus, April 2014)

The other original SF story in the March Lightspeed is "How to Get back to the Forest", by Sofia Samatar, who has quite rapidly become a major voice in SF/F, with one marvelous novels and several short stories (including the new Nebula nominee "Selkie Stories are for Losers") that are not only outstanding but display a striking range of themes and concerns. This latest is a scary story of a near future in which children are taken away from their parents to be raised (indoctrinated) in camps. The narrator's friend Cee rebels, insisting that she can expel the tracking bug inside her, and pulling the narrator into some of her schemes. In the end it's heartbreaking, and convincing, and intriguing in its continuing reveal of the strange dark future it portrays.

(Locus, January 2017)

Perhaps the most overt "reimagination" in The Starlit Wood is Sofia Samatar’s "The Tale of Mahliya and Mauhub and the White-Footed Gazelle", which is a look at an Arabic tale of at least a millennium ago, translated into English for the first time only last year. Samatar’s story literally "deconstructs" is, takes it apart, looks at each of the characters -- and then cunningly reassembles it, in front of the reader, in the context of the present. It is on the one hand clever -- but still it remains a story, and a moving story.

(Locus, March 2018)

I continue to catch up on some 2017 stuff I missed. For example, Sofia Samatar’s collection Tender: Stories. Truly this is one of the best collections I’ve seen in some time. This exceptional debut collection includes two new stories, "An Account of the Land of Witches", and "Fallow". Both are remarkable. "Fallow" has perhaps got more notice. It’s clearly one of the best novellas of the year. It’s set on a planet colonized by what seem to be perhaps an Amish sect, fleeing an increasingly ruined Earth. They scratch out a difficult living in what seems maybe a domed colony -- with something called the Castle nearby (is that the spaceship they came on? Part of the appeal of the story is that we are told relatively little.) The story is told by a woman who has written stories before, only to see them rejected (literally, as a waste of paper) -- now she will tell the truth about her life so far -- or, really, about three people who to some degree rebelled against that society: her teacher, Miss Snowfall; a man named Brother Lookout, a "Young Evangelist" who had become involved with a visiting "Earthman"; and finally her sister Temar, who had gone to work at the Castle. Samatar invests all this with mystery, with hints of the state of the ruined Earth (and their hopes to return), with slant looks at the details of the religion followed in this colony, with precise and affecting characterization -- it’s a sad but beautiful and not quite hopeless story.

"An Account of the Land of Witches" is quite as good in a very different way. It opens with a lyrical narrative by Arta, a slave who is taken by her master (a merchant) to the Land of Witches, where she learns their magic -- or Dream Science -- which involves language and the manipulation of time. This is absolutely lovely writing, and the magical system is beautiful. There follows -- ever in different well realized voices -- a "refutation" of Arta’s account by her angry master; and then a desperate section told by a Sudanese woman trapped back home by visa problems (and local strife) as she tries to research the fragments that make up Arta’s account and her master’s refutation for her degree from a US university; then a lexicon of the witches’ magical language, and then a strange almost mystical account of a journey in search of the Land. This is really striking, original, and, like "Fallow", mysterious.

Birthday Review: Stories of Jack Skillingstead

Birthday Review: Stories of Jack Skillingstead

Today is the birthday of my old co-worker Jack Skillingstead. Well, we weren't exactly co-workers, but we both worked at Boeing -- only Jack was in Seattle, and I'm in St. Louis. I didn't know that when I started reading his work, back in around 2004, but I did know he was an exciting new writer. Here's a selection of my Locus reviews of his stories (not including a story I included in one of my early Best of the Year volumes, "Everyone Bleeds Through" -- I can't find a review of that in my files.)

(Locus, August 2018)

Jack Skillingstead’s "Straconia" is an effective sort of Kafkaesque look at a man drifting though life, not much engaged with his marriage, who mysteriously ends up in the title city, struggling to deal with its very strange rules. He tries to find a way back but, well, I mentioned Kafka. (I should also note that somehow the story also reminded me as well of Gene Wolfe’s great early novella "Forlesen".)

(Locus, September 2004)

Jack Skillingstead's first few stories have been consistently impressive, "Transplant" being the latest. The narrator is a genetic freak who may be immortal he can regenerate any injured part. A rich man sponsoring a generation starship uses parts harvested from the narrator to maintain his life, hoping to survive the journey. The story concerns the narrator's attempt to make an independent life among the short-lived passengers difficult both because of the other man's insistence on having him near at hand, and because of the traditional difficulty immortals have dealing with the constant losses of mortal friends.

(Locus, May 2005)

"Bean There", by Jack Skillingstead, is a sweet story of a skeptical coffee shop owner in a world apparently gone mad. Strange news stories abound levitated bicycles, teleporting people, Jerry Garcia returned from the dead. Burt refuses to believe, but his girlfriend Aimee, a sculptor, talks of "Harbingers of Evolution". We can all see where the story is headed, and it gets there nicely.

(Locus, January 2006)

Jack Skillingstead’s "Are You There?" is about a parapoliceman tracking a serial killer. His best lead is the "Loved One" he finds a "copy" of the killer’s mother’s brain, preserved on a computer. It works well enough as a crime story, and it works even better as a story about the detective and his relationships with women: his ex-wife, a woman he has met in a chat room but not in person, and the electronic copy of his quarry’s mother.

(Locus, April 2006)

And Jack Skillingstead’s "Life on the Preservation" tells of a girl from a future Earth destroyed by aliens who penetrates into Seattle, which has been maintained in a time loop as a sort of reminder of what Earth was like. Her job is to destroy the alien time loop machinery but this is complicated when she meets a boy … I think this may be the best story yet by this fine new writer.

(Locus, August 2006)

Jack Skillingstead’s "Girl in the Empty Apartment", about a Joe Skadan, a failing writer in a near future troubled by "Harbingers", mysterious entities that seem to manifest in dreams, and that may be linked to multiple disappearances. Joe’s girlfriend dumps him, apparently for a Homeland Security agent, and then Joe becomes a subject of investigation. At the same time he encounters a mysterious young woman, who may offer his only, ambiguous, hope for escape.

(Locus, November 2007)

In Jack Skillingstead’s thoughtful and effective "Strangers on a Bus" a woman taking a bus back home to escape her abusive boyfriend encounters an odd man with a rather solipsistic life view he thinks the stories he tells become reality for everyone.

(Locus, July 2009)

The Spring On Spec has finally arrived, with nice pieces from Jack Skillingstead and Tony Pi. Skillingstead’s "Einstein’s Theory" is a quiet story, in which an alternate Einstein regrets an act of adultery with a co-worker at the patent office and reflects on his wasted life (namechecking Hugo Gernsback along the way).

(Locus, August 2013)

Jack Skillingstead, in "Arlington", describes a solo flight in a small plane that ends up in an alternate world, but a terribly dangerous alternate world, with menacing creatures apparently kidnapping people. The general outline is familiar, but the resolution is effective.

(Locus, March 2017)

I also was intrigued by Jack Skillingstead’s "Destination", a dark story about the widening gulf between the privileged even quite minorly privileged and the have-nots. Brad is a game designer, which gives him access to a decent place inside a corporate enclave, and one day he is summoned to a mandatory training exercise, a real world game called "Destination", which involves a fairly random (perhaps?) trip to the "outside" world. Brad’s trip is (a bit too predictably) eye-opening, and he is given an ultimatum of sorts.

(Locus, August 2018)

Jack Skillingstead’s "Straconia" is an effective sort of Kafkaesque look at a man drifting though life, not much engaged with his marriage, who mysteriously ends up in the title city, struggling to deal with its very strange rules. He tries to find a way back but, well, I mentioned Kafka. (I should also note that somehow the story also reminded me as well of Gene Wolfe’s great early novella "Forlesen".)

Today is the birthday of my old co-worker Jack Skillingstead. Well, we weren't exactly co-workers, but we both worked at Boeing -- only Jack was in Seattle, and I'm in St. Louis. I didn't know that when I started reading his work, back in around 2004, but I did know he was an exciting new writer. Here's a selection of my Locus reviews of his stories (not including a story I included in one of my early Best of the Year volumes, "Everyone Bleeds Through" -- I can't find a review of that in my files.)

(Locus, August 2018)

Jack Skillingstead’s "Straconia" is an effective sort of Kafkaesque look at a man drifting though life, not much engaged with his marriage, who mysteriously ends up in the title city, struggling to deal with its very strange rules. He tries to find a way back but, well, I mentioned Kafka. (I should also note that somehow the story also reminded me as well of Gene Wolfe’s great early novella "Forlesen".)

(Locus, September 2004)

Jack Skillingstead's first few stories have been consistently impressive, "Transplant" being the latest. The narrator is a genetic freak who may be immortal he can regenerate any injured part. A rich man sponsoring a generation starship uses parts harvested from the narrator to maintain his life, hoping to survive the journey. The story concerns the narrator's attempt to make an independent life among the short-lived passengers difficult both because of the other man's insistence on having him near at hand, and because of the traditional difficulty immortals have dealing with the constant losses of mortal friends.

(Locus, May 2005)

"Bean There", by Jack Skillingstead, is a sweet story of a skeptical coffee shop owner in a world apparently gone mad. Strange news stories abound levitated bicycles, teleporting people, Jerry Garcia returned from the dead. Burt refuses to believe, but his girlfriend Aimee, a sculptor, talks of "Harbingers of Evolution". We can all see where the story is headed, and it gets there nicely.

(Locus, January 2006)

Jack Skillingstead’s "Are You There?" is about a parapoliceman tracking a serial killer. His best lead is the "Loved One" he finds a "copy" of the killer’s mother’s brain, preserved on a computer. It works well enough as a crime story, and it works even better as a story about the detective and his relationships with women: his ex-wife, a woman he has met in a chat room but not in person, and the electronic copy of his quarry’s mother.

(Locus, April 2006)

And Jack Skillingstead’s "Life on the Preservation" tells of a girl from a future Earth destroyed by aliens who penetrates into Seattle, which has been maintained in a time loop as a sort of reminder of what Earth was like. Her job is to destroy the alien time loop machinery but this is complicated when she meets a boy … I think this may be the best story yet by this fine new writer.

(Locus, August 2006)

Jack Skillingstead’s "Girl in the Empty Apartment", about a Joe Skadan, a failing writer in a near future troubled by "Harbingers", mysterious entities that seem to manifest in dreams, and that may be linked to multiple disappearances. Joe’s girlfriend dumps him, apparently for a Homeland Security agent, and then Joe becomes a subject of investigation. At the same time he encounters a mysterious young woman, who may offer his only, ambiguous, hope for escape.

(Locus, November 2007)

In Jack Skillingstead’s thoughtful and effective "Strangers on a Bus" a woman taking a bus back home to escape her abusive boyfriend encounters an odd man with a rather solipsistic life view he thinks the stories he tells become reality for everyone.

(Locus, July 2009)

The Spring On Spec has finally arrived, with nice pieces from Jack Skillingstead and Tony Pi. Skillingstead’s "Einstein’s Theory" is a quiet story, in which an alternate Einstein regrets an act of adultery with a co-worker at the patent office and reflects on his wasted life (namechecking Hugo Gernsback along the way).

(Locus, August 2013)