Here's a review of arguably Vernor Vinge's most famous novel, and my personal favorite among his works, that I wrote when the book first appeared. Today is Vinge's 74th birthday, so I'm reposting it, in the same format I originally used when I first put it on my then new web page. (That page is now gone.)

Review Date: 28 April 1999

A Deepness in the Sky, by Vernor Vinge

Tor Books, New York, NY, March 1999

$27.95 (US), ISBN: 0-312-85683-0

Review Copyright 1999 by Rich Horton

This is a wonderful SF novel. It's the first novel in a while to really engage me on the sense of wonder level, and to again awaken the feelings of awe and of "I want to be there" that were so central to my early reading of SF. I was complaining earlier about books like Jablokov's Deepdrive, and wondering if the fault lay in me. I mean: that book (Deepdrive) is full of neat ideas, original ideas, and I thought they were well handled, and the story was good. But I never felt fully engaged, never felt "awe". I still suppose the fault may be in my jaded self, but A Deepness in the Sky proves that its still possible to really knock me out SFnally.

I'll briefly summarize the plot, hopefull avoiding spoilers. The book is set perhaps 8000 years in our future. Two starfaring human civilizations reach an anomalous astronomical object at the same time. One of the civilizations is the Qeng Ho, a loosely organized group of traders (reminiscent of Poul Anderson's Kith (this book is dedicated to Anderson) and of Robert A. Heinlein's Traders from Citizen of the Galaxy). The other is called the Emergent civilization (that name is one of many inspired coinages by Vinge). The astronomical object is something called the On/Off star, which shines for only 35 years then is a brown dwarf for the rest of its 250 year period. That's interesting enough, but what draws the two human groups is the presence of radio signals: an alien technological civilization has at last been discovered.

The Emergents turn out to be very authoritarian, and they double-cross the Qeng Ho after having agreed to a cooperative exploration of the planet. However the Qeng Ho fight back, and the humans end up losing interstellar capability. One narrative thread thus follows the human characters as they wait for the On/Off star to ignite, and for the aliens to (with their help) develop a sufficient tech level to rebuild the starships. This thread also shows the Qeng Ho resistance to the Emergent rule. The other main narrative thread follows the Spiders, the arachnoid intelligent natives of the On/Off star's single planet. These beings have long adapted to their sun's peculiarity, by hibernating through the "Dark". But one culture, led by an endearing genius named Sherkaner Underhill, has begun to develop ways of living awake through the Dark time. But they are opposed by suspicious neighbors. And the human watchers begin to subtly interfere. The whole story culminates in a terrifically exciting finish, one which intrigues at the level of action-filled resolution of multiple plots, and also at the level of revelations of the solutions to a number of ingenious scientific puzzles, and thirdly at the level of satisfying emotional thematic resolutions to the journeys of a number of characters. It's uplifting without being unrealistic or mawkish.

There are flaws, though to some extent the flaws are, I would say, necessary. This book is, I think, what Debra Doyle has called a "Romance", as such demanding larger than life characters and events. In this way, the main "flaws" are the somewhat pulpish nature of the plot and characters. But as I hint, I don't find these flaws serious. Indeed, they might really be necessary, indeed virtues, in the context of this sort of book. But it should be said that the plot depends on a few coincidences, and on things like the villains deciding not to kill the good guys because they're not sure the good guys are conspiring against them. (These villains are so bad, I don't see why they wouldn't just figure, "Better safe than sorry!", and kill them anyway (or, in the context of the book, do something worse).) And the characters feature some extremes: most obviously the alien scientist who is just an awesome genius, and who appears at the perfect time in their society. The human characters also include some remarkable folk. And the villains are really really really bad. Gosh, they're bad. But that works, too, because their worst feature is original and scary and believable and a neat SF idea.

Good stuff: with Vinge, I suppose I always think ideas first. He has come up with several. First, his concept of an extended human future in space with strict light-speed limits (as far as anyone in this book knows), is very well-worked out and believable and impressive and fun. It depends on basically three pieces of extrapolation: ramships that can get to about .3c, lifespans extended to about 500 years, and near-perfect suspended animation or coldsleep. The second neat idea is the On/Off star. The idea of a star that shines for 35 or so years and turns off for 210 years is neat, and then giving it a planet and a believable set of aliens is great fun. The aliens are really great fun too: they are too human in how they are presented, but Vinge neatly finesses this issue, in at least a half-convincing way, and he shows us glimpses that suggest real alienness, too. (Include some very nice cultural touches.) The third especially neat idea I won't mention because it might be too much of a spoiler, but the key "tech" of the bad guys is really scary, and a neat SFnal idea. And handled very well, and subtly.

As I said, I found the plot inspiring as well. This is a very long book, about 600 pages, but I was never bored. Moreover, as Patrick Nielsen Hayden has taken pains to point out, the prose in this book is quite effective. I believe Patrick used some such term as "full throated scientifictional roar". Without necessarily understanding exactly what he meant by that, the prose definitely works for me, and in ways which seem possibly particularly "scientifictional" in nature. One key factor here is names: names of characters, for one thing. Vinge's names of humans: Trixia Bonsol, Rixer Brughel, Tomas Nau, and so on, seem well chosen in several ways: they are recognizably human, and linked to present day languages, but just different enough to seem strange, and they (to my ears) sound good. His alien names are also fairly poetic, and both different and familiar sounding. (They are explicitly human coinages: a key point.) Thus: Sherkaner Underhill, Victory Smith, Hrunkner Unnerby. Mileage may vary, but I really liked these names. They certainly beat unpronounceable names, and names with non-alphabetic characters, and the like. The names of technological devices and future societies are also evocative. Examples from the humans include the Emergent society (a name with a double meaning), the Focus virus, and localizers; one alien example is videomancy.

This book is a "prequel" to Vinge's excellent previous novel A Fire Upon the Deep, but it is readable entirely without knowledge of the other book. However, having read A Fire Upon the Deep does allow the reader of A Deepness in the Sky some additional pleasures (and ironies): in particular, speculation about the true nature of the On/Off star, and about the evolutionary history of the Spiders. Also, a main character of this book was also a significant character in the previous book, and knowledge of this character's fate adds a certain frisson to the events depicted in A Deepness in the Sky.

In summary, this is an outstanding SF novel. It marries clever hard SF ideas, a rousing story, involving characters, and several interleaved, emotionally and intellectually compelling, themes. The themes are fine and fundamental to SF: involving the value of exploration and scientific knowledge, the value of freedom and thesacrifices of freedom, the desirability and costs of the dream of Empire, and the question "What would I give up to be smarter ... better ... more focussed?"

Tuesday, October 2, 2018

Birthday Review: Rainbows End, by Vernor Vinge

Birthday Review: Rainbows End, by Vernor Vinge

a review by Rich Horton

I wrote this review back in 2006 when the book came out. It won the Hugo for Best Novel the following year, though my sense is that it hasn't lasted in the public imagination the way Vinge's other novels have. Today is Vinge's 74th birthday, so I'm reposting it.

Vernor Vinge is now officially a full-time writer, having retired from his day job as a professor of Computer Science at the University of California at San Diego. So fans hoped his new novel would come more quickly, but in fact it's been 7 years. Oh well, it takes as long as it takes. Rainbows End is certainly worth the wait.

Interestingly, it is set at UCSD, and the main character is a former professor there -- though a poet, not a computer scientist. He is Robert Gu, apparently the leading poet of our time (that would be now). But as of about 20 years from now, he has been in a nursing home for years, with Alzheimer's (or some other form of dementia), and other maladies of old age. But he has been cured -- indeed he has hit the jackpot in the "heavenly minefield" of 21st Century medicine.

Robert's son and daughter-in-law, it turns out, are highly placed individuals on the U.S. side in the Great Powers' continuing war against chaos -- against the possibility of various varieties of WOMD being wielded against the whole world. One other key individual is Alfred Vaz, an Indian intelligence head. He and two of his colleagues from Europe and Japan have uncovered a plot to deliver a "YGBM" virus in a clever fashion. YGBM means "You Gotta Believe Me": that is, mind control. They recruit an helper, who they meet only in virtual space, called the Rabbit, who will assist them in infiltrating the biolabs near UCSD where they suspect the virus is under development. The kicker is that the man behind this project is Vaz himself -- but he, of course, will use this power only for good -- he sees it as the only way to control the bad guys in the world. So he needs to play his colleagues and the Rabbit very carefully. But the Rabbit's abilities in the virtual world are quite remarkable.

Inevitably, Robert Gu, his son and daughter-in-law, and his granddaughter Miri, become enmeshed, without their knowledge, in all this plotting. But the story is only partly about Alfred Vaz's machinations. It's also about Robert coming to terms with his new quasi-youth: his new abilities, such as an interest in electronics, and his terrible losses, such as his ability to write poetry. But he may have lost something else: it seems that in his prior life he was a prime jerk, driving away his wife and all his colleagues with simple nastiness. His son mostly hates him, certainly distrusts him. But has he changed?

All this is SFnally fascinating, very scary. And indeed the novel is interesting in the way that it's not quite clear who the heroes are -- well, no, it is clear: Robert Gu and Juan Orozco and Miri Gu are the heroes. But they have been coopted to work for bad guys. Maybe. Or sort of bad guys. And anyway lots of the story is not about that plotty stuff, but rather about Robert dealing with his new "youth" and his lost poetic talents, and Miri dealing with family issues, and Juan dealing with his own relative poverty and poor education ... in the end, the novel is quite satisfying as a look at pretty believable characters in a somewhat believable alternate future (I can't help but thinking that this future doesn't make sense starting from now, but maybe from 20 years ago ...). And then behind it all lurks a very scary, and only partly resolved, big story about a future balanced between terrorist chaos and even scarier order imposed by mind control. I think this is a surprisingly subtle triumph from one of the field's best pure SF writers.

a review by Rich Horton

I wrote this review back in 2006 when the book came out. It won the Hugo for Best Novel the following year, though my sense is that it hasn't lasted in the public imagination the way Vinge's other novels have. Today is Vinge's 74th birthday, so I'm reposting it.

Vernor Vinge is now officially a full-time writer, having retired from his day job as a professor of Computer Science at the University of California at San Diego. So fans hoped his new novel would come more quickly, but in fact it's been 7 years. Oh well, it takes as long as it takes. Rainbows End is certainly worth the wait.

Interestingly, it is set at UCSD, and the main character is a former professor there -- though a poet, not a computer scientist. He is Robert Gu, apparently the leading poet of our time (that would be now). But as of about 20 years from now, he has been in a nursing home for years, with Alzheimer's (or some other form of dementia), and other maladies of old age. But he has been cured -- indeed he has hit the jackpot in the "heavenly minefield" of 21st Century medicine.

Robert's son and daughter-in-law, it turns out, are highly placed individuals on the U.S. side in the Great Powers' continuing war against chaos -- against the possibility of various varieties of WOMD being wielded against the whole world. One other key individual is Alfred Vaz, an Indian intelligence head. He and two of his colleagues from Europe and Japan have uncovered a plot to deliver a "YGBM" virus in a clever fashion. YGBM means "You Gotta Believe Me": that is, mind control. They recruit an helper, who they meet only in virtual space, called the Rabbit, who will assist them in infiltrating the biolabs near UCSD where they suspect the virus is under development. The kicker is that the man behind this project is Vaz himself -- but he, of course, will use this power only for good -- he sees it as the only way to control the bad guys in the world. So he needs to play his colleagues and the Rabbit very carefully. But the Rabbit's abilities in the virtual world are quite remarkable.

Inevitably, Robert Gu, his son and daughter-in-law, and his granddaughter Miri, become enmeshed, without their knowledge, in all this plotting. But the story is only partly about Alfred Vaz's machinations. It's also about Robert coming to terms with his new quasi-youth: his new abilities, such as an interest in electronics, and his terrible losses, such as his ability to write poetry. But he may have lost something else: it seems that in his prior life he was a prime jerk, driving away his wife and all his colleagues with simple nastiness. His son mostly hates him, certainly distrusts him. But has he changed?

All this is SFnally fascinating, very scary. And indeed the novel is interesting in the way that it's not quite clear who the heroes are -- well, no, it is clear: Robert Gu and Juan Orozco and Miri Gu are the heroes. But they have been coopted to work for bad guys. Maybe. Or sort of bad guys. And anyway lots of the story is not about that plotty stuff, but rather about Robert dealing with his new "youth" and his lost poetic talents, and Miri dealing with family issues, and Juan dealing with his own relative poverty and poor education ... in the end, the novel is quite satisfying as a look at pretty believable characters in a somewhat believable alternate future (I can't help but thinking that this future doesn't make sense starting from now, but maybe from 20 years ago ...). And then behind it all lurks a very scary, and only partly resolved, big story about a future balanced between terrorist chaos and even scarier order imposed by mind control. I think this is a surprisingly subtle triumph from one of the field's best pure SF writers.

Monday, October 1, 2018

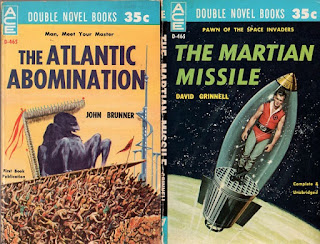

A Little Known Ace Double: The Atlantic Abomination, by John Brunner/The Martian Missile, by David Grinnell

Ace Double Reviews, 65: The Atlantic Abomination, by John Brunner/The Martian Missile, by David Grinnell (#D-465, 1960, $0.35)

I'm reposting this Ace Double review on the occasion of Donald A. Wollheim's birthday: he'd have been 104. Alas, I'm not very nice to his book, but, then, it's not a very good book.

This one qualifies as a rather randomly chosen Ace Double -- on the one hand, I like Brunner, on the other hand, here's an opportunity to review Donald Wollheim (who used "David Grinnell" as a pseudonym for much of his fiction) back to back.

Both of these novels are about 43,000 words long. As far as I know this is the first publication of The Atlantic Abomination in any form, though I may have missed a shorter magazine version under another title. The Martian Missile was first published in 1959 by Thomas Bouregy and Co. Which means some other editor evidently approved of it -- good thing! since I would have been pretty annoyed had Wollheim chosen his own piece of utter garbage! (That other editor would like have been Robert A. W. Lowndes.)

The Atlantic Abomination opens with an alien being panicking as his world seems to be falling apart. We soon gather that Earth, long ago, has been dominated by a few aliens of a species with special telepathic powers. But geological catastrophes are ruining this early human "civilization", and at least one alien escapes to a specially prepared lair.

Fast forward to the 20th Century, and an deep ocean expedition, using special technology to allow exploration of the ocean bed. The explorers happen upon a mysterious installation, which of course is the lair of the evil alien. The rest of the novel is readily enough predicted -- the alien awakes and takes over as many humans as he can. He proceeds to the East Coast of the US and enslaves thousands. An international effort attempts to stop him, with some success, but the alien seems to be figuring things out. Our hero is enslaved, but his new wife (both oceanologists from the original expedition) remains free, but he manages somehow to escape. Does humanity survive? Well of course.

I am being somewhat sarcastic, a bit unfairly. This is certainly nothing special as a novel, but in following its very predictable path, it does entertain. Brunner was just a damn good writer of, for lack of a more precise word, pulp. He always gave value for money. I enjoyed the novel, though I don't think I'll remember it or reread it.

The Martian Missile can also be described as "pulp". 30s pulp. Really BAD 30s pulp. I suppose Wollheim may have written this in 1958 or so, but it sure reads, with its scientific and astronomical stupidities, like it was written in 1931.

A small-time criminal, hiding out in the desert, happens across a crashed alien spaceship. He rescues the alien, only to have the alien implant a bomb or something that will go off in a few years if he doesn't take a special message to the alien's fellows. Naturally he figures that this "message" might mean no good for humanity, but he doesn't see an alternative.

So he sneaks aboard a Russian rocket, and manages to get to the moon. He is able to rendezvous with various planted alien ships, and he proceeds to Mars, Jupiter, and finally to Pluto. Needless to say the description of the conditions on these planets are scientifically ridiculous. Our hero becomes aware of a cosmic battle between good, bad, and indifferent aliens, and he is able to figure out a way to play them off against each other and both save Earth and save his skin.

On the whole this is pretty much SF at its worst. I've read other Wollheim/Grinnell novels, and none of them make me think Wollheim's writing career is anything to be rediscovered, this has to qualify as below his usual standard.

This one qualifies as a rather randomly chosen Ace Double -- on the one hand, I like Brunner, on the other hand, here's an opportunity to review Donald Wollheim (who used "David Grinnell" as a pseudonym for much of his fiction) back to back.

|

| (Covers by Ed Emshwiller and Ed Valigursky) |

The Atlantic Abomination opens with an alien being panicking as his world seems to be falling apart. We soon gather that Earth, long ago, has been dominated by a few aliens of a species with special telepathic powers. But geological catastrophes are ruining this early human "civilization", and at least one alien escapes to a specially prepared lair.

Fast forward to the 20th Century, and an deep ocean expedition, using special technology to allow exploration of the ocean bed. The explorers happen upon a mysterious installation, which of course is the lair of the evil alien. The rest of the novel is readily enough predicted -- the alien awakes and takes over as many humans as he can. He proceeds to the East Coast of the US and enslaves thousands. An international effort attempts to stop him, with some success, but the alien seems to be figuring things out. Our hero is enslaved, but his new wife (both oceanologists from the original expedition) remains free, but he manages somehow to escape. Does humanity survive? Well of course.

I am being somewhat sarcastic, a bit unfairly. This is certainly nothing special as a novel, but in following its very predictable path, it does entertain. Brunner was just a damn good writer of, for lack of a more precise word, pulp. He always gave value for money. I enjoyed the novel, though I don't think I'll remember it or reread it.

The Martian Missile can also be described as "pulp". 30s pulp. Really BAD 30s pulp. I suppose Wollheim may have written this in 1958 or so, but it sure reads, with its scientific and astronomical stupidities, like it was written in 1931.

A small-time criminal, hiding out in the desert, happens across a crashed alien spaceship. He rescues the alien, only to have the alien implant a bomb or something that will go off in a few years if he doesn't take a special message to the alien's fellows. Naturally he figures that this "message" might mean no good for humanity, but he doesn't see an alternative.

So he sneaks aboard a Russian rocket, and manages to get to the moon. He is able to rendezvous with various planted alien ships, and he proceeds to Mars, Jupiter, and finally to Pluto. Needless to say the description of the conditions on these planets are scientifically ridiculous. Our hero becomes aware of a cosmic battle between good, bad, and indifferent aliens, and he is able to figure out a way to play them off against each other and both save Earth and save his skin.

On the whole this is pretty much SF at its worst. I've read other Wollheim/Grinnell novels, and none of them make me think Wollheim's writing career is anything to be rediscovered, this has to qualify as below his usual standard.

Birthday Review: A Princess of Roumania, by Paul Park

Birthday Review: A Princess of Roumania, by Paul Park

a review by Rich Horton

Paul Park turns 64 today, and in honor of his birthday, I'm posting this review I did back in 2005 on SFF Net. As it happens, I reviewed the second and third volumes of the series this novel starts for SF Site. Not the last, though.

Paul Park's A Princess of Roumania, from 2005, is the beginning of his tetralogy also called A Princess of Roumania. In a way this seems a departure for Park, previously the writer of an audacious SF trilogy, The Starbridge Chronicles; a difficult SF novel, Coelestis, and two very religiously-focussed historical novels, The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. None of these books (with the arguable exception of his first trilogy) were terribly commercial. Indeed, none were fantasies, though they are hardly traditional SF, nor traditional historical fiction. By contrast A Princess of Roumania is certainly fantasy, and arguably Young Adult fantasy (the Washington Post compares it (not terribly sensibly) to Harry Potter and Oz); and on the whole I would say it has more commercial potential than his previous books. But in so saying I do not mean to say it is less ambitious than his earlier works, or less imaginative -- indeed, it is a very fine novel, and promises to open a fascinating series.

Paul Park's A Princess of Roumania, from 2005, is the beginning of his tetralogy also called A Princess of Roumania. In a way this seems a departure for Park, previously the writer of an audacious SF trilogy, The Starbridge Chronicles; a difficult SF novel, Coelestis, and two very religiously-focussed historical novels, The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. None of these books (with the arguable exception of his first trilogy) were terribly commercial. Indeed, none were fantasies, though they are hardly traditional SF, nor traditional historical fiction. By contrast A Princess of Roumania is certainly fantasy, and arguably Young Adult fantasy (the Washington Post compares it (not terribly sensibly) to Harry Potter and Oz); and on the whole I would say it has more commercial potential than his previous books. But in so saying I do not mean to say it is less ambitious than his earlier works, or less imaginative -- indeed, it is a very fine novel, and promises to open a fascinating series.

Miranda Popescu is a 15 year old girl in a college town in upstate New York in about the present day. She was adopted from Romania in the chaos following the uprising against Ceausescu. As the novel opens she befriends a lonely one-armed boy, Peter Gross. Her other special friend is a popular girl named Andromeda. Soon they meet a sinister group of teenagers who have just moved to their town, and suddenly their school is set afire, risking Miranda's special keepsakes from Romania: some coins and jewelry, and in particular a remarkable book called The Essential History, which describes world history from an unusual viewpoint.

In a completely different world we meet the Baroness Nicola Ceausescu, formerly a prostitute then a successful actress and dancer, who became the second wife of a much older man. This man was involved in an intrigue which led to the execution of Miranda's father, the exile of her mother to Germany, and the financial ruin of her Aunt, Princess Aegypta Schenk von Schenk, half-German and half a descendant of the White Tyger, Miranda Brancoveanu, who saved Roumania centuries before.

It seems to be Aegypta's hope that Miranda Popescu is the new White Tyger, who will save Roumania from her corrupt current Empress, and from the threat of German invasion. Both Aegypta and Nicola are sorceresses, and Aegypta, we soon gather, has created an artificial world, our world, in which she has hidden Miranda, as well as two loyal retainers, who have been incarnated as Peter and Andromeda.

Nicola has managed to send some people to that world, to find Miranda and bring her back -- both realize that if she is the new White Tyger, control of this teenager will be critical. Nicola, furthermore, is intriguing with a German envoy, thus betraying both her nominal political ally, the Empress, and of course her longtime enemy, the Princess Aegypta.

Nicola's schemes succeed in a limited manner, and Miranda, Peter, and Andromeda all end up in the "real world": our world, and its creating book, having been destroyed. (Apparently.) But they are marooned in the wilds of America, inhabited mainly by savage refugees from earthquake-shattered England. Nicola, however, loses control of her plans, and is forced to turn against her erstwhile German friends, though she does come into possession of a powerful gem, Kepler's Eye, a tourmaline. (It is surely significant that volume II of the series is called The Tourmaline.) She finds herself accused of a murder she didn't commit, while racked with guilt over a murder she did commit. Miranda, in dream contact with Aegypta, a woman she doesn't know, struggles to make her way with Peter, Andromeda, and an obsessed tool of Nicola's, Major Raevsky, to Albany and eventually to a ship to Roumania. Or, she hopes, perhaps back to "our" world. The German Elector of Ratisbon, an illegal sorcerer himself, is trying to find Miranda, and also the tourmaline.

It's a thoroughly interesting novel. In particular, the characters of the villains are wonderfully realized, especially Nicola Ceausescu, who is a certainly a bad person, but at the same time a person with whom we sympathize: and someone who is sometimes on the "right" side. The magical parts are very original, believable (in context), and impressive. There is no real resolution -- this is after all the first of a tetralogy. But I'll be eagerly reading on.

a review by Rich Horton

Paul Park turns 64 today, and in honor of his birthday, I'm posting this review I did back in 2005 on SFF Net. As it happens, I reviewed the second and third volumes of the series this novel starts for SF Site. Not the last, though.

Paul Park's A Princess of Roumania, from 2005, is the beginning of his tetralogy also called A Princess of Roumania. In a way this seems a departure for Park, previously the writer of an audacious SF trilogy, The Starbridge Chronicles; a difficult SF novel, Coelestis, and two very religiously-focussed historical novels, The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. None of these books (with the arguable exception of his first trilogy) were terribly commercial. Indeed, none were fantasies, though they are hardly traditional SF, nor traditional historical fiction. By contrast A Princess of Roumania is certainly fantasy, and arguably Young Adult fantasy (the Washington Post compares it (not terribly sensibly) to Harry Potter and Oz); and on the whole I would say it has more commercial potential than his previous books. But in so saying I do not mean to say it is less ambitious than his earlier works, or less imaginative -- indeed, it is a very fine novel, and promises to open a fascinating series.

Paul Park's A Princess of Roumania, from 2005, is the beginning of his tetralogy also called A Princess of Roumania. In a way this seems a departure for Park, previously the writer of an audacious SF trilogy, The Starbridge Chronicles; a difficult SF novel, Coelestis, and two very religiously-focussed historical novels, The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. None of these books (with the arguable exception of his first trilogy) were terribly commercial. Indeed, none were fantasies, though they are hardly traditional SF, nor traditional historical fiction. By contrast A Princess of Roumania is certainly fantasy, and arguably Young Adult fantasy (the Washington Post compares it (not terribly sensibly) to Harry Potter and Oz); and on the whole I would say it has more commercial potential than his previous books. But in so saying I do not mean to say it is less ambitious than his earlier works, or less imaginative -- indeed, it is a very fine novel, and promises to open a fascinating series.Miranda Popescu is a 15 year old girl in a college town in upstate New York in about the present day. She was adopted from Romania in the chaos following the uprising against Ceausescu. As the novel opens she befriends a lonely one-armed boy, Peter Gross. Her other special friend is a popular girl named Andromeda. Soon they meet a sinister group of teenagers who have just moved to their town, and suddenly their school is set afire, risking Miranda's special keepsakes from Romania: some coins and jewelry, and in particular a remarkable book called The Essential History, which describes world history from an unusual viewpoint.

In a completely different world we meet the Baroness Nicola Ceausescu, formerly a prostitute then a successful actress and dancer, who became the second wife of a much older man. This man was involved in an intrigue which led to the execution of Miranda's father, the exile of her mother to Germany, and the financial ruin of her Aunt, Princess Aegypta Schenk von Schenk, half-German and half a descendant of the White Tyger, Miranda Brancoveanu, who saved Roumania centuries before.

It seems to be Aegypta's hope that Miranda Popescu is the new White Tyger, who will save Roumania from her corrupt current Empress, and from the threat of German invasion. Both Aegypta and Nicola are sorceresses, and Aegypta, we soon gather, has created an artificial world, our world, in which she has hidden Miranda, as well as two loyal retainers, who have been incarnated as Peter and Andromeda.

Nicola has managed to send some people to that world, to find Miranda and bring her back -- both realize that if she is the new White Tyger, control of this teenager will be critical. Nicola, furthermore, is intriguing with a German envoy, thus betraying both her nominal political ally, the Empress, and of course her longtime enemy, the Princess Aegypta.

Nicola's schemes succeed in a limited manner, and Miranda, Peter, and Andromeda all end up in the "real world": our world, and its creating book, having been destroyed. (Apparently.) But they are marooned in the wilds of America, inhabited mainly by savage refugees from earthquake-shattered England. Nicola, however, loses control of her plans, and is forced to turn against her erstwhile German friends, though she does come into possession of a powerful gem, Kepler's Eye, a tourmaline. (It is surely significant that volume II of the series is called The Tourmaline.) She finds herself accused of a murder she didn't commit, while racked with guilt over a murder she did commit. Miranda, in dream contact with Aegypta, a woman she doesn't know, struggles to make her way with Peter, Andromeda, and an obsessed tool of Nicola's, Major Raevsky, to Albany and eventually to a ship to Roumania. Or, she hopes, perhaps back to "our" world. The German Elector of Ratisbon, an illegal sorcerer himself, is trying to find Miranda, and also the tourmaline.

It's a thoroughly interesting novel. In particular, the characters of the villains are wonderfully realized, especially Nicola Ceausescu, who is a certainly a bad person, but at the same time a person with whom we sympathize: and someone who is sometimes on the "right" side. The magical parts are very original, believable (in context), and impressive. There is no real resolution -- this is after all the first of a tetralogy. But I'll be eagerly reading on.

Sunday, September 30, 2018

Birthday Review: Theodora Goss stories

Birthday Review: Short Fiction from Theodora Goss

Theodora Goss is one of my favorite SF/F writers, bar none; and especially so if you consider writers of short fiction who began publishing in this millennium. (Add Genevieve Valentine and C. S. E. Cooney to that list, and I note that those are all women without comment.) Today is her birthday, and so here is my compilation of most of the reviews I've done of her work for Locus.

(Locus, April 2002)

I reviewed her first story, "The Rose in Twelve Petals", from Realms of Fantasy, for Locus, in the third monthly column I ever wrote. I am always proud when I realize the potential of a new writer from the beginning -- though the pride belongs to them! Alas, my electronic copy of that review is corrupted, and I can't read it. But here's the excerpt from the Small Beer Press page:

One of the most impressive debuts I can recall. Fairy tale retellings are a dime a dozen, and Sleeping Beauty ones probably as common as any, so this story has to be special to stand out, and special it is.

(Locus, January 2004)

Theodora Goss's "Lily, With Clouds" (Alchemy #1) tells of a woman coming home to her sister's house to die, accompanied by her dead husband's mistress, and her husband's paintings. Mostly it's simply of picture of three woman: the conventional, prudish, sister; the once rebellious dying woman; and the rather odd mistress -- but the ending is just beautiful, an inevitable surprise.

(Locus, May 2004)

In Polyphony 4, Theodora Goss continues to impress with "The Wings of Meister Wilhelm", in which a girl takes violin lessons from a German newly arrived at her Southern town. She learns he has a strange desire -- to make a flying machine and reach the flying city of Orillion. Goss blends a heartfelt depiction of a girl growing up with a lovely portrait of a man's dream, and at the end adds darker strands to her tapestry.

(Locus, September 2005)

Theodora Goss offers "A Statement in the Case" (Realms of Fantasy, August). An old man tells a policeman of his friendship with an apothecary. The apothecary is an immigrant, and he runs an old-fashioned store: one might say "charming". All this changes when he marries. Slowly we learn the apothecary's strange secrets, his sadness, and why the policeman is interested.

(Locus, December 2005)

First, Strange Horizons -- which, however, is no longer exactly "less prominent". But they do feature one of the best stories of the month -- indeed, of the year: Theodora Goss’s "Pip and the Fairies". Philippa’s late mother wrote children’s books about a girl visiting fairyland. Philippa (Pip?) is now a successful actress, and she has bought the house her mother and she lived in, in poverty, while the books were written. These books, lately popular, were based on her childhood -- or were they? Stories she told her mother, or stories her mother made up, or real magical experiences, or some sort of fictional distillation of the problems a single mother and her child faced … Goss intertwines Philippa’s memories of her childhood, her imperfect relationship with her mother, her present day relationship with fans of the book, and passages from her mother’s books. The material is perhaps familiar but the treatment is powerfully affecting.

(Locus, April 2006)

The second issue of Fantasy Magazine has appeared. Disclaimer first -- I contribute short book reviews to this magazine. Even so, I don’t think I am wrong to praise Theodora Goss’s "Lessons With Miss Gray", in which five young women, four close friends and an outsider, take lessons in magic from the title character, who has appeared in other Goss pieces. The girls learn real magic, and they also learn (or we learn) about their characters how these (and their futures) are affected by race, class, and gender. It’s witty and involving and clearheaded -- another triumph for Goss.

(Logorrhea review, Locus, May 2007)

Theodora Goss’s "Singing of Mount Abora" plays with Coleridge instead of Tolkien -- recasting the inspiration of "Kubla Khan" in weaving together a story of an Ancient Chinese woman trying to win a dragon’s hand, a contemporary woman studying Coleridge, and Coleridge himself, in Xanadu of all places.

(Locus, June 2007)

The June Realms of Fantasy closes with a lovely Theodora Goss tale, "Princess Lucinda and the Hound of the Moon", about a Princess who is really a baby found by a childless royal couple in the woods, and her ordinary childhood, and ambitions, and what happens when she finds her real mother. Here again is a story that captivates first -- perhaps it is not especially profound but it is great fun. I thought first of George MacDonald's The Light Princess.

(Locus, December 2007)

And to a true survivor in online SF: Strange Horizons. In October I liked best Theodora Goss’s "Catherine and the Satyr". It’s set in Regency England. Catherine is unhappily married, and has left her husband. The Earl of Aberdeen has a zoo, and the zoo has a satyr. Catherine finds the satyr surprisingly well-educated, and attractive, and so ... but Goss is a subtler writer than that, and the story, in the end, suggests that marriage in a society like Catherine’s could be a cage -- like the satyr’s cage, perhaps, or even like the servitude endured by a servant Catherine unwittingly causes harm to.

(Locus, May 2009)

Apex Online’s March issue is also strong, with a couple of thematically related original stories. ... "The Puma", by Theodora Goss, returns to the famous early exemplar of human/animal chimera stories, with a survivor of the events of Wells’s Island of Dr. Moreau confronted by the beautiful puma woman who plays on his guilt to support her efforts to continue Moreau’s work, but with more control ceded to the chimeras.

(Locus, March 2010)

Last year Theodora Goss explored the aftermath of Wells’ Island of Dr. Moreau in a fine story called "The Puma". Now, at Strange Horizons in January, she gives us "The Mad Scientist’s Daughter", which features six "daughters" of mad scientists, among them Moreau’s creation Catherine, as well as Rappaccini’s daughter, and a creation of Dr. Frankenstein, and a hitherto unrevealed pair of daughters of Jekyll and Hyde. The story details their lives together, their difficulties with their unique histories and characteristics, and so on, in a very witty and intelligent fashion. [Gee, wouldn't a novel on this subject be nice? :) ]

(Locus, October 2010)

Another online magazine, Apex, unveils a new editor in August, Catherynne M. Valente. Her first issue features a lovely story from Theodora Goss, "Fair Ladies", about Rudi, a rather callow young R/u/r/i/t/a/n/i/a/n Sylvanian man who is compelled by his father to take up with an older woman -- in fact, we soon gather, his father’s old mistress. The oddly alluring woman has a secret, of course, a magical and sad secret. It’s a familiar story, but given particular resonance by the slightly dissonant angle of telling, and by the ominous historical events looming the background -- the rise of the Third Reich.

(Locus, July 2011)

"Pug", by Theodora Goss (Asimov's, July), is set in the background of one of the most famous novels of all time -- readily enough recognized though I’ll not mention which it is. But the title dog (who seems perhaps to have escaped from another novel by the same author!) has a unique characteristic -- he can travel to other worlds, and eventually the heroine of this story, a rather colorless and sickly girl, can follow him. Which perhaps gives her a life otherwise denied her. The story nicely elaborates on the circumstances of its heroine, and is just fun to read for Goss’s prose, and for the pleasure of unpicking the relationship with its source material.

(Locus, September 2012)

Finally, in the August Asimov's, I really liked Theodora Goss's "Beautiful Boys", a short piece about a certain class of young man -- "bad boys" one might call them as well as beautiful, prone to brief affairs with vulnerable women followed by abandonment. It's told by a woman researcher, and she has an explanation for them -- a science fictional one, so that the story becomes both a subtle and slightly sad look at her life, and a somewhat Sturgeonesque bit of Sfnal speculation.

(Locus, January 2014)

And "Blanchefleur", by Theodora Goss (from Paula Guran's anthology Once Upon a Time), is a long and quite traditional but very satisfying tale of a young man, regarded as the village idiot, who instead is part Fairy, and who eventually is summoned to his other family's place, where there seems to be lots of talking cats... and too a variant on the traditional three tasks. This is subversive or post-modern or revisionist, really -- but it's beautifully told and often funny and original and, well, nice.

(Locus, July 2015)

The other story I really liked in the July Lightspeed was "Cimmeria: From the Journal of Imaginary Anthropology", by Theodora Goss, in which a group of post-docs and grad students write about an imaginary country, creating history, religion, culture, etc., from scratch; then somehow find that it really exists. Did they create it? One of them ends up marrying a daughter of the Khan, and that is even stranger, as she has an identical twin who is ignored by everyone (as in Cimmeria, twins have no independent souls), but who follows them everywhere. Very Borgesian, of course, and very fine.

(Locus, January 2017)

More traditional in form, from The Starlit Wood, is "The Other Thea", by Theodora Goss, which takes the central idea of Hans Christian Andersen’s "The Shadow" (that a person might become disconnected from their shadow, which is sort of an other self, an alternate version of them), and makes a new story of it, related a couple of her best earlier stories, "Miss Emily Gray" and "Lessons with Miss Gray". Thea (surely a significant name choice!) has been drifting through life in the months since graduating from Miss Lavender’s School of Witchcraft, and she ends up drifting back to the school, where she is told that she must find her shadow, which had been cut off by her grandmother when she was just a child. So she travels to the Other Country, and, of course, does find her shadow -- or it finds her -- but who says the shadow wants anything to do with her? It’s a beautifully written story, and great fun, but perhaps a bit thin next to the Samatar story, and to my other favorite in the book.

(Locus, May 2017)

The best recent story in Tor.com comes from Theodora Goss. "Come See the Living Dryad" is told by a contemporary woman, Daphne Levitt, a scientist writing about historical "freaks", like the Elephant Man. Her motivation is her great-grandmother, who was an exhibit in the 1880s as "the Living Dryad". In reality, this woman, Daphne Merwin, suffered from Lewandowsky-Lutz dysplasia, a real condition that can lead to branch-like growths on peoples’ skin. Dr. Levitt ends up investigated her great-grandmother’s murder, for which, she learns, a man was falsely convicted. The real story turns on a familiar tale of jealousy and abuse and charlatanage. A moving story, well-framed (and, if truth be told, not really SF or Fantasy, but very much worth reading).

Theodora Goss is one of my favorite SF/F writers, bar none; and especially so if you consider writers of short fiction who began publishing in this millennium. (Add Genevieve Valentine and C. S. E. Cooney to that list, and I note that those are all women without comment.) Today is her birthday, and so here is my compilation of most of the reviews I've done of her work for Locus.

(Locus, April 2002)

I reviewed her first story, "The Rose in Twelve Petals", from Realms of Fantasy, for Locus, in the third monthly column I ever wrote. I am always proud when I realize the potential of a new writer from the beginning -- though the pride belongs to them! Alas, my electronic copy of that review is corrupted, and I can't read it. But here's the excerpt from the Small Beer Press page:

One of the most impressive debuts I can recall. Fairy tale retellings are a dime a dozen, and Sleeping Beauty ones probably as common as any, so this story has to be special to stand out, and special it is.

(Locus, January 2004)

Theodora Goss's "Lily, With Clouds" (Alchemy #1) tells of a woman coming home to her sister's house to die, accompanied by her dead husband's mistress, and her husband's paintings. Mostly it's simply of picture of three woman: the conventional, prudish, sister; the once rebellious dying woman; and the rather odd mistress -- but the ending is just beautiful, an inevitable surprise.

(Locus, May 2004)

In Polyphony 4, Theodora Goss continues to impress with "The Wings of Meister Wilhelm", in which a girl takes violin lessons from a German newly arrived at her Southern town. She learns he has a strange desire -- to make a flying machine and reach the flying city of Orillion. Goss blends a heartfelt depiction of a girl growing up with a lovely portrait of a man's dream, and at the end adds darker strands to her tapestry.

(Locus, September 2005)

Theodora Goss offers "A Statement in the Case" (Realms of Fantasy, August). An old man tells a policeman of his friendship with an apothecary. The apothecary is an immigrant, and he runs an old-fashioned store: one might say "charming". All this changes when he marries. Slowly we learn the apothecary's strange secrets, his sadness, and why the policeman is interested.

(Locus, December 2005)

First, Strange Horizons -- which, however, is no longer exactly "less prominent". But they do feature one of the best stories of the month -- indeed, of the year: Theodora Goss’s "Pip and the Fairies". Philippa’s late mother wrote children’s books about a girl visiting fairyland. Philippa (Pip?) is now a successful actress, and she has bought the house her mother and she lived in, in poverty, while the books were written. These books, lately popular, were based on her childhood -- or were they? Stories she told her mother, or stories her mother made up, or real magical experiences, or some sort of fictional distillation of the problems a single mother and her child faced … Goss intertwines Philippa’s memories of her childhood, her imperfect relationship with her mother, her present day relationship with fans of the book, and passages from her mother’s books. The material is perhaps familiar but the treatment is powerfully affecting.

(Locus, April 2006)

The second issue of Fantasy Magazine has appeared. Disclaimer first -- I contribute short book reviews to this magazine. Even so, I don’t think I am wrong to praise Theodora Goss’s "Lessons With Miss Gray", in which five young women, four close friends and an outsider, take lessons in magic from the title character, who has appeared in other Goss pieces. The girls learn real magic, and they also learn (or we learn) about their characters how these (and their futures) are affected by race, class, and gender. It’s witty and involving and clearheaded -- another triumph for Goss.

(Logorrhea review, Locus, May 2007)

Theodora Goss’s "Singing of Mount Abora" plays with Coleridge instead of Tolkien -- recasting the inspiration of "Kubla Khan" in weaving together a story of an Ancient Chinese woman trying to win a dragon’s hand, a contemporary woman studying Coleridge, and Coleridge himself, in Xanadu of all places.

(Locus, June 2007)

The June Realms of Fantasy closes with a lovely Theodora Goss tale, "Princess Lucinda and the Hound of the Moon", about a Princess who is really a baby found by a childless royal couple in the woods, and her ordinary childhood, and ambitions, and what happens when she finds her real mother. Here again is a story that captivates first -- perhaps it is not especially profound but it is great fun. I thought first of George MacDonald's The Light Princess.

(Locus, December 2007)

And to a true survivor in online SF: Strange Horizons. In October I liked best Theodora Goss’s "Catherine and the Satyr". It’s set in Regency England. Catherine is unhappily married, and has left her husband. The Earl of Aberdeen has a zoo, and the zoo has a satyr. Catherine finds the satyr surprisingly well-educated, and attractive, and so ... but Goss is a subtler writer than that, and the story, in the end, suggests that marriage in a society like Catherine’s could be a cage -- like the satyr’s cage, perhaps, or even like the servitude endured by a servant Catherine unwittingly causes harm to.

(Locus, May 2009)

Apex Online’s March issue is also strong, with a couple of thematically related original stories. ... "The Puma", by Theodora Goss, returns to the famous early exemplar of human/animal chimera stories, with a survivor of the events of Wells’s Island of Dr. Moreau confronted by the beautiful puma woman who plays on his guilt to support her efforts to continue Moreau’s work, but with more control ceded to the chimeras.

(Locus, March 2010)

Last year Theodora Goss explored the aftermath of Wells’ Island of Dr. Moreau in a fine story called "The Puma". Now, at Strange Horizons in January, she gives us "The Mad Scientist’s Daughter", which features six "daughters" of mad scientists, among them Moreau’s creation Catherine, as well as Rappaccini’s daughter, and a creation of Dr. Frankenstein, and a hitherto unrevealed pair of daughters of Jekyll and Hyde. The story details their lives together, their difficulties with their unique histories and characteristics, and so on, in a very witty and intelligent fashion. [Gee, wouldn't a novel on this subject be nice? :) ]

(Locus, October 2010)

Another online magazine, Apex, unveils a new editor in August, Catherynne M. Valente. Her first issue features a lovely story from Theodora Goss, "Fair Ladies", about Rudi, a rather callow young R/u/r/i/t/a/n/i/a/n Sylvanian man who is compelled by his father to take up with an older woman -- in fact, we soon gather, his father’s old mistress. The oddly alluring woman has a secret, of course, a magical and sad secret. It’s a familiar story, but given particular resonance by the slightly dissonant angle of telling, and by the ominous historical events looming the background -- the rise of the Third Reich.

(Locus, July 2011)

"Pug", by Theodora Goss (Asimov's, July), is set in the background of one of the most famous novels of all time -- readily enough recognized though I’ll not mention which it is. But the title dog (who seems perhaps to have escaped from another novel by the same author!) has a unique characteristic -- he can travel to other worlds, and eventually the heroine of this story, a rather colorless and sickly girl, can follow him. Which perhaps gives her a life otherwise denied her. The story nicely elaborates on the circumstances of its heroine, and is just fun to read for Goss’s prose, and for the pleasure of unpicking the relationship with its source material.

(Locus, September 2012)

Finally, in the August Asimov's, I really liked Theodora Goss's "Beautiful Boys", a short piece about a certain class of young man -- "bad boys" one might call them as well as beautiful, prone to brief affairs with vulnerable women followed by abandonment. It's told by a woman researcher, and she has an explanation for them -- a science fictional one, so that the story becomes both a subtle and slightly sad look at her life, and a somewhat Sturgeonesque bit of Sfnal speculation.

(Locus, January 2014)

And "Blanchefleur", by Theodora Goss (from Paula Guran's anthology Once Upon a Time), is a long and quite traditional but very satisfying tale of a young man, regarded as the village idiot, who instead is part Fairy, and who eventually is summoned to his other family's place, where there seems to be lots of talking cats... and too a variant on the traditional three tasks. This is subversive or post-modern or revisionist, really -- but it's beautifully told and often funny and original and, well, nice.

(Locus, July 2015)

The other story I really liked in the July Lightspeed was "Cimmeria: From the Journal of Imaginary Anthropology", by Theodora Goss, in which a group of post-docs and grad students write about an imaginary country, creating history, religion, culture, etc., from scratch; then somehow find that it really exists. Did they create it? One of them ends up marrying a daughter of the Khan, and that is even stranger, as she has an identical twin who is ignored by everyone (as in Cimmeria, twins have no independent souls), but who follows them everywhere. Very Borgesian, of course, and very fine.

(Locus, January 2017)

More traditional in form, from The Starlit Wood, is "The Other Thea", by Theodora Goss, which takes the central idea of Hans Christian Andersen’s "The Shadow" (that a person might become disconnected from their shadow, which is sort of an other self, an alternate version of them), and makes a new story of it, related a couple of her best earlier stories, "Miss Emily Gray" and "Lessons with Miss Gray". Thea (surely a significant name choice!) has been drifting through life in the months since graduating from Miss Lavender’s School of Witchcraft, and she ends up drifting back to the school, where she is told that she must find her shadow, which had been cut off by her grandmother when she was just a child. So she travels to the Other Country, and, of course, does find her shadow -- or it finds her -- but who says the shadow wants anything to do with her? It’s a beautifully written story, and great fun, but perhaps a bit thin next to the Samatar story, and to my other favorite in the book.

(Locus, May 2017)

The best recent story in Tor.com comes from Theodora Goss. "Come See the Living Dryad" is told by a contemporary woman, Daphne Levitt, a scientist writing about historical "freaks", like the Elephant Man. Her motivation is her great-grandmother, who was an exhibit in the 1880s as "the Living Dryad". In reality, this woman, Daphne Merwin, suffered from Lewandowsky-Lutz dysplasia, a real condition that can lead to branch-like growths on peoples’ skin. Dr. Levitt ends up investigated her great-grandmother’s murder, for which, she learns, a man was falsely convicted. The real story turns on a familiar tale of jealousy and abuse and charlatanage. A moving story, well-framed (and, if truth be told, not really SF or Fantasy, but very much worth reading).

Friday, September 28, 2018

A Late But Little Known Ace Double: Life with Lancelot, by John T. Phillifent/Hunting on Kunderer, by William Barton

Ace Double Reviews, 23: Life With Lancelot, by John T. Phillifent/Hunting on Kunderer, by William Barton (#48245, 1973, $0.95)

a review by Rich Horton

This is one of the last true Ace Doubles, having been published in August of 1973, the last year for the "dos-a-dos" style doubles. It features one author's first novel and only Ace Double. And it features nearly the last novel by one of the most prolific of Ace Double contributors. William Barton's Hunting on Kunderer is the "first novel", a fairly short one at some 34,000 words. John T. Phillifent wrote 16 different Ace Double halves, fourteen under the name "John Rackham", and Life With Lancelot is one of four novels he put out in 1973, the last year he published any novels. It is about 40,000 words long. One interesting note is the cover to Life With Lancelot, which is by Ed Valigursky. Valigursky was an extremely regular cover artist of Ace Double in the first decade of the series, but his last before this one was in 1965. Nice to see him return one time right at the end of the series (and indeed he did another in 1973, for Mack Reynolds' Code Duello). This was also mostly the end of his SF illustrator career, though he continued to do work for places like Popular Mechanics until he retired some time in the 1990s, and he also did some fine art.

William Barton has become fairly well known in recent years for a number of reputedly extremely dark and cynical novels, featuring lots of violence and lots of sex (sometimes rather icky sex). He often writes in collaboration with Michael Capobianco. I myself have not read any of his novels, but I have read a number of novellas in places like Asimov's and Sci Fiction, and the novellas are indeed often extremely dark and cynical, and they tend to feature plenty of violence and (sometimes icky) sex. They are also often very good -- in particular I like his two most recent Asimov's novellas: last year's "The Engine of Desire" and this year's "Off on a Starship".

Hunting on Kunderer has some sex, though it's not very icky (a bit maybe), and some violence. It's not what I'd call dark, but it is rather cynical. It's really not very good, though, not even close to as good as his later work -- the writing is at best routine, at worst clumsy, the plotting is perfunctory, the setting a bit ordinary.

Kunderer is a planet apparently consisting largely of jungles, with huge trees, and with a dominant predator much resembling a tyrannosaur. A small group arrives on the starship Wandervogel to take a hunting trip. These include Scott MacLeod, a space navy officer on leave; Uri Baruch, a 300 year old Jewish man who has just been ousted as long-time first minister of the Vinzeth Empire, and who has had his sexual organs restored to him after nearly 300 years as a eunuch; Pashai anke Soring, an alien who has been studying human sexuality; and Maryam, a whore who has been assisting Soring in his researches.

On arrival the four go off into the jungle with a guide named of all things Gilgamesh. Meanwhile, the starship has been sabotaged, and apparently only good luck got them safely to Kunderer. The captain quickly decides that one of the four passengers committed the sabotage, and he engages another guide and follows them in order to interrogate each suspect.

The action consists of a bit of hunting of the tyrannosaurs, a bit of ineffectually questioning by the Captain, a rather more effective investigation by the people repairing the starship, and other niceties such as the alien Soring trying to get Maryam to be seduced by or seduce other passengers in order to advance his scientific studies. There are a few deaths, a solution of sorts to the sabotage mystery, and a curiously upbeat (one might almost say, pasted on) ending.

I can detect traces of the future Barton in this book, but for the most part there is no indication that he would become the writer he did. A weak effort, with a couple of minor interesting touches but mostly not -- forgettable, on the whole.

In 1961 John T. Phillifent published a story called "The Stainless-Steel Knight" in If, under the "John Rackham" name. That story is the first part of the novel Life With Lancelot, which is padded out with two more stories of similar length. As far as I can tell, the two additional stories were not published elsewhere. In this book the three stories are called "Stainless Knight", "Logical Knight", and "Arabian Knight".

All three stories are set on a "Vivarian" planet, consisting of three continents, each a reserve for people living in imitation of a certain historical period. The hero is Lancelot Lake, who is given a back story in which he, a lowly spaceship technician, attempts to save a doomed spaceship, and fails, crashlanding on an alien world. He is posthumously awarded promotion to Prime G, the highest rank in Galactopol. Unfortunately for Galactopol, the aliens have super medical powers, and great interest in humans, and they save Lancelot's life, and give him extra physical strength and an alien companion, called the Shogleet. They can't do much for his brains, though.

Lancelot demands assignments worthy of his position, and as each continent is becoming destabilized -- failing to maintain their historical culture -- he goes to each one in turn. The first is a medieval culture, menaced by the appearance of a "dragon", and Lancelot must vanquish the knight who found the dragon, and then destroy the dragon (which is actually something else, as the reader readily guesses). This he does with the considerable help of the Shogleet, at the same time enjoying himself with several wives and a beautiful maiden who falls in love with him. The second is an Ancient Greek culture which has rejected the Gods, and Lancelot's job is to go down disguised as Apollo, and perform a few miracles to rekindle faith. But he and his lovestruck female technician companion end up in trouble, and the Shogleet must come up with another solution, inspired by a famous Greek comedy. The third culture is Arabian, and it is menaced by a renegade Galactic who is using the high-tech androids, afreets, and so on to rule a fictional Baghdad. Lancelot and a beautiful but sexually repressed fellow agent visit Baghdad disguised as Iskander and the Queen of Sheba, hoping to use the woman agent's charms to distract the bad guy. Unfortunately, the rat doses her with an aphrodisiac. Naturally, Lancelot ends up benefiting from her sudden compulsion for sex, while the Shogleet (with it must be said Lancelot's considerable assistance) again saves the day.

All in all, these are pretty weak stories. The core ideas are hackneyed, and Phillifent does very little new with them. The sex is a bit embarrassing -- the first story has only hints of it, but the later two, presumably written much later, both feature repressed women who fall for the alien-enhanced Lancelot, and who spend most of the story buck naked, and much of it begging for his attention. The plots are rudimentary, solved mainly by the Shogleet's conveniently scaled powers. Lancelot's character shifts a lot, too -- the basic setup is that he is a nebbish, more or less, stupid and way out of his depth and not much physically either. But by the last stories he has become somehow quite a bit more intelligent, and he seems to be rather more a physical specimen (even discounting the alien mods) than originally described.

I'm also a bit puzzled by the use of the Phillifent name. The original story was published as by "John Rackham", and "Rackham" was the name he used for all of his other Ace Doubles save one, and that one, Hierarchies, was originally an Analog serial as by "Phillifent" (which name he generally used only for his Analog stories (and some Man From Uncle tie-ins).)

a review by Rich Horton

This is one of the last true Ace Doubles, having been published in August of 1973, the last year for the "dos-a-dos" style doubles. It features one author's first novel and only Ace Double. And it features nearly the last novel by one of the most prolific of Ace Double contributors. William Barton's Hunting on Kunderer is the "first novel", a fairly short one at some 34,000 words. John T. Phillifent wrote 16 different Ace Double halves, fourteen under the name "John Rackham", and Life With Lancelot is one of four novels he put out in 1973, the last year he published any novels. It is about 40,000 words long. One interesting note is the cover to Life With Lancelot, which is by Ed Valigursky. Valigursky was an extremely regular cover artist of Ace Double in the first decade of the series, but his last before this one was in 1965. Nice to see him return one time right at the end of the series (and indeed he did another in 1973, for Mack Reynolds' Code Duello). This was also mostly the end of his SF illustrator career, though he continued to do work for places like Popular Mechanics until he retired some time in the 1990s, and he also did some fine art.

|

| (Covers by Harry Borgman and Ed Valigursky) |

William Barton has become fairly well known in recent years for a number of reputedly extremely dark and cynical novels, featuring lots of violence and lots of sex (sometimes rather icky sex). He often writes in collaboration with Michael Capobianco. I myself have not read any of his novels, but I have read a number of novellas in places like Asimov's and Sci Fiction, and the novellas are indeed often extremely dark and cynical, and they tend to feature plenty of violence and (sometimes icky) sex. They are also often very good -- in particular I like his two most recent Asimov's novellas: last year's "The Engine of Desire" and this year's "Off on a Starship".

Hunting on Kunderer has some sex, though it's not very icky (a bit maybe), and some violence. It's not what I'd call dark, but it is rather cynical. It's really not very good, though, not even close to as good as his later work -- the writing is at best routine, at worst clumsy, the plotting is perfunctory, the setting a bit ordinary.

Kunderer is a planet apparently consisting largely of jungles, with huge trees, and with a dominant predator much resembling a tyrannosaur. A small group arrives on the starship Wandervogel to take a hunting trip. These include Scott MacLeod, a space navy officer on leave; Uri Baruch, a 300 year old Jewish man who has just been ousted as long-time first minister of the Vinzeth Empire, and who has had his sexual organs restored to him after nearly 300 years as a eunuch; Pashai anke Soring, an alien who has been studying human sexuality; and Maryam, a whore who has been assisting Soring in his researches.

On arrival the four go off into the jungle with a guide named of all things Gilgamesh. Meanwhile, the starship has been sabotaged, and apparently only good luck got them safely to Kunderer. The captain quickly decides that one of the four passengers committed the sabotage, and he engages another guide and follows them in order to interrogate each suspect.

The action consists of a bit of hunting of the tyrannosaurs, a bit of ineffectually questioning by the Captain, a rather more effective investigation by the people repairing the starship, and other niceties such as the alien Soring trying to get Maryam to be seduced by or seduce other passengers in order to advance his scientific studies. There are a few deaths, a solution of sorts to the sabotage mystery, and a curiously upbeat (one might almost say, pasted on) ending.

I can detect traces of the future Barton in this book, but for the most part there is no indication that he would become the writer he did. A weak effort, with a couple of minor interesting touches but mostly not -- forgettable, on the whole.

In 1961 John T. Phillifent published a story called "The Stainless-Steel Knight" in If, under the "John Rackham" name. That story is the first part of the novel Life With Lancelot, which is padded out with two more stories of similar length. As far as I can tell, the two additional stories were not published elsewhere. In this book the three stories are called "Stainless Knight", "Logical Knight", and "Arabian Knight".

All three stories are set on a "Vivarian" planet, consisting of three continents, each a reserve for people living in imitation of a certain historical period. The hero is Lancelot Lake, who is given a back story in which he, a lowly spaceship technician, attempts to save a doomed spaceship, and fails, crashlanding on an alien world. He is posthumously awarded promotion to Prime G, the highest rank in Galactopol. Unfortunately for Galactopol, the aliens have super medical powers, and great interest in humans, and they save Lancelot's life, and give him extra physical strength and an alien companion, called the Shogleet. They can't do much for his brains, though.

Lancelot demands assignments worthy of his position, and as each continent is becoming destabilized -- failing to maintain their historical culture -- he goes to each one in turn. The first is a medieval culture, menaced by the appearance of a "dragon", and Lancelot must vanquish the knight who found the dragon, and then destroy the dragon (which is actually something else, as the reader readily guesses). This he does with the considerable help of the Shogleet, at the same time enjoying himself with several wives and a beautiful maiden who falls in love with him. The second is an Ancient Greek culture which has rejected the Gods, and Lancelot's job is to go down disguised as Apollo, and perform a few miracles to rekindle faith. But he and his lovestruck female technician companion end up in trouble, and the Shogleet must come up with another solution, inspired by a famous Greek comedy. The third culture is Arabian, and it is menaced by a renegade Galactic who is using the high-tech androids, afreets, and so on to rule a fictional Baghdad. Lancelot and a beautiful but sexually repressed fellow agent visit Baghdad disguised as Iskander and the Queen of Sheba, hoping to use the woman agent's charms to distract the bad guy. Unfortunately, the rat doses her with an aphrodisiac. Naturally, Lancelot ends up benefiting from her sudden compulsion for sex, while the Shogleet (with it must be said Lancelot's considerable assistance) again saves the day.

All in all, these are pretty weak stories. The core ideas are hackneyed, and Phillifent does very little new with them. The sex is a bit embarrassing -- the first story has only hints of it, but the later two, presumably written much later, both feature repressed women who fall for the alien-enhanced Lancelot, and who spend most of the story buck naked, and much of it begging for his attention. The plots are rudimentary, solved mainly by the Shogleet's conveniently scaled powers. Lancelot's character shifts a lot, too -- the basic setup is that he is a nebbish, more or less, stupid and way out of his depth and not much physically either. But by the last stories he has become somehow quite a bit more intelligent, and he seems to be rather more a physical specimen (even discounting the alien mods) than originally described.

I'm also a bit puzzled by the use of the Phillifent name. The original story was published as by "John Rackham", and "Rackham" was the name he used for all of his other Ace Doubles save one, and that one, Hierarchies, was originally an Analog serial as by "Phillifent" (which name he generally used only for his Analog stories (and some Man From Uncle tie-ins).)

Thursday, September 27, 2018

Old Bestseller Review: The Bright Face of Danger, by Robert Nielson Stephens

Old Bestseller Review: The Bright Face of Danger, by Robert Nielson Stephens

a review by Rich Horton

Back to a true Old Bestseller, though not a top bestseller. But certainly of that ilk.

Robert Nielson Stephens (1867-1906) was a journalist, theatrical agent, playwright and novelist, originally from Pennsylvania, later in New York, and then England, where he died before his 40th birthday. (He had long been ill.) He was a fairly popular writer in his time, and his best known work was a play, a novel, and later a movie, An Enemy to the King (1896). The book at hand, The Bright Face of Danger (1904), is a distant sequel to An Enemy to the King, concerning the son of the hero and heroine of that novel. My edition appears possibly to be a first, from L. C. Page, though it's inscribed "Paul Johnson, Salem Ill, from Tommy. Dec. 25, 1913", which suggests it was a Christmas present in that year. It's in fair to poor condition. It is illustrated by H. C. Edwards.

I have noticed that my reading of historical novels written around the turn of the 20th Century has included a number of novels about 16th and 17th Century France. Here's a summary (note that When Knighthood Was in Flower is primarily about England, with a short segment in France, but an historically significant segment):

1515: When Knighthood Was In Flower, Louis XII

1530: Under the Rose, Francis I

1593: The Helmet of Navarre, Henry IV

1608: The Bright Face of Danger, Henry IV

1630: Under the Red Robe, Louis XIII

(Each title is a link to my review of the novel in question. I should add that An Enemy to the King (which I haven't read) is set in about 1588, during the time of the Three Henries (Henry III, Henry IV, and Henry I of Guise).)

The novel itself is only peripherally about historical matters (and, oddly, one could argue that the faction of the bad guy in the book ends up winning, as Henry IV was assassinated in 1610). It opens with Henri de Launay, a rather bookish young man, deciding that he must set out to Paris to prove his courage and maturity, partly because his bookish ways sometimes excite comment in his fellows, partly because of his admiration for his father, the Sieur de Tournoire, and partly because the girl he fancies he loves has mocked his mustaches as negligible in comparison to one Brignan de Brignan. So he sets out on his way, with his father's somewhat hesitant approval, accompanied by one servant and with some advice from his father's old retainer.

The novel itself is only peripherally about historical matters (and, oddly, one could argue that the faction of the bad guy in the book ends up winning, as Henry IV was assassinated in 1610). It opens with Henri de Launay, a rather bookish young man, deciding that he must set out to Paris to prove his courage and maturity, partly because his bookish ways sometimes excite comment in his fellows, partly because of his admiration for his father, the Sieur de Tournoire, and partly because the girl he fancies he loves has mocked his mustaches as negligible in comparison to one Brignan de Brignan. So he sets out on his way, with his father's somewhat hesitant approval, accompanied by one servant and with some advice from his father's old retainer.

But at his very first stop, he meets another young man, a bit of an annoying braggart, and the two come to words, and then to a duel. Henri wins (naturally, or we wouldn't have much of a book!) and on the person of the dead man discovers a letter -- a plea for help from a woman who says "come at once, my life and honour depend on you". Henri decides he must try to find this lady and offer what help he can, so he sends his servant home to beg his father to negotiate a pardon for him (for the dueling death) from the King, and Henri sets on alone.

But at his very first stop, he meets another young man, a bit of an annoying braggart, and the two come to words, and then to a duel. Henri wins (naturally, or we wouldn't have much of a book!) and on the person of the dead man discovers a letter -- a plea for help from a woman who says "come at once, my life and honour depend on you". Henri decides he must try to find this lady and offer what help he can, so he sends his servant home to beg his father to negotiate a pardon for him (for the dueling death) from the King, and Henri sets on alone.

He manages, partly by happenstance, to discover who and where the lady in question is. She is the young wife of an old man, the Count de Lavardin. It seems the Count is insanely jealous of his wife (whom he married from a convent), and he must have decided that she had cuckolded him with the man Henri has killed. Fortuitously, Henri meets another man trying to get into the Chateua de Lavardin, and the two arrange a scheme: the Count is known to be a chess fanatic. They will masquerade as chess players, hoping to get an invitation to the Chateau.

Of course this all works. Henri's new friend is the better chess player, and he manages to beat the Count. Meanwhile, Henri wanders the Chateau, and ends up meeting the Count's beautiful wife, and her resourceful maid, Mathilde. It is quickly clear that the Countess, a devout Catholic (Henri is a Huguenot), is completely faithful to her husband, not because she loves him (he is rather a monster), but because of her marriage vows. But as the man Henri killed is not available to clear her name, she is likely to be severely punished. And indeed Henri will likely engender further jealousy from her husband, especially as his evil boon companion, the Captain de Ferragant, seems insistent on fostering such feelings in the Count. (De Ferragant either has designs of his own on the Countess, or perhaps he is himself jealous of her.)

So we can see where this is going. Henri of course is smitten with the Countess, who returns his feelings but will not betray her vows. This does Henri no good, as he is soon imprisoned by the Count, and threatened with death. Henri manages to discover evidence that the Count is plotting against the King (which explains the mission of his erstwhile chessplaying friend, who has disappeared). The magnificent Mathilde, and her local boyfriend, offer some daring help to allow Henri to escape -- but when the Countess is imprisoned herself, he must try to rescue her. And soon he is recaptured, and about to be executed ... when a sort of deus ex machina (though not really -- it is reasonably well explained) saves the day.

It's fun stuff, light of course, implausible, but I liked it. It must be said that the Countess comes off as a bit of a milquetoast -- her maid Mathilde seems the better woman! Indeed, Henri, while certainly proving his bravery -- kind of messes things up himself. Though he does end up with the mustaches of Brignan de Brignan!

a review by Rich Horton