(I'm reposting this old Ace Double review on April 9 because that was George O. Smith's birthday.)

Here's an Ace Double from the '50s, featuring two pretty popular writers of that time. Damon Knight, of course, was the more important figure, and his work is lasting. Smith made an impact in the '40s with the Venus Equilateral stories, about a Solar System wide communications relay (and eventually a matter transmission system), which I frankly find unreadable today. He also wrote some more respected novels later on, including The Fourth "R". Smith was born in 1911 in Chicago, attended the University of Chicago. He was an engineer, working at IT&T from when he mostly ceased writing in 1959 until 1974. Somewhat notoriously, he had an affair with John Campbell's wife Dona (source of Campbell's pseudonym "Don A. Stuart"), and they married after each divorced their first spouse. He was given the First Fandom award at the 1980 Worldcon (amusingly, his New York Times obituary misread that detail, and credited him with getting the very first "Fandom Award").

As for Damon Knight, he was born in 1922 in Oregon and died in 2002. He was a prominent fan beginning as early as age 11, and was a member of the influential early fan group the Futurians. He was an illustrator in the '40s, writing a few short stories but becoming far more prolific by the late '40s, and beginning to produce major work in the '50s. His great stories include "The Country of the Kind", "Masks", "Fortyday", "I See You", "Four in One", and particularly a number of great novellas, first among them in my opinion "The Earth Quarter", but also "Rule Golden", "Double Meaning", and "Dio". His early novels were less successful, but he improved over time, and his last two novels, Why Do Birds (1992) and Humpty Dumpty: An Oval (1996), are quite remarkable. But that barely scratches the surface of his contributions: he was a major editor (of magazines like If and Worlds Beyond, and more importantly of the original anthology series Orbit; not to mention numerous excellent reprint anthologies), he was a significant critic, known best for In Search of Wonder, and he was the founding force behind SFWA, as well as the famous Milford writers' workshop. He was married three times, the last time, for the last 39 years of his life, to the great writer Kate Wilhelm (who died recently).

It's always worthwhile looking at the Science Fiction Encylopedia entries for writers, here are those for George O. Smith, and for Damon Knight.

|

| (Cover by Ed Emshwiller) |

In Masters of Evolution the world is divided into city dwellers and "muckfeet". The city dwellers rely on high technology. They are conditioned to fear and feel sick at the thought of country life, and of muckfeet food and hygiene. They have previously fought wars, which both sides claim to have won: but as there are only 22 remaining cities in the whole world, and the muckfeet control the rest of the area, and have a much higher population, the real winners seem obvious.

As the book opens, the Mayor of New York has a desperate idea. He assigns a leading actor, Alvah Gustad, to fly out to the muckfeet and offer to trade with them: the high tech city products in exchange for much needed metals -- and also in the hopes of converting the muckfeet to city ways. Alvah somewhat reluctantly and fearfully makes his way to the country. At first he is confronted with suspicion and threats, or is just ignored. But finally he is given a chance to sell his wares at a fair somewhere in the Midwest. Much to his surprise, nobody is remotely interested in his products -- and worse, after he gets into a scuffle, he finds that the muckfeet have managed to completely disable his energy sources. He is stranded.

A pretty young woman named B. J. and a wise mentor type named Doc Bither take Alvah under their arms, and over some weeks they manage to overcome his conditioning against muckfeet food and smells. We get a look at the muckfeet way of life, which is based on using spectacular products of genetic engineering in place of machines. For example, for airplanes they use "rocs" -- huge flying lizards. Plants are used to extract metals from the ground. Other animals are used as truck or as message devices or as "libraries". Alvah is still reluctant to become a muckfoot, though -- he is still loyal to New York. But he is also in love with B. J. And when the cities launch an attack on the muckfeet, Alvah realizes that many things he has long believed are false. The novel is resolved in a predictable confrontation between Alvah's new friends and his old city.

This is a decent piece of work, enjoyable enough, but lesser work than Knight's best. I would rank it third of his three Ace Doubles (not counting the story collection). Some of the plot contrivances just don't convince -- such as Alvah and the very first muckfoot girl he meets falling in love. And Knight's case for the "natural state" versus "technology" is grossly loaded -- the cities' high tech is burdened by having to comply with the laws of physics, basically, which don't really seem to affect the muckfeet genetic creations. Or put another way -- Knight imagines a utopian perfection of genetic engineering, with limited costs; but the opposing high technology is auctorially declared to be inferior -- but not proven so.

(I also looked at the differences between the original novella and the expanded Ace Double. They consist of a brief passage, about a page, in the middle of the book which explains some of the genetic engineering; and a long additional sequence right at the end, extending the final conflict and giving Alvah a chance to be an action hero of sorts. On the whole, the additions are padding, though I think the explanatory passage fits fine.)

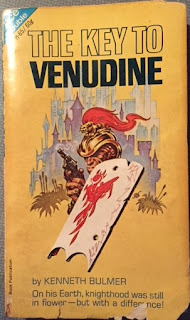

The cover of Fire in the Heavens features a spaceship pulling a string of sailing ships through interplanetary space. I assumed that was just a piece of artistic license -- the artist fancifully depicting the theme of the book. I was wrong -- the cover is a fairly accurate representation of an actual scene! That should tell you just how hokey this novel is.

The hero of the novel is Jeff Benson, a brilliant young physicist who runs a company making scientific instruments. (I thought it significant that Benson is a physicist but is portrayed as an engineer, someone whose main job is putting stuff together.) He runs afoul of the beautiful but amoral Lucille Roman, who runs a sort of megacorporation. Jeff's acquaintance with Charles Horne, one of Lucille's rivals, is enough to convince Lucille that he is in cahoots against her. Lucille's company has developed a new atomic jet, the Roman Jet, but her chief physicist doesn't understand how it works. But Lucille is unwilling to trust Jeff to work with her company. And Jeff is too naive to realize that Charles Horne is as amoral as Lucille.

Jeff has a theory that conservation of mass/energy is not absolute -- that some energy is lost, perhaps into a different universe, whenever any energy is used. When the Roman Jet is tested on a spaceship, the sun is noticed to become unstable. The Jet is blamed for this (through the connivance of Horne), but Jeff's theory offers an alternate explanation. Either way, though, the Sun seems likely to go nova.

Horne hatches a plot to steal Lucille's spaceship and fly to Procyon. For supplies he uses the spaceship to yank a number of cargo ships into space (hence the cover!) Meanwhile Jeff has found a way to use a variation of the Roman Jet to contact other universes. And Lucille is on the run from lynch mobs who believe she has caused the impending nova ...

It's all really too too silly. Surely Smith knew this! And there also cliches such as the beautiful and amoral and sexually loose (it is implied, not shown) woman turning into mush and falling in love with the innocent and virtuous hero. And the plot is discursive and casual and just kind of dumb. Not a very good book at all.

And, finally -- the cover of the July 1949 issue of Startling Stories, by Earle Bergey, needs to be shown: