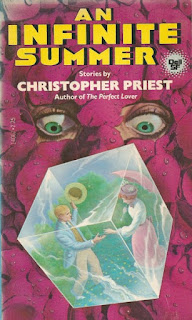

Review: An Infinite Summer, by Christopher Priest

by Rich Horton

To repeat myself: The late Christopher Priest (1943-2024) was one of the greatest SF writers of his generation. He made an early splash with novels like Inverted World and A Dream of Wessex (aka The Perfect Lover), followed by The Prestige, which was made into a successful movie by Christopher Nolan, and then by any number of stories and novels in his Dream Archipelago sequence. I wrote an obituary of him for Black Gate here.This is the last, for now, of my reviews of Christopher Priest's work, sparked by being on a panel about his fiction at Readercon this year. (Though I hope to get around to reading The Affirmation, and rereading A Dream of Wessex, Inverted World, and The Islanders, some time in the next few months.)

An Infinite Summer (1979) was Priest's second story collection, but his first significant one. It includes five stories:

"An Infinite Summer" (Andromeda 1 (1976), 8500 words)

"Whores" (New Dimensions 8 (1978), 5200 words)

"Palely Loitering", (F&SF, January 1979, 17800 words)

"The Negation" (Anticipations (1978), 11900 words)

"The Watched" (F&SF, April 1978, 20500 words)

Of these stories, three are definitely part of his extended Dream Archipelago sequence -- "Whores", "The Negation", and "The Watched". "An Infinite Summer" is often listed as a Dream Archipelago story as well, though I frankly don't see it. The stories are mostly longer, as you can see."An Infinite Summer" was written for Harlan Ellison's Last Dangerous Visions anthology. As Priest told it in his brilliant long essay on that non-book, The Last Deadloss Visions, Ellison asked him more than once for a submission. and finally Priest obliged. He sent the story to Ellison, and after several months, had not received a response. So he withdrew it -- which is a good thing. I will say that I don't think it's precisely a "dangerous" story, at least no more so than any outstanding piece. But it is outstanding, and the thought of it having potentially stayed in limbo for nearly 50 years is depressing.

"An Infinite Summer" tells of Thomas James Lloyd, who, when we meet him, is in London, the "town" of Richmond, during the Blitz. He lives alone, and does odd jobs, and we quickly learn that he can see invisible things -- strange people he calls "freezers", and what he calls "tableaux" -- three dimensional images of people suspended in a pose. Then back to 1903 -- Thomas is 21, of a wealthy family, and he is supposed to marry Charlotte Carrington -- but he is instead in love with her younger sister Sarah. And he arranges to spend a little time alone with Sarah one day, and learns that she too wishes to marry him, and then -- strange people approach and "freeze" them, as they are about to embrace. The upshot is: for unknown reasons Thomas became unfrozen some time in the '30s, but Sarah is still in the tableau, and he has stayed nearby, decades out of sync with his own time, in the hopes that she too might be unfrozen soon. The climax comes when a German bomber crashes in the area, attracting the attention of the "freezers" ... with a powerfully bittersweet ending for Thomas and Sarah. I have always found this story particularly affecting, and effectively weird. We never do learn the motives or origin of the "freexers", but of course the story isn't about them.

"Whores" is set in the Dream Archipelago. A soldier from the endless war between countries on the Northern Continent has been invalided out of the army, as an enemy weapon has given him sometimes crippling synaesthesia, and comes to an island where he had come before, for "recreation". He's obsessed with finding one particular girl he'd gone to before -- but the war has surged back and forth over this island (in later stories, the Archipelago maintains strict neutrality, but this one, one of the first to be written, speaks of a front having been opened in the Dream Archipelago.) The woman he wanted to find has been killed, but he ends up with another woman, and their encounters are weirdly altered by his synaesthesia, and perhaps by something else that the soldiers had been warned about -- and the story ends in psychological horror. It's short and quite dark, and strange in a distinctly Priestian way.

"Palely Loitering" is not a Dream Archipelago story. It is set in a far future in which Earth has voluntarily reverted to what seems 19th Century tech and social customs. Mykle is telling of events in his past, beginning in his childhood with a visit to Flux Channel Park, which had been built to aid the launch of a starship -- the only starship ever -- and as a result, has some strange spatio-temporal qualities. To wit, there three bridges over the Flux Channel -- the ordinary Today Bridge, plus the Tomorrow Bridge and the Yesterday Bridge, one of which takes you a year into the future, the other into the past. Each year his family goes on an excursion there, and they can go either into the future or into the past (naturally, returning to their time by going back over the opposite bridge.) This time, Mykle impulsively jumps off the Tomorrow bridge at an angle -- which it turns out takes him years farther into the future. At first he is panicked, but a young man comes to help him, and shows him how he can return to his time by jumping back at just the right place. But before Mykle returns, he sees, on the far side of the channel, a pretty girl -- a girl who the young man who has helped him seems to be obsessed with.

A few years later, the now teenaged Mykle yields to temptation and jumps to the future again -- and again sees the girl on the other side. Now he too becomes obsessed with Estyll (as she is named). One day he meets a young boy on the future side -- himself, of course, as the reader has already guessed. He begins to imagine himself and the girl as lovers ... but sees no way to make it happen. Then his father dies suddenly, and his life changes -- he must learn to take over his father's responsibilities (which are related to the flux channel), and he must make an appropriate marriage, which he does -- a happy one. And he mostly forgets about the girl. Until, decades in the future, the starship is returning, which will mean the Flux Channel Park must be cleared -- and Mykle remembers his youthful obsession, and wonders if he can learn any more about the mysterious Estyll ... It's a sweetly and ambiguously romantic story, with an oddly nostalgic atmosphere, and a somewhat open ending. One of Priest's better stories, I think, and more sentimental than he usually was.

"The Negation" is set on the world of the Dream Archipelago, but on a continent. Dik is a young man, who has been conscripted into his country's Border Patrol, and has been sent to a border town, to patrol the wall on the border between his nation and their rival. He had been an aspiring poet, and was obsessed with a novel called The Affirmation, by Moylita Caine. And Caine is visiting this town. (Caine has been assigned a project by the authoritarian rulers of the country, to write a play.) Dik manages to get a pass to go and visit her, and they strike up a tentative sort of friendship -- Caine is pleased that he read her novel closely, and is happy to discuss it with him at length. But there are issues -- the leading "burgher" of this town, Clerk Tradayn, seems to want to coerce Caine into sex, and it's clear that Caine is an opponent of the regime. Eventually she is arrested -- and a short story she had written for Dik, called "The Negation", is taken as evidence. Dik comes to realize the short story must have been intended as a message to him -- but to do what? It's an involving story with a possibly hopeful, if ambiguous, ending. It's also, of course, interesting that Caine's novel was called The Affirmation, which became the title of Priest's well-regarded 1981 novel, his first Dream Archipelago novel. I haven't read the book, though I plan to soon -- I don't know if "The Negation", and Moylita Caine's novel, are directly related to Priest's novel (of course it's highly possible that Priest was already working on it in 1978 when "The Negation" was written.)

"The Watched" is set on the island of Tumo. Yvann Ordier is a man who has emigrated to the Dream Archipelago from the northern continent, after he made a fortune selling the miniature surveillance devices called scintillae. He has made himself a comfortable home, and has a beautiful lover. His home is very near the area on Tumo reserved for the Qataari, refugees who were forced to leave the southern continent when the warring countries from the north decided to move their active fighting to that continent. Ordier's lover Jenessa is an anthropologist who studies the Qataari, a very secretive people, who simply freeze when any outsider comes near them. The early chapters establish Ordier as something of a voyeur, obsessed with watching -- he watches his beautiful lover with lust, he obsessively tries to detect the scintillae that end up in his house (scintillae are so small they get everywhere.) And, importantly, he has found an odd old structure on his property with a difficult to reach vantage from which he can peer through a small fault in a stone wall at a sort of theater in the Qataari area. And here he watches a beautiful Qataari woman who seems to be practicing for a sort of ritual dance the Qataari do.

The story's evolutions involve a plot by one of Jenessa's fellow anthropologists to spy on the Qataari from the air, and the anthropologist's visit to Ordier's house, where he might find Ordier's secret vantage point, but mostly it concerns Ordier's growing obsession with the Qataari dance, and the young woman who is its centerpiece, and the clear sexual implications of the dance. As well as the supposedly narcotic Qataari roses ... The climax borders on horror, as Ordier feels he is being invited to participate in some sense in the Qataari ritual -- there are very creepy overtones throughout, and the result is disturbing and powerful.

This is a major collection. The bulk of the rest of Priest's career was devoted to novels, though he did continue to write some short fiction, much of it also set in the Dream Archipelago, but it would be fair to say, I think, that this is the Priest story collection to read first.