My final (I trust) organizing post lists the posts I've made about what I consider for the purposes of this blog to be "Old Bestsellers". In its simplest sense I mean books that were on bestseller lists in roughly the first half of the 20th Century, but I extend things to include books by writers who had major bestsellers, and bestselling books from somewhat earlier (at least to the middle of the 19th Century) and a bit later, and occasionally books of a popular sort, in the right time frame, that were by a writer who never quite made it big.

As this sort of book was the first inspiration for this blog, such books make up the largest portion of posts here. (Granted, I stretch a point in including certain books here, but so be it.) So this will be a longish (and ever-growing) list. As of now, there are 94 entries on the list. The best book here is certainly Edith Wharton's The House of Mirth, and the worst is undoubtedly the pirated Count of Monte Cristo faux-sequel Edmund Dantes, by Edmund Flagg.

The Social Secretary, by David Graham Phillips (1905);

The Auction Block, by Rex Beach (1914);

That Girl From New York, by Allene Corliss (1932);

Under the Red Robe, by Stanley J. Weyman (1894);

The Octangle, by Emanie Sachs (1930);

The Lonely, by Paul Gallico (1947);

Under the Rose, by Frederic S. Isham (1903);

The Road to Frontenac, by Samuel Merwin (1901);

The Leopard Woman, by Stewart Edward White (1916);

Castle Garac, by Nicholas Monsarrat (1955);

Rodney Stone, by A. Conan Doyle (1896);

Casuals of the Sea, by William McFee (1916);

The Fortune Hunter, by Louis Joseph Vance (1910);

Penrod, by Booth Tarkington (1914);

Within the Law, by Bayard Veiller (and Marvin Dana) (1913);

She Painted her Face, by Dornford Yates (1936);

The Helmet of Navarre, by Bertha Runkle (1900);

By the Good Sainte-Anne, by Anna Chapin Ray (1904);

Tides, by Ada and Julian Street (1926);

The Siege of the Seven Suitors, by Meredith Nicholson (1910);

Guard Your Daughters, by Diana Tutton (1953);

The Visits of Elizabeth, by Elinor Glyn (1900);

Their Husbands' Wives, edited by William Dean Howells and Henry Mills Alden (1906);

The Blue Flower, by Henry Van Dyke (1902);

Favorite Stories by Famous Writers, edited by Harry Payne Brennan (1932);

Stamboul Nights, by H. G. Dwight (1916);

Black Rock, by Ralph Connor (1899);

The Romantic Comedians, by Ellen Glasgow (1926);

The City of Lilies, by Anthony Pryde and R. K. Weekes (1923);

Coronation Summer, by Angela Thirkell (1952);

Peter, by F. Hopkinson Smith (1908);

Two Black Sheep, by Warwick Deeping (1933);

The Perfume of the Lady in Black, by Gaston Leroux (1909);

The Van Roon, by J. C. Snaith (1922);

Enchanting and Enchanted, by Friedrich Wilhelm Hacklander (1870);

The House of Mirth, by Edith Wharton (1905);

The Morals of Marcus Ordeyne, by William J. Locke (1905);

Marietta, by F. Marion Crawford (1901);

The Count's Millions, by Emile Gaboriau (1870);

Dora Thorne, by Charlotte Mary Brame (1871);

The Vanishing Point, by Coningsby Dawson (1922);

The Maid of Maiden Lane, by Amelia E. Barr (1900);

Guys and Dolls, by Damon Runyon (1932);

The New Arabian Nights, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1882);

Ellen Adair, by Frederick Niven (1913);

The Lion's Share, by Octave Thanet (1907);

Love Insurance, by Earl Derr Biggers (1914);

Bound to Rise, by Horatio Alger, Jr. (1872);

I Love You, I Love You, I Love You, by Ludwig Bemelmans (1942);

The King's General, by Daphne du Maurier (1946);

The Great Impersonation, by E. Phillips Oppenheim (1920);

Piccadilly Jim, by P. G. Wodehouse (1916);

Stormswift, by Madeleine Brent (1984);

Edmund Dantes, by "Alexander Dumas" (1878);

A Princess of Mars, by Edgar Rice Burroughs (1912);

Finnley Wren, by Philip Wylie (1934);

When Knighthood Was in Flower, by "Edwin Caskoden" (Charles Major) (1898);

The Bondage of Ballinger, by Roswell Field (1903);

The Adventures of Richard Hannay, by John Buchan (1915-1919);

A Fool There Was, by Porter Emerson Browne (1909);

The Sheik, by E. M. Hull (1919);

Duchess Hotspur, by Rosamond Marshall (1946);

Random Harvest, by James Hilton (1941);

The Night Life of the Gods, by Thorne Smith (1931);

The Black Flemings, by Kathleen Norris (1926);

Princess Maritza, by Percy Brebner (1906);

The Man From Scotland Yard, by David Frome (1932);

You Know Me Al, by Ring Lardner (1916);

Cleek of Scotland Yard, by T. W. Hanshew (1914);

The Queen Pedauque, by Anatole France (1892);

Scaramouche, by Rafael Sabatini (1921);

Ladies and Gentlemen, by Irvin S. Cobb (1927);

The Haunted Bookshop, by Christopher Morley (1919);

The Night of Temptation, by Victoria Cross (1912);

The Woman in Question, by John Reed Scott (1909);

Rogue Male, by Geoffrey Household (1939);

The Man in Lower Ten, by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1906);

The King's Jackal, by Richard Harding Davis (1898);

Laughing Boy, by Oliver La Farge (1929);

Portrait of Jennie, by Robert Nathan (1940);

Beau Sabreur, by P. C. Wren (1926);

The Changed Brides, by Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth (1869);

Eben Holden, by Irving Bacheller (1900);

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, by Anita Loos (1925);

Sylvia Cary, by Frances Parkinson Keyes (1919);

The Stone of Chastity, by Margery Sharp (1940);

The Adventurer, by Mika Waltari (1948);

Captain Dieppe, by Anthony Hope (1899);

Guyfford of Weare, by Jeffery Farnol (1928);

Graustark, by George Barr McCutcheon (1901);

Half a Rogue, by Harold MacGrath (1906);

Brood of the Witch Queen, by Sax Rohmer (1918);

The Green Hat, by Michael Arlen (1924);

Saturday, December 30, 2017

Thursday, December 28, 2017

A Perhaps not Forgotten AH Mystery: Point of Honour, by Madeleine E. Robins

A Perhaps not Forgotten AH Mystery: Point of Honour, by Madeleine E. Robins

a review by Rich Horton

I had planned to review a 1905 novel this week -- it's been a while since I covered a true Old Bestseller -- but the exigencies of the Christmas season intervened: Christmas itself, plus things like finally buying a new sofa, not to mention the end of the year deadlines for the Best of the Year book and for Locus. So I didn't finish the book. That leaves me an opportunity to cover a book I really liked when it came out in 2003. This review was first published at SF Site.

Madeleine Robins wrote several straight Regency novels between 1977 and 1985. She has also published a number of enjoyable stories in SF and Fantasy markets, and a couple of Fantasy novels, perhaps most notably The Stone War. Her most recent novel, from 2013, is an Historical novel, set in 13th Century Italy: Sold for Endless Rue, which looks like, from one angle, a Rapunzel retelling.

I have enjoyed many of her short stories over time, but my favorites among her work are the two Sarah Tolerance novels, Point of Honour from 2003 and Petty Treason from 2005. I only recently learned that she finally was able to publish a third: The Sleeping Partner, from the independent house Plus One, in 2011. That's good news, as I had really regretted that the series hadn't continued. These books are mysteries set in a somewhat alternate history Regency.

(I will include a link to Robins' page which itself includes links from which you can buy all the books.)

Here's my original review of the first volume:

The time is 1810. The Queen Regent is clinging to life while her children, the ineligibly married Prince of Wales and the scandalous Duke of Clarence scramble for position in the event of her death. Sarah Tolerance is a Fallen Woman -- when a teen she fell in love with her brother's fencing instructor and ran away to the Continent. But her lover has died, and she has returned to England. Her reputation is ruined, her father has repudiated her, she is an ancient 28 years old. What can she do? She is taken in by her Aunt, another Fallen Woman, who runs a very successful house of prostitution. But Sarah has no interest in being a whore, so instead she sets up as what we would call a Private Investigator, often turning up evidence for Society women of their husbands' infidelity.

The time is 1810. The Queen Regent is clinging to life while her children, the ineligibly married Prince of Wales and the scandalous Duke of Clarence scramble for position in the event of her death. Sarah Tolerance is a Fallen Woman -- when a teen she fell in love with her brother's fencing instructor and ran away to the Continent. But her lover has died, and she has returned to England. Her reputation is ruined, her father has repudiated her, she is an ancient 28 years old. What can she do? She is taken in by her Aunt, another Fallen Woman, who runs a very successful house of prostitution. But Sarah has no interest in being a whore, so instead she sets up as what we would call a Private Investigator, often turning up evidence for Society women of their husbands' infidelity.

Sarah receives a new commission from a certain Lord Trux, asking that she retrieve an Italian fan, that may be in the possession of a retired whore named Deb Cunning. Trux's unnamed boss is willing to offer quite a bit more than the fan is worth for its retrieval. Sarah's job is complicated by the fact that retired whores generally change their names, and that nobody is sure where Deb Cunning has retired to. But Sarah starts sifting through known haunts of older prostitutes, soon finding some interesting leads. However, her job is quickly complicated, as it soon seems that this fan is of considerable interest to both sides in the current political wrangle. Worse, a couple of people involved in the search turn up dead -- one is a close friend of Sarah's, the other is a woman she has visited to ask for information -- her visit timed to make her a suspect in the murder.

Sarah finally learns who her real client is -- the handsome, youngish, Earl of Versellion, who is in line to be Prime Minister if the new Regent chooses to back a Whig government. Sarah finds herself greatly attracted to Versellion, all the while exasperated by the paucity of information on the importance of the fan. This attraction deepens when she and Versellion have to go on the run in rural England, apparently under threat of murder by his Tory rivals -- or by who?

The novel nicely intertwines political intrigue, an interesting mystery about the real nature of the hidden fan (with a guessable but satisfying solution), romance, action, and a nice ending with an extra twist or two. Sarah herself is an interesting heroine, and I'm glad to know that at least two further novels are planned. [As noted above, only one more came out from the original publisher, but the third appeared in 2011.]

The SFnal elements, as mentioned, are contained in the AH nature of the setting. Many people will have immediately gathered that there was never a Queen Regent in 1810. Robins has altered English history just slightly, presumably for two reasons. One, it allows her to get away with a somewhat implausible position for her heroine: one presumes that the Queen Regent's influence, and other modest social changes, have allowed women in this 1810 just a bit more freedom (but not a whole lot!) than they had in our timeline. Two, it allows her to suggest ahistorical political intrigues as plausible, unpredictable in outcome, plot elements. (And there is a slightly more SFnal aspect to her AH: she has a minor character be part of a group of scientists who seem to be anticipating Mendelian genetics by several decades -- with a bit of actual plot relevance, even!)

Still, the main appeal is likely to mystery readers first: particularly those who enjoyed the late Kate Ross's Julian Kestrel stories, or those who enjoy Anne Perry's Victorian mysteries. Secondarily, readers of Regency romances may enjoy the book, though it does not follow standard Regency plot conventions, it does have a nice romance at its core. SF readers will like the book not as much for the relatively minor SF aspects, but for its real virtue: it's a fine historical mystery story. Or, if you will, as Robins has described it, a "hardboiled Regency".

a review by Rich Horton

I had planned to review a 1905 novel this week -- it's been a while since I covered a true Old Bestseller -- but the exigencies of the Christmas season intervened: Christmas itself, plus things like finally buying a new sofa, not to mention the end of the year deadlines for the Best of the Year book and for Locus. So I didn't finish the book. That leaves me an opportunity to cover a book I really liked when it came out in 2003. This review was first published at SF Site.

Madeleine Robins wrote several straight Regency novels between 1977 and 1985. She has also published a number of enjoyable stories in SF and Fantasy markets, and a couple of Fantasy novels, perhaps most notably The Stone War. Her most recent novel, from 2013, is an Historical novel, set in 13th Century Italy: Sold for Endless Rue, which looks like, from one angle, a Rapunzel retelling.

I have enjoyed many of her short stories over time, but my favorites among her work are the two Sarah Tolerance novels, Point of Honour from 2003 and Petty Treason from 2005. I only recently learned that she finally was able to publish a third: The Sleeping Partner, from the independent house Plus One, in 2011. That's good news, as I had really regretted that the series hadn't continued. These books are mysteries set in a somewhat alternate history Regency.

(I will include a link to Robins' page which itself includes links from which you can buy all the books.)

Here's my original review of the first volume:

The time is 1810. The Queen Regent is clinging to life while her children, the ineligibly married Prince of Wales and the scandalous Duke of Clarence scramble for position in the event of her death. Sarah Tolerance is a Fallen Woman -- when a teen she fell in love with her brother's fencing instructor and ran away to the Continent. But her lover has died, and she has returned to England. Her reputation is ruined, her father has repudiated her, she is an ancient 28 years old. What can she do? She is taken in by her Aunt, another Fallen Woman, who runs a very successful house of prostitution. But Sarah has no interest in being a whore, so instead she sets up as what we would call a Private Investigator, often turning up evidence for Society women of their husbands' infidelity.

The time is 1810. The Queen Regent is clinging to life while her children, the ineligibly married Prince of Wales and the scandalous Duke of Clarence scramble for position in the event of her death. Sarah Tolerance is a Fallen Woman -- when a teen she fell in love with her brother's fencing instructor and ran away to the Continent. But her lover has died, and she has returned to England. Her reputation is ruined, her father has repudiated her, she is an ancient 28 years old. What can she do? She is taken in by her Aunt, another Fallen Woman, who runs a very successful house of prostitution. But Sarah has no interest in being a whore, so instead she sets up as what we would call a Private Investigator, often turning up evidence for Society women of their husbands' infidelity.Sarah receives a new commission from a certain Lord Trux, asking that she retrieve an Italian fan, that may be in the possession of a retired whore named Deb Cunning. Trux's unnamed boss is willing to offer quite a bit more than the fan is worth for its retrieval. Sarah's job is complicated by the fact that retired whores generally change their names, and that nobody is sure where Deb Cunning has retired to. But Sarah starts sifting through known haunts of older prostitutes, soon finding some interesting leads. However, her job is quickly complicated, as it soon seems that this fan is of considerable interest to both sides in the current political wrangle. Worse, a couple of people involved in the search turn up dead -- one is a close friend of Sarah's, the other is a woman she has visited to ask for information -- her visit timed to make her a suspect in the murder.

Sarah finally learns who her real client is -- the handsome, youngish, Earl of Versellion, who is in line to be Prime Minister if the new Regent chooses to back a Whig government. Sarah finds herself greatly attracted to Versellion, all the while exasperated by the paucity of information on the importance of the fan. This attraction deepens when she and Versellion have to go on the run in rural England, apparently under threat of murder by his Tory rivals -- or by who?

The novel nicely intertwines political intrigue, an interesting mystery about the real nature of the hidden fan (with a guessable but satisfying solution), romance, action, and a nice ending with an extra twist or two. Sarah herself is an interesting heroine, and I'm glad to know that at least two further novels are planned. [As noted above, only one more came out from the original publisher, but the third appeared in 2011.]

The SFnal elements, as mentioned, are contained in the AH nature of the setting. Many people will have immediately gathered that there was never a Queen Regent in 1810. Robins has altered English history just slightly, presumably for two reasons. One, it allows her to get away with a somewhat implausible position for her heroine: one presumes that the Queen Regent's influence, and other modest social changes, have allowed women in this 1810 just a bit more freedom (but not a whole lot!) than they had in our timeline. Two, it allows her to suggest ahistorical political intrigues as plausible, unpredictable in outcome, plot elements. (And there is a slightly more SFnal aspect to her AH: she has a minor character be part of a group of scientists who seem to be anticipating Mendelian genetics by several decades -- with a bit of actual plot relevance, even!)

Still, the main appeal is likely to mystery readers first: particularly those who enjoyed the late Kate Ross's Julian Kestrel stories, or those who enjoy Anne Perry's Victorian mysteries. Secondarily, readers of Regency romances may enjoy the book, though it does not follow standard Regency plot conventions, it does have a nice romance at its core. SF readers will like the book not as much for the relatively minor SF aspects, but for its real virtue: it's a fine historical mystery story. Or, if you will, as Robins has described it, a "hardboiled Regency".

Thursday, December 21, 2017

Hopefully Not Forgotten Stories and a Novel by Carol Emshwiller (Report to the Men's Club and The Mount)

Hopefully Not Forgotten Stories and a Novel by Carol Emshwiller (Report to the Men's Club and The Mount)

a review by Rich Horton

I don't have a forgotten best seller or an Ace Double to write about this week (I spent the past 10 days in Mesa, AZ, on business, and the reading I did was mostly focussed on end of the year short fiction catchup). So I'm turning to a post about one of the great SF writers of her time -- and a long time it has been. I first wrote this for SF Site almost 15 years ago, in 2003.

Carol Emswhiller was born in 1921 in Ann Arbor, MI. Her father was a Professor of English and Linguistics (at, of course, the University of Michigan). She herself took degrees in Music and in Design, and was a Fulbright Fellow in France. She spent a good deal of time in France while growing up as well. She married Ed Emshwiller, the brilliant SF illustrator and experimental filmmaker, in 1949. (Many of the women featured in Ed Emshwiller's illustrations bear a certain resemblance to Carol.)

The review below is from 2003, as I've noted. Since that time she continued publishing exceptional short fiction until about 2012, and two more novels (Mister Boots in 2005 and The Secret City in 2007). I understand that she has ceased writing, due to her health (eyesight, perhaps?)

Carol Emshwiller's first SF short story was published in 1955 in Future Science Fiction. (Two earlier stories appeared in other genres: a crime fiction 'zine and a contemporary fiction magazine. (Thanks to Todd Mason for the information.)) Her early work was published mostly in Robert Lowndes's magazines (Future and Science Fiction Quarterly, as well as some crime magazines) and in F&SF. She continued to publish short fiction through the 50s and 60s, achieving at least some notice with stories like "Hunting Machine" (1957), "Pelt" (1958), "Day at the Beach" (1959), and "Chicken Icarus" (1966), each of which was chosen for a Best of the Year anthology.

Much of this early work was clever but light, as with that first story, "This Thing Called Love", a 50s social satire in the mode pioneered at H. L. Gold's Galaxy. The narrator's husband wants to emigrate to the stars, but she refuses to accompany him: why should she abandon her crushes on the robots who star in TV shows, and who could love a real human anyway? Her slightly later story, "Idol's Eye" (Future, February 1958), is perhaps more characteristic of her later work. An apparently ugly, near-blind, young farm woman is being crudely courted by a brutish neighbor, but she discovers a special "sight", that makes her the appropriate consort for a mysterious man brought by aliens.

In the mid-60s, Emshwiller's work became odder, deeper, more experimental. Many of these stories were collected in the 1974 book Joy In Our Cause, including "Sex and/or Mr. Morrison", one of the creepiest and most memorable stories in Harlan Ellison's landmark anthology Dangerous Visions. There followed two more collections, Verging on the Pertinent (1989) and The Start of the End of It All (1991), the strange feminist fantasy Carmen Dog (1988), and two novels set in the American West, Ledoyt (1995) and Leaping Man Hill (1999).

In 1999, her stories began appearing again in F&SF, and she has published a generous helping of new fiction in the past few years, in F&SF, at SCI FICTION, and in anthologies such as Leviathan Three and The Green Man. [As noted, she continued publishing short fiction in the following years through 2012, much of it in Asimov's.] And here are two new books: a story collection, and a novel, both published by Gavin Grant and Kelly Link's worthy effort, Small Beer Press.

Report to the Men's Club and Other Stories includes 19 pieces, seven of them new to this book. The reprints include seven from her recent in-genre outburst, with the other stories dating as far back as 1977. Throughout Emshwiller's lovely wry voice is evident, as are her quirky imagination, her warm regard for her characters: women, men, and other creatures, and her passionate interest in the relationship between the sexes.

Report to the Men's Club and Other Stories includes 19 pieces, seven of them new to this book. The reprints include seven from her recent in-genre outburst, with the other stories dating as far back as 1977. Throughout Emshwiller's lovely wry voice is evident, as are her quirky imagination, her warm regard for her characters: women, men, and other creatures, and her passionate interest in the relationship between the sexes.

Several of the stories reflect her interest in the Western landscape. (Emshwiller lives part of the year in a remote Western area.) Often these stories feature independent women coming to cautious accommodations with similarly independent, often mostly silent, men. The settings may or may not be the actual American West. (I have not yet read her Western novels, but I gather that this might describe these novels as well.) Thus vaguely SFnal stories like "Water Master", about the man who controls the allocation of water to a generally dry village, and the woman who becomes fascinated with him. Thus also "The Paganini of Jacob's Gulch", about a lame violinist from Scotland who moves to the American West and gets beat up for playing too well. And "Desert Child", about an old woman, an old man, and a near-feral child who end up together.

Emshwiller's range is wide, though. "Acceptance Speech" is one of the strangest and most SFnal of her recent stories, about a human kidnapped by aliens to write poetry. "Foster Mother" and "Creature" are related stories about a genetically engineered war-fighting monster who is also a child in need of love. The longest story here is "Venus Rising", originally published as a chapbook in 1992. It tells in Emshwiller's oblique, submerged, way of intelligent water creatures and their reaction to the arrival of a castaway, apparently a man, in their midst.

Other delights include "Prejudice and Pride", a striking and moving meditation on the sexual life of Elizabeth Bennett and Fitzwilliam Darcy; two stories about yetis and other mysterious creatures: "Abominable" and "Overlooking"; and "Grandma", a look at a female superhero in her old age. This is a wonderful collection of short fiction, marked by tremendous variety, a wonderful, funny, knowing, and sympathetic voice, and a truly off-center imagination.

Emshwiller's new novel is The Mount, and unlike any of her previous novels it is fairly straightforward science fiction. In simplest terms, it tells of a revolution against alien invaders. These invaders, called "Hoots", are physically weak and small, but over generations they have bred humans to serve them as "Mounts". The humans, then, become essentially pets to the aliens, treated a great deal like horses are treated by present-day humans. Thus the novel explores, quite thoughtfully, human/pet relationships, master/slave relationships, and the question of freedom versus comfort.

Emshwiller's new novel is The Mount, and unlike any of her previous novels it is fairly straightforward science fiction. In simplest terms, it tells of a revolution against alien invaders. These invaders, called "Hoots", are physically weak and small, but over generations they have bred humans to serve them as "Mounts". The humans, then, become essentially pets to the aliens, treated a great deal like horses are treated by present-day humans. Thus the novel explores, quite thoughtfully, human/pet relationships, master/slave relationships, and the question of freedom versus comfort.

There are a few different viewpoint characters, but the story is mainly told through the eye of Charley, an especially prized young Mount who is the property of the son of a very high-ranking Hoot. Charley is extremely proud, to the point of vanity, of his abilities as a Mount. And his relationship with his Hoot, who he calls "Little Master", is complex but largely loving. Loving, though, in an almost creepy Master-Slave fashion. Charley, it turns out, is the son of a rebellious human, who has gone off to live in the wilderness, and who plots to free all humans, but particularly his son. The novel's main action turns on the initial success of this scheme, and then on the ambiguous results. Charley is by no means sure that freedom is all it's cracked up to be, and moreover he misses his "Little Master". He's also jealous of his father's relationship with a woman not his mother -- his mother, of course, being basically a brood mare chosen by the Hoots.

The plot twists a couple of times from there, coming to a moving, thoughtful, and balanced resolution, if not exactly a terribly original one. The storytelling is clear and interesting. The age of the protagonist, the theme, and the relatively simple storytelling make this novel, I would think, appealing to younger readers, but it certainly will satisfy adults as well.

Carol Emshwiller is a real treasure. She still seems underappreciated to me, but this late burst of productivity may help remedy that situation. Both The Mount and Report to the Men's Club are first rate books. I think I'd choose the story collection as the better book, for its range, complexity, and wit. But either way, I'm thrilled to see these books, and I look forward to many more stories from this writer. [And, as noted, we got many more stories, and two more novels, through 2012.]

a review by Rich Horton

I don't have a forgotten best seller or an Ace Double to write about this week (I spent the past 10 days in Mesa, AZ, on business, and the reading I did was mostly focussed on end of the year short fiction catchup). So I'm turning to a post about one of the great SF writers of her time -- and a long time it has been. I first wrote this for SF Site almost 15 years ago, in 2003.

Carol Emswhiller was born in 1921 in Ann Arbor, MI. Her father was a Professor of English and Linguistics (at, of course, the University of Michigan). She herself took degrees in Music and in Design, and was a Fulbright Fellow in France. She spent a good deal of time in France while growing up as well. She married Ed Emshwiller, the brilliant SF illustrator and experimental filmmaker, in 1949. (Many of the women featured in Ed Emshwiller's illustrations bear a certain resemblance to Carol.)

The review below is from 2003, as I've noted. Since that time she continued publishing exceptional short fiction until about 2012, and two more novels (Mister Boots in 2005 and The Secret City in 2007). I understand that she has ceased writing, due to her health (eyesight, perhaps?)

Carol Emshwiller's first SF short story was published in 1955 in Future Science Fiction. (Two earlier stories appeared in other genres: a crime fiction 'zine and a contemporary fiction magazine. (Thanks to Todd Mason for the information.)) Her early work was published mostly in Robert Lowndes's magazines (Future and Science Fiction Quarterly, as well as some crime magazines) and in F&SF. She continued to publish short fiction through the 50s and 60s, achieving at least some notice with stories like "Hunting Machine" (1957), "Pelt" (1958), "Day at the Beach" (1959), and "Chicken Icarus" (1966), each of which was chosen for a Best of the Year anthology.

Much of this early work was clever but light, as with that first story, "This Thing Called Love", a 50s social satire in the mode pioneered at H. L. Gold's Galaxy. The narrator's husband wants to emigrate to the stars, but she refuses to accompany him: why should she abandon her crushes on the robots who star in TV shows, and who could love a real human anyway? Her slightly later story, "Idol's Eye" (Future, February 1958), is perhaps more characteristic of her later work. An apparently ugly, near-blind, young farm woman is being crudely courted by a brutish neighbor, but she discovers a special "sight", that makes her the appropriate consort for a mysterious man brought by aliens.

In the mid-60s, Emshwiller's work became odder, deeper, more experimental. Many of these stories were collected in the 1974 book Joy In Our Cause, including "Sex and/or Mr. Morrison", one of the creepiest and most memorable stories in Harlan Ellison's landmark anthology Dangerous Visions. There followed two more collections, Verging on the Pertinent (1989) and The Start of the End of It All (1991), the strange feminist fantasy Carmen Dog (1988), and two novels set in the American West, Ledoyt (1995) and Leaping Man Hill (1999).

In 1999, her stories began appearing again in F&SF, and she has published a generous helping of new fiction in the past few years, in F&SF, at SCI FICTION, and in anthologies such as Leviathan Three and The Green Man. [As noted, she continued publishing short fiction in the following years through 2012, much of it in Asimov's.] And here are two new books: a story collection, and a novel, both published by Gavin Grant and Kelly Link's worthy effort, Small Beer Press.

Report to the Men's Club and Other Stories includes 19 pieces, seven of them new to this book. The reprints include seven from her recent in-genre outburst, with the other stories dating as far back as 1977. Throughout Emshwiller's lovely wry voice is evident, as are her quirky imagination, her warm regard for her characters: women, men, and other creatures, and her passionate interest in the relationship between the sexes.

Report to the Men's Club and Other Stories includes 19 pieces, seven of them new to this book. The reprints include seven from her recent in-genre outburst, with the other stories dating as far back as 1977. Throughout Emshwiller's lovely wry voice is evident, as are her quirky imagination, her warm regard for her characters: women, men, and other creatures, and her passionate interest in the relationship between the sexes.Several of the stories reflect her interest in the Western landscape. (Emshwiller lives part of the year in a remote Western area.) Often these stories feature independent women coming to cautious accommodations with similarly independent, often mostly silent, men. The settings may or may not be the actual American West. (I have not yet read her Western novels, but I gather that this might describe these novels as well.) Thus vaguely SFnal stories like "Water Master", about the man who controls the allocation of water to a generally dry village, and the woman who becomes fascinated with him. Thus also "The Paganini of Jacob's Gulch", about a lame violinist from Scotland who moves to the American West and gets beat up for playing too well. And "Desert Child", about an old woman, an old man, and a near-feral child who end up together.

Emshwiller's range is wide, though. "Acceptance Speech" is one of the strangest and most SFnal of her recent stories, about a human kidnapped by aliens to write poetry. "Foster Mother" and "Creature" are related stories about a genetically engineered war-fighting monster who is also a child in need of love. The longest story here is "Venus Rising", originally published as a chapbook in 1992. It tells in Emshwiller's oblique, submerged, way of intelligent water creatures and their reaction to the arrival of a castaway, apparently a man, in their midst.

Other delights include "Prejudice and Pride", a striking and moving meditation on the sexual life of Elizabeth Bennett and Fitzwilliam Darcy; two stories about yetis and other mysterious creatures: "Abominable" and "Overlooking"; and "Grandma", a look at a female superhero in her old age. This is a wonderful collection of short fiction, marked by tremendous variety, a wonderful, funny, knowing, and sympathetic voice, and a truly off-center imagination.

Emshwiller's new novel is The Mount, and unlike any of her previous novels it is fairly straightforward science fiction. In simplest terms, it tells of a revolution against alien invaders. These invaders, called "Hoots", are physically weak and small, but over generations they have bred humans to serve them as "Mounts". The humans, then, become essentially pets to the aliens, treated a great deal like horses are treated by present-day humans. Thus the novel explores, quite thoughtfully, human/pet relationships, master/slave relationships, and the question of freedom versus comfort.

Emshwiller's new novel is The Mount, and unlike any of her previous novels it is fairly straightforward science fiction. In simplest terms, it tells of a revolution against alien invaders. These invaders, called "Hoots", are physically weak and small, but over generations they have bred humans to serve them as "Mounts". The humans, then, become essentially pets to the aliens, treated a great deal like horses are treated by present-day humans. Thus the novel explores, quite thoughtfully, human/pet relationships, master/slave relationships, and the question of freedom versus comfort.There are a few different viewpoint characters, but the story is mainly told through the eye of Charley, an especially prized young Mount who is the property of the son of a very high-ranking Hoot. Charley is extremely proud, to the point of vanity, of his abilities as a Mount. And his relationship with his Hoot, who he calls "Little Master", is complex but largely loving. Loving, though, in an almost creepy Master-Slave fashion. Charley, it turns out, is the son of a rebellious human, who has gone off to live in the wilderness, and who plots to free all humans, but particularly his son. The novel's main action turns on the initial success of this scheme, and then on the ambiguous results. Charley is by no means sure that freedom is all it's cracked up to be, and moreover he misses his "Little Master". He's also jealous of his father's relationship with a woman not his mother -- his mother, of course, being basically a brood mare chosen by the Hoots.

The plot twists a couple of times from there, coming to a moving, thoughtful, and balanced resolution, if not exactly a terribly original one. The storytelling is clear and interesting. The age of the protagonist, the theme, and the relatively simple storytelling make this novel, I would think, appealing to younger readers, but it certainly will satisfy adults as well.

Carol Emshwiller is a real treasure. She still seems underappreciated to me, but this late burst of productivity may help remedy that situation. Both The Mount and Report to the Men's Club are first rate books. I think I'd choose the story collection as the better book, for its range, complexity, and wit. But either way, I'm thrilled to see these books, and I look forward to many more stories from this writer. [And, as noted, we got many more stories, and two more novels, through 2012.]

Thursday, December 14, 2017

A Recent Crime Novel: Texas Vigilante, by Bill Crider

A Recent Crime Novel: Texas Vigilante, by Bill Crider

A Recent Crime Novel: Texas Vigilante, by Bill Cridera review by Rich Horton

Bill Crider (b. 1941) is best known to me as a serious book collector with great knowledge in genres close to me -- pulps and mystery primarily, but also some interest in SF and Fantasy. He was a long time English professor. He is a life-long Texan. And he also has written a great many novels, mostly in the mystery/crime genre. He has won two Anthony awards, and been nominated for several Edgars, for his mystery fiction.

I had known Bill on a mailing list for some years, but I met him first just a few weeks ago at the World Fantasy Convention in San Antonio (not far from where Bill was born). We spoke only briefly. And just recently I heard that Bill has gone into hospice. It was clearly time for me to remedy a longstanding lacuna in my reading, and get to one of his books. (Bill was also a regular contributor to Patti Abbott's Friday's Forgotten Books.)

I chose Texas Vigilante, the second of his novels about Ellie Taine. Both books were published by Dell in 1999. The first of these is Outrage at Blanco, in which, I deduce from Texas Vigilante, Ellie is raped, and her husband murdered, after which she chases down the perpetrators and kills a couple of them. Texas Vigilante is set a year or so later. (Some time in the past, it seems, based on the lack of automobiles, which makes the ebook cover picture to the right not very accurate.) Ellie has inherited a ranch in Blanco, TX, from her friend Jonathan Crossland, and she is running it with the help of Lane Tolbert, his wife Sue and their young daughter Laurie. Meantime, Sue's brother, Angel Ware, is in prison. He's guilty of a whole raft of crimes (including burning down his parents' house with them in it) -- he's a pure sociopath. The prison guard is a sociopath himself, fond of torturing Angel for no apparent reason, and one day Angel takes the opportunity to escape while on a work detail. He is accompanied by another sociopath, the teenaged Hoot Riley (who seems a bit too interested in girls even younger then he is), as well as a professional criminal (Abilene Jack Sturdivant) and an unfortunate loser (Ben Jephson). Angel is the brains of the outfit, so they stick with him, even as his obsession to find his sister and her family seems dangerous.

Lane's brother Brady is a Texas Ranger, the one who actually arrested Angel, though Sue had turned him in. Obviously, Angel wants revenge on Sue and on Brady. The story then follows Angel's path to finding Sue; Brady's attempts to track down the escapees, and Ellie and her fellow ranchers as they worry about the danger posed by Angel. There are a variety of viewpoint characters, noticeably including a couple of less influential figures: Ben Jephson, the hapless prisoner dragged along on Angel's quest; and Shag Tillman, a lazy and cowardly but generally good-hearted Sheriff at Blanco.

The story is crisply told and fast-moving. There is a fair amount of mordant humor; and a lot of glimpses on the mental processes of some evil people, as well as some good people. Angel's plan is to kidnap Laurie -- who actually seems to like Angel, and seems to be one of the few people Angel has any concern for. That goes smoothly enough, followed by an obvious attempt to lure Brady and Lane Tolbert into an ambush. He doesn't count on Ellie Taine, however ... Nor, perhaps, on the unreliability of his fellow criminals. Nor on the Texas rain.

The book delivers on what it promised -- lots of action (and violence), lots of tension, really bad guys and competent good guys. It's a fun read (for values of fun that included spending a lot of time with some nasty people). It is, as I mentioned, the second book about Ellie Taine -- as far as I can tell, however, it was also the last, which is a shame. It seems at least one more book was potentially in the offing -- though the thought of another horrifying crime perpetrated against those close to her is a bit hard to take!

It's a shame we won't have Bill Crider -- and his writing and his knowledge -- for much longer, but I am glad I had the chance to meet him once, and to know him online for longer.

Thursday, December 7, 2017

Old Bestseller: The Auction Block, by Rex Beach

Old Bestseller: The Auction Block, by Rex Beach

a review by Rich Horton

It's been a while since I published a review of an Old Bestseller of the sort that I feel is the core mission of this blog: forgotten popular fiction from the first half of the 20th Century. But here's a very good example of that sort of thing. And it's published on an auspicious day! (No, not Pearl Harbor Day. Instead, the 68th anniversary of the author's death!)

Rex Beach (1877-1949) was born in Michigan, raised in Florida, and went to law school in Chicago. He prospected for gold in Alaska (unsuccessfully), and he won a silver medal as part of the US Water Polo team in the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis. He turned to writing about this time, and his second novel, The Spoilers (1906) was the 8th bestselling novel of that year (according to Publishers' Weekly). He had the second, third and eighth bestselling novels of 1908. 1909, and 1912 as well. The Spoilers (based on his experiences in Alaska, and on a true incident of corruption) was made into a movie at least 5 times, once starring Gary Cooper, another time John Wayne.

Beach's novels were generally adventure novels, of the "he man" school of literature, often set on the frontier. In this context, The Auction Block (1914) is an outlier: it is to an extent (if not all that successfully) a "social" novel, it is set in New York society (and the demimonde), it is a love story, and it features relatively little action (though there is some gunplay, fast cars, and fights, just not a whole lot).

My copy appears to be the First Edition, from Harper and Brothers (in fair condition, no dj). It is copiously, and quite nicely, illustrated by the famous illustrator Charles Dana Gibson (of the "Gibson Girl").

It opens with the Knight family, from Upstate New York, in some trouble. Their father, Peter, a very weak man, had lost his bid for re-election as Sheriff, due to his corrupt actions. The son, Jim, is lazy and morally degenerate. They are to move to New York City, where a political mentor of Mr. Knight has found him a patronage job. But, led by Mrs. Knight and Jim, they hatch a plan for greater riches, unbeknownst (mostly) to the daughter, Lorelei, who is beautiful and innocent and morally upstanding. This plan is to have Lorelei go on the musical stage and lure a rich man into marriage.

Lorelei agrees to the stage part of things, to help support the family, which becomes particularly important after Peter has an accident and loses his job. Lorelei is quite a hit from the start, because of her beauty, though she is a mediocre singer and actress. She soon learns that a big part of the job is to "entertain" the rich men who come to see her. She maintains her moral standards to a degree: she eats with the men and goes to parties, but doesn't drink, nor does she allow the men further liberties (though that would be more lucrative).

She impresses a cynical critic, Campbell Pope, with her freshness, and she becomes a friend to a dyspeptic middle-aged banker, Mr. Merkle, who gives her plenty of advice about steering away from the worst elements of her milieu. Her dressing room mate is Lilas Lynn, a somewhat coarser character who has become the mistress of a married steel magnate, Jarvis Hammon. Lorelei also makes a surprising friend: the notorious Adoree Demorest, regarded as the wickedest actress on Broadway. About this time, Bob Wharton, the dissipated son of another steel man, Hannibal Wharton of Pittsburg (as it seemed to be spelled often those days), falls head over heels for Lorelei, but she rejects his advances.

She impresses a cynical critic, Campbell Pope, with her freshness, and she becomes a friend to a dyspeptic middle-aged banker, Mr. Merkle, who gives her plenty of advice about steering away from the worst elements of her milieu. Her dressing room mate is Lilas Lynn, a somewhat coarser character who has become the mistress of a married steel magnate, Jarvis Hammon. Lorelei also makes a surprising friend: the notorious Adoree Demorest, regarded as the wickedest actress on Broadway. About this time, Bob Wharton, the dissipated son of another steel man, Hannibal Wharton of Pittsburg (as it seemed to be spelled often those days), falls head over heels for Lorelei, but she rejects his advances.

Lilas has plans to to trap Hammon into marriage. (Part of her motivation is revenge: she is the daughter of a steelworker who died in an accident in one of Hammon's plants.) To do so she needs to cause a scandal, and unfortunately her machinations enmesh Lorelei and Mr. Merkle, who are together only because he was rescuing her from Bob Wharton's importunings. Jim Knight, now a small time gangster, is involved as well. Before long Lilas's plans are coming to fruition; and in addition, Lorelei's nasty family is trying to blackmail Mr. Merkle. But Jarvis Hammon and Lilas Lynn have a shocking falling out, which leads to Lilas killing Hammon (in self-defense, to be fair), and Bob Wharton and Mr. Merkle help the dying Hammon hush up the scandalous aspects.

Desperate for money, the Knights scheme to trick Bob Wharton into asking Lorelei to marry him. She is completely against this, but her vile brother tricks her into an ambiguous situation, and Lorelei, not feeling well anyway after witnessing Hammon's murder, against her better instincts accepts a drunken proposal from Bob.

The marriage (due to brother Jim's plotting) happens immediately, and the Knights begin to work on Hannibal Wharton for a payoff in exchange for a divorce. But Lorelei will have none of it. She tells Bob that he can have the divorce no strings attached -- but he begs her to stick with him: he truly believes he loves her. She agrees on one condition: that he quit drinking.

The rest of the novel concerns Bob's fitful efforts at reform, with plenty of backsliding. He is pushed to get a job, and after his father (who has cut him off without a penny) blacklists him from any job with his associates, Bob has to come up with something on his own. He has surprising success, but every step forward is the occasion for a disastrous step backward, usually due to falling spectacularly off the wagon. Things come to a terrible head when they attend a country house party, and Lorelei is disgusted by the immorality of the "Society" folks on hand, especially when one man attempts to rape her. She is ready to break off with Bob completely (he was drunk and thus unable to protect Lorelei), but then she learns she is pregnant.

It's easy to see the resolution: the child helps Bob to truly face his responsibilities, and also eventually melts the hearts of Bob's parents. There is still the Knight family to deal with: they are still trying to extort money from Hannibal Wharton. And there is another crisis when Lilas Lynn, now a desperate cocaine addict, returns and tries to cause more chaos. Not to mention Jim Knight's mob connections ... But there are plenty of dei ex machinae to go around and solve all these problems. And there's a sweet if silly subplot involving Adoree Demorest and the cynical critic Campbell Pope.

It's really not a very good novel. Its attempts at social relevance: dealing with the problems of steelworkers, police corruption and mob violence, drug addiction, alcoholism, and the abuse of the showgirls working on Broadway, are decidedly clumsy if somewhat well-meant. It has all too typical racist bits, and especially anti-Semitic aspects (Lilas Lynn, the villainess, is Jewish, and described in quite absurd terms). The working out of the plot is terribly convenient.

And for all that, I kind of enjoyed it, and was even rather moved at the conclusion. As with so many of these Old Bestsellers, it's really not a mystery that it sold well -- even though I really see no great reason for a revival.

a review by Rich Horton

It's been a while since I published a review of an Old Bestseller of the sort that I feel is the core mission of this blog: forgotten popular fiction from the first half of the 20th Century. But here's a very good example of that sort of thing. And it's published on an auspicious day! (No, not Pearl Harbor Day. Instead, the 68th anniversary of the author's death!)

Rex Beach (1877-1949) was born in Michigan, raised in Florida, and went to law school in Chicago. He prospected for gold in Alaska (unsuccessfully), and he won a silver medal as part of the US Water Polo team in the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis. He turned to writing about this time, and his second novel, The Spoilers (1906) was the 8th bestselling novel of that year (according to Publishers' Weekly). He had the second, third and eighth bestselling novels of 1908. 1909, and 1912 as well. The Spoilers (based on his experiences in Alaska, and on a true incident of corruption) was made into a movie at least 5 times, once starring Gary Cooper, another time John Wayne.

Beach's novels were generally adventure novels, of the "he man" school of literature, often set on the frontier. In this context, The Auction Block (1914) is an outlier: it is to an extent (if not all that successfully) a "social" novel, it is set in New York society (and the demimonde), it is a love story, and it features relatively little action (though there is some gunplay, fast cars, and fights, just not a whole lot).

My copy appears to be the First Edition, from Harper and Brothers (in fair condition, no dj). It is copiously, and quite nicely, illustrated by the famous illustrator Charles Dana Gibson (of the "Gibson Girl").

It opens with the Knight family, from Upstate New York, in some trouble. Their father, Peter, a very weak man, had lost his bid for re-election as Sheriff, due to his corrupt actions. The son, Jim, is lazy and morally degenerate. They are to move to New York City, where a political mentor of Mr. Knight has found him a patronage job. But, led by Mrs. Knight and Jim, they hatch a plan for greater riches, unbeknownst (mostly) to the daughter, Lorelei, who is beautiful and innocent and morally upstanding. This plan is to have Lorelei go on the musical stage and lure a rich man into marriage.

Lorelei agrees to the stage part of things, to help support the family, which becomes particularly important after Peter has an accident and loses his job. Lorelei is quite a hit from the start, because of her beauty, though she is a mediocre singer and actress. She soon learns that a big part of the job is to "entertain" the rich men who come to see her. She maintains her moral standards to a degree: she eats with the men and goes to parties, but doesn't drink, nor does she allow the men further liberties (though that would be more lucrative).

She impresses a cynical critic, Campbell Pope, with her freshness, and she becomes a friend to a dyspeptic middle-aged banker, Mr. Merkle, who gives her plenty of advice about steering away from the worst elements of her milieu. Her dressing room mate is Lilas Lynn, a somewhat coarser character who has become the mistress of a married steel magnate, Jarvis Hammon. Lorelei also makes a surprising friend: the notorious Adoree Demorest, regarded as the wickedest actress on Broadway. About this time, Bob Wharton, the dissipated son of another steel man, Hannibal Wharton of Pittsburg (as it seemed to be spelled often those days), falls head over heels for Lorelei, but she rejects his advances.

She impresses a cynical critic, Campbell Pope, with her freshness, and she becomes a friend to a dyspeptic middle-aged banker, Mr. Merkle, who gives her plenty of advice about steering away from the worst elements of her milieu. Her dressing room mate is Lilas Lynn, a somewhat coarser character who has become the mistress of a married steel magnate, Jarvis Hammon. Lorelei also makes a surprising friend: the notorious Adoree Demorest, regarded as the wickedest actress on Broadway. About this time, Bob Wharton, the dissipated son of another steel man, Hannibal Wharton of Pittsburg (as it seemed to be spelled often those days), falls head over heels for Lorelei, but she rejects his advances.Lilas has plans to to trap Hammon into marriage. (Part of her motivation is revenge: she is the daughter of a steelworker who died in an accident in one of Hammon's plants.) To do so she needs to cause a scandal, and unfortunately her machinations enmesh Lorelei and Mr. Merkle, who are together only because he was rescuing her from Bob Wharton's importunings. Jim Knight, now a small time gangster, is involved as well. Before long Lilas's plans are coming to fruition; and in addition, Lorelei's nasty family is trying to blackmail Mr. Merkle. But Jarvis Hammon and Lilas Lynn have a shocking falling out, which leads to Lilas killing Hammon (in self-defense, to be fair), and Bob Wharton and Mr. Merkle help the dying Hammon hush up the scandalous aspects.

Desperate for money, the Knights scheme to trick Bob Wharton into asking Lorelei to marry him. She is completely against this, but her vile brother tricks her into an ambiguous situation, and Lorelei, not feeling well anyway after witnessing Hammon's murder, against her better instincts accepts a drunken proposal from Bob.

The marriage (due to brother Jim's plotting) happens immediately, and the Knights begin to work on Hannibal Wharton for a payoff in exchange for a divorce. But Lorelei will have none of it. She tells Bob that he can have the divorce no strings attached -- but he begs her to stick with him: he truly believes he loves her. She agrees on one condition: that he quit drinking.

The rest of the novel concerns Bob's fitful efforts at reform, with plenty of backsliding. He is pushed to get a job, and after his father (who has cut him off without a penny) blacklists him from any job with his associates, Bob has to come up with something on his own. He has surprising success, but every step forward is the occasion for a disastrous step backward, usually due to falling spectacularly off the wagon. Things come to a terrible head when they attend a country house party, and Lorelei is disgusted by the immorality of the "Society" folks on hand, especially when one man attempts to rape her. She is ready to break off with Bob completely (he was drunk and thus unable to protect Lorelei), but then she learns she is pregnant.

It's easy to see the resolution: the child helps Bob to truly face his responsibilities, and also eventually melts the hearts of Bob's parents. There is still the Knight family to deal with: they are still trying to extort money from Hannibal Wharton. And there is another crisis when Lilas Lynn, now a desperate cocaine addict, returns and tries to cause more chaos. Not to mention Jim Knight's mob connections ... But there are plenty of dei ex machinae to go around and solve all these problems. And there's a sweet if silly subplot involving Adoree Demorest and the cynical critic Campbell Pope.

It's really not a very good novel. Its attempts at social relevance: dealing with the problems of steelworkers, police corruption and mob violence, drug addiction, alcoholism, and the abuse of the showgirls working on Broadway, are decidedly clumsy if somewhat well-meant. It has all too typical racist bits, and especially anti-Semitic aspects (Lilas Lynn, the villainess, is Jewish, and described in quite absurd terms). The working out of the plot is terribly convenient.

And for all that, I kind of enjoyed it, and was even rather moved at the conclusion. As with so many of these Old Bestsellers, it's really not a mystery that it sold well -- even though I really see no great reason for a revival.

Monday, December 4, 2017

World Fantasy Convention, 2017, Part V: Day 4

World Fantasy Convention, 2017, Part V: Day 4

Last day. I'll begin with some mentions of people I talked to earlier, whom I had forgotten when doing previous writeups. I talked to Michael Damian Thomas for some time -- about his and Lynne's recent move to Champaign (where I went to college), and (with Sarah Pinsker, as previously mentioned) about music -- Tom Petty, and other concerts we've attended, and other people who are, well, getting on a bit (as are we all). Of course I've known Michael for years and years. I also had a good talk with Tegan Moore, who had a really good story in Asimov's last year ("Epitome"). She mentioned some frustration with selling her recent work, which sounds pretty ambitious -- I think she'll make it, and pretty impressively, before long.

I also had a good talk with Brad Denton, and Caroline Spector, and I managed to put in a request for a song at "Roomcon", the traditional room party at ConQuesT where Brad (as "Blind Lemon") and Caroline play excellent music. (The request was for another song about a Texas city: Robert Earl Keen's great "Corpus Christi Bay".) Others I met (some quite briefly) included Robert V. S. Redick, Jenn Reese, Caroline Yoachim, Rajan Khanna, Greg van Eekhout, Gary Wolfe, and doubtless several more I'm embarrassed to have forgotten.

Sunday morning I came downstairs and ran into (not literally) Charlie Finlay, along with three of his F&SF writers: Austin Habershaw, G. V. (for Gemma, I think) Anderson, and Nebula winner William Ledbetter. Ledbetter's Nebula was for a story in F&SF last year, and I was impressed with stories by Anderson and Habershaw in the same quite recent issue. Indeed, Anderson went on to take the World Fantasy Award for Best Short Story later that day. I had forgotten that story, perhaps because the title is in German: "Das Steingeschöpf", but I looked it up again (it was in Strange Horizons late last year, and I first read it on a morning walk when I was in Southern California for work about a year ago), and it's pretty impressive. We talked about things like the San Antonio climate and baseball.

We skipped breakfast (grabbed a snack in the Con suite), and there were panels at 10 and 11 I wanted to see. The first was on Pulp Era Influences: The Expiration Date. Panelists were James Stoddard, Gary K. Wolfe, Betsy Mitchell, and Jeffrey Shanks. Most agreed that lots of Pulp Era writers remain influential, and they mentioned as well some contemporary work explicitly in the "Pulp" mode. Betsy mentioned her ebook project, Open Road, which brings a lot of out of print work back at least electronically.

The second panel was on the Best Fantasy Novels of 2017. Willie Siros, Liza Groen Trombi, Jim Minz, and Joe Monti were the panelists. I always find these worthwhile, and there was a good discussion. I also had a good talk with Joe after the panel.

Finally, we attended Karen Joy Fowler's reading, from her upcoming novel about the John Wilkes Booth family. It was very intriguing. I did get a chance to introduce Mary Ann to Karen a bit later -- as I've mentioned before, Mary Ann doesn't read much SF, but she does read Karen Joy Fowler.

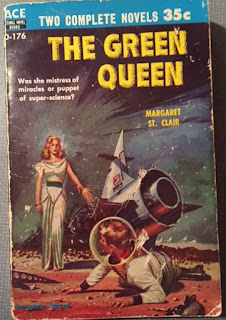

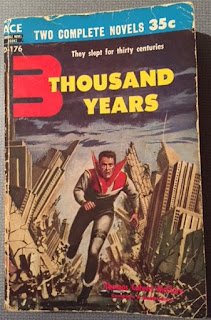

I took one more swing through the dealers' room, but didn't buy anything more. I was quite restrained this Con as far as buying books: the Crowley chapbook ("An Earthly Mother Sits and Sing"), Kij Johnson's The River Bank, Walter Jon Williams' Quillifer, a couple of old magazines, one Ace Double; and a couple of books given to me (Threshold of Eternity by Brunner and Broderick, and Tales from a Talking Board, featuring a Joe McDermott story).

So we headed out. One goal was to eat at Schlotzky's, long a favorite sandwich place of ours. Alas, the St. Louis franchises all closed over a decade ago. We've been to one in Seneca, SC (near Clemson) a few times, and to one in Joplin, MO, a few times, but we had noted that Texas, including San Antonio, has Schlotzky's, so we stopped at one on the way out of town. The sandwiches were a bit disappointing: sloppily prepared, and they were out of onions. Hey, I know there's great food in Texas (and we had some pretty good food!), but we had some disappointments too.

While at Schlotzky's, we saw on TV the news about the shootings at the church in Sutherland Springs, only about 40 miles away from the restaurant. I'll avoid any overtly political statements in this forum, however.

We headed up to Dallas, this time saving 20 minutes is Austin by taking a huge loop around the city. We also avoided a long delay in Waco thanks to our GPS guiding us off the highway to the frontage road to miss an accident-caused backup. We got to Dallas early enough to go out for pizza with Paul and Diane and the twins, David and Christopher. I can't remember the name of the pizza place -- the food was good but the service was incredibly slow. (The people at the table next to us made a bit of a scene about that.)

In the morning, first we had another of Diane's spectacular breakfasts. We decided we had time for one antique mall, and we (more or less randomly) picked one in Sherman, TX. It was a fine place, and I found a copy of Black Alice, by Thom Demijohn (Thomas Disch and John Sladek). Alas, a Book Club edition -- apparently the true first is pretty rare. We took the more normal way home, through Oklahoma to I-44, then into Missouri. We stopped in Joplin at Schlotzky's again -- it was better than the San Antonio one.

We had been playing various different Pandora stations along the way, some of mine and some of Mary Ann's, and we ended, for most of the way across Missouri, by playing a station I have intended to focus on show tunes -- based on my fondness for big cheesy tunes like "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina" and "I Dreamed a Dream", not to mention lots of Sondheim. Mary Ann tried to prove that the phone listens to us by asking for songs from the likes of My Fair Lady -- and sure enough, not long after, "I Could Have Danced All Night" popped up -- the for Disney song, which took a while longer but eventually the phone got the hint and played something from The Little Mermaid.

We got in latish but not too late. I have to say, World Fantasy Convention lived up to what many people have told me -- that's it's a favorite convention of a whole bunch of people, for its literary and professional focus, and its relatively small size. I had a really wonderful time. As ever, the key to any Con is the people you meet -- old friends and new -- the conversations. I'll be back again as soon as I can swing it. (Alas, Baltimore next year might be hard, given we already have plans to go to San Jose for Worldcon, and to Montreal for Jo Walton's Scintillation.)

Finally, I need to mention the World Fantasy Award winners. We missed the award presentation, but here are the nominees and winners. Congratulations to them all, and I am particularly happy with Kij Johnson's award for the utterly magnificent Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe. And I should also add special congratulations to Neile Graham, another old friend from the much-missed Golden Age of the SFF.Net newsgroups. I did have a chance to finally meet Neile in the flesh, and talk with her for a bit.

Here are links to all five installments of this con report:

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Last day. I'll begin with some mentions of people I talked to earlier, whom I had forgotten when doing previous writeups. I talked to Michael Damian Thomas for some time -- about his and Lynne's recent move to Champaign (where I went to college), and (with Sarah Pinsker, as previously mentioned) about music -- Tom Petty, and other concerts we've attended, and other people who are, well, getting on a bit (as are we all). Of course I've known Michael for years and years. I also had a good talk with Tegan Moore, who had a really good story in Asimov's last year ("Epitome"). She mentioned some frustration with selling her recent work, which sounds pretty ambitious -- I think she'll make it, and pretty impressively, before long.

I also had a good talk with Brad Denton, and Caroline Spector, and I managed to put in a request for a song at "Roomcon", the traditional room party at ConQuesT where Brad (as "Blind Lemon") and Caroline play excellent music. (The request was for another song about a Texas city: Robert Earl Keen's great "Corpus Christi Bay".) Others I met (some quite briefly) included Robert V. S. Redick, Jenn Reese, Caroline Yoachim, Rajan Khanna, Greg van Eekhout, Gary Wolfe, and doubtless several more I'm embarrassed to have forgotten.

Sunday morning I came downstairs and ran into (not literally) Charlie Finlay, along with three of his F&SF writers: Austin Habershaw, G. V. (for Gemma, I think) Anderson, and Nebula winner William Ledbetter. Ledbetter's Nebula was for a story in F&SF last year, and I was impressed with stories by Anderson and Habershaw in the same quite recent issue. Indeed, Anderson went on to take the World Fantasy Award for Best Short Story later that day. I had forgotten that story, perhaps because the title is in German: "Das Steingeschöpf", but I looked it up again (it was in Strange Horizons late last year, and I first read it on a morning walk when I was in Southern California for work about a year ago), and it's pretty impressive. We talked about things like the San Antonio climate and baseball.

We skipped breakfast (grabbed a snack in the Con suite), and there were panels at 10 and 11 I wanted to see. The first was on Pulp Era Influences: The Expiration Date. Panelists were James Stoddard, Gary K. Wolfe, Betsy Mitchell, and Jeffrey Shanks. Most agreed that lots of Pulp Era writers remain influential, and they mentioned as well some contemporary work explicitly in the "Pulp" mode. Betsy mentioned her ebook project, Open Road, which brings a lot of out of print work back at least electronically.

The second panel was on the Best Fantasy Novels of 2017. Willie Siros, Liza Groen Trombi, Jim Minz, and Joe Monti were the panelists. I always find these worthwhile, and there was a good discussion. I also had a good talk with Joe after the panel.

Finally, we attended Karen Joy Fowler's reading, from her upcoming novel about the John Wilkes Booth family. It was very intriguing. I did get a chance to introduce Mary Ann to Karen a bit later -- as I've mentioned before, Mary Ann doesn't read much SF, but she does read Karen Joy Fowler.

I took one more swing through the dealers' room, but didn't buy anything more. I was quite restrained this Con as far as buying books: the Crowley chapbook ("An Earthly Mother Sits and Sing"), Kij Johnson's The River Bank, Walter Jon Williams' Quillifer, a couple of old magazines, one Ace Double; and a couple of books given to me (Threshold of Eternity by Brunner and Broderick, and Tales from a Talking Board, featuring a Joe McDermott story).

So we headed out. One goal was to eat at Schlotzky's, long a favorite sandwich place of ours. Alas, the St. Louis franchises all closed over a decade ago. We've been to one in Seneca, SC (near Clemson) a few times, and to one in Joplin, MO, a few times, but we had noted that Texas, including San Antonio, has Schlotzky's, so we stopped at one on the way out of town. The sandwiches were a bit disappointing: sloppily prepared, and they were out of onions. Hey, I know there's great food in Texas (and we had some pretty good food!), but we had some disappointments too.

While at Schlotzky's, we saw on TV the news about the shootings at the church in Sutherland Springs, only about 40 miles away from the restaurant. I'll avoid any overtly political statements in this forum, however.

We headed up to Dallas, this time saving 20 minutes is Austin by taking a huge loop around the city. We also avoided a long delay in Waco thanks to our GPS guiding us off the highway to the frontage road to miss an accident-caused backup. We got to Dallas early enough to go out for pizza with Paul and Diane and the twins, David and Christopher. I can't remember the name of the pizza place -- the food was good but the service was incredibly slow. (The people at the table next to us made a bit of a scene about that.)

In the morning, first we had another of Diane's spectacular breakfasts. We decided we had time for one antique mall, and we (more or less randomly) picked one in Sherman, TX. It was a fine place, and I found a copy of Black Alice, by Thom Demijohn (Thomas Disch and John Sladek). Alas, a Book Club edition -- apparently the true first is pretty rare. We took the more normal way home, through Oklahoma to I-44, then into Missouri. We stopped in Joplin at Schlotzky's again -- it was better than the San Antonio one.

We had been playing various different Pandora stations along the way, some of mine and some of Mary Ann's, and we ended, for most of the way across Missouri, by playing a station I have intended to focus on show tunes -- based on my fondness for big cheesy tunes like "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina" and "I Dreamed a Dream", not to mention lots of Sondheim. Mary Ann tried to prove that the phone listens to us by asking for songs from the likes of My Fair Lady -- and sure enough, not long after, "I Could Have Danced All Night" popped up -- the for Disney song, which took a while longer but eventually the phone got the hint and played something from The Little Mermaid.

We got in latish but not too late. I have to say, World Fantasy Convention lived up to what many people have told me -- that's it's a favorite convention of a whole bunch of people, for its literary and professional focus, and its relatively small size. I had a really wonderful time. As ever, the key to any Con is the people you meet -- old friends and new -- the conversations. I'll be back again as soon as I can swing it. (Alas, Baltimore next year might be hard, given we already have plans to go to San Jose for Worldcon, and to Montreal for Jo Walton's Scintillation.)

Finally, I need to mention the World Fantasy Award winners. We missed the award presentation, but here are the nominees and winners. Congratulations to them all, and I am particularly happy with Kij Johnson's award for the utterly magnificent Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe. And I should also add special congratulations to Neile Graham, another old friend from the much-missed Golden Age of the SFF.Net newsgroups. I did have a chance to finally meet Neile in the flesh, and talk with her for a bit.

BEST NOVEL

- The Sudden Appearance of Hope by Claire North

- Borderline by Mishell Baker

- Roadsouls by Betsy James

- The Obelisk Gate by N.K. Jemisin

- Lovecraft Country by Matt Ruff

BEST LONG FICTION

- The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe by Kij Johnson

- The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle

- Every Heart a Doorway by Seanan McGuire

- “Bloodybones” by Paul F. Olson

- A Taste of Honey by Kai Ashante Wilson

BEST SHORT FICTION

- “Das Steingeschöpf” by G.V. Anderson

- “Our Talons Can Crush Galaxies” by Brooke Bolander

- “Seasons of Glass and Iron” by Amal El-Mohtar

- “Little Widow” by Maria Dahvana Headley

- “The Fall Shall Further the Flight in Me” by Rachael K. Jones

BEST ANTHOLOGY

- Dreaming in the Dark edited by Jack Dann

- Clockwork Phoenix 5 edited by Mike Allen

- Children of Lovecraft edited by Ellen Datlow

- The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2016 edited by Karen Joy Fowler & John Joseph Adams

- The Starlit Wood edited by Dominik Parisien & Navah Wolfe

BEST COLLECTION

- A Natural History of Hell by Jeffrey Ford

- Sharp Ends by Joe Abercrombie

- On the Eyeball Floor and Other Stories by Tina Connolly

- Vacui Magia by L.S. Johnson

- The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories by Ken Liu

BEST ARTIST

- Jeffrey Alan Love

- Greg Bridges

- Julie Dillon

- Paul Lewin

- Victo Ngai

SPECIAL AWARD, PROFESSIONAL

- Michael Levy & Farah Mendlesohn, for Children’s Fantasy Literature: An Introduction

- L. Timmel Duchamp, for Aqueduct Press

- C.C. Finlay, for editing F&SF

- Kelly Link, for contributions to the genre

- Joe Monti, for contributions to the genre

SPECIAL AWARD, NON-PROFESSIONAL

- Neile Graham, for fostering excellence in the genre through her role as Workshop Director, Clarion West

- Scott H. Andrews, for Beneath Ceaseless Skies

- Malcolm R. Phifer & Michael C. Phifer, for their publication The Fantasy Illustration Library, Volume Two: Gods and Goddesses

- Lynne M. Thomas & Michael Damian Thomas, for Uncanny

- Brian White, for Fireside Fiction Company

Here are links to all five installments of this con report:

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Sunday, December 3, 2017

World Fantasy Convention, 2017, Part IV: Day 3

World Fantasy Convention, 2017, Part IV: Day 3

I've finally got back to this report -- I have been distracted by things like Thanksgiving and the deadline for my most recent Locus column. Alas, that means my memory has gobbled up even more names of people I met, which stinks. I apologize to the many I've forgotten.

Saturday morning we skipped anything elaborate for breakfast, settling for snacking in the con suite. I also took the opportunity to work out, as we also did some laundry. The only other con member I recognized in the workout room was Tananarive Due, but I'm sure everyone else was there another time!

Mary Ann and I both wanted to go to the panel "Karen Joy Fowler in Conversation", an interview conducted by Kelly Link. (Fowler is one of Mary Ann's favorite writers.) This was very enjoyable and interesting. Karen talked about her -- somewhat idyllic-seeming -- childhood in Bloomington, IN and the way that was disrupted when her father took a position at Stanford when she was 11. [Coincidentally, we ate at a restaurant in Bloomington the Saturday after Thanksgiving, on the way back from my brother's house in Indianapolis, and visiting my son's gf in Elletsville, a town next to Bloomington.] She discussed her academic career, in which she took a Bachelors and a Masters in Political Science (the first concentrating on Southwest Asia, the second in East Asia (China, Korea, and Japan) because UC Davis didn't have a program about Southwest Asia.) Her approach to a writing career was interesting -- she wanted to take ballet, and after injuries sustained courtesy of the police during a protest, she thought that impossible, but her husband bought her ballet lessons anyway, which she took until the presence of "16-year-olds who could touch their knees to their ears" got too frustrating. A writing group provided her a replacement evening to herself. Eventually she started selling her stories, and then her novels.

She discussed the difference between her stories and her novels, and some little stories about her experience with workshops, including Clarion; both as student and instructor; and also some stories about the public life of the writer. I was particularly struck by her mention of her original writers' group, which is still active. Alas, she said, all the members of the group are so concerned with rejection that they won't submit their stories anywhere, so they are writing, in essence, for an audience of seven.

After that, I had nothing until my own panel, my only one this con, at 3. That meant it was a good time for a Dealers' Room visit, and then lunch. I haven't mentioned the Dealers' Room much yet -- I actually visited it several times, though I didn't buy all that much. It was a really fine, very literary-oriented, room. I spent plenty of time at the Small Beer Press table, at Dave Willoughby's table, at Greg Ketter's Dream Haven Books table, at the Tachyon Books and Fairmont Press displays, and of course at Sally Kobee's booth. I am sure I am missing some, too ... -- yes, that's right, Larry Hallack as well. Talked at some length with Patrick Swenson, Richard Warren, Jim Van Pelt, and others.

For lunch we were determined to get Barbeque. John Joseph Adams had recommended a place, I think it was Rudy's Country Store, and we planned to try that but by the time we left we were running out of time, so we picked a closer place, the Big Bib. Once again we were vaguely disappointed by Texas Barbeque -- the Big Bib was OK, but nothing special.

We got back with just a little time to spare before my panel. I ran into Jack Skillingstead, whom I've met before a couple of times, and began talking to him, mentioning that I work at Boeing, as he once did. Jack looked a bit puzzled, then the light dawned. He hadn't recognized me (because of beard) -- and he said he thought to himself "The only guy I know in SF who also works at Boeing is Rich Horton ..." -- then the other shoe fell. Nancy Kress came out of the panel she'd been at about then, in which she had gotten into a bit of a heated discussion with one of the panelists. We talked for a bit, and it was time for my panel.

The subject was the best short fiction of 2017. I had printed a list of my favorite stories of the year, trimmed to include only Fantasy. In the event, we opened up the discussion to SF as well, but really we concentrated mainly on Fantasy. The other panelists were Ellen Datlow, Scott Andrews, and C. C. Finlay. I thought the panel went very well. I don't have a summary to give -- it would end up being too top-heavy on my choices, because my memory is crummy. Someone in the audience was recording it, I think, and others were taking notes.