a review by Rich Horton

E. C. Tubb would have been 99 today, so I am reposting this review of one of his Ace Double appearances in his honor.

Tubb was a British writer, born 1919, died in 2010. He published something over 100 SF novels, and about as many short stories, under his own name and a variety of pseudonyms. One pseudonym was the memorable "Volsted Gridban"! His best known pseudonym was probably "Gregory Kern", under which name he wrote the "Cap Kennedy" books for DAW in the early 70s. (I have not read any of that series.) But he is by far better known for his long series of novels about Earl Dumarest and his search for his lost home planet, Earth. These were published first by Ace, then by DAW, from 1967 through 1985, with a final book showing up only in 1997 from a small press (apparently having been published sometime earlier in France, and presumably having been rejected by DAW). This series runs to 32 books, of which I have read 25 or so. They constitute a rather guilty pleasure -- very formulaic, very repetitive, sometimes downright silly, certainly not particularly good. But I found them enjoyable mind candy.

|

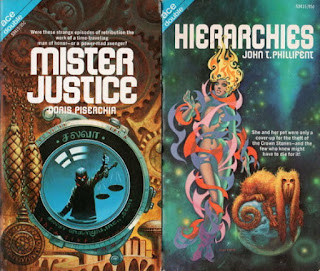

| (Cover by Kelly Freas) |

In the book just before The Jester at Scar, Kalin (one of the best and most important of the series), Earl came into possession of an incredibly valuable red ring, which gives the owner the ability to exchange minds with another person, and which the Cyclan covet. Thus he is now hunted by the Cyclan. As this book opens, Earl is staying on the spore-ridden planet Scar, with a poor woman. A couple of thugs invade her home, and after Earl is forced to kill them he notices that they have several other red rings. It seems clear that someone has hired people to try to retrieve red rings from anyone they can.

At the same time Jocelyn, the newly married ruler of the planet Jest shows up at Scar, along with his new adviser, a Cyber. Jocelyn hopes to find some profitable trade for his impoverished planet, while the Cyber of course has a deeper game -- he's figured out somehow that Dumarest is on Scar. (Tubb rather subtly plays a little game here -- Jocelyn, the "Jester" of the title, believes in the power of Chance and Fate and he thinks he has come randomly to Scar -- but it turns out that all this was planned by the Cyclan.) There's a fair amount of somewhat pointless toing and froing, and of course a knife fight, before Dumarest and a partner head out into the wilderness of Scar during the brief planetary summer to claim a cache of valuable Golden Spore. The Cyclan are after him, of course, but so too, luckily, is Jocelyn. And of course Dumarest has his own luck, skill, and fanatic determination on his side. The book is much of a piece with most of the Dumarest novels, lacking only a temporary love interest for Dumarest, and I'd place it in the middle range of Tubb's books.

Donald A. Wollheim is justifiably known as an editor, and hardly remembered as a writer. His editorial work at Ace and then at his own imprint, DAW, is significant if often controversial. On the one hand such things as his role in the pirated Ace editions of The Lord of the Rings, and his promotion of lots of low grade SF with famously crummy titles and tiny advances must be disparaged. On the other hand he was responsible for publishing early work by an astounding array of important writers such as Samuel R. Delany, Ursula K. Le Guin, and C. J. Cherryh. He also was editor (or co-editor) for two of the more significant Best of the Year collections.

He wrote a fair amount of unmemorable short fiction starting in 1934, most of it in the 40s. He also wrote quite a few juveniles in the 50s and 60s, under his own name, perhaps most notably the Mike Mars series. All his few adult novels seem to be as "David Grinnell". (The Ace Doubles under his own name were anthologies.) To Venus! To Venus! is the last, and close to his last piece of fiction.

To Venus! To Venus! is set in the fairly near future of the book's publication date, 1970 -- perhaps around 1990? A Russian unmanned probe has reached Venus and reports surprisingly balmy conditions -- nice enough for human habitation, even. The Americans are astonished -- all scientific evidence indicates that it is a hellhole, and they quickly put together a three man mission to land on Venus and settle the question once and for all. The Russians have also mounted a manned mission, and the two ships find themselves in a race.

|

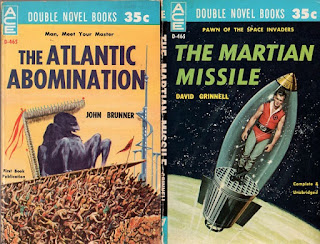

| (Cover by John Schoenherr) |

The American team consists of a straight arrow commander named Chet, and two contrasting subordinated -- a gungho guy named Quincy, and a cynical guy named Carter. Much is made, unconvincingly, of Chet's leadership skills in making them a team. At any rate, they reach Venus, but have difficulty landing in what turns out to be a hellhole as the scientists predict, and they seem to be stranded. It turns out that the Russians have also landed, almost simultaneously, and they still claim it's a balmy near paradise. But they too are in trouble. The only hope for either group is for the Americans to hike across the surface of Venus, more or less by dead reckoning, fortunately only 100 miles, to where they believe the Russian ship has landed. (As presented this is basically impossible, and to be fair it seems Wollheim knows this, and gives a fair account of the likely difficulties and doesn't deny that the ultimate success is due to pure luck.)

It's not really very good. Stiff dialogue, strained science, flat characters. It's all very earnest, both in the worshipful presentation of U.S. can-do engineering spirit, and in the ultimate message of Soviet/U.S. cooperation (a bit undermined perhaps by the cartoonish presentation of the only actual Russian character).