Ace Double Reviews, 24:

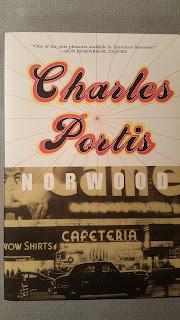

The Sun Saboteurs, by Damon Knight/

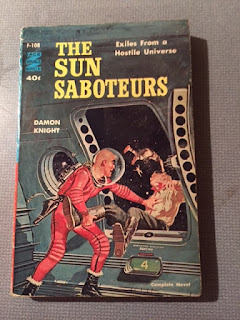

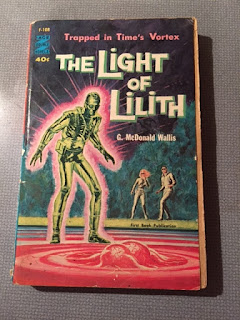

The Light of Lilith, by G. McDonald Wallis (#F-108, 1961, $0.40)

I decided to revise this post, and add a post on another old Damon Knight Ace Double, in part because Damon Knight's name came up recently in conversation, and it was suggested that Knight was a great writer of short fiction, but never figured out novels. I disagree -- I think Knight's late novels (most notably

Why Do Birds? and

Humpty Dumpty: An Oval) are exceptional. But in reality, his earlier novels are not nearly as good as his early short fiction. What is noticeable, however, is that he wrote a number of truly brilliant novellas, a few of which he expanded to short novel length. Arguably the best of these novellas -- one of the great novellas in SF history -- is "The Earth Quarter", which, expanded, became

The Sun Saboteurs.

Knight (1922-2002) of course is one of the great figures in SF history, a Grand Master. He might have been named Grand Master solely for his critical work (some collected in the seminal book

In Search of Wonder), and his editorial work (most notably the

Orbit series of original anthologies), and indeed also his organizational work (founder of the Milford writer's conferences as well as the chief driving figure behind the formation of the Science Fiction Writers of America (and their first president). But he was was a first rate writer as well, with such stories as "The Handler", "The Country of the Kind", "Masks", "Stranger Station", "Four in One", "I See You", "A for Anything", and "Fortyday" serving as highlights besides those I've already mentioned. (And that's not even bringing up joke stories like "To Serve Man", "Eripmav", "Cabin Boy", and "Not With a Bang".)

The Sun Saboteurs was the second of four Ace Double halves by Knight (three separate books). The original novella, "The Earth Quarter", appeared in

If in 1955. The book version is about 37,000 words long (the magazine version was less than half that length).

G. (for Geraldine) McDonald Wallis is almost unknown in the SF field -- this novel and her 1963 Ace Double half

Legend of Lost Earth are her only in-genre publications. However, she had an extensive career under the name "Hope Campbell". In the 1940s she published a number of stories in romance magazines, with titles like "Marriage of Inconvenience" and "Forbidden Female"*. Then from the late 60s into the 80s she published, also as by Campbell, a number of middle-grade and YA novels, such as

Peter's Angel (aka

The Monsters' Room),

Mystery at Fire Island, and

Why Not Join the Giraffes?. (There was also apparently a YA-marketed edition of

Legend of Lost Earth under the "Hope Campbell" name.) She was born in 1925 -- thus her first story (that I know of), published in the January 1943

All-Story Love magazine, appeared when she was only 17. She was raised, according to the front matter of

The Light of Lilith, in Hawaii and the Orient, and she had a career as an actress. As far as I know she is still alive.

The Light of Lilith is about 45,000 words long.

(*It is just possible that the 1940s romance stories were by a different "Hope Campbell".)

I don't really think that Don Wollheim (or whoever else selected Ace Double pairings) necessarily chose stories that were thematically or otherwise related, but every so often it happened. This is a particularly striking case. Both

The Sun Saboteurs and

The Light of Lilith share a strikingly anti-Campbellian theme. In both, humans are presented as evil warmongers amid a generally peaceful Galaxy. In both, humans are forced to accept their inferiority to many alien species, and in both, many or most humans simply fail to do so. In both, humans are faced with isolation in the Solar System, and eventually with extinction. That said, one novel is far better than the other.

Probably to no one's surprise, the better of the two is

The Sun Saboteurs. In this book a smallish colony of humans is confined to "the Earth Quarter" on the home planet of the insect-like Niori. Other similar enclaves are located on other alien planets, while humans on Earth itself have descended to barbarism amid the ruins of technological society. The viewpoint character is Laszlo Cudyk, 55 years old, a writer and jeweler, and one of the most respected citizens of the Earth Quarter. Other key characters are the mayor, Min Seu; the gang boss, Mr. Flynn; the Orthodox priest Astareo Exarkos; the mad old man Burgess, who believes that humans dominate the Galaxy, and his differently mad daughter Kathy, who keeps losing lovers to one fanaticism or another; and finally the evil Rack, who plots to rebel against the aliens, killing as many as he can.

The action is precipitated by the visit of one Harkway, from the Minority Peoples League, which works for accommodation with alien rule -- either by pushing for human equality on alien planets, or for alien help in restoring Earth. The MPL is bitterly opposed by the likes of Rack, who believe that aliens are inferior vermin, and that any truck with them is treason to humanity. The charismatic Rack controls a group of thugs, and one of them beats Harkway to death. This is a particular problem because the aliens cannot conceive of murder, and their sufferance of the Earth Quarter is predicated on human obedience to their laws. But Rack forces the issue by announcing that he has formed a navy, and will be taking the battle to the aliens, and that those humans who refuse to follow him are traitors too.

Cudyk observes this all, intervening in virtuous but ineffective ways when he can. But he is only a spectator when Rack's plans lead to truly incomprehensible evil actions. The final resolution turns on an ironically small action, perhaps Cudyk's though really almost anyone's.

The novel is very well written -- from the first it is clear we are in the hands of a real writer, even though this dates, especially in its first version, to quite early in Knight's career. (To me the contrast with the writing of the Wallis novel was particularly marked.) Cudyk is a very well depicted viewpoint character. The others are more types than fully rounded characters, but well-chosen and nicely portrayed. The action is mostly in a minor key, and the entire feel is both sad and bitterly cynical -- perhaps just a bit too much so -- humans aren't really this bad, and moreover I don't believe in aliens as "good", as sin-free, as those he shows us. There are some missteps -- the general SFnal background is only lightly sketched, and not awfully believable, but that doesn't matter that much. (I was particularly bothered that the action is apparently set in 1984, 20 years after the colonies were established on the various alien planets -- even in 1955 I don't think anyone could believe that men would have reached the stars, fought a barbaric interstellar war, and destroyed Earth by 1964.) The book's bitter argument against humanity is overstated and almost shrill over 37000 words -- I think it worked better in the novella -- but still it is worth reading. Knight later collected "The Earth Quarter" (in

Rule Golden and Other Stories), which might signal that he preferred the shorter version as well -- although I am not sure that version is not actually the expanded version under Knight's preferred title.

As for

The Light of Lilith, it is a pretty awful novel, one of the worst novels I've read in this Ace Double review series. As I mention, the theme is basically similar to the Knight novel, but with a bit more hope in the end. Not really a bad theme, but, unfortunately, a theme doesn't make a novel -- it helps to have believable characters, a consistent and entertaining plot, and interesting SFnal ideas. This book does OK on the first part, at least by the standards of the day in SF, but it fails ridiculously as to plot, and as to scientific ideas.

The hero is Russell Mason, a "reporter" for the Earth Federation. He has been trained from the age of 6 to be a spaceman, and his particular job is to visit human-colonized planets and report on conditions. He is coming to Lilith, an "experimental" planet. Experimental planets are unusual places, with no indigenous life (not counting plants or lower animals -- basically, no potentially intelligent life as I read it, though that's not what Wallis wrote), on which humans perform certain experiments, ostensibly into physical laws. Lilith itself is particularly interesting because, get this, it has colors not found in the normal electromagnetic spectrum. Oh.

When Mason arrives, he finds the spaceport deserted, and feels himself gripped by a terrible fear. He stumbles across one survivor, who dies soon but after warning Mason -- "our fault". Mason manages to make his way to the remote lab, where the remaining humans have retreated. It seems their experiments have somehow caused changes in the light of Lilith, potentially very dangerous.

Mason allows himself to be exposed to a curious manifestation of the light, and he is transformed. He seems to travel in time, and he sees a vision of Man's future, a terrible vision that suggests that humans will be punished by the rest of the intelligent races in the galaxy. Is there something he can do to change things? Then he discovers what sort of research has really been going on on Lilith (weapons research, naturally), and he also discovers other secrets about Lilith and the experimental planets program that disgust him. He must try to obtain help from mysterious aliens, and persuade humans to give up their doomed experimental planet research.

The problem, basically, is a fairly random plot, a compendium of not well integrated incidents; and, worse, a whole bunch of just plain silly so-called scientific ideas, such as the "light" of Lilith. I really thought it a stupid book.

Just for fun, I'm going to append another review I did long ago of an Ace Double with Damon Knight contributing both halves:

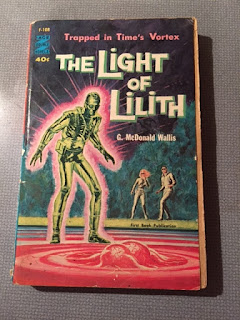

Ace Double Reviews, 4:

The Rithian Terror, by Damon Knight/

Off Center, by Damon Knight (#M-113, 1965, $0.45)

The Rithian Terror is a short novel (or novella), of about 36,000 words. It was originally published in

Startling Stories for January 1953 -- probably in a shorter version, but I will note that 36,000 words was by no means an unusual length for a story in

Startling.

The Rithian Terror was first called "Double Meaning" -- indeed, I believe the only time it appeared as "The Rithian Terror" was in this Ace Double.** It was later published as half of a Tor Double (under the title "Double Meaning") and backed with another Knight short novel, "Rule Golden"). As far as I can tell, the only other stories to be both Ace Double halves and Tor Double halves are two by Jack Vance: "The Last Castle" and "The Dragon Masters"; and two by Leigh Brackett: "The Sword of Rhiannon" and "The Nemesis from Terra". (Norman Spinrad's "Riding the Torch" was both a Tor Double and a Dell Binary Star half.)

Off Center is a story collection, with 5 stories, totalling about 44,000 words. It should not be confused with the UK collection

Off Centre, which consists of the contents of

Off Center plus "Masks", "Dulcie and Decorum", and "To Be Continued".

As it happens, both

The Rithian Terror and its erstwhile Tor Double companion, "Rule Golden", featured superior (both morally and physically) aliens coming to Earth. I liked

The Rithian Terror a fair bit. It features a far future (said to be 2521, felt like 2050 at most) Earth-based Empire, which has a policy of crushing alien races which it encounters. The latest are the Rithians, and after some years of covert harassment by Earth, the Rithians have snuck a spy team onto Earth itself. The story is told from the point of view of the Security man who leads the effort to find the last remaining Rithian, and the points of interest are his relationship with an "uncivilized" member of a breakaway human planet which has good dealings with Rithians, and his courtship of an upper-class woman. Again, the story is fast-moving and enjoyable, with a sound moral point, and the resolution of the main action is nicely calculated, though there is an unconvincing character change pasted on.

The stories in

Off Center are:

"What Rough Beast" (10,800 words, from the February 1959

F&SF) -- a man has the power to change the past (involving reaching into parallel universes), thus preventing bad things from happening. Is this a good thing?

"The Second-Class Citizen" (2800 words, from

If, November 1963) -- a man who teaches dolphins tricks escapes underwater when the holocaust comes.

"By My Guest" (24,500 words, from

Fantastic Universe, September 1958) -- a man drinks a mysterious vitamin and suddenly he can "hear" the ghosts that possess him. This story read to me as if it were Knight trying to do Sturgeon. I liked it, though the ending wasn't quite up to the buildup.

"God's Nose" (800 words, from the men's magazine

Rogue in 1964) -- not really SF, a meditation on what God's nose would be like, with, perhaps, a cute but naughty punchline.

"Catch That Martian" (5000 words, from the March 1952

Galaxy) -- there is an epidemic of people being shifted to another dimension, and a policeman theorizes that the cause is a visiting Martian who punishes rude or annoying people in this fashion.

All in all, a very solid brief story collection. "What Rough Beast" is particularly strong, and moving.

(**Remember, it was said of Don Wollheim that if the Bible was published as an Ace Double he'd change the titles of the Old and New Testaments to

War God of Israel/

The Thing With Three Souls.)

Ace Doubles have a fairly declassé image. One doesn't tend to look

for all time classics or Hugo candidates among them. Though as previous

reviews in this series have shown, there were first rate novels and

novellas published as Ace Double halves, such as Jack Vance's Hugo

winner "The Dragon Masters". (That was, however, a reprint.) But even

so, seeing that Ursula K. Le Guin's first novel was an Ace Double came as a mild surprise to me, some time back when I encountered this pairing. Since then I've realized that that wasn't really that rare, for example, Samuel R. Delany also had early novels published as Ace Doubles, as did many other great writers.

Ace Doubles have a fairly declassé image. One doesn't tend to look

for all time classics or Hugo candidates among them. Though as previous

reviews in this series have shown, there were first rate novels and

novellas published as Ace Double halves, such as Jack Vance's Hugo

winner "The Dragon Masters". (That was, however, a reprint.) But even

so, seeing that Ursula K. Le Guin's first novel was an Ace Double came as a mild surprise to me, some time back when I encountered this pairing. Since then I've realized that that wasn't really that rare, for example, Samuel R. Delany also had early novels published as Ace Doubles, as did many other great writers.