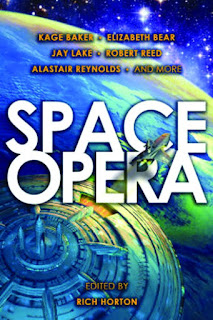

The following is the introduction to my 2014 anthology Space Opera, which collected outstanding 21st Century short fiction in the Space Opera subgenre.

Space Opera: Then and Now

by Rich Horton

The term space opera was coined by the late great writer/fan Wilson (Bob) Tucker in 1941, and at first was strictly pejorative. Tucker used the term, analogous to radio soap operas, for “hacky, grinding, stinking, outworn, spaceship yarn[s].” The term remained largely pejorative until at least the 1970s. Even so, much work that would now be called space opera was written and widely admired in that period . . . most obviously, perhaps, the work of writers like Edmond Hamilton and, of course, E. E. “Doc” Smith. To be sure, even as people admired Hamilton and Smith, they tended to do so with a bit of disparagement: these were perhaps fun, but they weren’t “serious.” They were classic examples of guilty pleasures. That said, stories by the likes of Poul Anderson, James Schmitz, James Blish, Jack Vance, Andre Norton, and Cordwainer Smith, among others, also fit the parameters of space opera and yet received wide praise.

It may have been Brian Aldiss who began the rehabilitation of the term with a series of anthologies in the mid 1970s: Space Opera (1974), Space Odysseys (1974), and Galactic Empires (two volumes, 1976). Aldiss, whose literary credentials were beyond reproach, celebrated pure quill space opera as “the good old stuff,” even resurrecting all but forgotten stories like Alfred Coppel’s “The Rebel of Valkyr" (1950), complete with barbarians transporting horses in spaceship holds. Before long writers and critics were defending space opera as a valid and vibrant form of SF. (Coppel, by the way, reimagined “The Rebel of Valkyr” much later as a series of very enjoyable young adult books, undeniably Space Opera, beginning with The Rebel of Rhada (1968), under the pseudonym Robert Cham Gilman.)

By the early 1990s there was talk of “the new space opera” at first largely a British phenomenon, exemplified by the work of Colin Greenland (such as Take Back Plenty) and Iain M. Banks (such as Use of Weapons) - both of those novels were first published in 1990. “The new space opera,” it seems to me, was essentially the old space opera, updated as much science fiction had been by 1990, with a greater attention to writing quality, and a greater likelihood of featuring women or people of color as major characters, and perhaps a greater likelihood of left-wing political viewpoints. Once one noted the existence of “the new space opera” it was easy to look back and see earlier examples, such as Melissa Scott’s Silence Leigh books (beginning with Five-Twelfths of Heaven (1985)), M. John Harrison’s cynical The Centauri Device (1974), and Samuel R. Delany’s Nova (1968). One might also adduce Earthblood (1966), by Keith Laumer and Rosel George Brown, which takes a somewhat more cynical view of its hero than most Space Opera up to that point.

[I need to acknowledge here an observation that Cora Buhlert made, and I thank her for it. I completely dropped the ball by failing to mention the important (and very popular) work in this "pre-New Space Opera" time frame of two essential writers, both Grand Masters: C. J. Cherryh and Lois McMaster Bujold. Much of Cherryh's work is certainly Space Opera, and an exceptional example of it. Lots of people will cite the Foreigner books, or the Union/Alliance books, but I confess an abiding fondness for some very early novels: Brothers of Earth (1976), Hunter of Worlds (1977), and the Faded Sun trilogy (1978-1979). About a decade after Cherryh began publishing, Lois McMaster Bujold's Barrayar books started appearing, beginning with Shards of Honor (1986). These are often called Military SF, and they do cross all sorts of subgenre boundaries (as books should!) but books about a space-based empire involving wars between planets surely fit the Space Opera mold. I feel sure that in addition to Delany, Scott, and Harrison the books of Cherryh and Bujold were part of the brew that "New Space Opera" writers were either extending or reacting to.]

Nova is my personal choice as the progenitor of space opera as a revitalized genre, but that’s probably a largely personal choice. (Nova is one of my favorite novels). Others could certainly point to something different: perhaps Barrington Bayley’s The Star Virus (1970 in book form, but a shorter version appeared in 1964). Even more sensibly one could say that space opera never went away—what about Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination (1956), to name just one seminal earlier work?

Perhaps, then, The Centauri Device is in retrospect the key work. Harrison conceived it explicitly as “anti-space opera,” and it was a reaction not just to the likes of Doc Smith, but to Nova, which Harrison had called “a waste of time and talent.” To quote Harrison himself, from his blog: “I never liked that book [The Centauri Device] much but at least it took the piss out of sf’s three main tenets: (1) The reader identification character always drives the action; (2) The universe is knowable; (3) the universe is anthropocentrically structured & its riches are an appropriate prize for people like us.”

I should note in this context that my suggestions that books like Nova and The Centauri Device were important to the development of "The New Space Opera", especially the British version of same, have been plausibly challenged by Ian Sales -- who certainly knows whereof he speaks. Sales suggest that both Nova and The Centauri Device were not widely available in the UK by the early 1990s, when books like Use of Weapons appeared, and suggests a closer link to "Radical Hard SF", as exemplified by British writers like Alastair Reynolds and Stephen Baxter (both of whom certainly have written Space Opera.)

Even if The Centauri Device verges on parody, and explicitly disapproves of its subgenre, those three principles do suggest an alternate path for space opera, perhaps a truer definition of the “new” space opera: less likely to be anthropocentric in approach, less likely to accept that the universe is knowable, less likely to have the main character succeed (even if he or she still does drive the action). And, anyway, Harrison returned to space opera with his remarkable recent trilogy, Light (2002), Nova Swing (2006) and Empty Space (2012). Those books certainly read like space opera to me, but they also certainly tick the boxes Harrison lists above. (Harrison also, less importantly perhaps, started a trend for clever ship names in The Centauri Device, using phrases from the Bible and Kipling for spaceships named Let Us Go Hence and The Melancholia that Transcends All Wit. That led, it would seem, to Iain M. Banks’ famous names for his Culture ships, and to similarly cute names in the work of many other writers.)

At any rate, once established as an essentially respectable branch of SF, space opera has continued to flourish. Some of it shows aspects of Harrison’s model, at least in parts, other stories are as triumphalist as anything that came before, more often we see a mix. A good recent example might be Tobias Buckell’s Xenowealth series, beginning with Crystal Rain (2006) - featuring heroes and heroines from nontraditional cultures, and somewhat ambiguous about the place of humans in a hostile universe, but also most assuredly featuring main characters with tons of agency and ability to drive the plot, and a general sense of cautious and perhaps conditional optimism.

The list of enjoyable space opera novels in recent years is long - notable practitioners include Alastair Reynolds, Karl Schroeder, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Nancy Kress, John Barnes, Elizabeth Moon, and James S. A. Corey; and I could go on for some time.

This book collects short fiction, however. One of the near defining characteristics of space opera is a wide screen, and this seems to drive longer works. It’s not nearly as easy to evoke the feeling of vastness, of extended action, that we love in space opera over a shorter length. But it can of course be done. Two of the best books of the past few years are original anthologies edited by Gardner Dozois and Jonathan Strahan: The New Space Opera, and The New Space Opera 2. These are packed with delicious stories, undeniable space opera of a variety of modes and moods, and they show that you don’t need five hundred pages for a good space opera. I’ve chosen a piece or two from each of these books for this volume.

I also must mention one newer writer in particular: the remarkable Yoon Ha Lee. He has yet to publish a novel [he has since, of course, with the outstanding Machineries of Empire books, certainly themselves very much space opera], but an array of striking stories has already established an impressive reputation. He has written work in multiple subgenres, but one of his continuing themes is war, and often war in space, between planets . . . which means, more or less, space opera. And in the briefest of spaces (see what I did there?) he can evoke a war extending across centuries and light years.

So, this book, which collects twenty-two outstanding stories, some traditional space opera in flavor, others which look at those themes from different directions; some set across interstellar spaces, others confined to the Solar System; some intimate character stories, other action packed; some (perhaps most) concerned with war and the effects of war, but others more interested in the grand spaces of the universe. But all, above all, fun.

[From the perspective of 2021, I will add, it's easy to see that just as I was writing (in mid-2013) we were beginning to witness a spectacular explosion of wonderful new space opera. Ann Leckie's Ancillary Justice appeared that year, and in 2016 came Yoon Ha Lee's Revenant Gun. Leckie won a Hugo for Ancillary Justice, and another excellent space opera, Arkady Martine's A Memory Called Empire (2019) also took that award. Add excellent recent work by Kameron Hurley, K. B. Wagers, Gareth Powell, Karen Lord, Aliette de Bodard, Tim Pratt, Linda Nagata, Elizabeth Bear, and many others, and it's clear we are in a great time for space opera.]