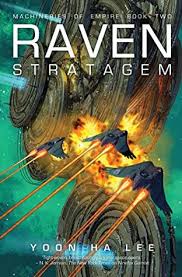

Raven Stratagem, by Yoon Ha Lee (Orbit, 978-0-316-38867-2,

$26, hc, 439 pages) September 2017

a review by Rich Horton

|

| (Cover by Chris Moore) |

I was very impressed

by Yoon Ha Lee’s first novel, Ninefox

Gambit, which made both the Hugo and Nebula shortlists last year. Raven Stratagem is the sequel (one more

book, Revenant Gun, is due in June

to complete the Machineries of Empire Trilogy, and there have been numerous

short stories set in the same universe, including “Extracurricular Activities”,

which will appear in my upcoming Best of the Year volume.) One thing to note

about these books is that they succeed quite well in being standalone in the

sense that each of the first two books reaches a satisfactory conclusion. (That

is not to say that I recommend reading Raven

Stratagem without having read Ninefox

Gambit, though I think one could without too much trouble.)

As the book open, General Kel Khiruev and her swarm of

warships have been tapped to deal with the heretical Hafn uprising. However,

she is waiting for an unexpected new Captain, Kel Cheris, for reasons obscure

to her. When Cheris comes on board, they suddenly realize that she has been

possessed by the undead General Shuos Jedao, who has been kept in the “Black

Cradle” for 400 years, after he massacred millions (including his own crew) at

the Battle of Hellspin Station. Jedao is a tactical genius, and the Hexarchate’s

military faction, the Kel, release him to be “anchored” to another Kel every so

often to make use of his ability. He and Kel Cheris (his anchor) just dealt with

the Hafn heretics at the Fortress of Scattered Needles. All this backstory is

the subject of Ninefox Gambit.

As Jedao outranks Khiruev, he takes over the swarm from her,

and the Kel crew are helpless to resist because of “formation instinct”. It

soon become clear that he has rebelled against the Hexarchate, but the

formation instinct prevents the crew from opposing him, though Khiruev barely

manages an assassination attempt. Jedao’s immediate mission, however, seems to be just

what Khiruev had been ordered to do – defeat the Hafn. And soon he is mentoring

Khiruev in some sense, and indeed bringing Khiruev to understand why he is

rebelling.

There are two more threads. One concerns Colonel Kel Brezan,

who is a “crashhawk” – immune to formation instinct. He could resist Jedao, so

Jedao had him expelled from the swarm (but not killed, key to Jedao’s ethic).

Brezan, desperate to prove his loyalty, jumps through hoops to get the message

about Jedao’s takeover to Kel Command – and eventually is charged with

accompanying an assassin who will kill Jedao, with now General Brezan taking

command of the swarm.

The other thread follows the Hexarch of the Shuos faction,

Mikodez, who seems to be the most powerful of the six Hexarchs, and who is coordinating

the reaction to Jedao’s insurrection. But Mikodez has some secret plans of his

own … This thread also involves his brother/double/lover Intradez, and his aide

Zehun, who has a history with Brezan, and a plan to make all the Hexarchs

immortal (one already is, but in an unsatisfactory fashion).

The novel is interesting reading throughout, with plenty of

action (and some pretty cool battle scenes), some rather ghastly (in a good

sense) comic bits, and lots of pain and angst. There is a continuing revelation

of just how awful the Hexarchate is, with the only defense offered even by its

supporters being “anything else would be worse”. There is genocide, lots of

murders, lots of collateral damage. The resolution is well-planned and integral

to the nature of this universe, with a good twist or two to boot. It’s a good

strong novel that I enjoyed a lot.

That said (those “buts” again!), Raven Stratagem didn’t make quite the impact on me that Ninefox Gambit did. Some of that could

be middle book syndrome, but not so much, really – as I said before, these two

books do a good job avoiding the structural issues, and semi-cheats, that

sometimes pop up with trilogies. I suppose I found some of the battle scenes,

and some of the star travel in general, a bit too, well, easy, as, too, some of

the characters’ personal convictions seemed to change a bit quickly. These are not

major problems, but I think they are reasons I consider it not quite as good as

the first book (which had the usual first book advantage of introducing a lot

of cool stuff). I am certainly looking forward to the conclusion, and there are

indeed mysteries and loose ends enough to be resolved.

I won’t know where it ranks on my Hugo ballot until I finish

reading the nominees, but of the four I’ve read, I do think I’d put it first.

But I don’t consider it as good as the five novels I nominated for the Hugo (though

actually the final two on my Hugo nomination list and Raven Stratagem are about the same quality in my mind – at the

level where we have to acknowledge that these are different books trying to do

different things, each succeeding pretty well in their own ways.)

One final amusing note – Khiruev’s swarm is called the

Swanknot, referring, I assume, to swans with their necks intertwined (or

knotted) – her emblem. But I couldn’t help thinking of it as “Swank not” –

meaning perhaps that the swarm isn’t too luxuriously appointed.