Ace Double Reviews, 62: Ring Around the Sun, by Clifford D. Simak/Cosmic Manhunt, by L. Sprague de Camp (#D-61, 1954, $0.35)

a review by Rich Horton

This early Ace Double stands as one of the better pairings in the series' history. Both authors are SFWA Grand Masters. Both books are fine work, and very characteristic of the author. Neither story is quite a classic, and as such the book stands just shy of the very best Doubles (a couple of suggestions for the best: Conan the Conqueror/The Sword of Rhiannon; and, if one allows a "recombination", the late repackaging of The Dragon Masters and The Last Castle).

Ring Around the Sun is a Complete and Unabridged reprint of a 1953 Simon and Schuster hardcover, which was serialized beginning in December 1952 in Galaxy. It is about 75,000 words (one of the longest Ace Double halves). Cosmic Manhunt is called an "Ace Original", but it is a very lightly revised reprinting if De Camp's 1949 Astounding serial "The Queen of Zamba". It is about 50,000 words long.

Clifford Simak's first SF stories were more or less standard (but well regarded) pre-Campbell pulp adventures -- Isaac Asimov liked his first, "World of the Red Sun", enough to retell it aloud to his elementary school friends. (Asimov later wrote a harshly critical letter to Astounding about one of Simak's first stories for John Campbell, and Simak replied asking for advice on how to improve. Asimov abashedly reread the story and decided he was wrong and Simak was right.) He stopped writing for several years in the 30s, only to be lured back by John Campbell. Simak, with Williamson, Leinster, and a few others, was able to make the transition from 30s pulp to the more serious science fiction Campbell wanted. Simak made his biggest impression over the next decade with the series of stories that became his fixup novel City, which won the International Fantasy Award in 1953. He published two of the earlier Galaxy serials: "Time Quarry" (book title: Time and Again), which appeared in the first three issues of Galaxy (October through November 1950) and Ring Around the Sun. (He also had a novel published as a "Galaxy Novel" in 1951: Empire, a very little known book, by all accounts little known for good reason.)

Ring Around the Sun is an intriguing effort that I don't think quite comes off. The hero is Jay Vickers, a writer living in upstate New York. He lives alone, with apparently just one friend, a tastefully named old man named Horton Flanders. His agent is a lovely woman named Ann Carter, but her evident interest in him is hopeless: Jay can't forget his love for Kathleen Preston, a rich neighbor girl in his home town (presumably located in Southwestern Wisconsin, where Simak routinely set stories) who was sent away by her parents to keep her from poverty-stricken Jay's attention. Jay feels different in other ways: there is the memory of an enchanted valley he visited with Kathleen, and of a strange place he went to as a boy, by the agency of an old top.

Jay is called to New York to meet with a man who wants him to write an exposé of some new products that have been showing up. These are things like a razor blade that never wears out, a light bulb that never burns out, and, most radically, a car that will run forever: the Forever car. George Crawford represents an industry group that is afraid of the effect of these products on the world's economy, and he wants Jay to write articles about the danger. But Jay distrusts Crawford and refuses. Then his friend Horton Flanders disappears, and suddenly people seem suspicious of Jay himself. And of anyone involved with the Forever car and the other new products. It seems that there are "supermen" among us, and that Jay may be one of those who doesn't recognize his talents. Jay escapes a potential lynching and heads for his hometown to try to unravel the mysteries of his birth and upbringing, and of the enchanted valley he once visited.

The story gets a little stranger from there. It seems that there are not just supermen but androids involved. And parallel worlds -- possibly available for colonization. And messages from the stars. And multiple copies of the same individual. Horton Flanders is in on the whole thing. George Crawford's industry group is engaged in fomenting a war if that's what it takes to stop the incursion of these miracle products and to stop the subjugation of "normal" people by supermen. Ann Carter may be a superwoman herself. And, indeed, the destinies of Flanders, Vickers, Carter, and Crawford seem all to be most curiously intertwined.

This is a very imaginative and pretty thoughtful and ambitious story. Still, I don't think Simak quite brings off what he's trying. Vickers is a thinnish character, and his relationship with Ann Carter is thinner still. Simak's ideas, and his moral, are interesting, but not quite developed as well as I'd have liked. The conclusion is just a bit rapid. (Interestingly, he reused some of these ideas (not all!) in a later novelette, "Carbon Copy" (Galaxy, December 1957).)

Finally, I note that the novel is blurbed "Easily the best Science Fiction novel so far in 1953" -- New York Herald Tribune. I don't know when it appeared in 1953 (in book form), but that's a striking comment given that books published that year included The Demolished Man, Fahrenheit 451, Childhood's End, More Than Human, The Paradox Men, The Sword of Rhiannon, Second Foundation, and The Space Merchants. (This doesn't include serials from 1953 such as "The Caves of Steel" and "Mission of Gravity" that became books a year later.) 1953 was truly an annus mirabilis for the SF field, and Ring Around the Sun is a worthy supporting player among the long list of great work from that year.

Cosmic Manhunt, as I mentioned, is a slight revision of L. Sprague de Camp's 1949 serial "The Queen of Zamba". According to de Camp's foreword to a later reprint, the only change was in the name of the hero's sidekick. The Chinese name Chuen from the serial became Yano (Japanese, or more specifically Okinawan) in the Ace edition, due to Don Wollheim's concern that Chinese people were unpopular as a result of the Korean War. Otherwise the stories are identical as far as I can tell. The book was reprinted by itself by Ace in 1966, the title changed again, to A Planet Called Krishna. And it was reprinted in 1977, restored to the original text and title, in an Asimov's Choice paperback (from Davis Publications), with the Krishna novelette "Perpetual Motion" appended.

I believe this is the first of de Camp's Krishna novels. Quite a few followed, all with a Z place name in the title: The Hand of Zei (1951), The Virgin of Zesh (1953), The Tower of Zanid (1958), The Hostage of Zir (1977), The Bones of Zora (1983) and The Swords of Zinjaban (1991). These last two were co-written with his wife, Catherine Crook de Camp. (There is also a book called The Search for Zei which I assume is a retitling of The Hand of Zei. (It turns out that some editions split The Hand of Zei into two parts, with The Search for Zei being the other part.) The Krishna novels are the main part of his Viagens Interplanetarias series, which includes a number of other stories and the novel Rogue Queen (1951). The most recognizable gimmicks of the series are that the future Earth is dominated by Brazil, hence the lingua franca is Portuguese, and that space travel is restricted to light speed. De Camp claimed this was to keep the books SF: to violate relativity would make them fantasy. Maybe so, but the silly biology of the Krishna books seems equally fantastical.

In The Queen of Zamba (a title much to be preferred to Cosmic Manhunt in my view), private investigator Victor Hasselborg is hired by a rich man to track down his daughter, who has run off with an ineligible rogue. Hasselborg agrees to the job, then finds himself obligated to travel to Krishna, where the couple has apparently decamped (pun intended). Worse, he falls in love with the bad guy's abandoned wife, but she'll have to wait 9 years or so for him to return. (Krishna appears to be at Alpha Centauri or perhaps Barnard's Star, based on travel time.)

On Krishna, Hasselborg disguises himself as a Krishnan portrait painter. He follows the trail of the two lovers to one kingdom, where he meets the King (or Dour) and is rapidly slapped in jail. Before long he is fighting a duel for his life with the Dour. He escapes to another town, and falls in with the local high priest, also arranging to paint the Emperor's portrait. Unfortunately, the nubile (and oviparous) niece of the high priest takes a liking to him, and when he needs help the price is marriage. Meanwhile he runs into K. Yano (or Chuen), a ship companion who seems to be an Earth agent. They realize they are after the same people -- in Yano's case, because the bad guy is suspected of running guns to Krishna, with the object of making himself the planetary ruler. He has already taken over the island kingdom of Zamba (at last, the title becomes clear!). It is up to Hasselborg and Yano to foil the plot, and then resolve their conflicting requirements re the villains. (And in Hasselborg's case, worry about whether if he brings her husband to justice, his beloved will stay married to him, or ...)

It's certainly a pleasant adventure romp, with plenty of color and light-hearted humor. As SF, it's not really all that inspiring -- it could easily enough have been recast as historical fiction. Victor Hasselborg is enjoyable to follow, though his mixture of competence and what seems at times pasted on foibles and diffidence is not quite convincing. His romance is not too exciting -- the girl behind offstage for almost the entire book. Fun, worth your time, not an enduring classic.

Sunday, August 5, 2018

Friday, August 3, 2018

A Little Known Ace Double: So Bright the Vision, by Clifford D. Simak/The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, by Jeff Sutton

Ace Double Reviews, 70: So Bright the Vision, by Clifford D. Simak/The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, by Jeff Sutton (#H-95, 1968, $0.60)

The Simak half is a collection of not terribly well-known longer stories, from the late 50s basically. The Sutton half is a novel by a very little-known writer. The Simak collection totals 63,000 words, the Sutton novel is about 50,000, making this a fairly long Ace Double.

The four stories collected in So Bright the Vision are "The Golden Bugs" (F&SF, June 1960, 16400 words); "Leg. Forst." (Infinity, April 1958, 17100 words); "So Bright the Vision" (Fantastic Universe, August 1956, 18900 words); and "Galactic Chest" (Science Fiction Stories, September 1956, 10600 words). They are all enjoyable, none really ranks among Simak's best work.

In "The Golden Bugs" a man discovers a strange sort of rock in his back yard, and soon also some very odd insects in his house. Insects that for a short time appear quite helpful ... In "Leg. Forst." an aging con man and stamp collector discovers a remarkable property of a curious stamp he receives from another planet, when said stamp is accidentally mixed with beef broth. The result is marketable as an efficiency enhancer, but it does so in somewhat surprising ways. The conclusion is a little bit unexpected in a sly way. "So Bright the Vision" is probably the best of these stories. It's set in a future in which Earth's only contribution to Galactic society is fiction -- it seems only humans among intelligent races can lie. The necessity to turn out product has led to automation of writing: actually thinking up plots and writing prose by yourself is taboo. A struggling hack gets in trouble with an alien race -- a couple of alien races, in the end. That the resolution will involve the possibility of actual writing, not just programming a writing machine, is predictable from the start, but Simak gets to that point in unexpected ways: and where he ends up isn't quite exactly the cliche ending we might have expected. Finally, "Galactic Chest", as with a number of Simak's stories, involves a newspaperman as protagonist. (Simak of course was a newspaperman himself.) This man is stuck writing the Community Chest column for a local newspaper when he runs a story about "brownies" causing runs of good luck and then realizes to his surprise that the story might actually be true. The solution, again, is mostly what we expect but just slightly different -- I'd say that in three of these four stories ("The Golden Bugs", my least favorite, excepted) the stories are distinguished by a slightly new resolution to a fairly familiar situation.

Jeff Sutton (full name Jefferson Howard Sutton) isn't a terribly well-known writer, but he did publish something in the neighborhood of 20 SF novels between 1959 and his death at the age of 66 in 1979. He also published a few short stories, one of which I read recently in an issue of the very obscure 1950s magazine Spaceways. A number of Sutton's novels were YA books, these written in collaboration with his wife Jean.

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow concerns an mysterious man who appears and suddenly becomes a financial tycoon, based on his uncanny knowledge of the future of the stock market. His vast fortune allows him to wield outsize influence politically, and he soon appears to be trying to control certain foreign countries by means of bribes. This naturally attracts the interest of the US government, which assigns an agent to him. Indeed the book opens with two curious scenes: one is of a mild-mannered mathematician waiting to assassinate a shiftless laborer, the other is of an agent waiting to assassinate the tycoon.

Then the book shifts back in time, following two threads. One concerns the tycoon, his appearance, and his early success, and his curious interest in a certain obscure branch of mathematics. The other concerns the mathematician we met at the opening. He is one of about 6 worldwide experts in the theory of multidimensional space. He is dating a beautiful arts professor, but then he loses her to the tycoon. He also notices that his expert colleagues are dying in mysterious fashion. And soon he seems to be under attack, as well as his friends ...

Well, we can all guess what's going on, I think. But it's resolved reasonably well. It's a surprisingly dark book, actually. It's no better than OK as a whole, and it doesn't really convince in its examination of time paradoxes, but there are some nice bits, and it's competently executed.

The Simak half is a collection of not terribly well-known longer stories, from the late 50s basically. The Sutton half is a novel by a very little-known writer. The Simak collection totals 63,000 words, the Sutton novel is about 50,000, making this a fairly long Ace Double.

|

| (Covers by Jack Gaughan and Gray Morrow) |

The four stories collected in So Bright the Vision are "The Golden Bugs" (F&SF, June 1960, 16400 words); "Leg. Forst." (Infinity, April 1958, 17100 words); "So Bright the Vision" (Fantastic Universe, August 1956, 18900 words); and "Galactic Chest" (Science Fiction Stories, September 1956, 10600 words). They are all enjoyable, none really ranks among Simak's best work.

In "The Golden Bugs" a man discovers a strange sort of rock in his back yard, and soon also some very odd insects in his house. Insects that for a short time appear quite helpful ... In "Leg. Forst." an aging con man and stamp collector discovers a remarkable property of a curious stamp he receives from another planet, when said stamp is accidentally mixed with beef broth. The result is marketable as an efficiency enhancer, but it does so in somewhat surprising ways. The conclusion is a little bit unexpected in a sly way. "So Bright the Vision" is probably the best of these stories. It's set in a future in which Earth's only contribution to Galactic society is fiction -- it seems only humans among intelligent races can lie. The necessity to turn out product has led to automation of writing: actually thinking up plots and writing prose by yourself is taboo. A struggling hack gets in trouble with an alien race -- a couple of alien races, in the end. That the resolution will involve the possibility of actual writing, not just programming a writing machine, is predictable from the start, but Simak gets to that point in unexpected ways: and where he ends up isn't quite exactly the cliche ending we might have expected. Finally, "Galactic Chest", as with a number of Simak's stories, involves a newspaperman as protagonist. (Simak of course was a newspaperman himself.) This man is stuck writing the Community Chest column for a local newspaper when he runs a story about "brownies" causing runs of good luck and then realizes to his surprise that the story might actually be true. The solution, again, is mostly what we expect but just slightly different -- I'd say that in three of these four stories ("The Golden Bugs", my least favorite, excepted) the stories are distinguished by a slightly new resolution to a fairly familiar situation.

Jeff Sutton (full name Jefferson Howard Sutton) isn't a terribly well-known writer, but he did publish something in the neighborhood of 20 SF novels between 1959 and his death at the age of 66 in 1979. He also published a few short stories, one of which I read recently in an issue of the very obscure 1950s magazine Spaceways. A number of Sutton's novels were YA books, these written in collaboration with his wife Jean.

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow concerns an mysterious man who appears and suddenly becomes a financial tycoon, based on his uncanny knowledge of the future of the stock market. His vast fortune allows him to wield outsize influence politically, and he soon appears to be trying to control certain foreign countries by means of bribes. This naturally attracts the interest of the US government, which assigns an agent to him. Indeed the book opens with two curious scenes: one is of a mild-mannered mathematician waiting to assassinate a shiftless laborer, the other is of an agent waiting to assassinate the tycoon.

Then the book shifts back in time, following two threads. One concerns the tycoon, his appearance, and his early success, and his curious interest in a certain obscure branch of mathematics. The other concerns the mathematician we met at the opening. He is one of about 6 worldwide experts in the theory of multidimensional space. He is dating a beautiful arts professor, but then he loses her to the tycoon. He also notices that his expert colleagues are dying in mysterious fashion. And soon he seems to be under attack, as well as his friends ...

Well, we can all guess what's going on, I think. But it's resolved reasonably well. It's a surprisingly dark book, actually. It's no better than OK as a whole, and it doesn't really convince in its examination of time paradoxes, but there are some nice bits, and it's competently executed.

Some of Clifford Simak's Short Fiction

Eternity Lost: The

Collected Stories of Clifford D. Simak, Volume I, by Clifford D. Simak (Darkside Press, 0-9740589-4-7, $40,

3302pp, hc) 2005.

Clifford D. Simak was the third person named a Grand Master

by SFWA, in 1976. He won Hugos for "The Big Front Yard" (1958), Way Station (1963), and "Grotto of

the Dancing Deer" (1980) as well as a Nebula for "Grotto of the

Dancing Deer" and an International Fantasy Award for City. So his credentials as a revered writer in the field are

unchallengeable, and it can't be said that he was not acknowledged during his

lifetime. But it seems to me that, as with some other writers of his

generation, he is in danger of slowly drifting out of the consciousness of SF

readers, especially newer readers. In particular his short fiction is difficult

to find – the current marketplace being so strongly biased towards novels, in

contrast to the situation for the first couple of decades of Simak's career.

Thus Darkside Press's project to bring Simak's short fiction

into print is particularly welcome. (It should be noted that the same house has

published or is planning collections of work by other, generally less

prominent, writers of roughly the same generation: Cleve Cartmill, John

Wyndham, and Daniel F. Galouye among others.) The Simak books are edited by SF

bibliographer extraordinaire Phil Stephenson-Payne, with introductions by John

Pelan and brief story notes by Stephenson-Payne. These books are limited

edition hardcovers, nicely produced with black and white artwork by Allen Koszowski

– a bit pricy, perhaps, but fine products. (Alas, the Simak project stopped after the second volume.)

Unusually, the Simak volumes do not present the stories in

chronological order, nor in any particular thematic organization. Rather, each

volume will apparently be a representative selection of his short stories from

throughout his career. In Eternity Lost the earliest story is "Sunspot

Purge" from 1940, while the latest is "The Observer" from 1972.

There is even a Western, "Way for the Hangtown Rebel!", from 1945.

That said, the bulk of the collection is from the 50s (7 of 12 stories) and

from one magazine, Galaxy (6

stories).

Simak is known most of all as SF's leading pastoralist – he

loved the countryside, and many of his best known works (including the award

winners City, Way Station, and "The Big Front Yard") were to a

considerable extent set in the country, at the same time unequivocally SF. In

this collection only a few stories really fit that template – including the

first three. "How-2" is a satirical piece about a future overtaken by

the "do-it-yourself" spirit, which is then undermined when a

"do-it-yourselfer" builds an experimental robot. "Founding

Father" is a spooky story of an immortal's long journey to another star

system, and the surprise awaiting him after his arrival. The setup is powerful

and evocative, and the creepy ending is truly effective. In

"Kindergarten", a man who has retired to a farm waiting his death

from cancer finds a strange device on his land that seems to give everyone

exactly what they want. Surely this is an alien device – but what do the aliens

want in return? The answer is gently humanistic in the purest Simakian sense.

But there are some strikingly different stories. "Way

for the Hangtown Rebel!" is one, of course, being a Western – not terribly

interesting to my mind, though, as it seemed routine pulp Western work.

"Sunspot Purge", the earliest story, is rather dated too in style of

telling – a wisecracking journalist being the narrator. (To be sure, Simak was

a newspaperman.) The story is distinguished mainly be the unexpectedly dark

ending – it opens simply enough with a rash of suicides, possibly linked to the

sunspot cycle, but it takes a different turn when the newspaperman is sent

forward in time. "The Call From Beyond" is another very pulpy story,

with the protagonist coming to an implausible Pluto, where he finds the remants

of a research team thought dead, and the dangerous discovery they have made.

The most recent stories are "Buckets of Diamonds"

(1969) and "The Observer" (1972). The first is another story told in

a somewhat folksy idiom, with a small-town lawyer defending his wife's raffish

Uncle after he is found with a pail of diamonds and an unaccountably valuable

painting on his person. Of course these treasures are a hint to something SFnal

going on – and again Simak's resolution is a bit unexpected. "The

Observer" is a quiet story of the very far future – not particulary

original but effective in its Simakian tone.

The other stories are a mixed bag. "The Answers"

is another far future story, with an mixed species expedition encountering a

long lost remnant of humanity that seems perhaps to have found "the

answers" to the hard questions of existence. I admit I found the ending

banal. "Jackpot" seems almost an inversion of "Kindergarten",

as a ship of explorers looking for a big find on an alien planet comes across

something quite remarkable – an alien installation, library or school. Can they

make a profit on this? And is it good for humanity? "Carbon Copy" is

another satiric piece, with an interesting central idea: a real estate agent is

approached to lease houses at absurdly low prices. The gimmick is really pretty

clever, though the resolution doesn't quite realize the idea's potential. And

finally the title story, possibly the best story here (unless that is

"Founding Father"), is a sharp tale of a Senator who has had his life

extended for centuries. Life extension is sharply restricted, and he faces the

loss of this privilege as his Party seems to have decided he is no longer

electable. His reaction is a curious combination of desperation and unexpected

moral courage – with a rather ironic result. I found the story quite

thought-provoking, if not always believable.

Simak's Grand Master status was thoroughly deserved. This

collection is a bit unexpected for an opening collection, however – it doesn't

really feature any of his very best stories. It does display a strong writer

working mostly at the middle of his range – the stories are quite enjoyable,

thoughtful, often taking unexpected turns. Thus – a book much worth reading,

and in a way it's refreshing to think that even better stories await.

Birthday Review: Short Fiction of Marc Laidlaw

Marc Laidlaw was born on 3 August 1960. Another damn kid -- almost a year younger than me! He published a number of novels in the '80s and '90s, such as Neon Lotus and Kalifornia. He spent a lot of time in the gaming industry, before retiring a couple of years ago. He's continued to publish short fiction all this time, including a number of collaborations with Rudy Rucker, and a long and satisfying series about a bard with a stone hand named Gorlen and his companion, a gargoyle with a flesh hand named Spar.

For his birthday I decided to, as I've done for some other writers, compile a set of my Locus reviews of his short fiction. So, here goes:

Locus, February 2005

Finally, Marc Laidlaw's "Jane" (Sci Fiction, February 2005) is truly powerful, disturbing, an mysterious. Jane is a girl living in nearly complete isolation with her parents, her two older brothers, and her perpetually hooded younger sister. Then travelers stumble on their house -- and Jane's father takes shocking action, which leads to terrible repercussions. Nothing is fully explained, but the story hints at a momentous back story and an equally momentous future. The characters are darkly driven -- here there is power and tragedy. All in less than 4000 words. (I reprinted this story in one of my very first anthologies, Fantasy, the Best of the Year: 2006 Edition.)

Locus, August 2008

Contrastingly, Marc Laidlaw’s "Childrun" (F&SF, August 2008) is set in a fairly typical fantasy world, and it features his recurring character Gorlen Vizenfirthe, a bard with a stone hand. Here he comes to a remote town where, mysteriously, all the children save one seem to have vanished. And they each seemed to disappear when a visitor came -- which makes his arrival one regarded with suspicion. The resolution is interesting, and the story is engaging.

Locus, March 2009

In F&SF for March 2009 Marc Laidlaw continues his entertaining series about Gorlen, the bard with a stone hand, as Gorlen reaches a city which carved gargoyles -- and which has been much altered as the gargoyles have rebelled. And if Gorlen is human with a stone hand, what sort of gargoyle might he meet?

Locus, November 2013

And "Bemused", by Marc Laidlaw (F&SF, September-October 2013), is another story in his series about the bard Gorlen and the gargoyle Spar, forever linked because Gorlen has a stone hand (Spar's) and Spar a corresponding hand of flesh. Here they visit an eccentric music loving Lord, Ardentine Wollox, where they discover (to Spar's terrible loss) the menacing secret behind (or underneath) the Wollox fortune. These stories are consistently entertaining traditional fantasy, as we see again ...

in the September Lightspeed, with "Bellweather", another fine entry in the series, this time about an encounter in the mountains with an isolated farmer who saves Gorlen's life, only to incur the wrath of the bell-wielding monk from who he fled as a boy. Spar -- increasingly the moral center of the series -- insists that Gorlen and he help the farmer save his child from the vengeful monk. Again -- entertaining and imaginative work.

Locus, July 2014

I guess I'd consider Marc Laidlaw's adventures of the bard Gorlen and the gargoyle Spar not so much a stealth serialization than a true series of stories (admittedly with something of a narrative arc uniting them). In the latest, "Rooksnight" (F&SF, May-June 2014), they deal with a group of "knights" who are attempting to reclaim all of the vast treasure stolen from their mysterious Lord. The fantastical concepts, such as the intelligent rooks and what they are protecting, are pretty neat -- another good adventure fantasy.

Locus, May 2017

In the January-February 2017 F&SF I also quite enjoyed a couple of stories fitting in different ways into the "crime investigation" category. "Wetherfell’s Reef Runics", by Marc Laidlaw, follows used bookstore owner (I was sold already!) Ambrose Salala, as he gets entangled in the mysterious drowning of a man diving near his store in Hawaii. Ambrose had meant to help an old friend of his by selling some books she had come across, but most of them are tat, except for a strange privately produced book called Reef Runics, by W. S. Wetherfell, the man who had drowned. His friend’s no-good son is involved somehow, as he had been the dead man’s guide; and the book itself is dangerously weird, involving Wetherfell’s conviction that he has discovered a powerful "geognostic network" underwater. It’s told in a leisurely and engaging fashion, with convincing (to me) local color, and a plausible sort of shambolic resolution. Fun stuff, and I hope this becomes a series.

Locus, January 2018

F&SF’s November/December 2018 issue features "Stillborne", a significant and as always enjoyable entry in Marc Laidlaw’s Spar/Gorlen series. The two join a caravan to a town where the Philosopher Moths are scheduled for there every seven years mating swarm. There they encounter Gorlen’s long-past lover, Plenth, whom Gorlen taught to play the eduldamer. Their reunion occasions some flashbacks that throw light on Gorlen’s history -- and that of the gargoyle Spar. In the present day they unravel a mystery entangling the Moths and the very popular local drink, as well as dealing with the complications of Plenth’s strange pregnancy. It’s good solid work, illuminating much, and, I suspect, laying the groundwork for a fuller resolution to this fine series.

Locus, May 2018

Marc Laidlaw’s "A Swim and a Crawl" (F&SF, March-April 2018) is about a man who has decided to swim out to sea off Hawaii to commit suicide, and who then decides not to, and makes it back to a curiously changed shore -- good existential, meditative, horror (if that’s what it should be called).

(I admit it was not until compiling this set of reviews that I realized all the Gorlen/Spar stories have single word titles! I believe Marc is working on a novel about the two -- I look forward eagerly to it!)

For his birthday I decided to, as I've done for some other writers, compile a set of my Locus reviews of his short fiction. So, here goes:

Locus, February 2005

Finally, Marc Laidlaw's "Jane" (Sci Fiction, February 2005) is truly powerful, disturbing, an mysterious. Jane is a girl living in nearly complete isolation with her parents, her two older brothers, and her perpetually hooded younger sister. Then travelers stumble on their house -- and Jane's father takes shocking action, which leads to terrible repercussions. Nothing is fully explained, but the story hints at a momentous back story and an equally momentous future. The characters are darkly driven -- here there is power and tragedy. All in less than 4000 words. (I reprinted this story in one of my very first anthologies, Fantasy, the Best of the Year: 2006 Edition.)

Locus, August 2008

Contrastingly, Marc Laidlaw’s "Childrun" (F&SF, August 2008) is set in a fairly typical fantasy world, and it features his recurring character Gorlen Vizenfirthe, a bard with a stone hand. Here he comes to a remote town where, mysteriously, all the children save one seem to have vanished. And they each seemed to disappear when a visitor came -- which makes his arrival one regarded with suspicion. The resolution is interesting, and the story is engaging.

Locus, March 2009

In F&SF for March 2009 Marc Laidlaw continues his entertaining series about Gorlen, the bard with a stone hand, as Gorlen reaches a city which carved gargoyles -- and which has been much altered as the gargoyles have rebelled. And if Gorlen is human with a stone hand, what sort of gargoyle might he meet?

Locus, November 2013

And "Bemused", by Marc Laidlaw (F&SF, September-October 2013), is another story in his series about the bard Gorlen and the gargoyle Spar, forever linked because Gorlen has a stone hand (Spar's) and Spar a corresponding hand of flesh. Here they visit an eccentric music loving Lord, Ardentine Wollox, where they discover (to Spar's terrible loss) the menacing secret behind (or underneath) the Wollox fortune. These stories are consistently entertaining traditional fantasy, as we see again ...

in the September Lightspeed, with "Bellweather", another fine entry in the series, this time about an encounter in the mountains with an isolated farmer who saves Gorlen's life, only to incur the wrath of the bell-wielding monk from who he fled as a boy. Spar -- increasingly the moral center of the series -- insists that Gorlen and he help the farmer save his child from the vengeful monk. Again -- entertaining and imaginative work.

Locus, July 2014

I guess I'd consider Marc Laidlaw's adventures of the bard Gorlen and the gargoyle Spar not so much a stealth serialization than a true series of stories (admittedly with something of a narrative arc uniting them). In the latest, "Rooksnight" (F&SF, May-June 2014), they deal with a group of "knights" who are attempting to reclaim all of the vast treasure stolen from their mysterious Lord. The fantastical concepts, such as the intelligent rooks and what they are protecting, are pretty neat -- another good adventure fantasy.

Locus, May 2017

In the January-February 2017 F&SF I also quite enjoyed a couple of stories fitting in different ways into the "crime investigation" category. "Wetherfell’s Reef Runics", by Marc Laidlaw, follows used bookstore owner (I was sold already!) Ambrose Salala, as he gets entangled in the mysterious drowning of a man diving near his store in Hawaii. Ambrose had meant to help an old friend of his by selling some books she had come across, but most of them are tat, except for a strange privately produced book called Reef Runics, by W. S. Wetherfell, the man who had drowned. His friend’s no-good son is involved somehow, as he had been the dead man’s guide; and the book itself is dangerously weird, involving Wetherfell’s conviction that he has discovered a powerful "geognostic network" underwater. It’s told in a leisurely and engaging fashion, with convincing (to me) local color, and a plausible sort of shambolic resolution. Fun stuff, and I hope this becomes a series.

Locus, January 2018

F&SF’s November/December 2018 issue features "Stillborne", a significant and as always enjoyable entry in Marc Laidlaw’s Spar/Gorlen series. The two join a caravan to a town where the Philosopher Moths are scheduled for there every seven years mating swarm. There they encounter Gorlen’s long-past lover, Plenth, whom Gorlen taught to play the eduldamer. Their reunion occasions some flashbacks that throw light on Gorlen’s history -- and that of the gargoyle Spar. In the present day they unravel a mystery entangling the Moths and the very popular local drink, as well as dealing with the complications of Plenth’s strange pregnancy. It’s good solid work, illuminating much, and, I suspect, laying the groundwork for a fuller resolution to this fine series.

Locus, May 2018

Marc Laidlaw’s "A Swim and a Crawl" (F&SF, March-April 2018) is about a man who has decided to swim out to sea off Hawaii to commit suicide, and who then decides not to, and makes it back to a curiously changed shore -- good existential, meditative, horror (if that’s what it should be called).

(I admit it was not until compiling this set of reviews that I realized all the Gorlen/Spar stories have single word titles! I believe Marc is working on a novel about the two -- I look forward eagerly to it!)

Thursday, August 2, 2018

Old Bestseller: The Water-Babies, by Charles Kingsley

Old Bestseller Review: The Water-Babies, by Charles Kingsley

a review by Rich Horton

Charles Kingsley (1819-1875) was a clergyman in the Church of England and a novelist. He was a Christian Socialist, prominent in his opposition to, for example, child labor, but terribly inconsistent, in particular as he was quite noticeably racist, particularly as concerns Jews, Catholics, and the Irish, but also lots of other people. These general attitudes of course were not uncommon in those days, but Kingsley appears to me to have held them a bit more virulently than some. He was an early supporter of Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution, but to my eye (based on The Water-Babies alone), his ideas about evolution seem a bit simple-minded. Besides The Water-Babies his most famous novel is Westward Ho!, which I passed on as it seemed terribly sad on a quick skim. Shallow of me, I guess.

I'd been meaning to try The Water-Babies for quite a while. It was once an extremely popular children's book, but it has largely faded from notice in recent decades. I found a copy recently at an estate sale, and figured now was the time. My edition probably dates to the 1930s. The book was first serialized in Macmillan's in 1962/1863, and published in book form in 1863. My edition is inscribed "A Happy Birthday to Betty and much love from Benjamin Edwards. May 16-1934. Baghdad." It was published by Thomas Nelson, now well known as an American publisher of most religious material, but back then a more generally focussed English publisher. It is copiously illustrated by Anne Anderson. Anderson (1874-1952) was a Scottish illustrator, mostly of children's books.

The Water-Babies concerns the lives of Tom, who when we first meet him is a chimney sweep in the North Country of England. His master, Grimes, is a cruel man and a drunkard, and Tom can think of little but when he will become a master sweep and be able to treat his apprentices as cruelly as Grimes has treated him. One day Grimes gets as assignment to clean the chimneys of Sir John Harthover, an honorable and highly respected local judge. On the way they meet a mysterious Irishwoman, who objects to Grimes' treatment of Tom, and who tells them "Those that wish to be clean, clean they will be; and those that wish to be foul, foul they will be."

At Harthover Place, Tom manages to get lost in the maze on chimneys, and he ends up coming down into the fireplace of the daughter of the house, Ellie, who is about his age. He is supposed to be a thief, and he is chased out the window and runs away in a panic, making his way across the moors ot a secluded village, where he is treated kindly by a local schoolmarm, but ends up falling in the river and being transformed into a tiny "water baby". Soon after Sir John, having realized that Tom was innocent, organizes a search, and finds the husk of his body, so that he is presumed dead. (Not too long after that, Ellie also dies in a fall, and is herself transformed to a water baby.)

Tom's career as a water baby proceeds -- at first he makes friends with fish and water insects and so on, though he is also often cruel. All along, without his realizing it, fairies are helping him. Eventually he proceeds down river to the sea, and has further adventures and travels, making his way at last to St. Brandan's Isle, where the fairies Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby and Bedonebyasyoudid try to show him a way to be a better person. He meets Ellie there as well, and learns that she goes to someplace special on Sundays. Eventually he is set a task -- to do something he doesn't want to do, and help someone he doesn't like -- and another quest ensues, ending up with him becoming worthy of Ellie, and both becoming human again, and (it seems, though the book denies this in a joking fashion (only princes and princesses get married in fairy tales)) getting married, while Tom becomes an engineer. It's not clear what their identities are in this new incarnation.

I've skipped over the bulk of the book, really, which is amusing descriptions of the lives of various water creatures and birds and so on, along with a number of, essentially, Just So stories. These are often fun, but they are also moralizing to a fault, and twee rather beyond a fault. This isn't a bad book, and I can see the appeal it must have had, but it didn't really work for me, and I can see why it has become largely forgotten.

a review by Rich Horton

Charles Kingsley (1819-1875) was a clergyman in the Church of England and a novelist. He was a Christian Socialist, prominent in his opposition to, for example, child labor, but terribly inconsistent, in particular as he was quite noticeably racist, particularly as concerns Jews, Catholics, and the Irish, but also lots of other people. These general attitudes of course were not uncommon in those days, but Kingsley appears to me to have held them a bit more virulently than some. He was an early supporter of Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution, but to my eye (based on The Water-Babies alone), his ideas about evolution seem a bit simple-minded. Besides The Water-Babies his most famous novel is Westward Ho!, which I passed on as it seemed terribly sad on a quick skim. Shallow of me, I guess.

I'd been meaning to try The Water-Babies for quite a while. It was once an extremely popular children's book, but it has largely faded from notice in recent decades. I found a copy recently at an estate sale, and figured now was the time. My edition probably dates to the 1930s. The book was first serialized in Macmillan's in 1962/1863, and published in book form in 1863. My edition is inscribed "A Happy Birthday to Betty and much love from Benjamin Edwards. May 16-1934. Baghdad." It was published by Thomas Nelson, now well known as an American publisher of most religious material, but back then a more generally focussed English publisher. It is copiously illustrated by Anne Anderson. Anderson (1874-1952) was a Scottish illustrator, mostly of children's books.

The Water-Babies concerns the lives of Tom, who when we first meet him is a chimney sweep in the North Country of England. His master, Grimes, is a cruel man and a drunkard, and Tom can think of little but when he will become a master sweep and be able to treat his apprentices as cruelly as Grimes has treated him. One day Grimes gets as assignment to clean the chimneys of Sir John Harthover, an honorable and highly respected local judge. On the way they meet a mysterious Irishwoman, who objects to Grimes' treatment of Tom, and who tells them "Those that wish to be clean, clean they will be; and those that wish to be foul, foul they will be."

At Harthover Place, Tom manages to get lost in the maze on chimneys, and he ends up coming down into the fireplace of the daughter of the house, Ellie, who is about his age. He is supposed to be a thief, and he is chased out the window and runs away in a panic, making his way across the moors ot a secluded village, where he is treated kindly by a local schoolmarm, but ends up falling in the river and being transformed into a tiny "water baby". Soon after Sir John, having realized that Tom was innocent, organizes a search, and finds the husk of his body, so that he is presumed dead. (Not too long after that, Ellie also dies in a fall, and is herself transformed to a water baby.)

Tom's career as a water baby proceeds -- at first he makes friends with fish and water insects and so on, though he is also often cruel. All along, without his realizing it, fairies are helping him. Eventually he proceeds down river to the sea, and has further adventures and travels, making his way at last to St. Brandan's Isle, where the fairies Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby and Bedonebyasyoudid try to show him a way to be a better person. He meets Ellie there as well, and learns that she goes to someplace special on Sundays. Eventually he is set a task -- to do something he doesn't want to do, and help someone he doesn't like -- and another quest ensues, ending up with him becoming worthy of Ellie, and both becoming human again, and (it seems, though the book denies this in a joking fashion (only princes and princesses get married in fairy tales)) getting married, while Tom becomes an engineer. It's not clear what their identities are in this new incarnation.

I've skipped over the bulk of the book, really, which is amusing descriptions of the lives of various water creatures and birds and so on, along with a number of, essentially, Just So stories. These are often fun, but they are also moralizing to a fault, and twee rather beyond a fault. This isn't a bad book, and I can see the appeal it must have had, but it didn't really work for me, and I can see why it has become largely forgotten.

Birthday Review: Cosmonaut Keep, by Ken MacLeod

Cosmonaut Keep, by Ken MacLeod

A review by Rich Horton

Today is Ken MacLeod's 64th birthday, so in his honor I'm reposting this review I did for my SFF Net newsgroup way back in 2000, when Cosmonaut Keep first appeared. (Some of the references are out of date, no doubt.)

Now as to Cosmonaut Keep. I've rapidly become a huge fan of Ken MacLeod's. His first four novels are all inter-related, representing two alternate branches of a future history which diverged in the middle of the 21st century. They are heavily political in content, and the politics is interesting stuff: a mix of somewhat utopian socialism, somewhat utopian libertarianism, and grittily realpolitik views of a decidedly non-utopian near future with a chaotic mix of extrapolations of all sorts of political trends. The other major thread in those novels was the development of Artificial Intelligence, and in particular its potential dangers for ordinary humans. Indeed, each of MacLeod's first four novels features what could be called a genocide of AI's.

Those are good stuff, but MacLeod was pretty much mining the same vein with them. So it's nice to seem him branching out somewhat with Cosmonaut Keep. This book is set in an entirely different future. Instead of AI's, there are several different species of aliens. And while there is a near future depicted as a realpolitik drenched chaotic mix of extrapolations of political trends (mainly a revitalized Communism versus a reasonable extrapolation of U. S. Capitalism), the political stuff is in more in the background, more of a plot driver than a major focus of discussion. The author who seems most present as an influence on Cosmonaut Keep is Poul Anderson: there are several direct echoes of Andersonian themes, and one or two passages that seem almost stylistic hommages to Anderson.

Like all of MacLeod's books up to this point (except his first), it's told in two timelines. After a mysterious prologue, which only makes sense at the end of the book, we are introduced to Gregor Cairns, a student on the planet Mingulay, and his fellow researchers Elizabeth Harkness and Salasso. Salasso is a saur: an intelligent dinosaur-like being. Elizabeth and Gregor are of different social classes: Elizabeth, it seems, is a "native", while Gregor is a descendant of the "cosmonauts", who arrived at Mingulay some centuries earlier from Earth, in a starship which is now unusable. Soon another starship arrives: this one bearing human traders from Nova Babylonia, traders who in some ways resemble Anderson's Kith (and Heinlein's Traders from Citizen of the Galaxy, and Vinge's Qeng Ho), though their starship is actually controlled by aliens called Krakens, who naturally enough are huge beasts that live in water. Details about this future interstellar civilization, called the "Second Sphere", are slow to be revealed, and I won't reveal much here, but they are neat and clever and intriguing details. At any rate, Gregor soon meets a beautiful trader girl and falls in love: but all this is complicated by questions as to what the traders really want from the people of Mingulay, and what Gregor's family and fellow "cosmonauts" wish to do: the Great Work, and on a personal level, by Elizabeth's concealed love for Gregor.

The second timeline follows a Scotsman named Matt back in the middle of the 21st century. He's a manager of programmers: the actual programmers are either AI's or aging geeks who remember legacy code like DOS and Unix. He's got a thing for an American named Jadey who is involved with the Resistance movement in England: and before long she's giving him a disk with some very interesting information on it. At the same time, an announcement stuns the world: the (Communist) European Union has been contacted by aliens in an asteroid they've been studying. Soon Jadey is under arrest, and Matt is fleeing to Area 51, then to the asteroid, where they learn that the information Jadey had Matt smuggle out is plans for a spaceship and a space drive. All this is highly destabilizing to the world political situation, which teeters on the brink of chaos while the scientists on the asteroid try to talk to the aliens and build the spaceship. It's easy to see where this is going, given that it has to mesh with the other story, but it's still clever and suspenseful.

This is a very good novel, one of the best I've read in 2000. It's got a nice, well-contained story, involving mainly Gregor and Matt's personal lives mixed with the Great Work (for Gregor) and with Matt's obvious destiny. At the same time this story is clearly a setup for potentially fascinating future books in its series. (The title page says this is Book One of Engines of Light.) It's full of nifty SFnal ideas. Behind the scenes, just barely hinted at, are some really scary implications, and some really well-done half-evocations of deep time. (Such as: what has happened on Earth since the starship left for Mingulay?) Much is just sketched in, especially about the multiple-alien interstellar society of the Second Sphere, which will be expanded on, I assume, in future books. MacLeod's prose continues toimprove: he has a habit of mostly just writing sound, clever, workable stuff, then every so often winding up to an emotional and even quasi-poetic peak. The characters are decently drawn, though not especially deep, and there is a certain sense that their romantic lives are resolved rather conveniently. (Which isn't to say necessarily happily.) Mostly, this is just good solid Science Fiction, with plenty of sense of wonder inducing ideas.

A review by Rich Horton

Today is Ken MacLeod's 64th birthday, so in his honor I'm reposting this review I did for my SFF Net newsgroup way back in 2000, when Cosmonaut Keep first appeared. (Some of the references are out of date, no doubt.)

|

| (Cover by Stephen Martiniere) |

Those are good stuff, but MacLeod was pretty much mining the same vein with them. So it's nice to seem him branching out somewhat with Cosmonaut Keep. This book is set in an entirely different future. Instead of AI's, there are several different species of aliens. And while there is a near future depicted as a realpolitik drenched chaotic mix of extrapolations of political trends (mainly a revitalized Communism versus a reasonable extrapolation of U. S. Capitalism), the political stuff is in more in the background, more of a plot driver than a major focus of discussion. The author who seems most present as an influence on Cosmonaut Keep is Poul Anderson: there are several direct echoes of Andersonian themes, and one or two passages that seem almost stylistic hommages to Anderson.

Like all of MacLeod's books up to this point (except his first), it's told in two timelines. After a mysterious prologue, which only makes sense at the end of the book, we are introduced to Gregor Cairns, a student on the planet Mingulay, and his fellow researchers Elizabeth Harkness and Salasso. Salasso is a saur: an intelligent dinosaur-like being. Elizabeth and Gregor are of different social classes: Elizabeth, it seems, is a "native", while Gregor is a descendant of the "cosmonauts", who arrived at Mingulay some centuries earlier from Earth, in a starship which is now unusable. Soon another starship arrives: this one bearing human traders from Nova Babylonia, traders who in some ways resemble Anderson's Kith (and Heinlein's Traders from Citizen of the Galaxy, and Vinge's Qeng Ho), though their starship is actually controlled by aliens called Krakens, who naturally enough are huge beasts that live in water. Details about this future interstellar civilization, called the "Second Sphere", are slow to be revealed, and I won't reveal much here, but they are neat and clever and intriguing details. At any rate, Gregor soon meets a beautiful trader girl and falls in love: but all this is complicated by questions as to what the traders really want from the people of Mingulay, and what Gregor's family and fellow "cosmonauts" wish to do: the Great Work, and on a personal level, by Elizabeth's concealed love for Gregor.

The second timeline follows a Scotsman named Matt back in the middle of the 21st century. He's a manager of programmers: the actual programmers are either AI's or aging geeks who remember legacy code like DOS and Unix. He's got a thing for an American named Jadey who is involved with the Resistance movement in England: and before long she's giving him a disk with some very interesting information on it. At the same time, an announcement stuns the world: the (Communist) European Union has been contacted by aliens in an asteroid they've been studying. Soon Jadey is under arrest, and Matt is fleeing to Area 51, then to the asteroid, where they learn that the information Jadey had Matt smuggle out is plans for a spaceship and a space drive. All this is highly destabilizing to the world political situation, which teeters on the brink of chaos while the scientists on the asteroid try to talk to the aliens and build the spaceship. It's easy to see where this is going, given that it has to mesh with the other story, but it's still clever and suspenseful.

This is a very good novel, one of the best I've read in 2000. It's got a nice, well-contained story, involving mainly Gregor and Matt's personal lives mixed with the Great Work (for Gregor) and with Matt's obvious destiny. At the same time this story is clearly a setup for potentially fascinating future books in its series. (The title page says this is Book One of Engines of Light.) It's full of nifty SFnal ideas. Behind the scenes, just barely hinted at, are some really scary implications, and some really well-done half-evocations of deep time. (Such as: what has happened on Earth since the starship left for Mingulay?) Much is just sketched in, especially about the multiple-alien interstellar society of the Second Sphere, which will be expanded on, I assume, in future books. MacLeod's prose continues toimprove: he has a habit of mostly just writing sound, clever, workable stuff, then every so often winding up to an emotional and even quasi-poetic peak. The characters are decently drawn, though not especially deep, and there is a certain sense that their romantic lives are resolved rather conveniently. (Which isn't to say necessarily happily.) Mostly, this is just good solid Science Fiction, with plenty of sense of wonder inducing ideas.

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

Birthday Review: I Dare, by Sharon Lee and Steve Miller

I Dare, by Sharon Lee and Steve Miller, Meisha Merlin, Decatur, GA, 2002, ISBN 1-892065-03-7, US$18.00, 472 pages

A review by Rich Horton

Steve Miller was born on July 31, 1950, and so I decided to resurrect this review I did for 3SF back in 2002. It's a fairly brief review, conforming to the format I used for 3SF.

[I should note that my favorite Liaden novels are a pair of books set a generation before the main plot line which was started in the first book (Agent of Change) and concluded in the book reviewed here, I Dare. Those books are Local Custom and Scout's Progress, books written in the early '90s but not published until 2001 by Meisha Merlin, and 2002 by Ace. Both have significant romance plots (unlike most of the Liaden books, which are more adventure oriented), and I really enjoyed them. I reviewed them for Dave Felts' small 'zine Maelstrom, but I've lost my copies of those reviews. (I have the Maelstrom issues somewhere, and maybe I'll retype them from the paper copies whenever I find them.)]

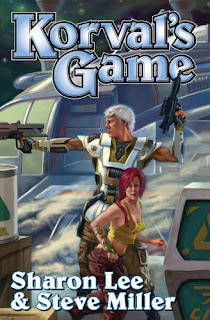

I will also add that Lee and Miller now publish with Baen, and I Dare and its immediate predecessor, Plan B, have been republished by Baen as Korval's Game.

Sharon Lee and Steve Miller published their first Liaden books in 1989. The series was picked up by Meisha Merlin and continued in 1999. I Dare is the seventh novel, and it ends the long plot arc begun in the first book, though there is plenty of room for further books in the same universe.

This book follows Plan B, in which the powerful but controversial Clan Korval was forced by the machinations of the sinister Department of the Interior to abandon the Liaden main world, Liad. The current novel follows several threads. On the planet Erob, many of the main Korval Clan members are gathering to muster a force that can resist the Department, while back on Liad the wizard Anthora tries to maintain the home front. But Anthora may be getting help from an unexpected source … And the somewhat raffish gambler, Pat Rin, has been isolated from the rest of the Clan, and he gathers a beautiful gangster and some more friends and tries to set up another power base on an isolated, rather anarchic, world.

As the above summary might suggest, the book is rather busy, probably too much so. I think it could have benefited from judicious cutting, perhaps the complete excision of at least one thread. The authors also give the good guys such power (essentially magical powers) that too much suspense is leached from the conflict – they cannot lose. It's still exciting. I liked the sections with Pat Rin particularly. As usual, there is a heavy dose of romance to go along with plenty of action. It's by no means the best of the Liaden novels, and it's not a good place to start, but I Dare does resolve longstanding questions, and is should satisfy long time fans.

A review by Rich Horton

Steve Miller was born on July 31, 1950, and so I decided to resurrect this review I did for 3SF back in 2002. It's a fairly brief review, conforming to the format I used for 3SF.

[I should note that my favorite Liaden novels are a pair of books set a generation before the main plot line which was started in the first book (Agent of Change) and concluded in the book reviewed here, I Dare. Those books are Local Custom and Scout's Progress, books written in the early '90s but not published until 2001 by Meisha Merlin, and 2002 by Ace. Both have significant romance plots (unlike most of the Liaden books, which are more adventure oriented), and I really enjoyed them. I reviewed them for Dave Felts' small 'zine Maelstrom, but I've lost my copies of those reviews. (I have the Maelstrom issues somewhere, and maybe I'll retype them from the paper copies whenever I find them.)]

I will also add that Lee and Miller now publish with Baen, and I Dare and its immediate predecessor, Plan B, have been republished by Baen as Korval's Game.

Sharon Lee and Steve Miller published their first Liaden books in 1989. The series was picked up by Meisha Merlin and continued in 1999. I Dare is the seventh novel, and it ends the long plot arc begun in the first book, though there is plenty of room for further books in the same universe.

This book follows Plan B, in which the powerful but controversial Clan Korval was forced by the machinations of the sinister Department of the Interior to abandon the Liaden main world, Liad. The current novel follows several threads. On the planet Erob, many of the main Korval Clan members are gathering to muster a force that can resist the Department, while back on Liad the wizard Anthora tries to maintain the home front. But Anthora may be getting help from an unexpected source … And the somewhat raffish gambler, Pat Rin, has been isolated from the rest of the Clan, and he gathers a beautiful gangster and some more friends and tries to set up another power base on an isolated, rather anarchic, world.

As the above summary might suggest, the book is rather busy, probably too much so. I think it could have benefited from judicious cutting, perhaps the complete excision of at least one thread. The authors also give the good guys such power (essentially magical powers) that too much suspense is leached from the conflict – they cannot lose. It's still exciting. I liked the sections with Pat Rin particularly. As usual, there is a heavy dose of romance to go along with plenty of action. It's by no means the best of the Liaden novels, and it's not a good place to start, but I Dare does resolve longstanding questions, and is should satisfy long time fans.

Saturday, July 28, 2018

Birthday Review: Kalpa Imperial (and Trafalgar), by Angélica Gorodischer

Kalpa Imperial: The Greatest Empire That Never Was, by Angélica Gorodischer, translated by Ursula K. Le Guin (Small Beer Press, 2003)

A review by Rich Horton

[Angélica Gorodischer turns 90 today, and in honor of her birthday, I'm posting this review I did for Locus Online back in 2003, and I've added the snippet I wrote about her book Trafalgar for Locus (the print version) in 2013. The original Locus Online review of Kalpa Imperial is here.]

Here before me is a delightful book, Kalpa Imperial, by Angélica Gorodischer. It is a fantasy about "The Greatest Empire That Never Was", as the subtitle has it. Gorodischer is Argentine, and the translation from the Spanish is by Ursula K. Le Guin -- a recommendation in itself! A portion of this book was published in Starlight 2 a few years ago. The voice seems very reminiscent of Le Guin: hard to say if that's reflective of the original work or of her translation.

The book is a compendium of several separate stories, mostly told by a professional storyteller (who also has an important additional role in one story), concerning the history of "The Greatest Empire That Never Was". Most of the stories tell of Emperors and Empresses, some good, some bad, some mad -- how they came to power, how they fell from power, how they ruled. The stories are often romantic, but the romanticism is tinged by a sort of earthiness, and a realism that does not quite become cynical. The stories are nicely imagined, sometimes funny, sometimes brutal. The whole is billed as a novel, but the stories work fine separately, and are really linked only by geography and the voice of the storyteller, so it's more a linked collection of short fiction, in my view.

There are eleven stories, or chapters, arranged in two books. The opening piece, "Portrait of the Emperor", tells us that a good man now sits on the throne of the Empire, and then goes on to tell of the founding of the empire, by a weakling boy who learned a different kind of strength. "The Two Hands" is a fable-like story of an usurper who ended up spending twenty years confined in his bedroom. "The End of a Dynasty, or The Natural History of Ferrets" tells of a young Crown Prince, son of a cruel Empress and a deposed Emperor, who grows up torn between the evil influence of his mother and the countervailing touch of a couple of kindly workmen. "Siege, Battle, and Victory of Selimmagud" is an ironic tale of a thief and deserter and his encounter with the General besieging the title city. "Concerning the Unchecked Growth of Cities" is a lovely long description of the varying history of a Northern city, sometimes the capitol, sometimes ignored, sometimes something quite else.

Book two opens with "Portrait of the Empress", in which the storyteller who has been narrating these tales is recruited by the Great Empress to tell her of her Empire's history. She in turn tells him of the woman who rose from poverty to become the Great Empress. "And the Streets Empty" is a dark story of the vengeful destruction of a city by a jealous Empress. "The Pool" concerns a mysterious physician, and his encounters with those plotting to overturn the current dynasty. "Basic Weapons" is a colorful and macabre piece about a dealer in people, and a rich man, and obsession. "'Down There in the South'" is a long story of an aristocrat with a dark secret who is forced to flee from the ruling North to the rural South, and who is fated to change history when the North comes to invade. And "The Old Incense Road" tells of a mysterious orphan, a mysterious merchant, a caravan, and some "stories within the story", all eventually concerning another change of rulers.

The stories are full of humor and tragedy, of cynicism and romanticism, of secret identities, of wisdom and folly, of blood, of nobility. The fantastical elements are slim: this is perhaps what is called sometimes "Ruritanian" fantasy -- set in a different world that much resembles ours. At the same time the landscapes and characters and events are heightened in color, so that if there may not be overt magic, the ordinary seems magic enough. The feel is certainly fantastical.

It is often remarked that Americans (indeed, English language readers in general) tend not to read a lot of fiction in translation. This does seem true of SF readers -- we are happy enough to read books by Englishmen and Australians and even those wacky Canadians, but it tends to be hard to find books from other languages. I'm not sure this is entirely, or even largely, because Americans (or Englishmen or Australians or whomever) are particularly xenophobic. Rather, there isn't that much available in translation, for several reasons. Acquiring a foreign language book means the publisher (or author) must pay extra for a translator. Once translated the book is different from the original -- most likely not as good. (And a bad translation can do long-term harm, in part by making it harder still to obtain a good translation. (I have heard that the English publishers of Stanislaw Lem's Solaris have refused to contract for a new translation, even of such an important novel, even though the existing one is notoriously poor (apparently a two step job, Polish to French to English).)) Finally, the English language book market is pretty full of books in English -- perhaps publishers simply feel there are already enough books. (Perhaps in smaller countries there might be more pressure to find books published in other languages -- assuming the readers have the same appetite for fiction, but fewer writers to provide it.)

But even if our failure to read much SF in translation is understandable, it is nothing to be happy about. Thus I'm delighted to have a chance to praise a book from an Argentine writer. And I'm delighted that the translation reads wonderfully -- though to be sure I cannot speak directly to its accuracy. Kalpa Imperial is a lovely book -- praise is due Le Guin and to the folks at Small Beer Press for bringing it to our attention; and much praise is due Angélica Gorodischer for writing it.

[Added in 2018]

Happily, the amounted of translated SF available in the US has expanded tremendously, most notably evidence by Hugos for China's Cixin Liu and Hao Jingfang and for Dutch writer Thomas Olde Heuvelt. Indeed, short fiction in translation is a regular feature in magazines like Clarkesworld. As for Gorodischer, at least one more of her books has been translated into English, also SF: Trafalgar, back in 2013. Here's what I wrote about that book in the May 2013 Locus:

A few years ago Small Beer Press published the Argentine writer Angélica Gorodischer's lovely mosaic novel (or linked story collection) Kalpa Imperial (translated by Ursula K. Le Guin). Now they give us another linked collection from Gorodischer, Trafalgar. (This time Amalia Gladhart does the translation.) The stories are all about a merchant named Trafalgar Medrano, who has a spaceship he calls the Clunker, and who travels all around the Galaxy buying and selling things, and more importantly, encountering strange planets and stranger societies. There is a sort of club story feeling to the tales -- almost a resemblance to Dunsany's Jorkens -- and there is also a hint of Le Guin in the ethnography. The book is enjoyable throughout -- Trafalgar's voice is absorbing, and so is that of the narrator (who may or may not be the same person throughout) -- and the societies Trafalgar encounters are interesting and wittily presented. My favorite was "Trafalgar and Josefina", a tale told to the narrator through her somewhat eccentric old Aunt Josefina, very very funny in its framing (that is, in Josefina's comments on the story) and turning darker as we learn of Trafalgar's visit to a planet with a very strict caste system, ruled by a randomly chosen person of a lower caste, who makes the mistake of falling for a married woman.

A review by Rich Horton

[Angélica Gorodischer turns 90 today, and in honor of her birthday, I'm posting this review I did for Locus Online back in 2003, and I've added the snippet I wrote about her book Trafalgar for Locus (the print version) in 2013. The original Locus Online review of Kalpa Imperial is here.]

Here before me is a delightful book, Kalpa Imperial, by Angélica Gorodischer. It is a fantasy about "The Greatest Empire That Never Was", as the subtitle has it. Gorodischer is Argentine, and the translation from the Spanish is by Ursula K. Le Guin -- a recommendation in itself! A portion of this book was published in Starlight 2 a few years ago. The voice seems very reminiscent of Le Guin: hard to say if that's reflective of the original work or of her translation.

The book is a compendium of several separate stories, mostly told by a professional storyteller (who also has an important additional role in one story), concerning the history of "The Greatest Empire That Never Was". Most of the stories tell of Emperors and Empresses, some good, some bad, some mad -- how they came to power, how they fell from power, how they ruled. The stories are often romantic, but the romanticism is tinged by a sort of earthiness, and a realism that does not quite become cynical. The stories are nicely imagined, sometimes funny, sometimes brutal. The whole is billed as a novel, but the stories work fine separately, and are really linked only by geography and the voice of the storyteller, so it's more a linked collection of short fiction, in my view.

There are eleven stories, or chapters, arranged in two books. The opening piece, "Portrait of the Emperor", tells us that a good man now sits on the throne of the Empire, and then goes on to tell of the founding of the empire, by a weakling boy who learned a different kind of strength. "The Two Hands" is a fable-like story of an usurper who ended up spending twenty years confined in his bedroom. "The End of a Dynasty, or The Natural History of Ferrets" tells of a young Crown Prince, son of a cruel Empress and a deposed Emperor, who grows up torn between the evil influence of his mother and the countervailing touch of a couple of kindly workmen. "Siege, Battle, and Victory of Selimmagud" is an ironic tale of a thief and deserter and his encounter with the General besieging the title city. "Concerning the Unchecked Growth of Cities" is a lovely long description of the varying history of a Northern city, sometimes the capitol, sometimes ignored, sometimes something quite else.

Book two opens with "Portrait of the Empress", in which the storyteller who has been narrating these tales is recruited by the Great Empress to tell her of her Empire's history. She in turn tells him of the woman who rose from poverty to become the Great Empress. "And the Streets Empty" is a dark story of the vengeful destruction of a city by a jealous Empress. "The Pool" concerns a mysterious physician, and his encounters with those plotting to overturn the current dynasty. "Basic Weapons" is a colorful and macabre piece about a dealer in people, and a rich man, and obsession. "'Down There in the South'" is a long story of an aristocrat with a dark secret who is forced to flee from the ruling North to the rural South, and who is fated to change history when the North comes to invade. And "The Old Incense Road" tells of a mysterious orphan, a mysterious merchant, a caravan, and some "stories within the story", all eventually concerning another change of rulers.

The stories are full of humor and tragedy, of cynicism and romanticism, of secret identities, of wisdom and folly, of blood, of nobility. The fantastical elements are slim: this is perhaps what is called sometimes "Ruritanian" fantasy -- set in a different world that much resembles ours. At the same time the landscapes and characters and events are heightened in color, so that if there may not be overt magic, the ordinary seems magic enough. The feel is certainly fantastical.

It is often remarked that Americans (indeed, English language readers in general) tend not to read a lot of fiction in translation. This does seem true of SF readers -- we are happy enough to read books by Englishmen and Australians and even those wacky Canadians, but it tends to be hard to find books from other languages. I'm not sure this is entirely, or even largely, because Americans (or Englishmen or Australians or whomever) are particularly xenophobic. Rather, there isn't that much available in translation, for several reasons. Acquiring a foreign language book means the publisher (or author) must pay extra for a translator. Once translated the book is different from the original -- most likely not as good. (And a bad translation can do long-term harm, in part by making it harder still to obtain a good translation. (I have heard that the English publishers of Stanislaw Lem's Solaris have refused to contract for a new translation, even of such an important novel, even though the existing one is notoriously poor (apparently a two step job, Polish to French to English).)) Finally, the English language book market is pretty full of books in English -- perhaps publishers simply feel there are already enough books. (Perhaps in smaller countries there might be more pressure to find books published in other languages -- assuming the readers have the same appetite for fiction, but fewer writers to provide it.)

But even if our failure to read much SF in translation is understandable, it is nothing to be happy about. Thus I'm delighted to have a chance to praise a book from an Argentine writer. And I'm delighted that the translation reads wonderfully -- though to be sure I cannot speak directly to its accuracy. Kalpa Imperial is a lovely book -- praise is due Le Guin and to the folks at Small Beer Press for bringing it to our attention; and much praise is due Angélica Gorodischer for writing it.

[Added in 2018]

Happily, the amounted of translated SF available in the US has expanded tremendously, most notably evidence by Hugos for China's Cixin Liu and Hao Jingfang and for Dutch writer Thomas Olde Heuvelt. Indeed, short fiction in translation is a regular feature in magazines like Clarkesworld. As for Gorodischer, at least one more of her books has been translated into English, also SF: Trafalgar, back in 2013. Here's what I wrote about that book in the May 2013 Locus:

A few years ago Small Beer Press published the Argentine writer Angélica Gorodischer's lovely mosaic novel (or linked story collection) Kalpa Imperial (translated by Ursula K. Le Guin). Now they give us another linked collection from Gorodischer, Trafalgar. (This time Amalia Gladhart does the translation.) The stories are all about a merchant named Trafalgar Medrano, who has a spaceship he calls the Clunker, and who travels all around the Galaxy buying and selling things, and more importantly, encountering strange planets and stranger societies. There is a sort of club story feeling to the tales -- almost a resemblance to Dunsany's Jorkens -- and there is also a hint of Le Guin in the ethnography. The book is enjoyable throughout -- Trafalgar's voice is absorbing, and so is that of the narrator (who may or may not be the same person throughout) -- and the societies Trafalgar encounters are interesting and wittily presented. My favorite was "Trafalgar and Josefina", a tale told to the narrator through her somewhat eccentric old Aunt Josefina, very very funny in its framing (that is, in Josefina's comments on the story) and turning darker as we learn of Trafalgar's visit to a planet with a very strict caste system, ruled by a randomly chosen person of a lower caste, who makes the mistake of falling for a married woman.

Thursday, July 26, 2018

Birthday Review: A Young Man Without Magic, by Lawrence Watt-Evans

A Young Man Without Magic, by Lawrence Watt-Evans (Tor, 2009)

a review by Rich Horton

Today is Lawrence Watt Evans' 64th birthday, so it seems appropriate to repost this review of a novel I really enjoyed a few years ago. Alas, the series this book started was canceled after the second volume.

Lawrence Watt-Evans' 2009 novel is A Young Man Without Magic. It is the first of a pair* -- not that Tor tells us that, as is too often their habit. It does end dramatically, and at a logical stopping point, but the story certainly isn't over. (And I really wanted to have the next book right then to continue reading!)

(*Actually, I believe seven novels were originally planned, but the publisher dropped the series after the second book.)